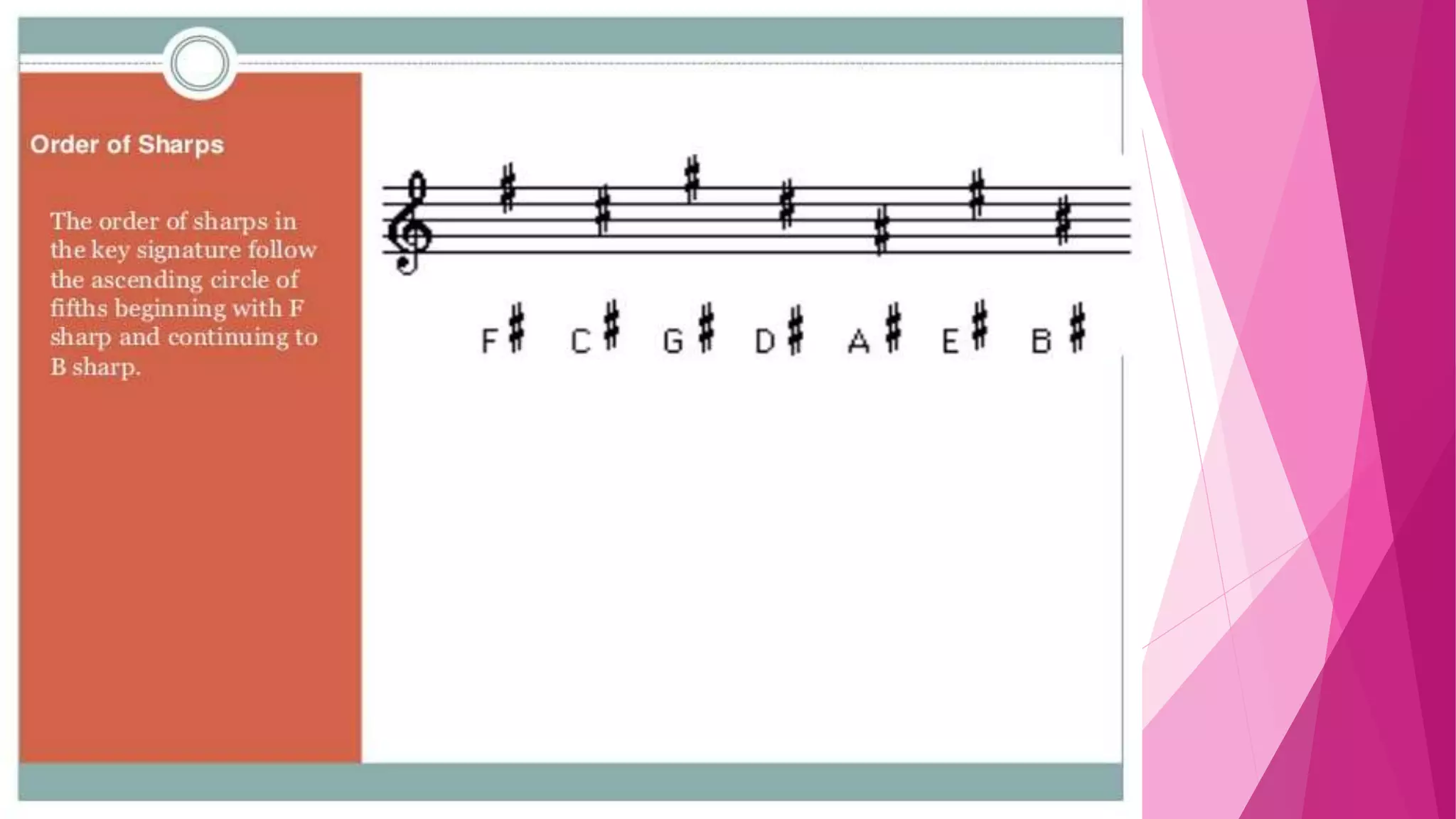

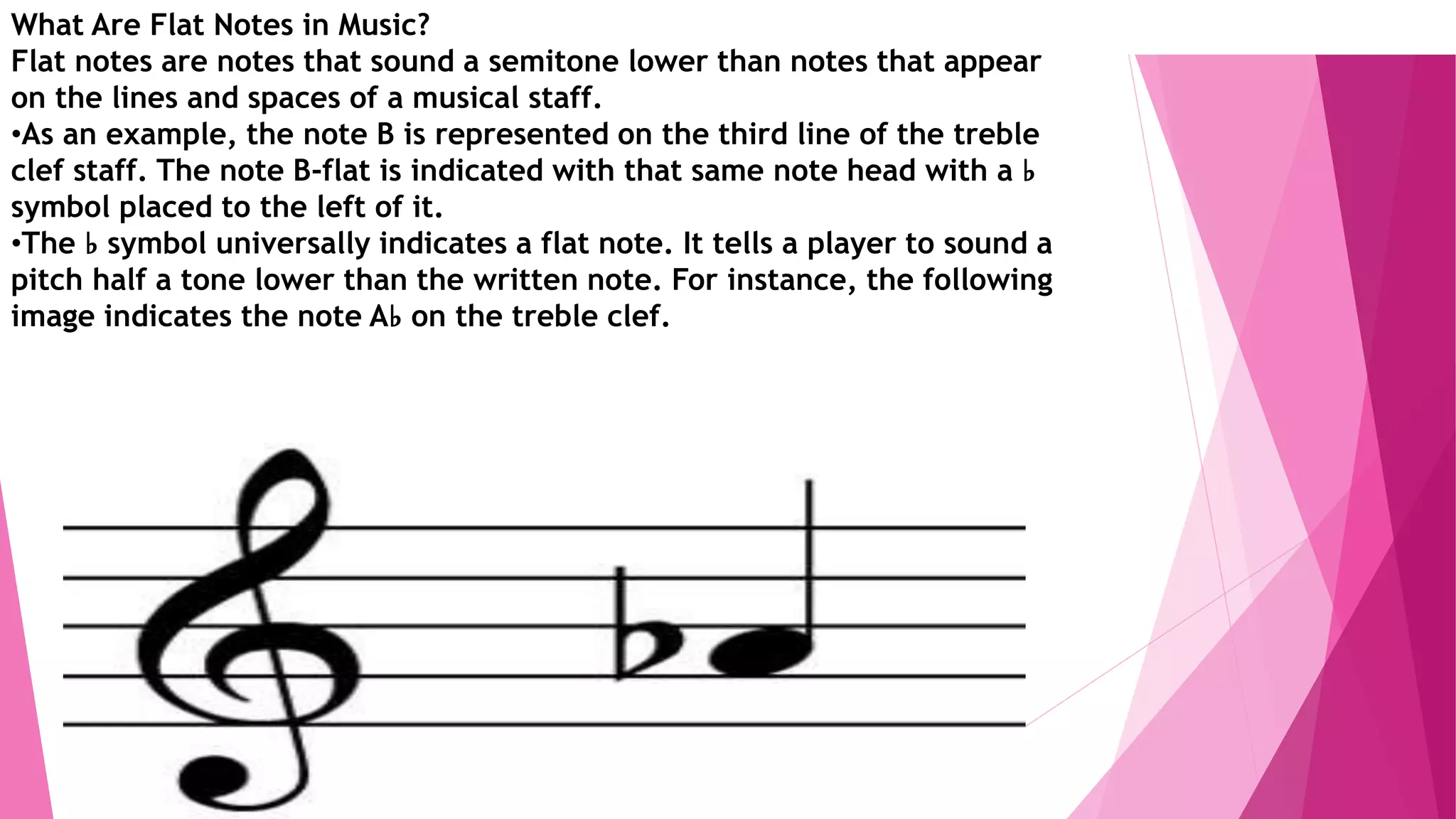

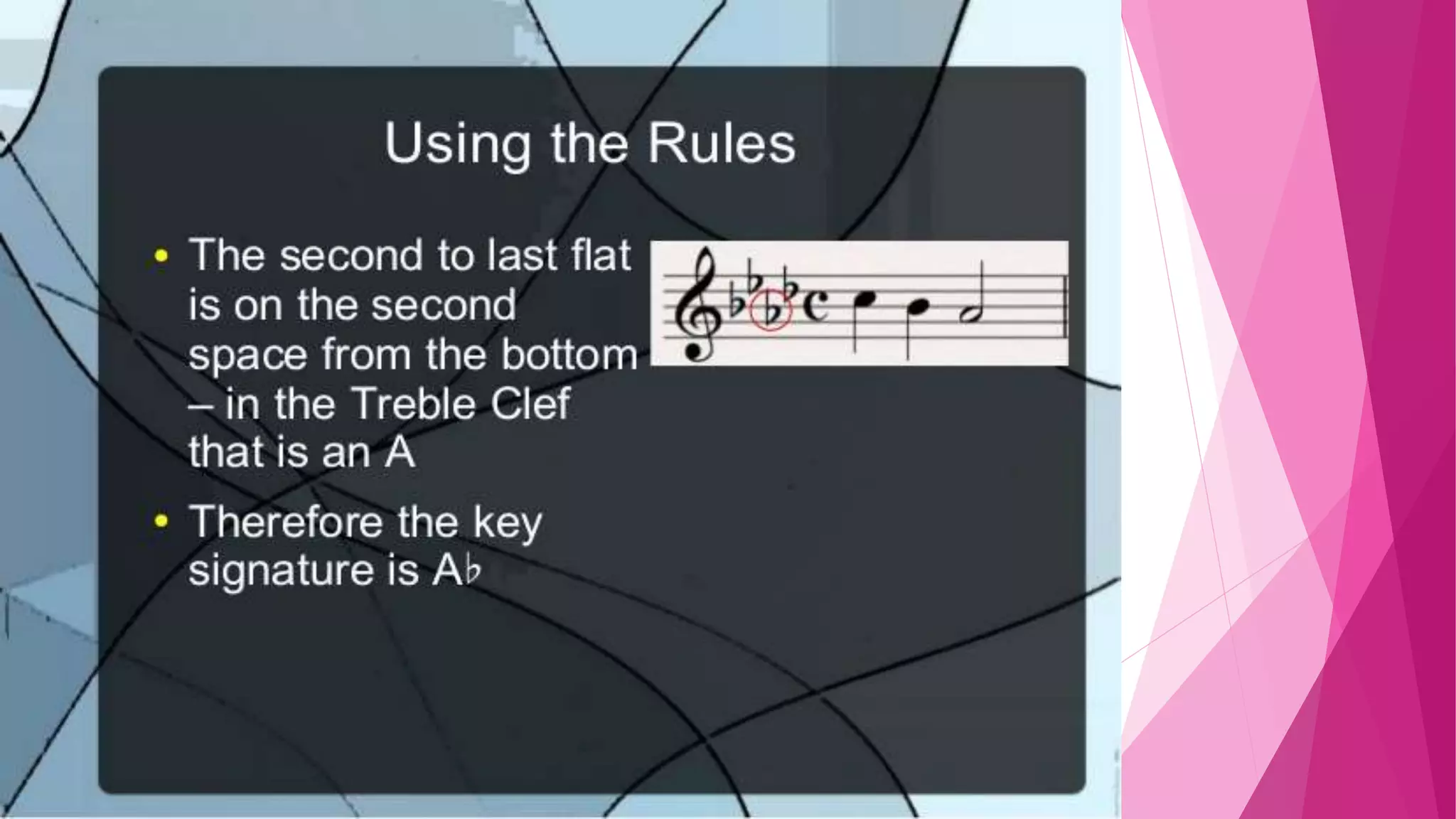

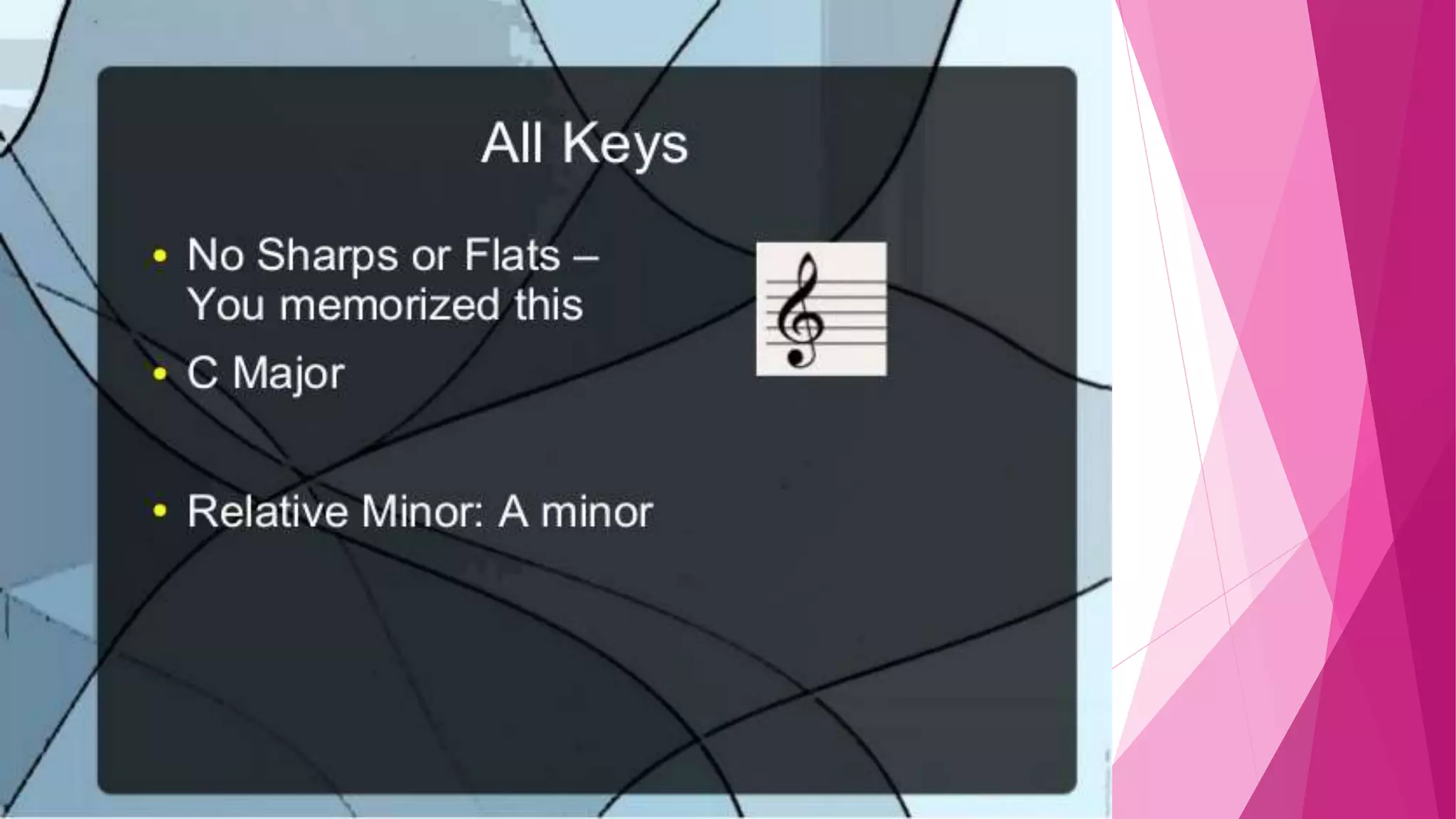

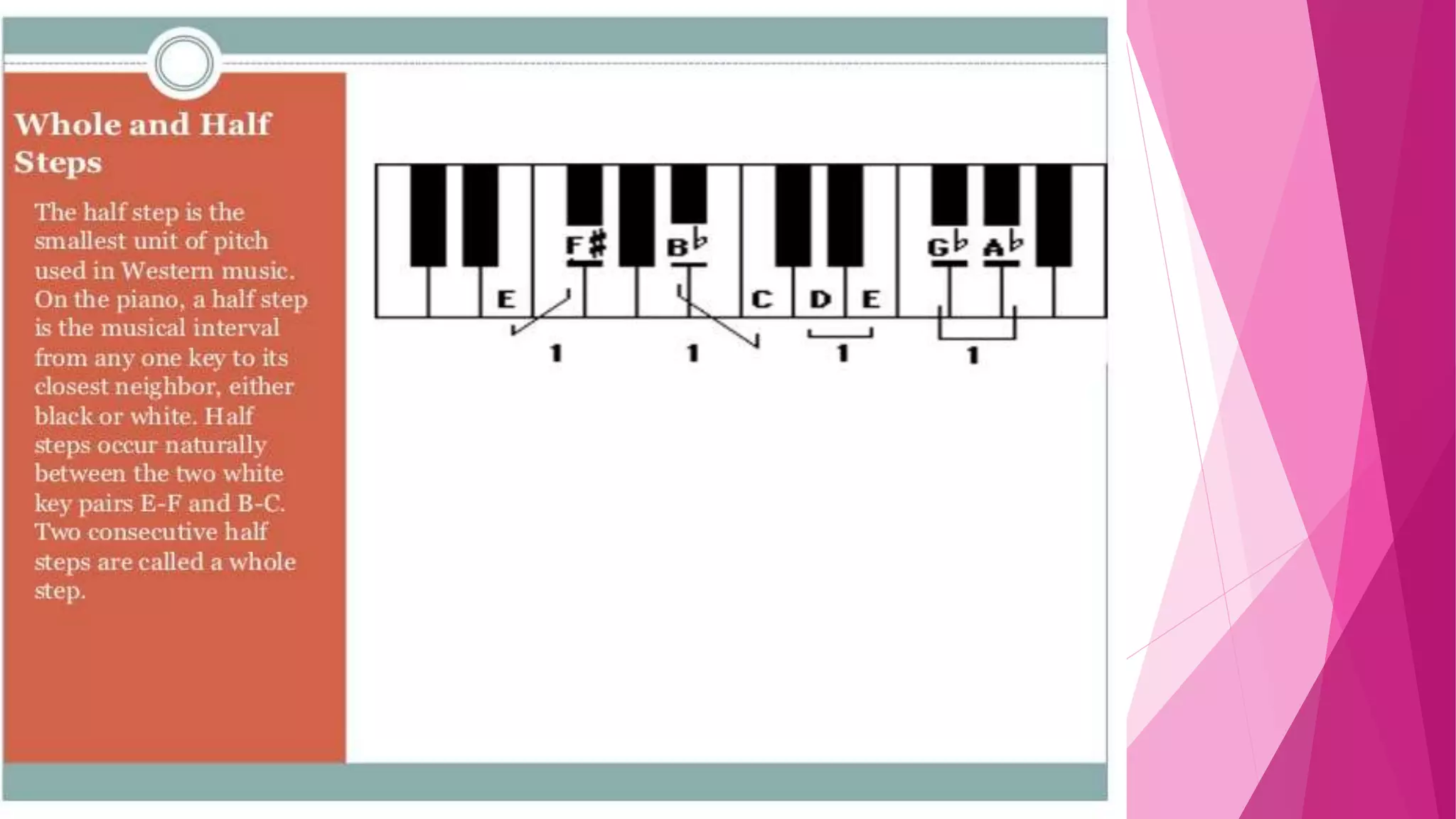

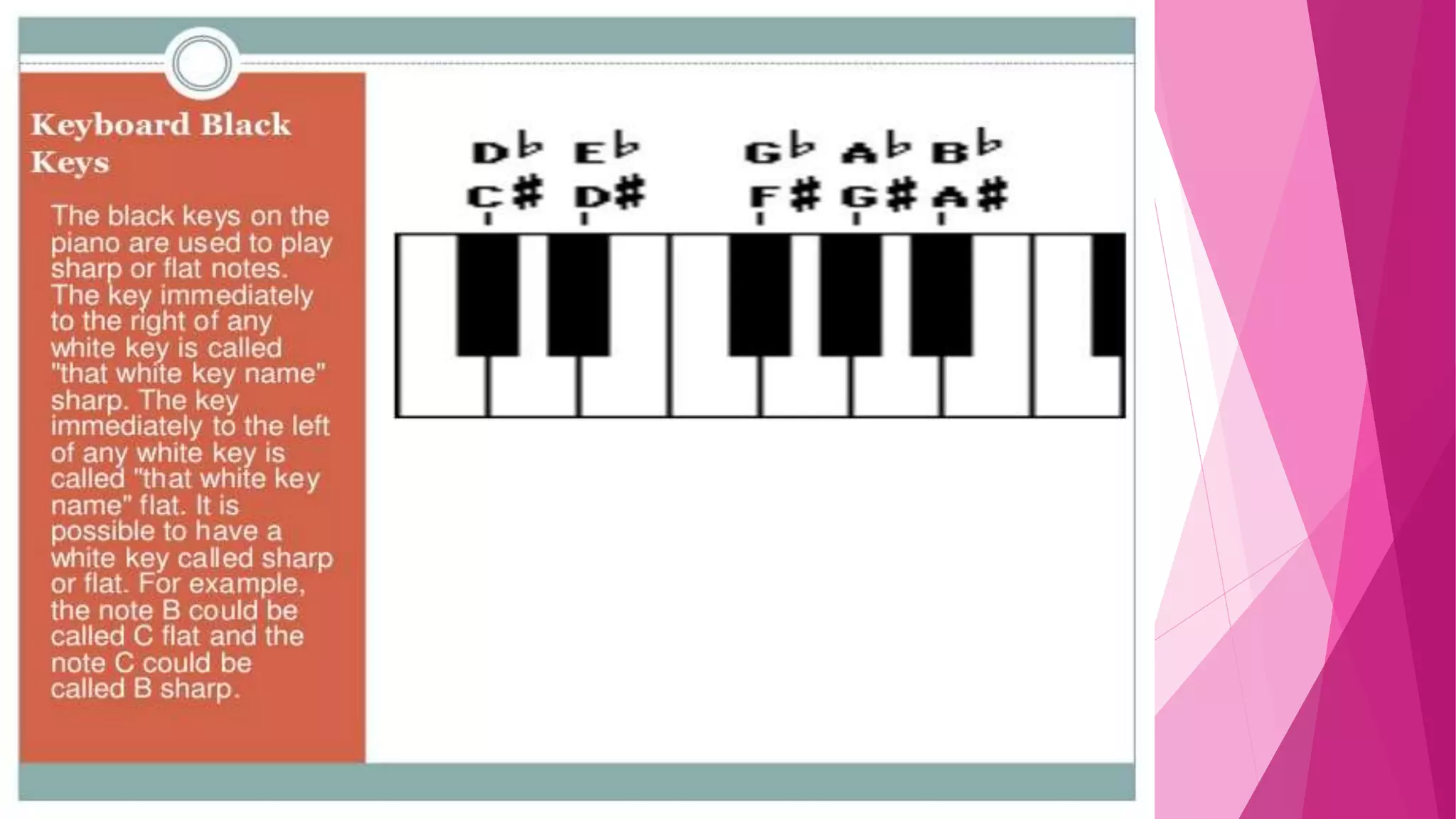

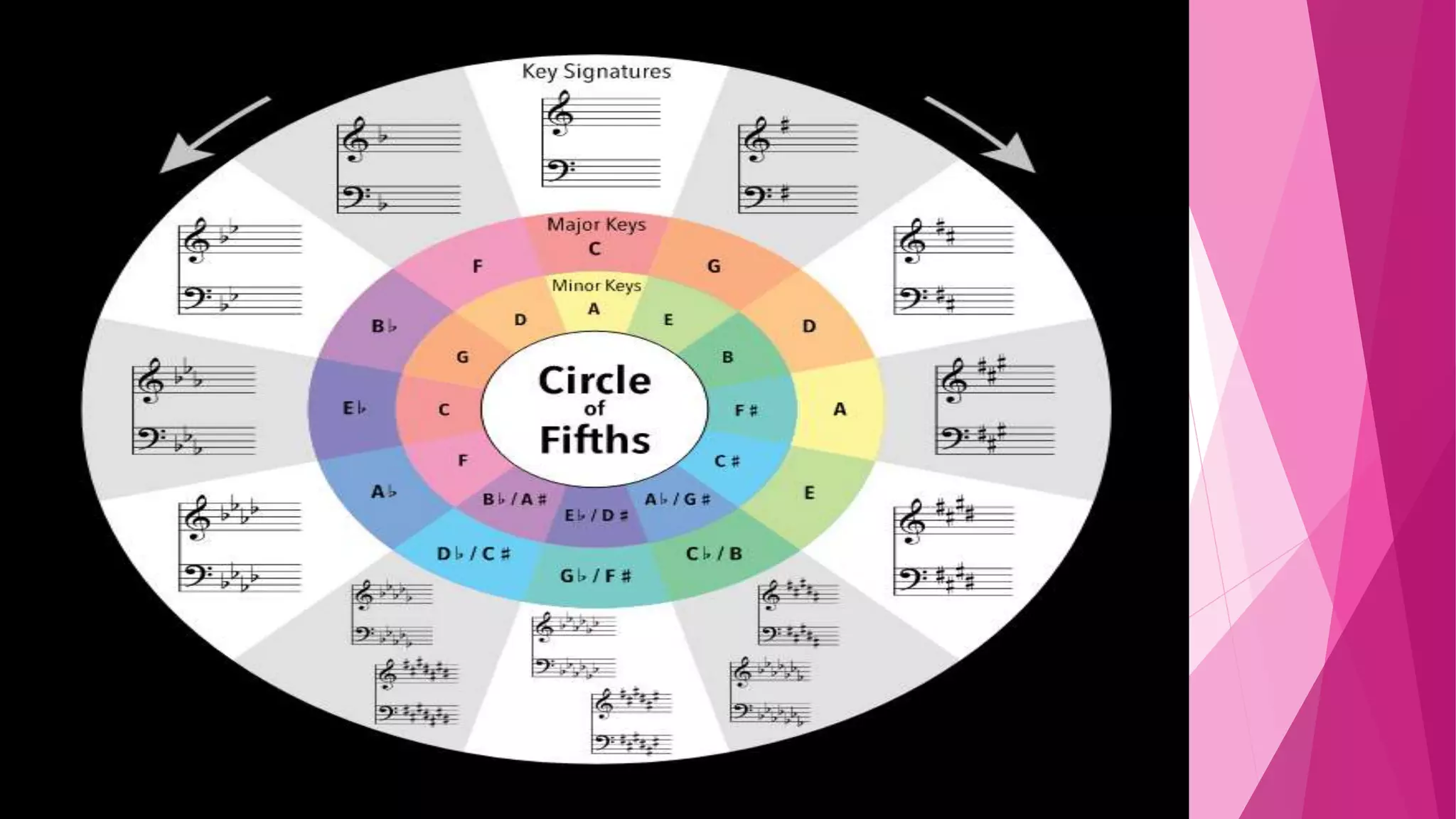

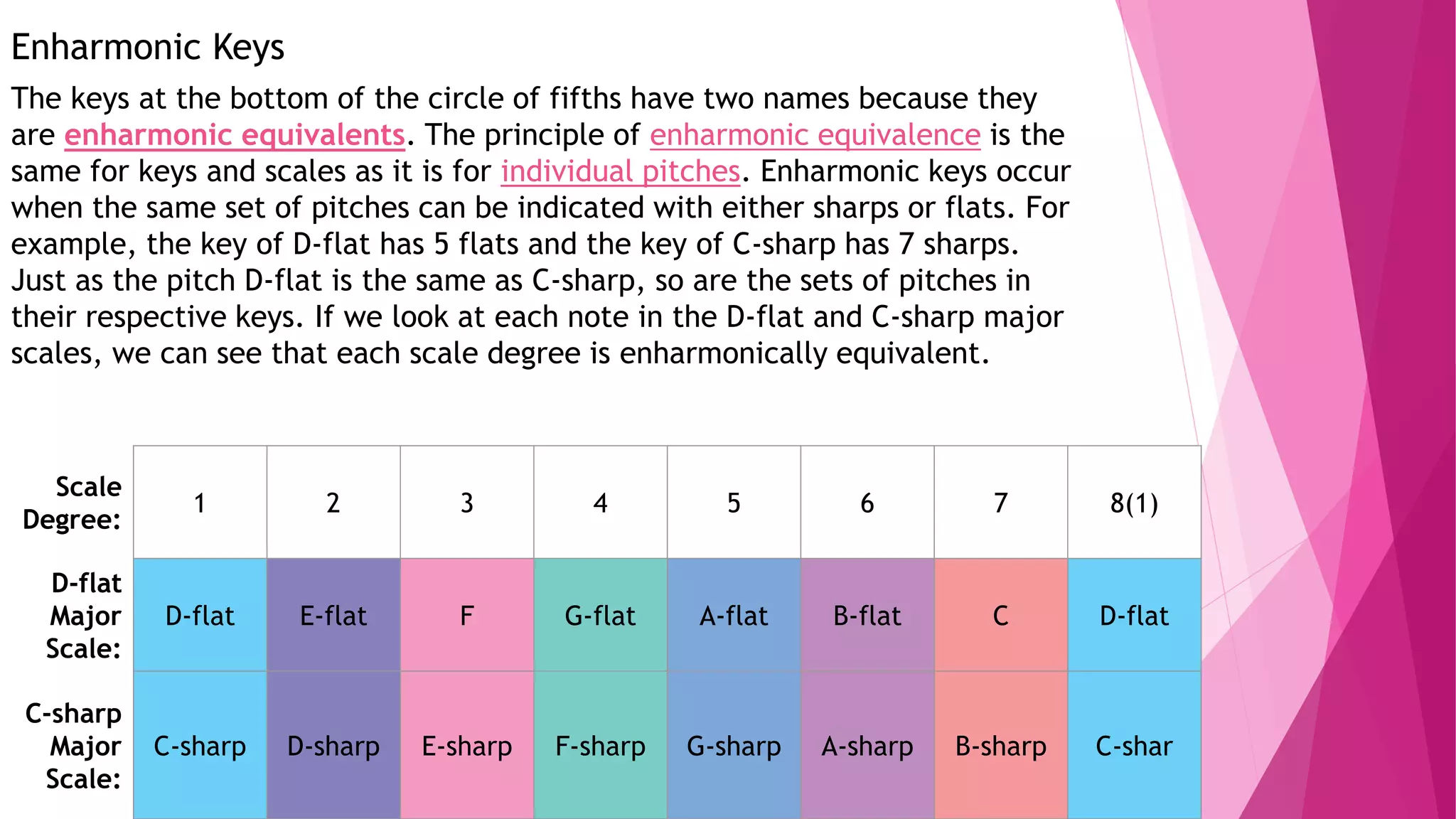

The document discusses key signatures, explaining their appearance and the concepts of sharp and flat notes in music. It details enharmonic spelling, its types, and the relationship between keys on the circle of fifths, including parallel and relative keys. Additionally, it explores how composers use enharmonic reinterpretation and respelling for the sake of convenience to facilitate modulation and reading for performers.