The document contains a series of questions and definitions related to music terminology such as dynamics, pitch, melody, rhythm, and harmony, along with practical exercises focused on musical terms and concepts. Additionally, it discusses the concepts of analysis of variance (ANOVA) in statistical studies, demonstrating how to compare means across groups while controlling for errors. It illustrates procedures for computing sums of squares, degrees of freedom, and p-values using Excel, providing an APA-style conclusion based on statistical results.

![Music 100%.rtfd/1__#[email protected]%!#__button.gif

__MACOSX/Music

100%.rtfd/._1__#[email protected]%!#__button.gif

Music 100%.rtfd/1__#[email protected]%!#__icon.png

__MACOSX/Music

100%.rtfd/._1__#[email protected]%!#__icon.png

Music 100%.rtfd/2__#[email protected]%!#__button.gif

__MACOSX/Music

100%.rtfd/._2__#[email protected]%!#__button.gif

Music 100%.rtfd/button.gif

__MACOSX/Music 100%.rtfd/._button.gif

Music 100%.rtfd/downtick.png

__MACOSX/Music 100%.rtfd/._downtick.png

Music 100%.rtfd/icon.png

__MACOSX/Music 100%.rtfd/._icon.png

Music 100%.rtfd/record.gif

__MACOSX/Music 100%.rtfd/._record.gif

Music 100%.rtfd/TXT.rtf

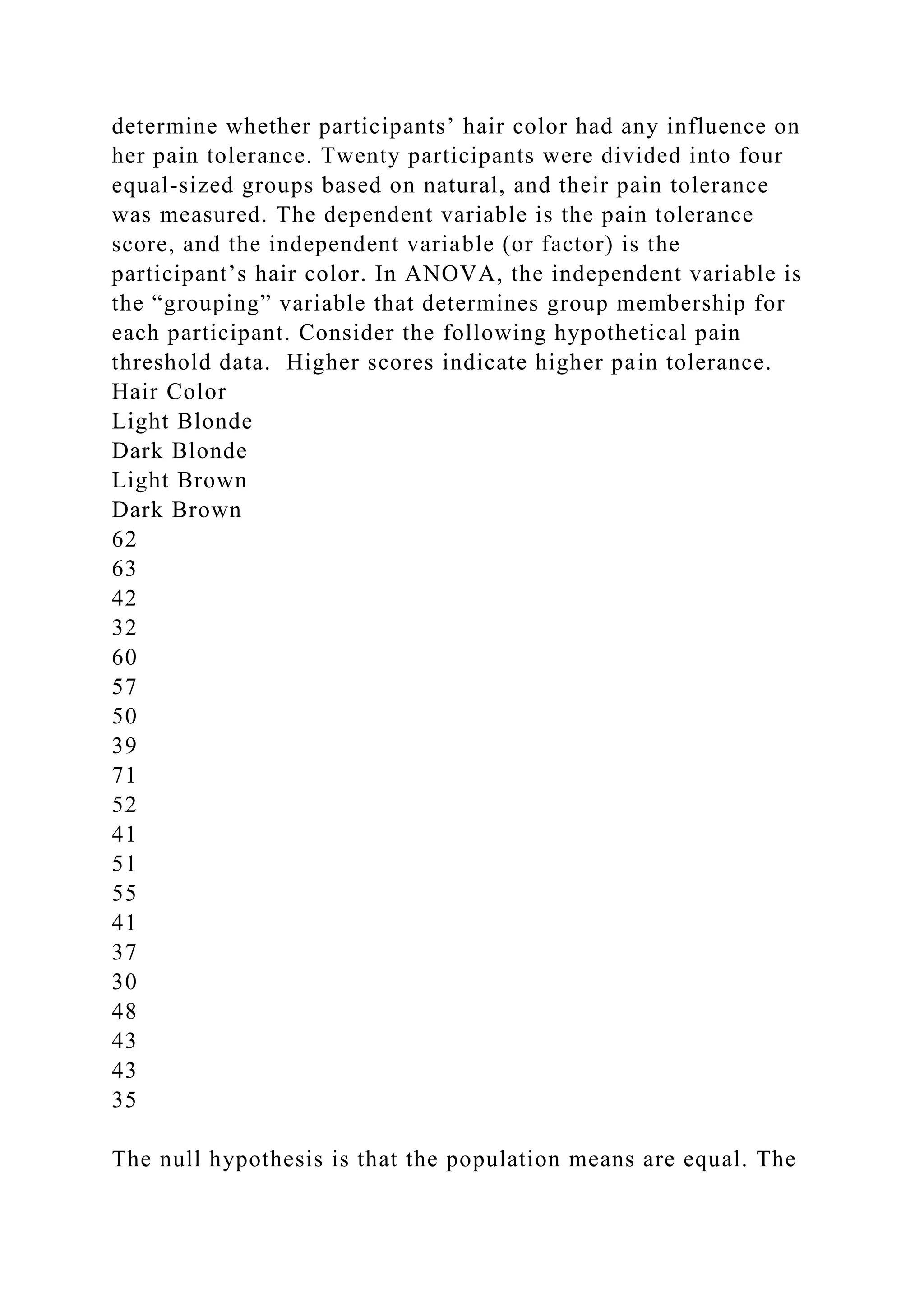

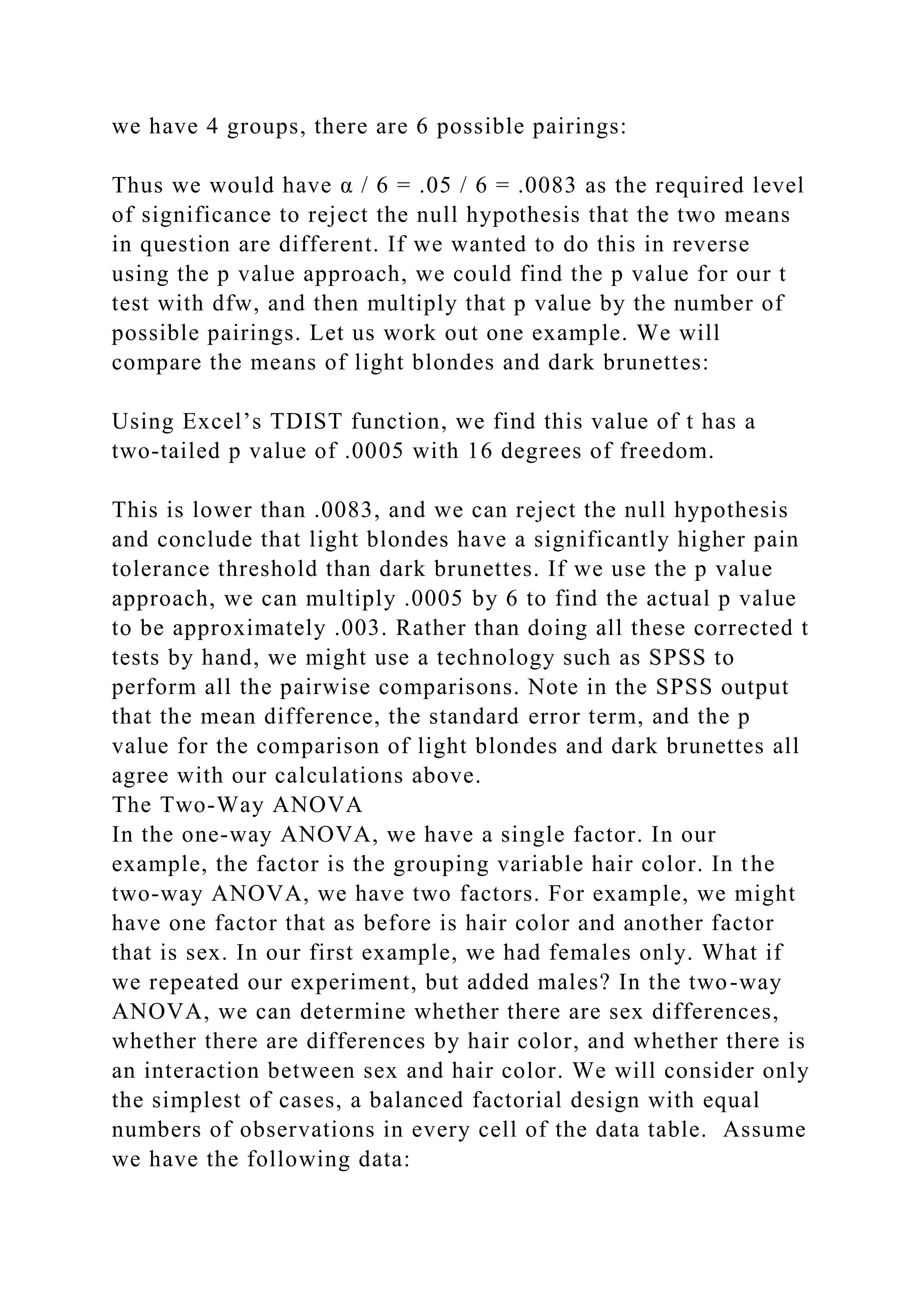

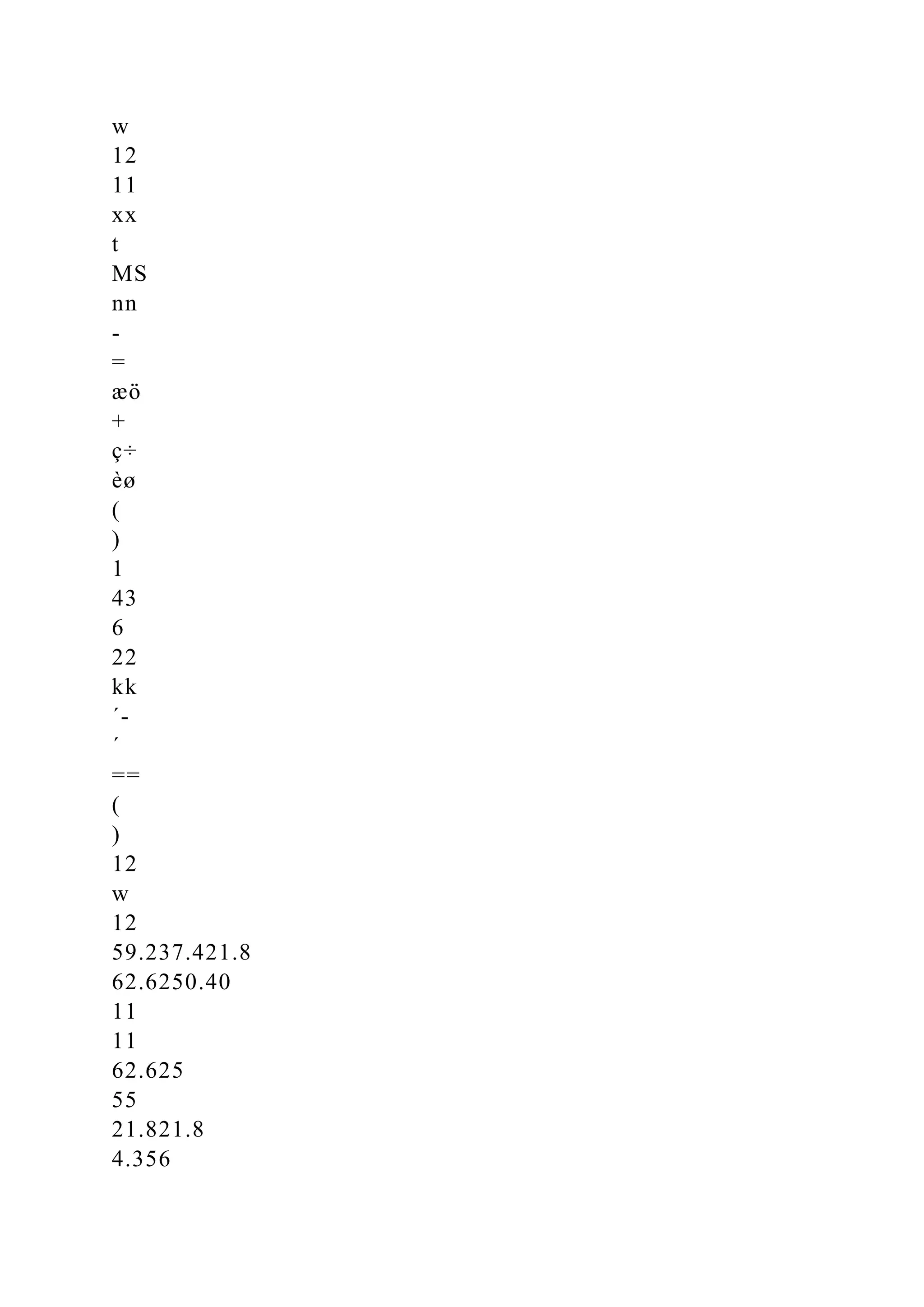

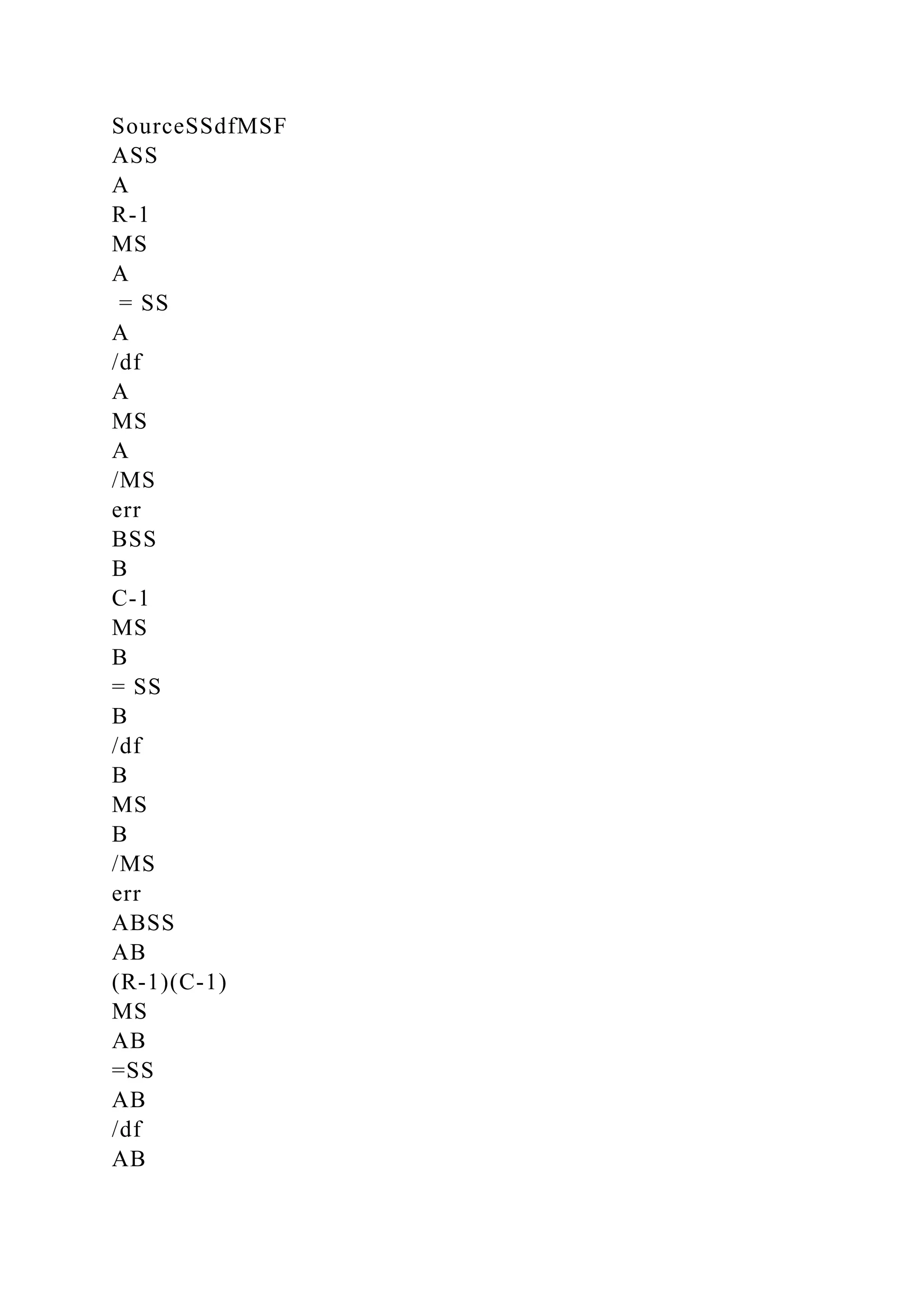

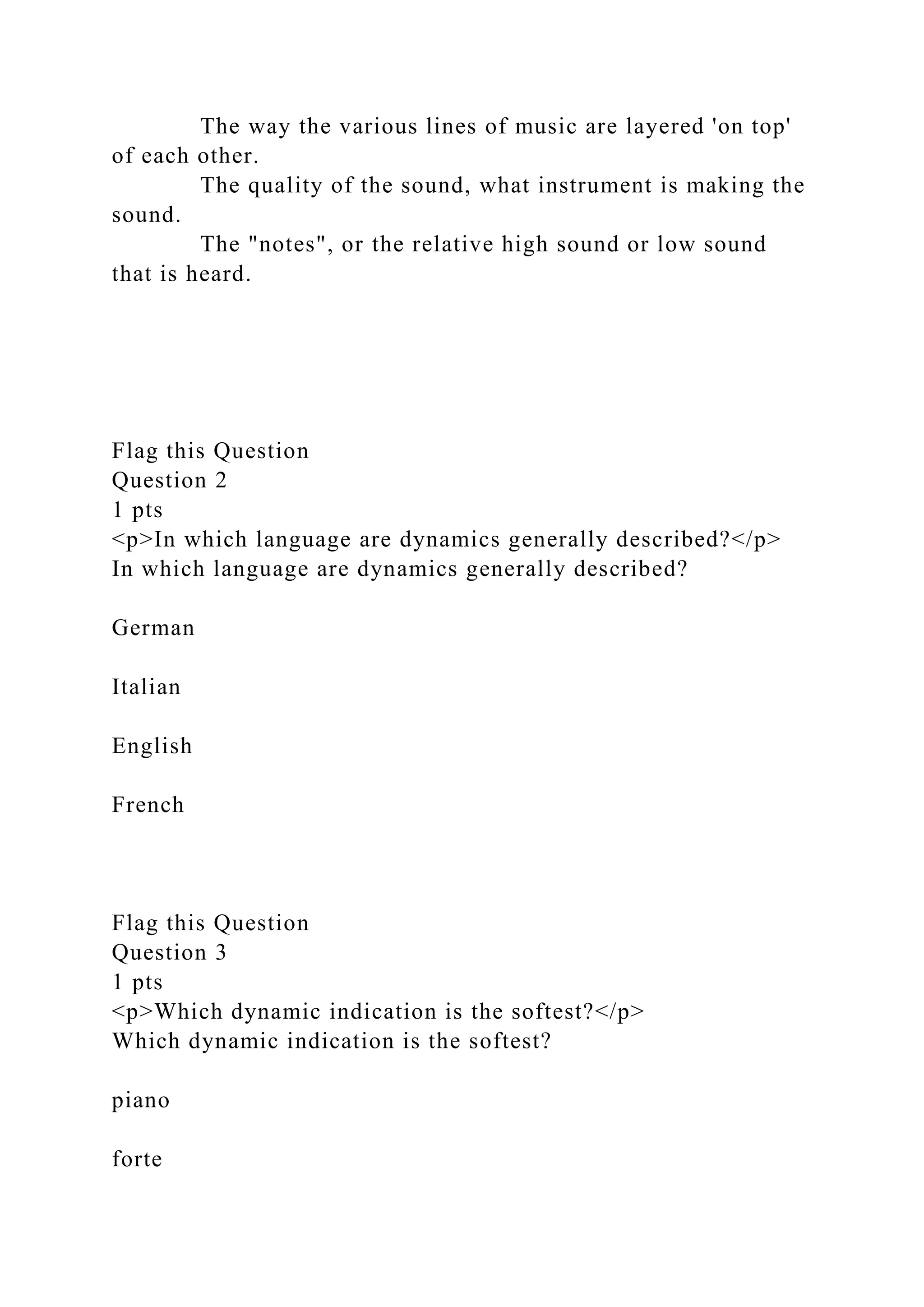

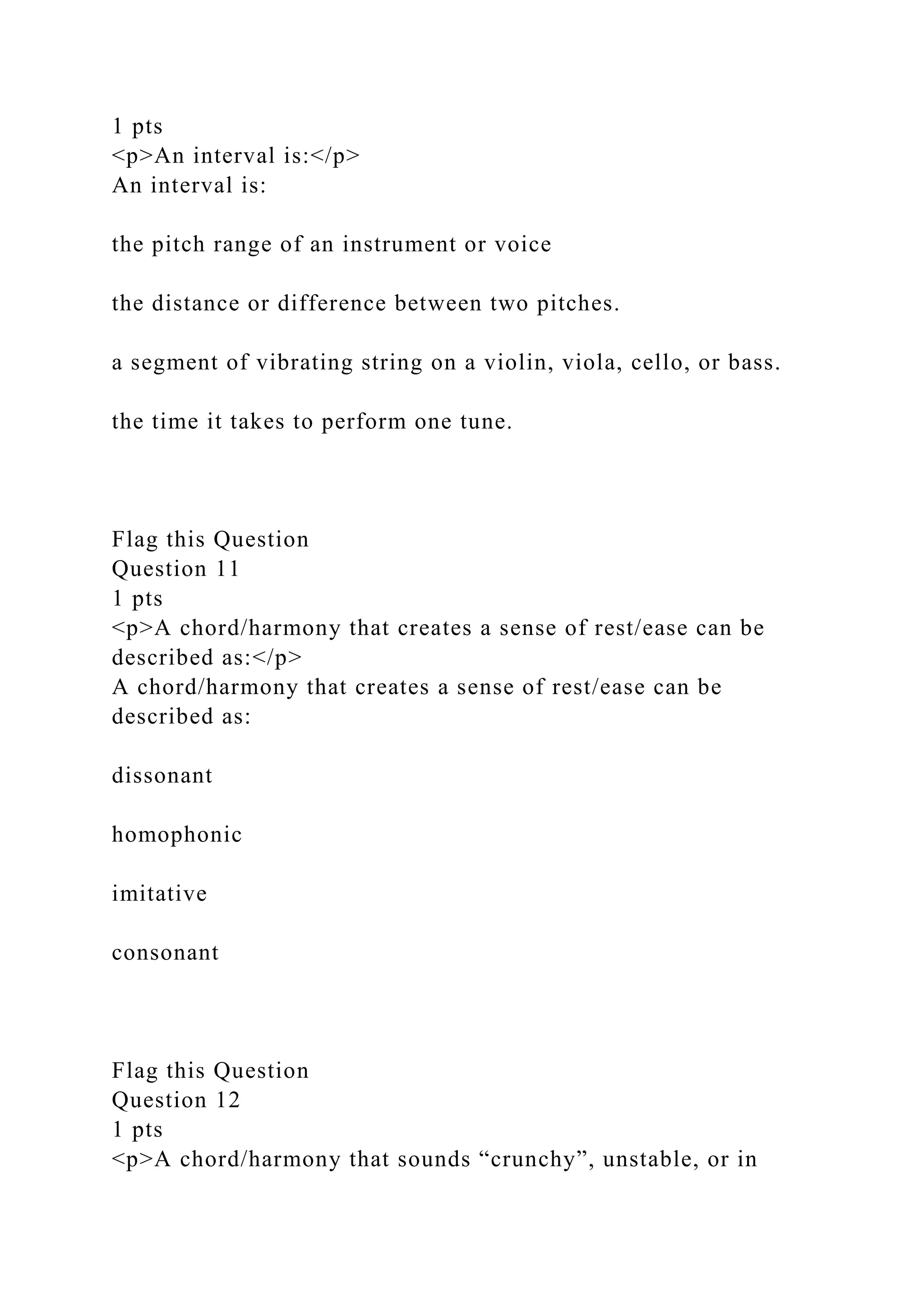

Match the vocabulary word and it's definition.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/music100-221109044802-b21f41e9/75/Music-100-rtfd1__-email-protected-__button-gif__MACOSX-docx-1-2048.jpg)

![Dynamic

[ Choose ]

Pitches organized with rhythm as a recognizable unit

that has a beginning, middle and end. Like words in a sentence.

The largest structure, it is created by repetition and

contrast of the smaller Structures.

The time aspect of music, the length of the sound being

made.

How loud or soft the sound is.

More than one pitch sounding at the same time.

The way the various lines of music are layered 'on top'

of each other.

The quality of the sound, what instrument is making the

sound.

The "notes", or the relative high sound or low sound

that is heard.

Pitch

[ Choose ]

Pitches organized with rhythm as a recognizable unit

that has a beginning, middle and end. Like words in a sentence.

The largest structure, it is created by repetition and

contrast of the smaller Structures.

The time aspect of music, the length of the sound being

made.

How loud or soft the sound is.

More than one pitch sounding at the same time.

The way the various lines of music are layered 'on top'

of each other.

The quality of the sound, what instrument is making the

sound.

The "notes", or the relative high sound or low sound

that is heard.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/music100-221109044802-b21f41e9/75/Music-100-rtfd1__-email-protected-__button-gif__MACOSX-docx-2-2048.jpg)

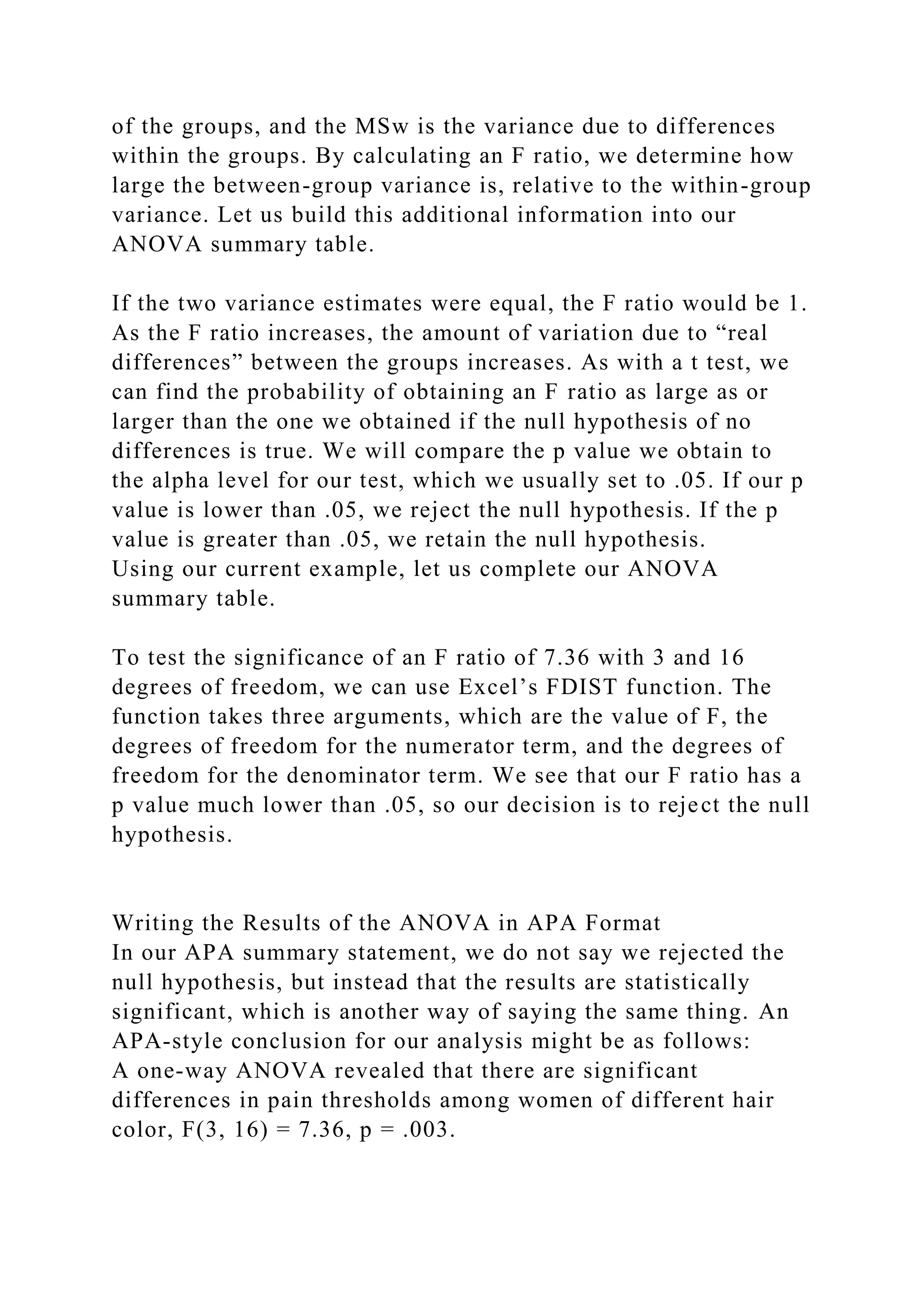

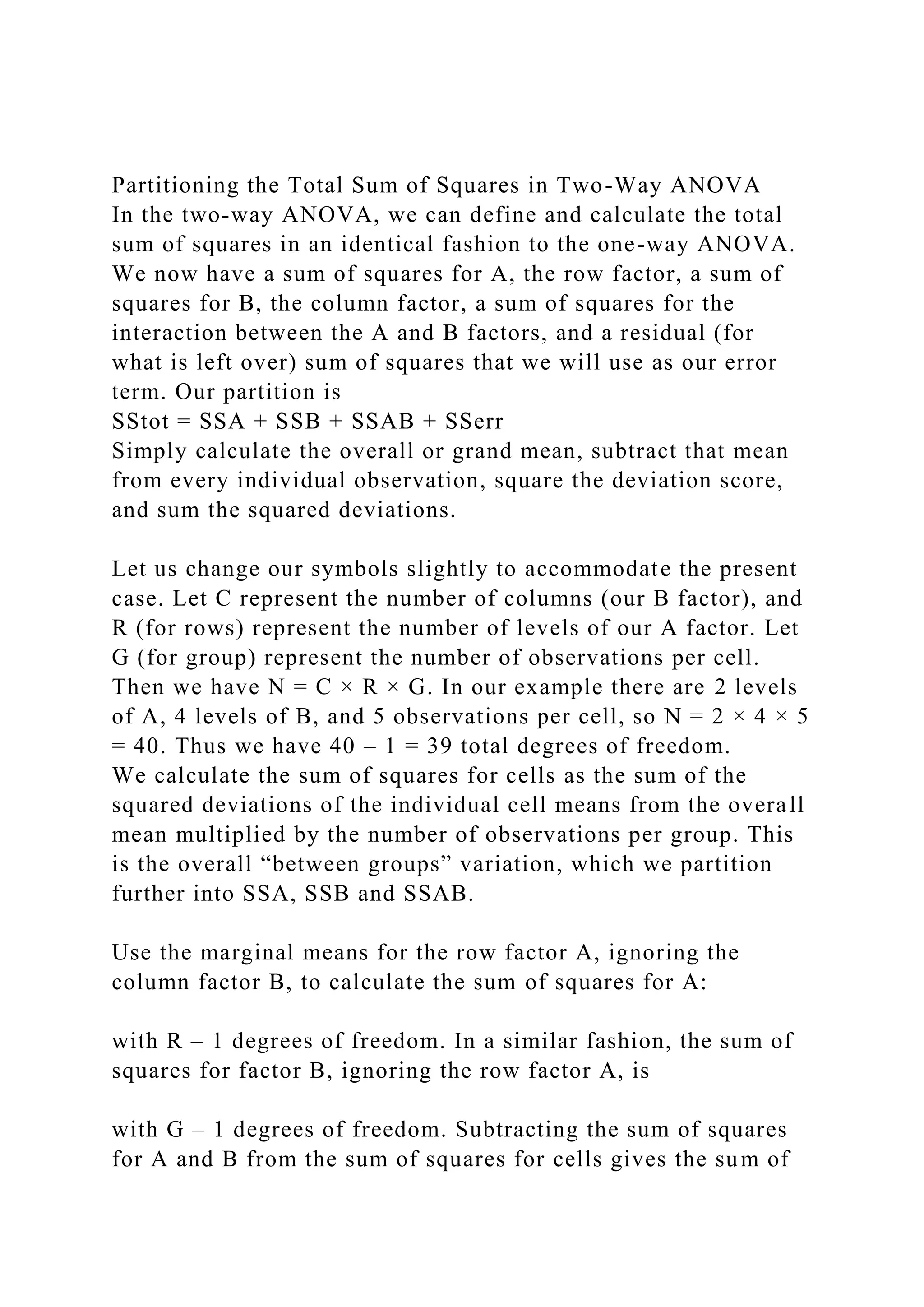

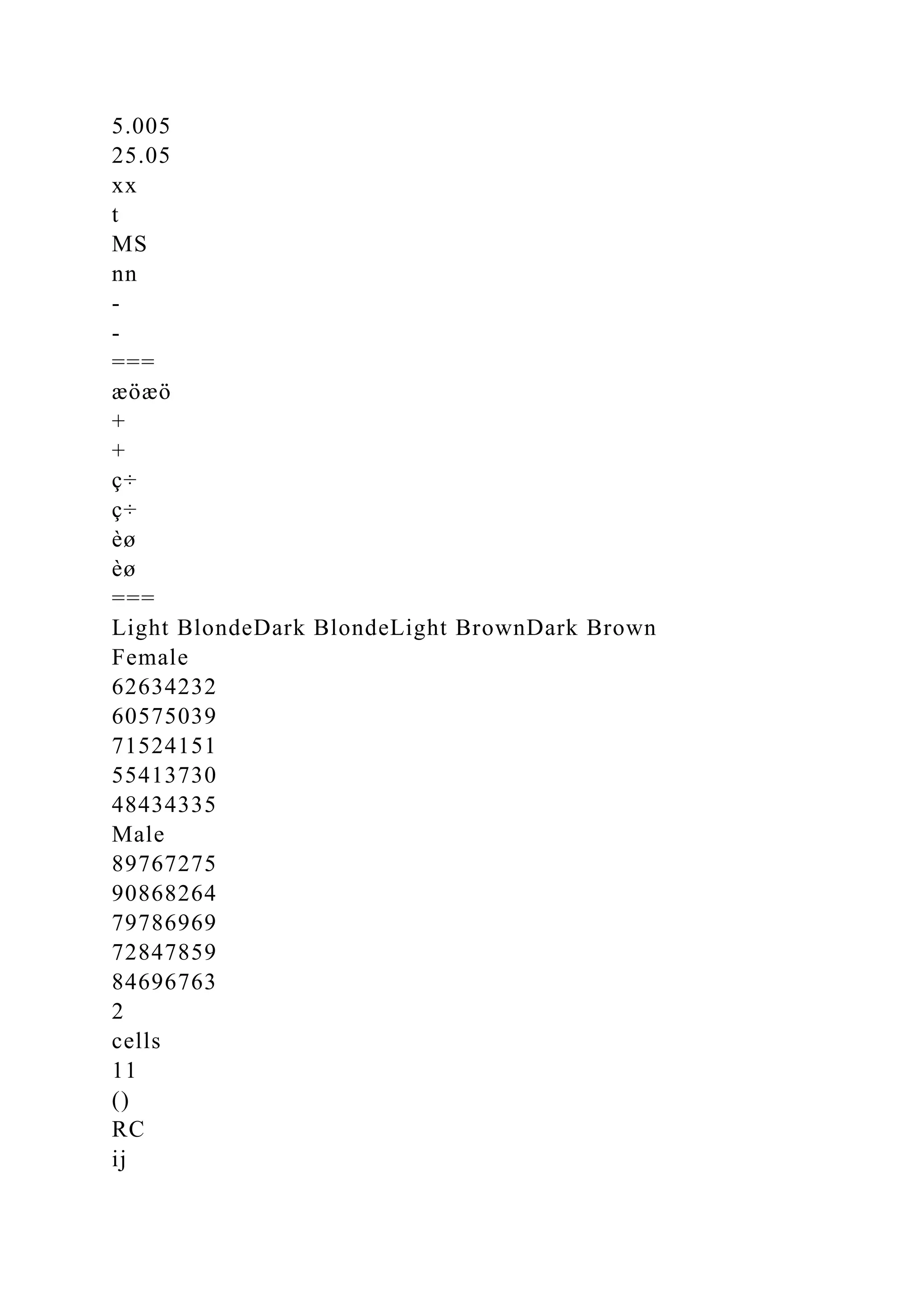

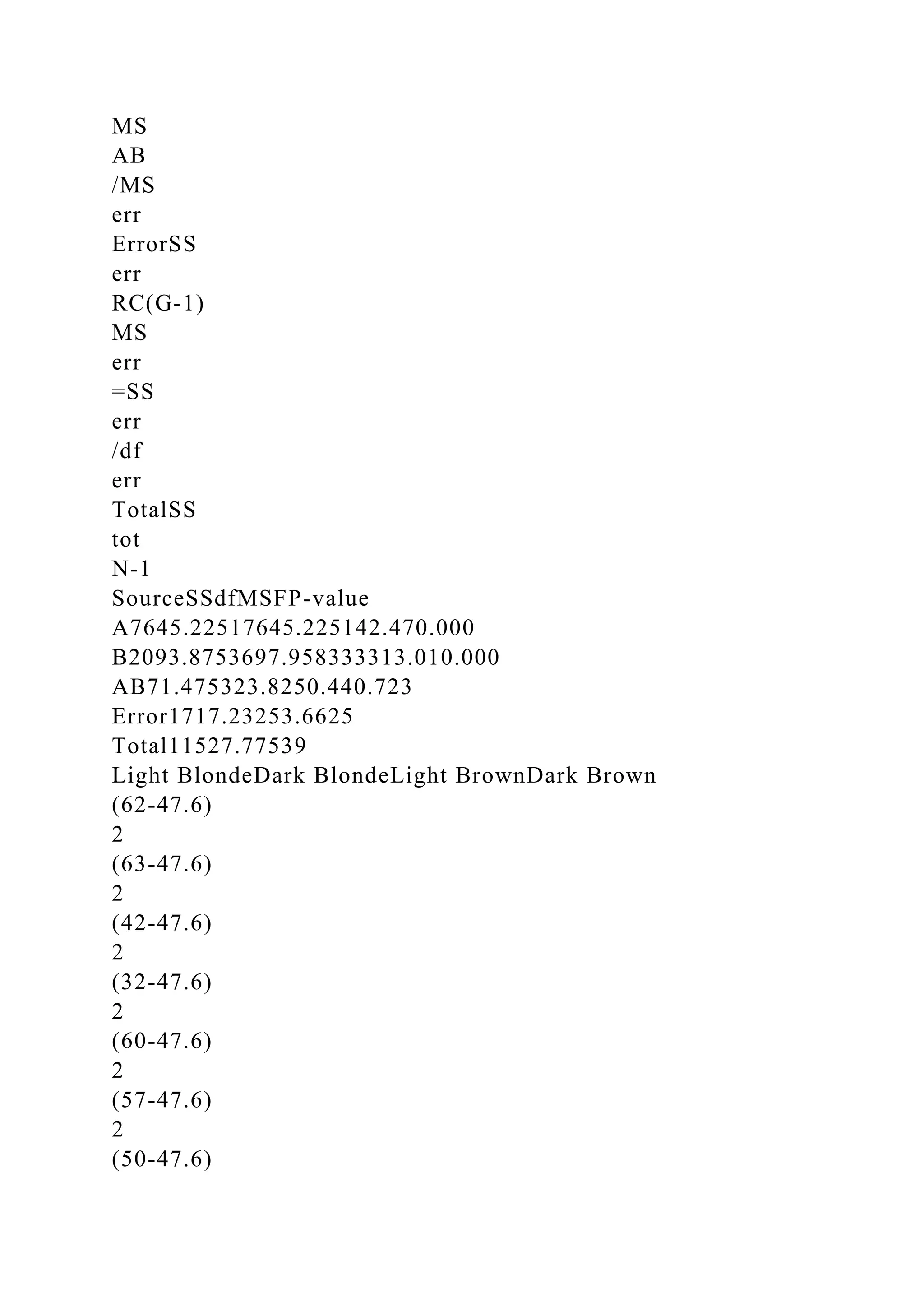

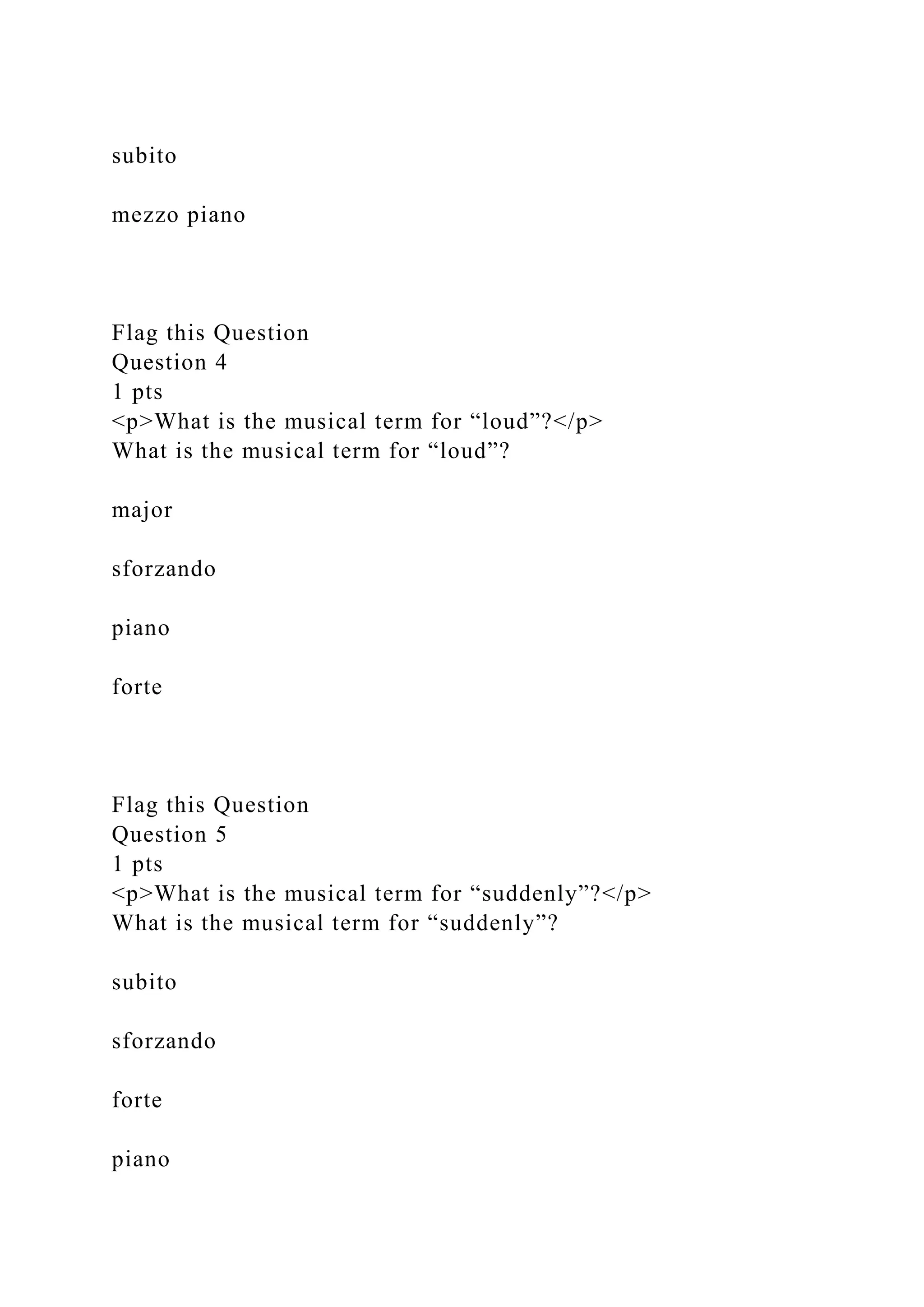

![Tone Color/Timber

[ Choose ]

Pitches organized with rhythm as a recognizable unit

that has a beginning, middle and end. Like words in a sentence.

The largest structure, it is created by repetition and

contrast of the smaller Structures.

The time aspect of music, the length of the sound being

made.

How loud or soft the sound is.

More than one pitch sounding at the same time.

The way the various lines of music are layered 'on top'

of each other.

The quality of the sound, what instrument is making the

sound.

The "notes", or the relative high sound or low sound

that is heard.

Melody

[ Choose ]

Pitches organized with rhythm as a recognizable unit

that has a beginning, middle and end. Like words in a sentence.

The largest structure, it is created by repetition and

contrast of the smaller Structures.

The time aspect of music, the length of the sound being

made.

How loud or soft the sound is.

More than one pitch sounding at the same time.

The way the various lines of music are layered 'on top'

of each other.

The quality of the sound, what instrument is making the

sound.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/music100-221109044802-b21f41e9/75/Music-100-rtfd1__-email-protected-__button-gif__MACOSX-docx-3-2048.jpg)

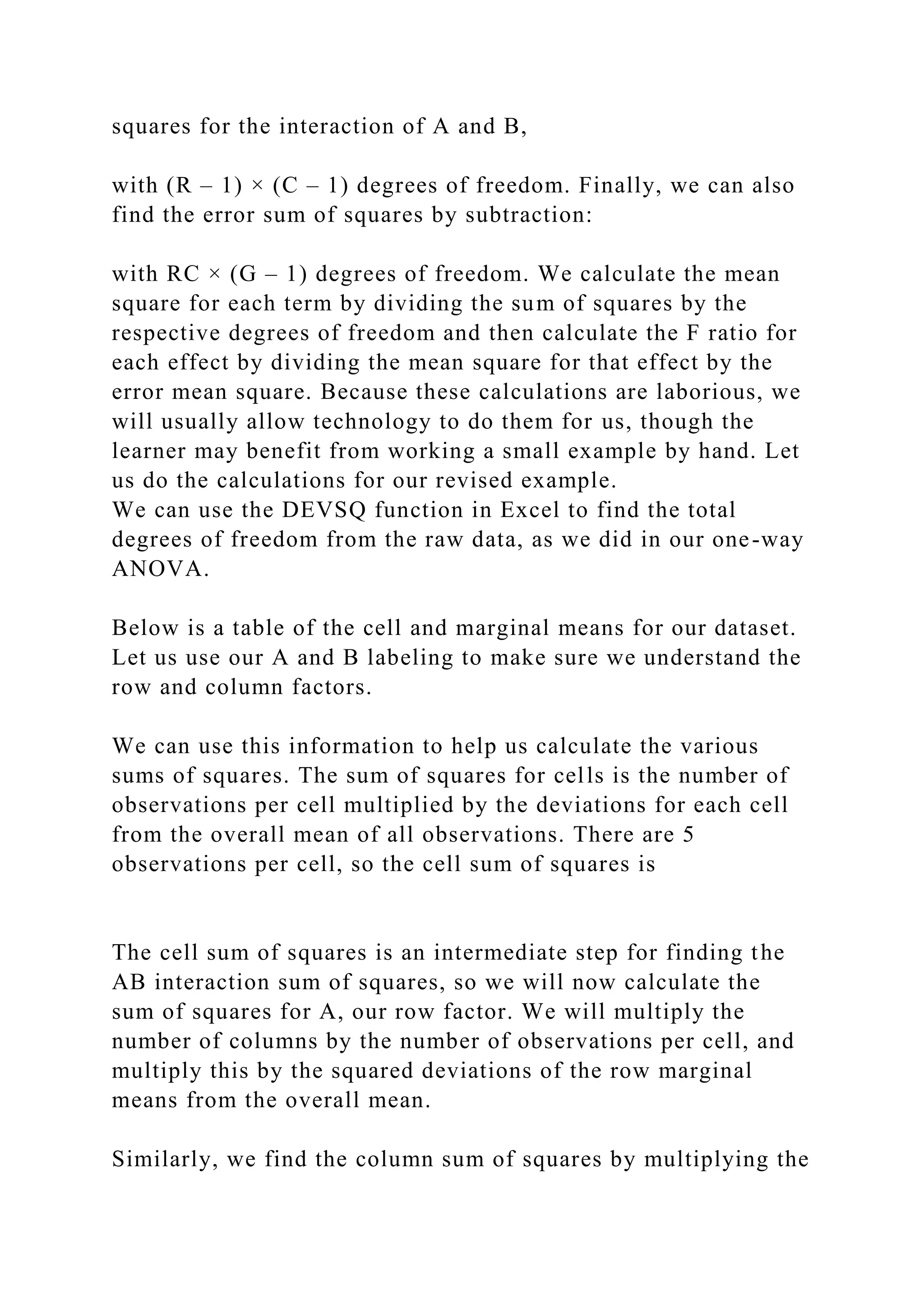

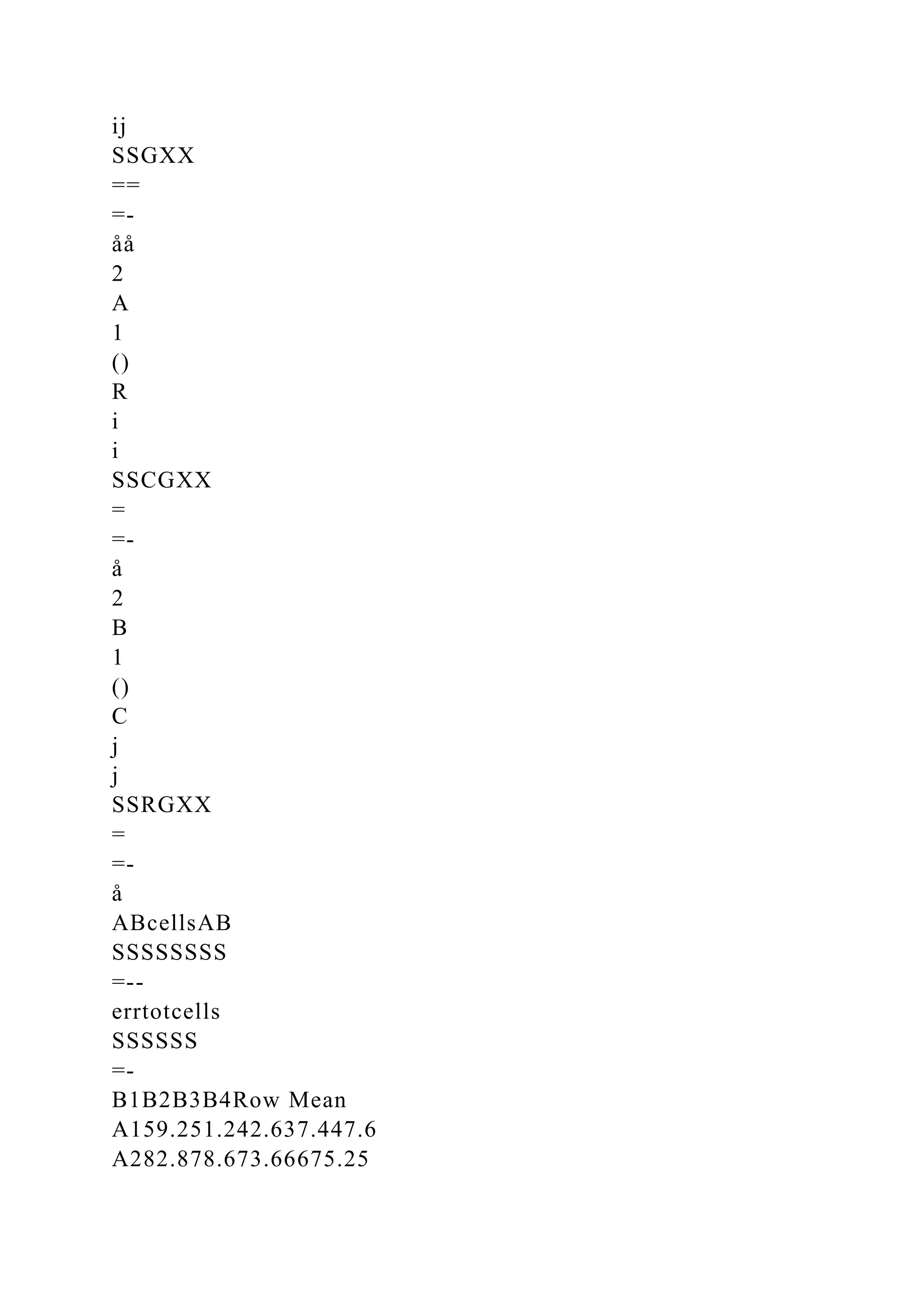

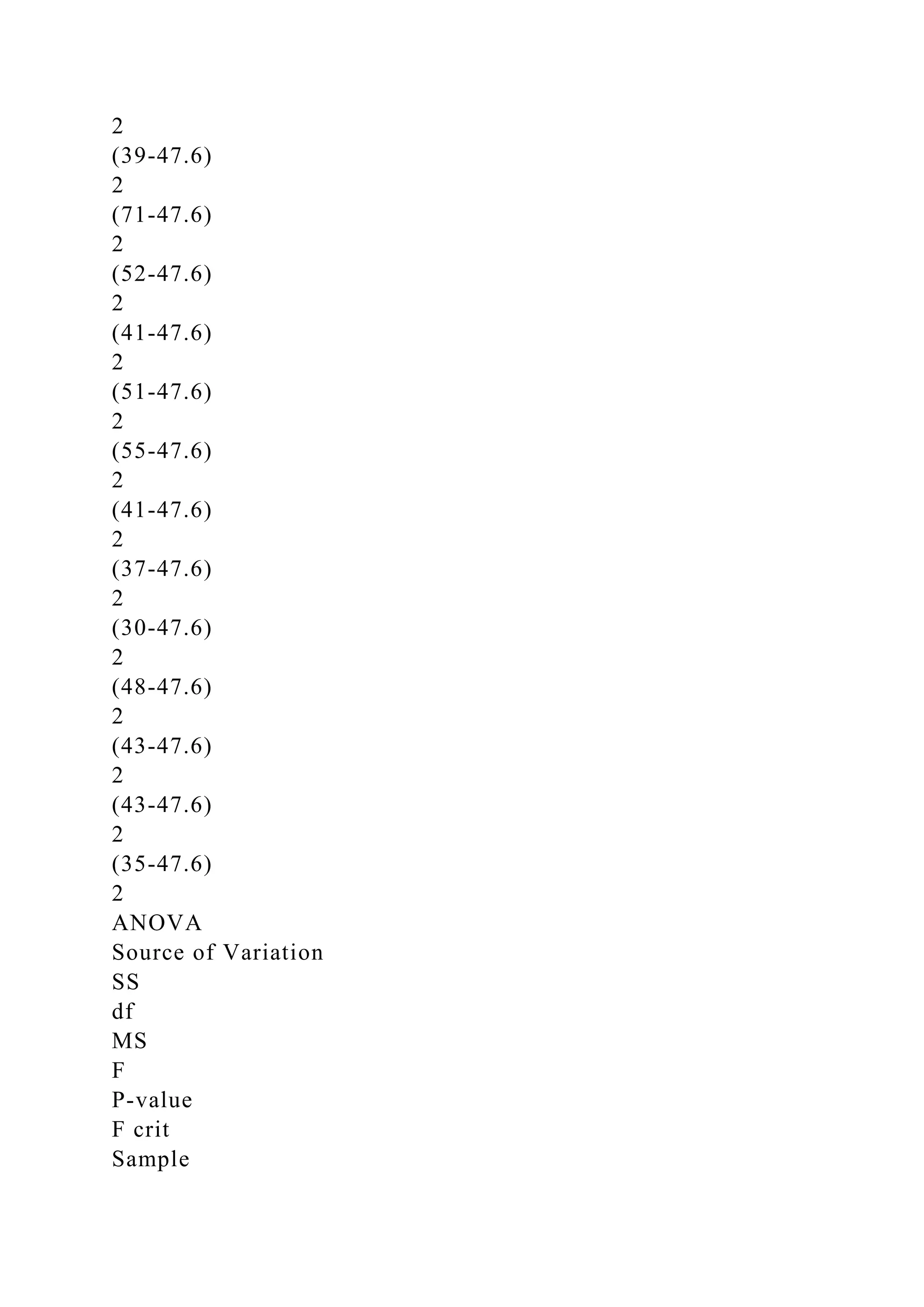

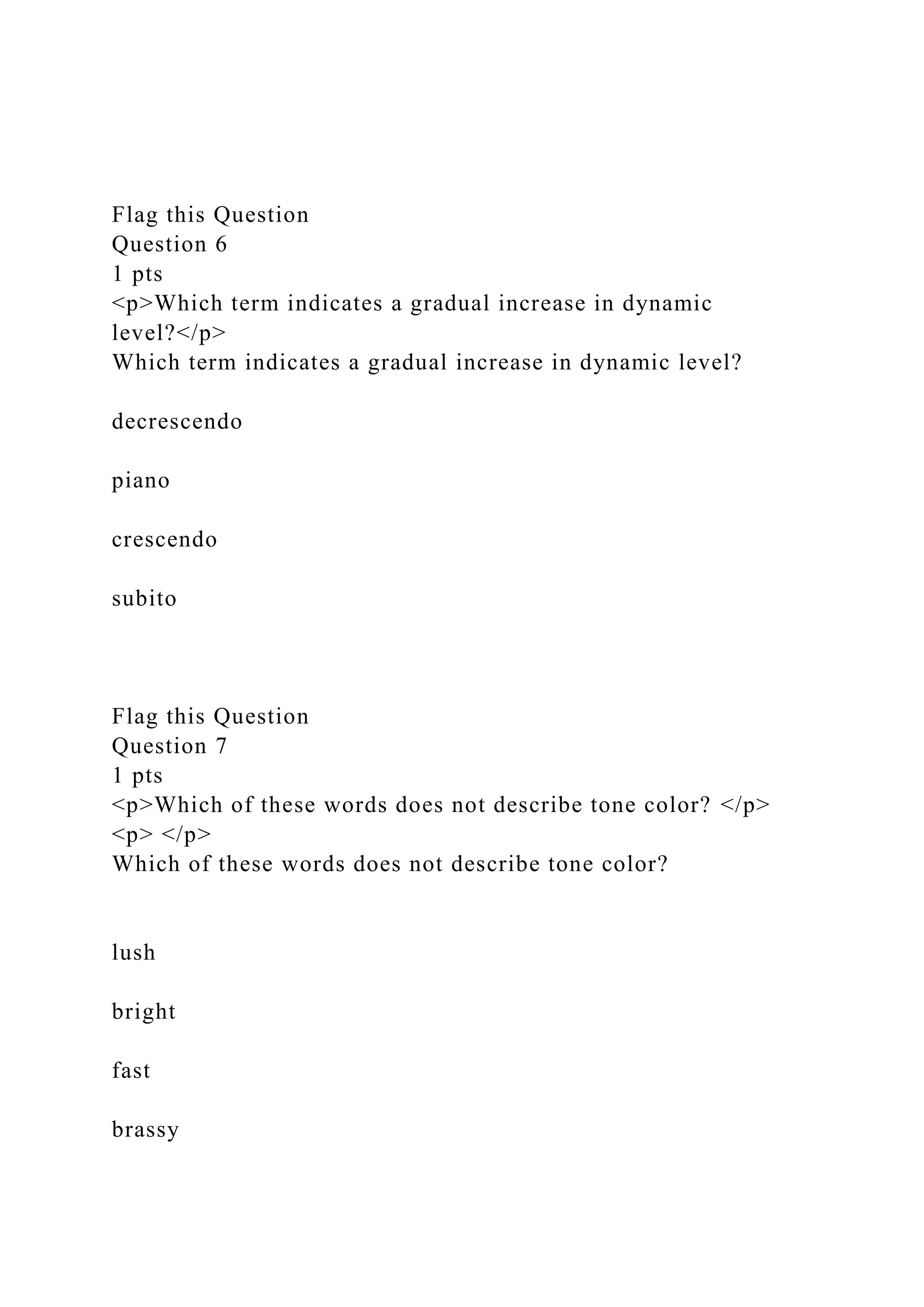

![The "notes", or the relative high sound or low sound

that is heard.

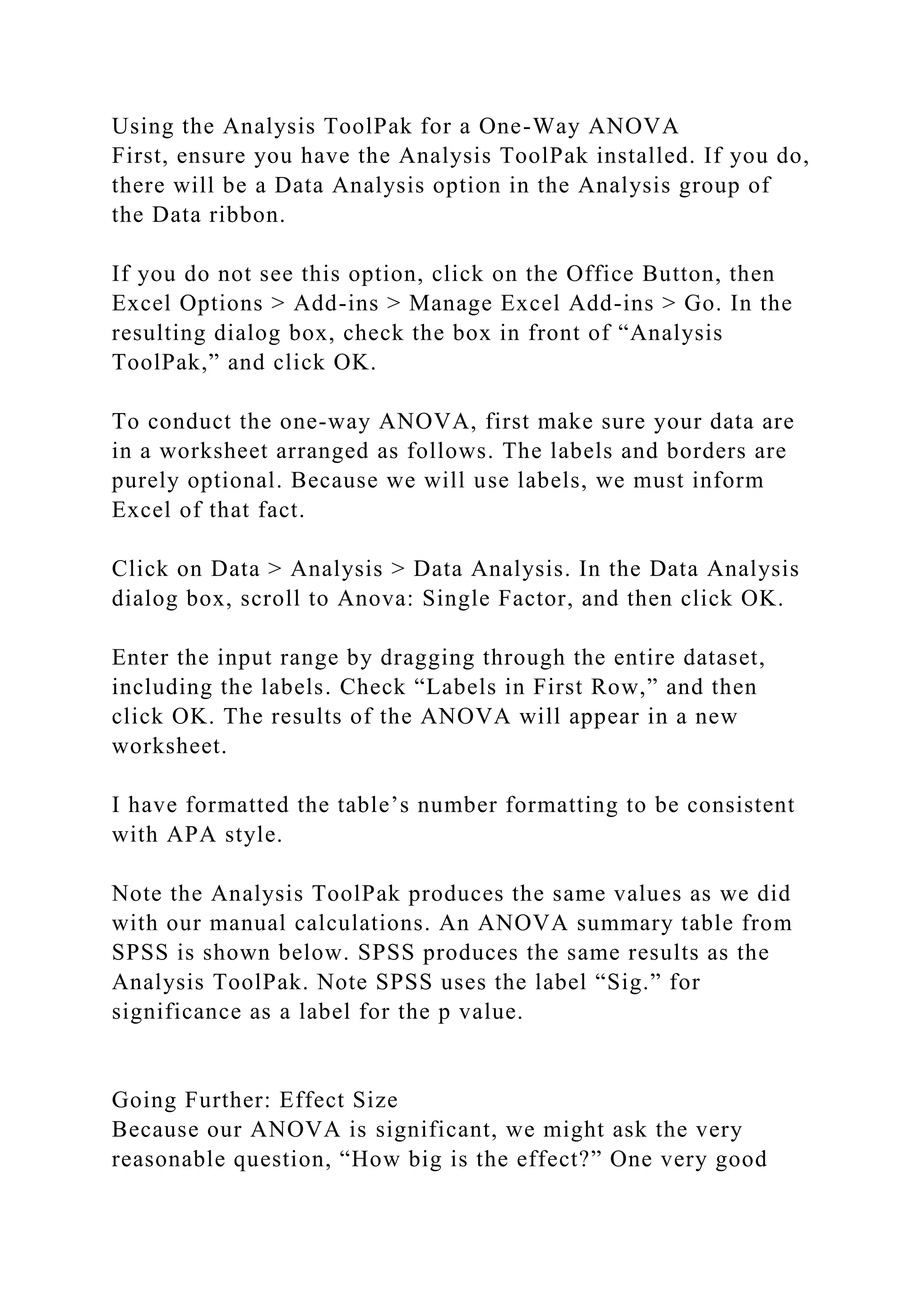

Rhythm

[ Choose ]

Pitches organized with rhythm as a recognizable unit

that has a beginning, middle and end. Like words in a sentence.

The largest structure, it is created by repetition and

contrast of the smaller Structures.

The time aspect of music, the length of the sound being

made.

How loud or soft the sound is.

More than one pitch sounding at the same time.

The way the various lines of music are layered 'on top'

of each other.

The quality of the sound, what instrument is making the

sound.

The "notes", or the relative high sound or low sound

that is heard.

Harmony

[ Choose ]

Pitches organized with rhythm as a recognizable unit

that has a beginning, middle and end. Like words in a sentence.

The largest structure, it is created by repetition and

contrast of the smaller Structures.

The time aspect of music, the length of the sound being

made.

How loud or soft the sound is.

More than one pitch sounding at the same time.

The way the various lines of music are layered 'on top'

of each other.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/music100-221109044802-b21f41e9/75/Music-100-rtfd1__-email-protected-__button-gif__MACOSX-docx-4-2048.jpg)

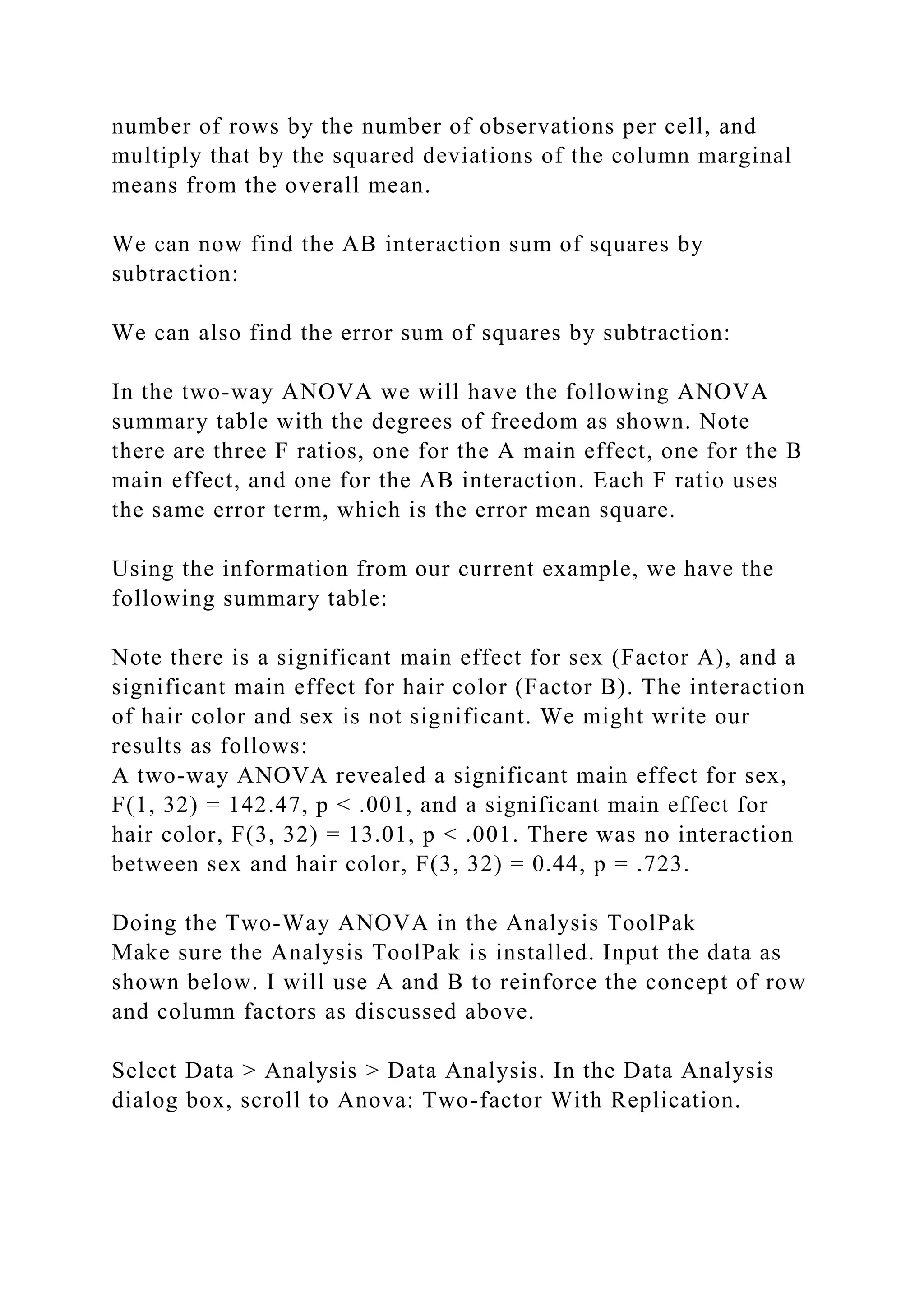

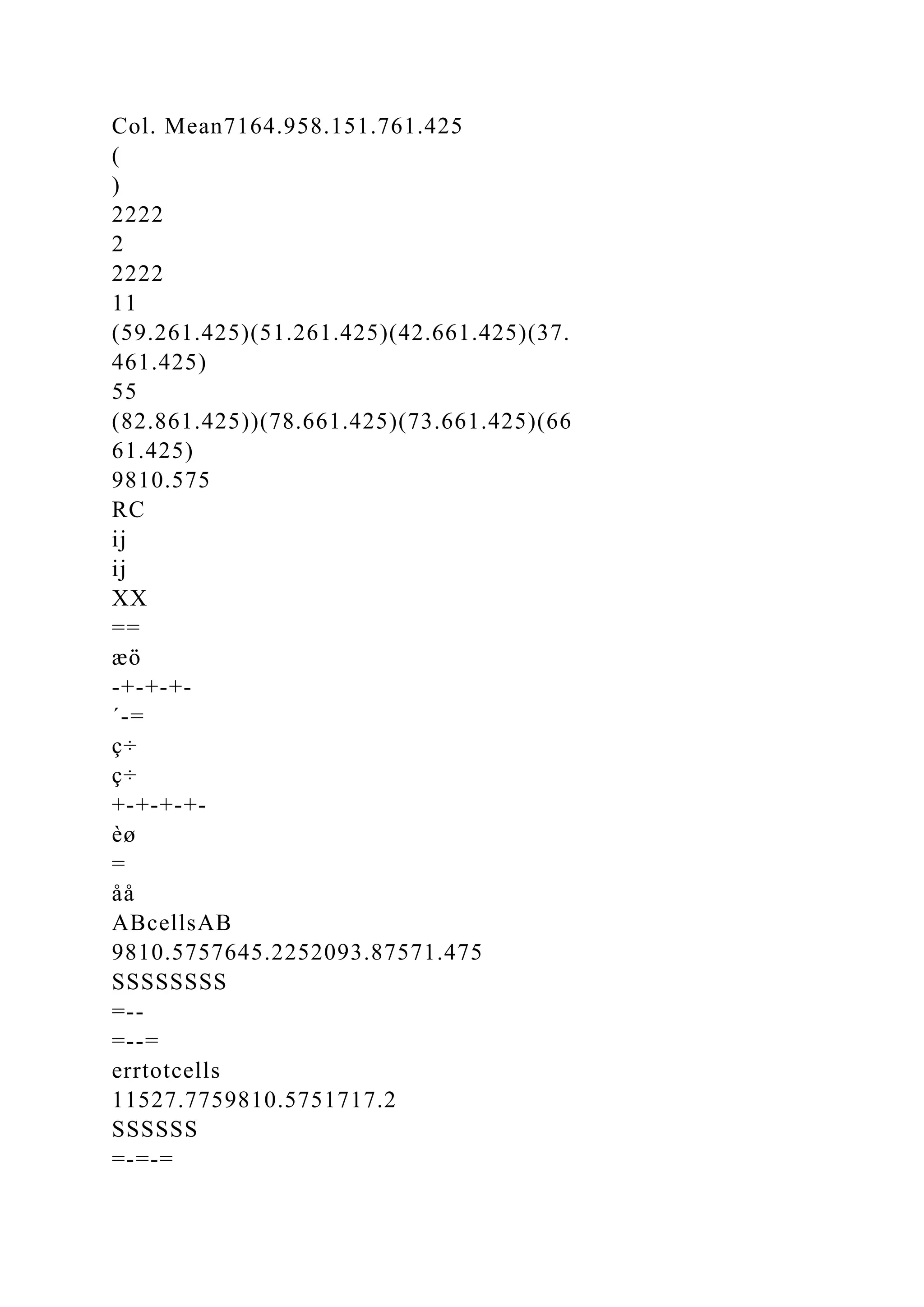

![The quality of the sound, what instrument is making the

sound.

The "notes", or the relative high sound or low sound

that is heard.

Texture

[ Choose ]

Pitches organized with rhythm as a recognizable unit

that has a beginning, middle and end. Like words in a sentence.

The largest structure, it is created by repetition and

contrast of the smaller Structures.

The time aspect of music, the length of the sound being

made.

How loud or soft the sound is.

More than one pitch sounding at the same time.

The way the various lines of music are layered 'on top'

of each other.

The quality of the sound, what instrument is making the

sound.

The "notes", or the relative high sound or low sound

that is heard.

Form

[ Choose ]

Pitches organized with rhythm as a recognizable unit

that has a beginning, middle and end. Like words in a sentence.

The largest structure, it is created by repetition and

contrast of the smaller Structures.

The time aspect of music, the length of the sound being

made.

How loud or soft the sound is.

More than one pitch sounding at the same time.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/music100-221109044802-b21f41e9/75/Music-100-rtfd1__-email-protected-__button-gif__MACOSX-docx-5-2048.jpg)

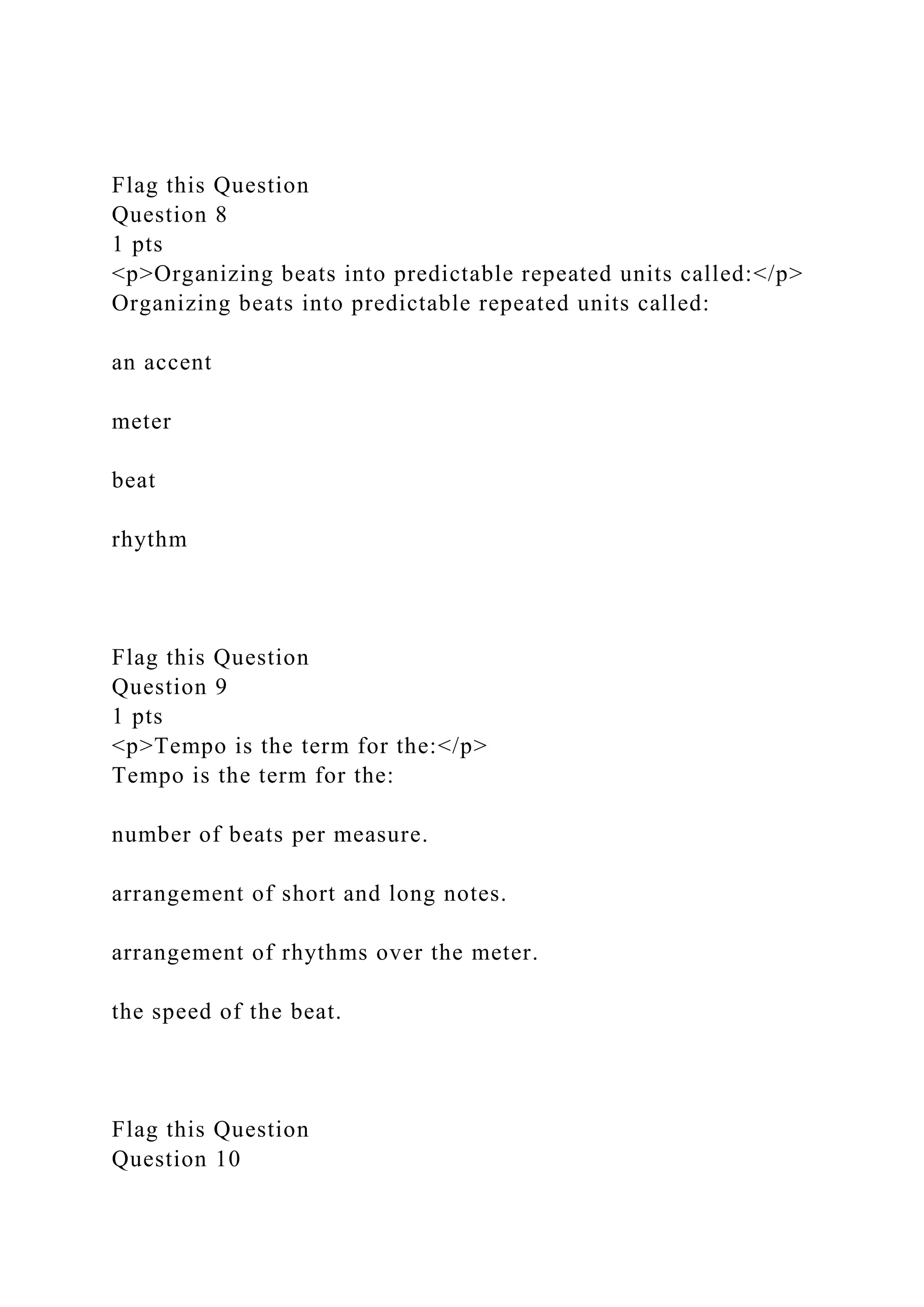

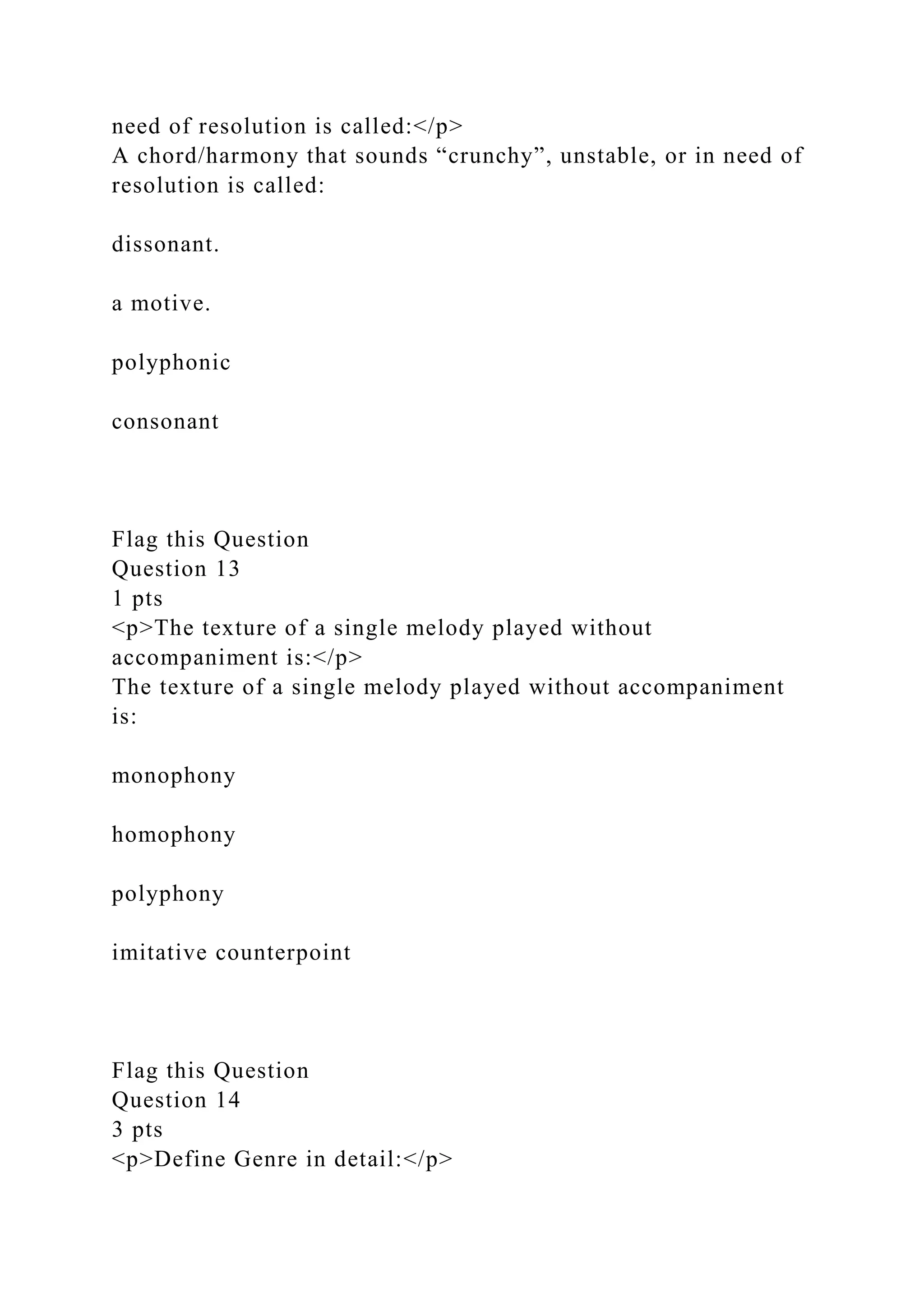

![Define Genre in detail:

Keyboard Shortcuts

button.gif ¬1__#[email protected]%!#__button.gif

¬2__#[email protected]%!#__button.gif ¬icon.png

¬1__#[email protected]%!#__icon.png ¬downtick.png

¬record.gif ¬Font SizeParagraph

Flag this Question

Question 15

3 pts

<p>Define Era and explain how they are ‘created’</p>

Define Era and explain how they are ‘created’

__MACOSX/Music 100%.rtfd/._TXT.rtf

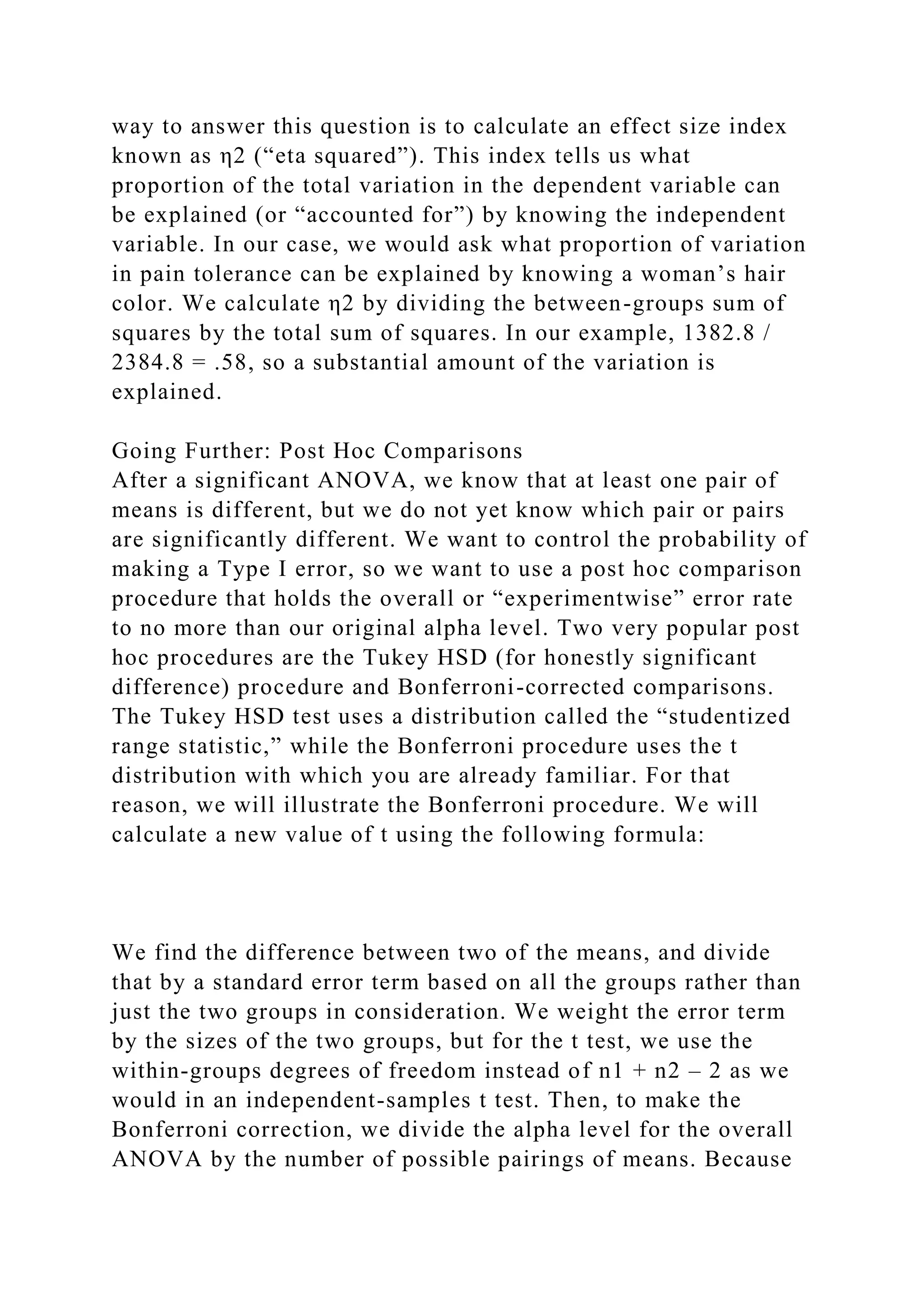

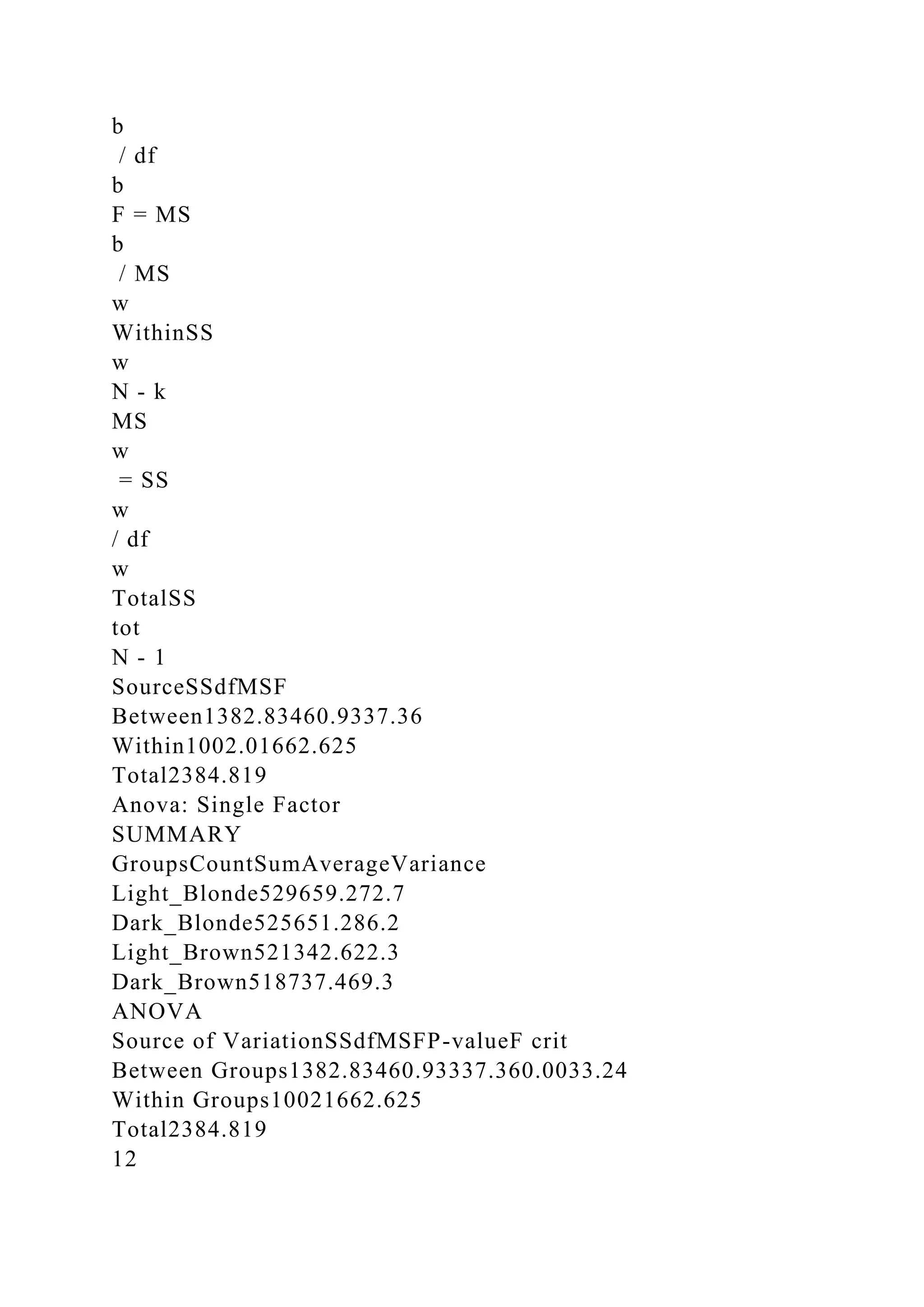

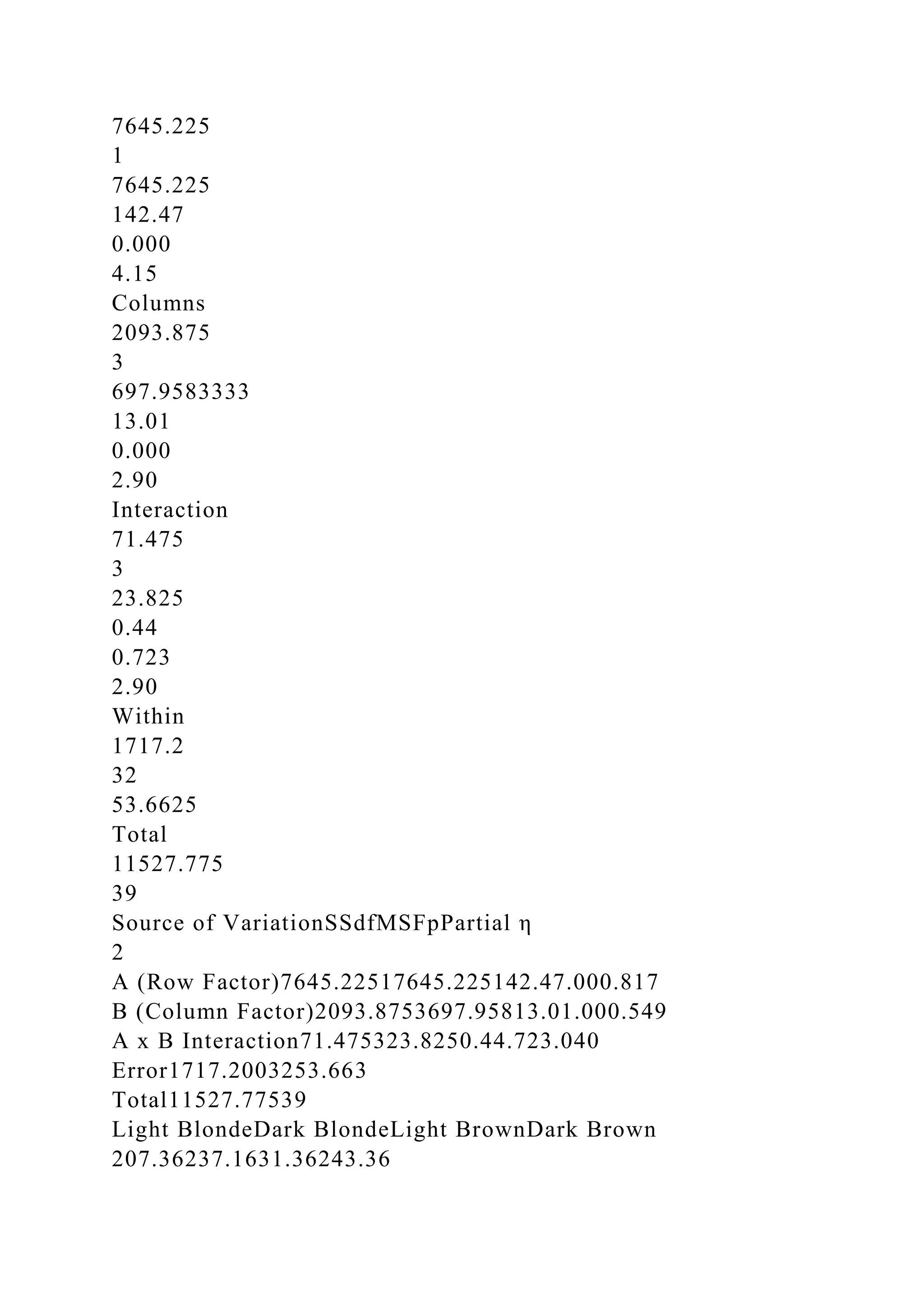

One-Way and Two-Way ANOVA in Excel

Larry A. Pace, Ph.D.

Let us learn to conduct and interpret a one-way ANOVA and a

two-way ANOVA for a balanced factorial design in Excel, using

the Analysis ToolPak. We will perform the calculations by use

of formulas and compare the results with those from the

ToolPak and from SPSS. As a bonus, the reader will have access

to a worksheet template for the two-way ANOVA that automates

all the calculations required for Module 6, Assignment 2.One-

way ANOVA

The analysis of variance (ANOVA) allows us to compare three

or more means simultaneously, while controlling for the overall

probability of making a Type I error (rejecting a true null

hypothesis). Researchers developed a test to measure

participants’ pain thresholds. The researchers sought to](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/music100-221109044802-b21f41e9/75/Music-100-rtfd1__-email-protected-__button-gif__MACOSX-docx-12-2048.jpg)