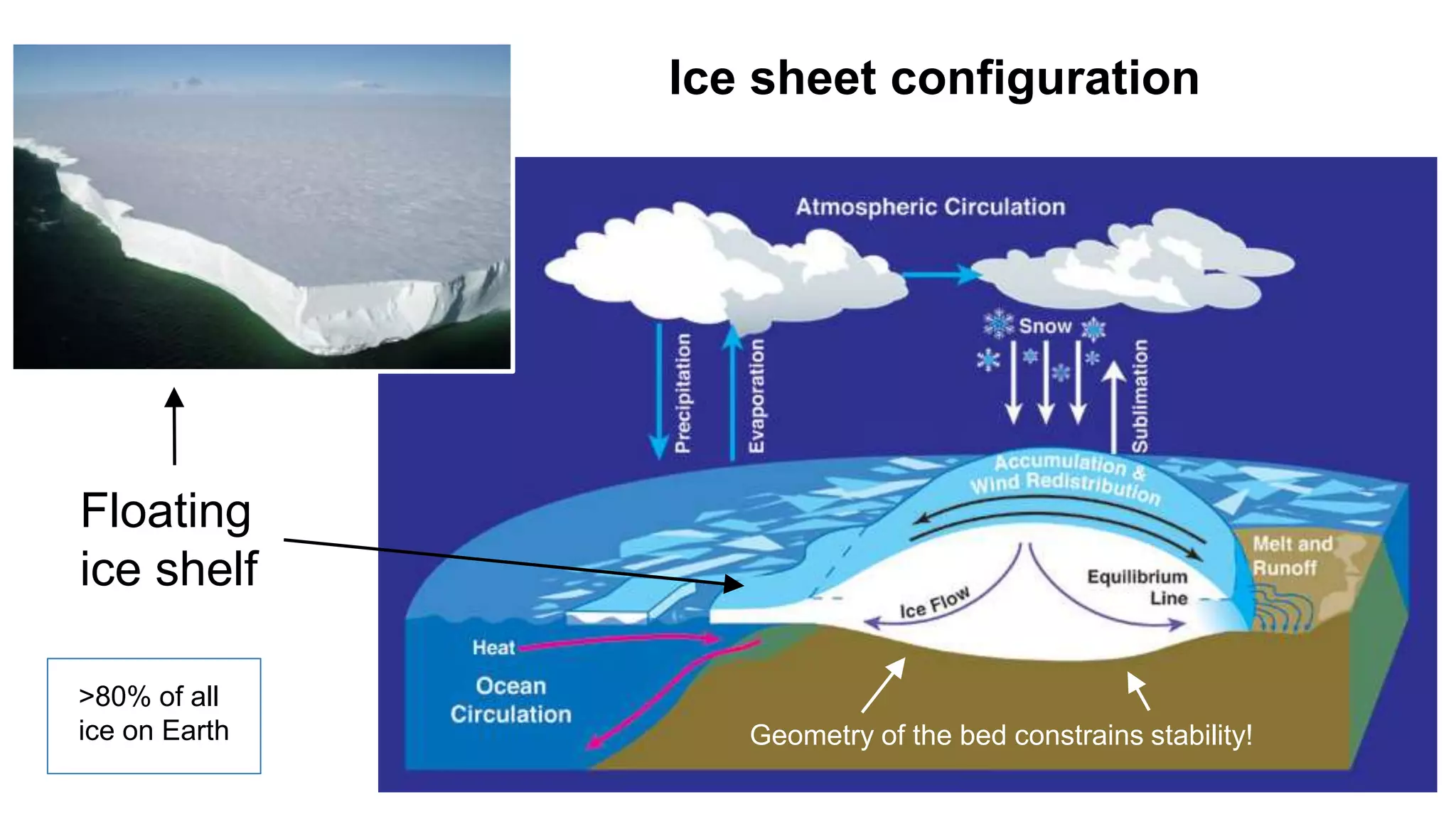

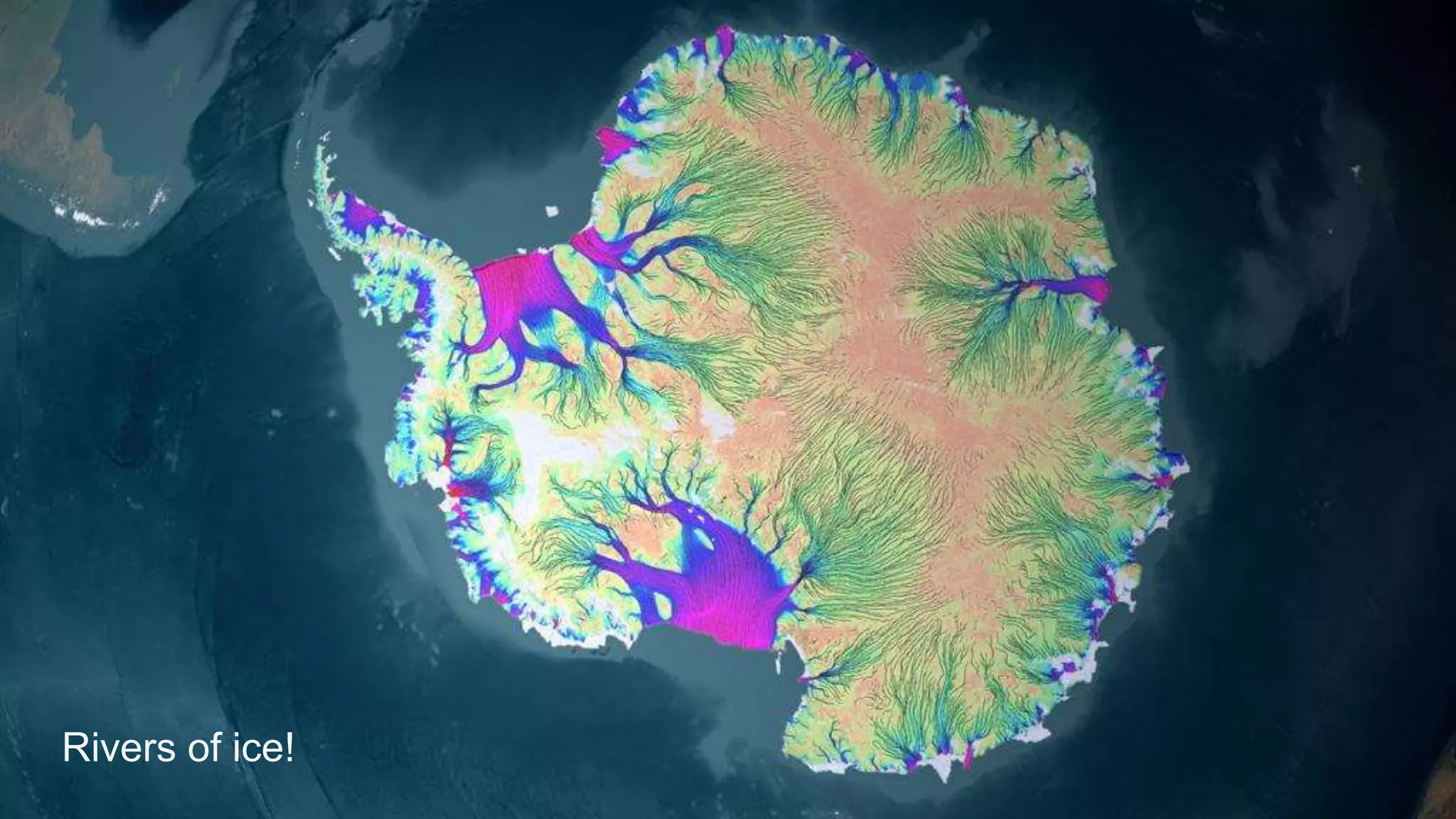

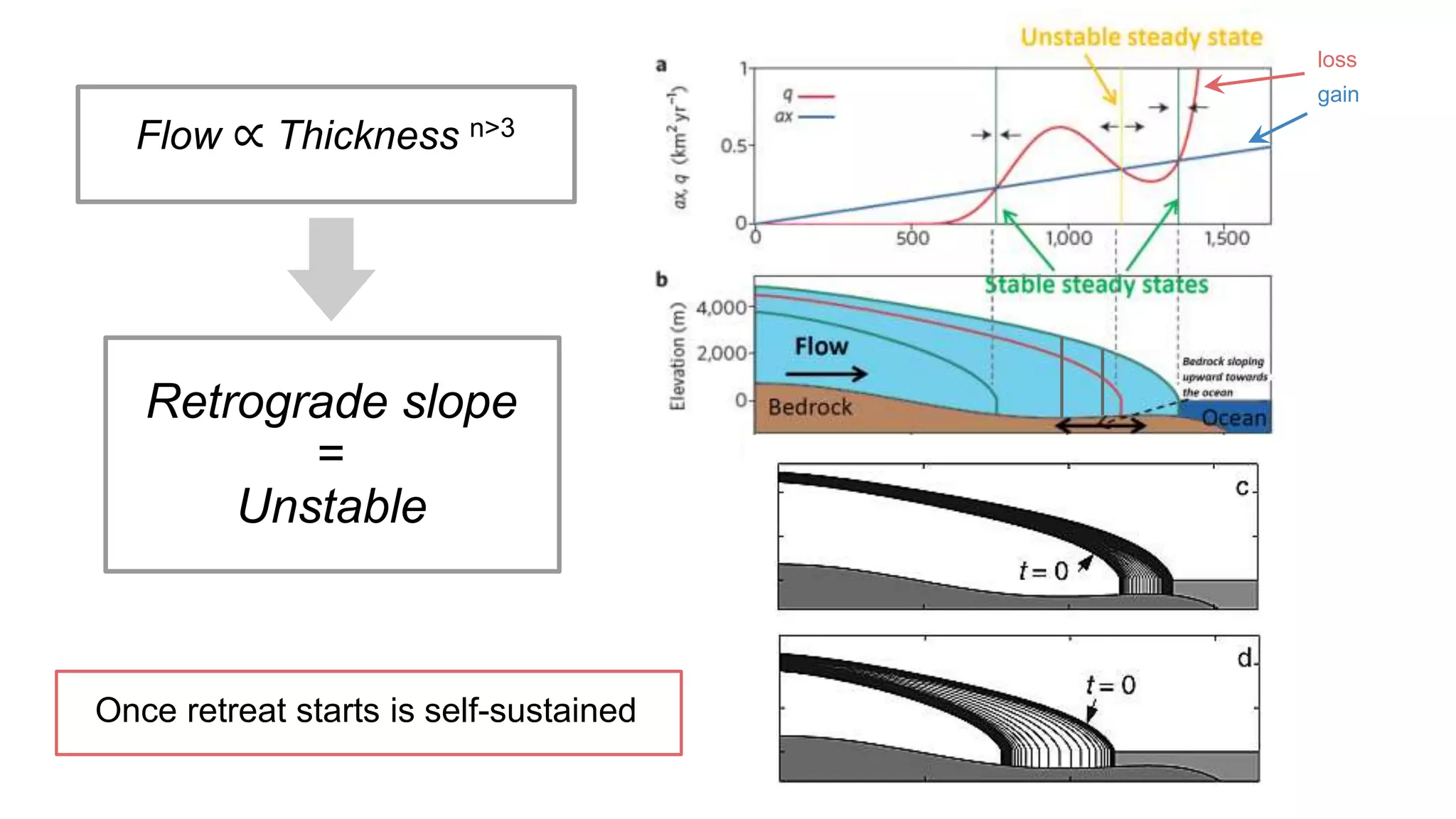

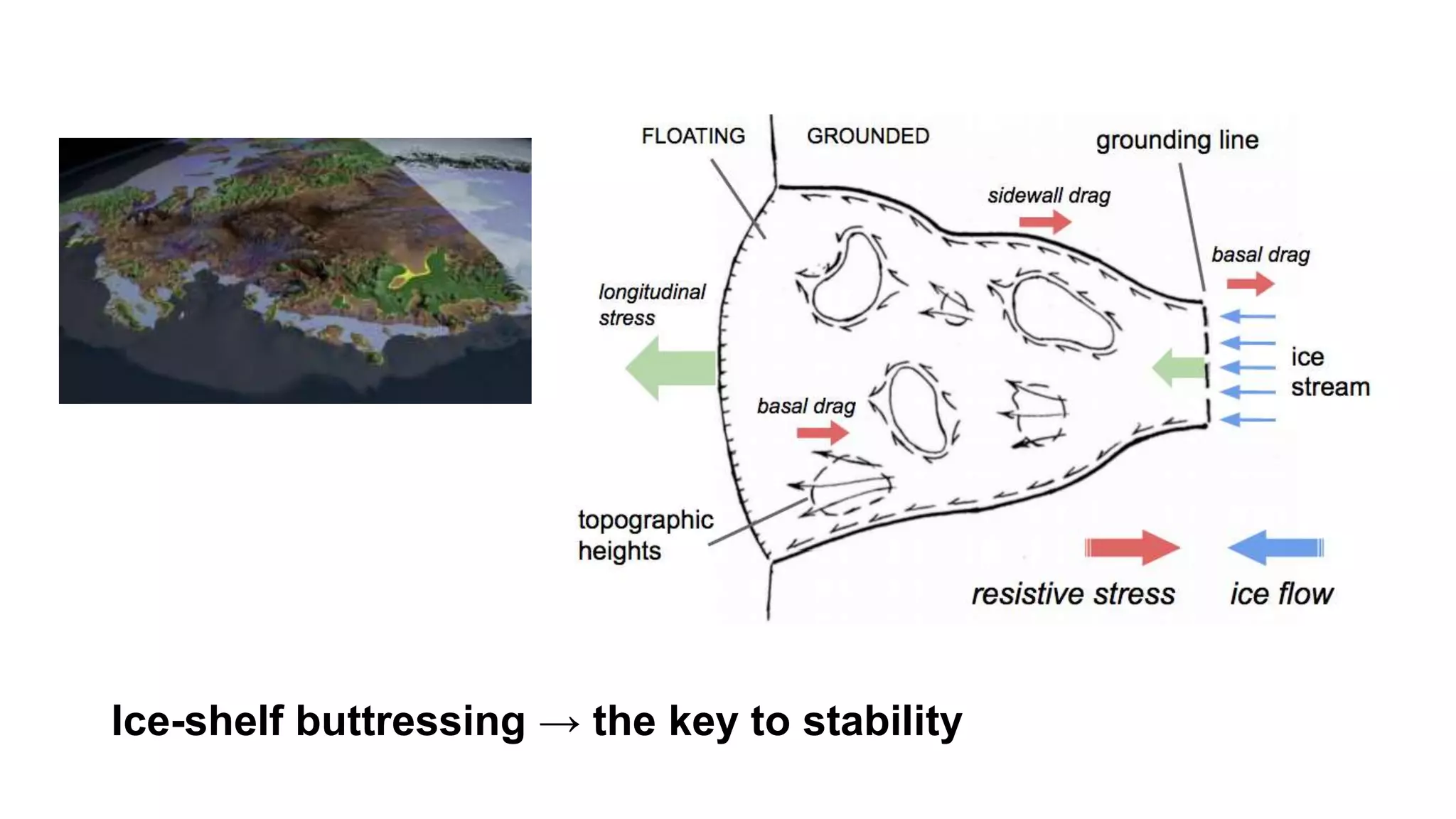

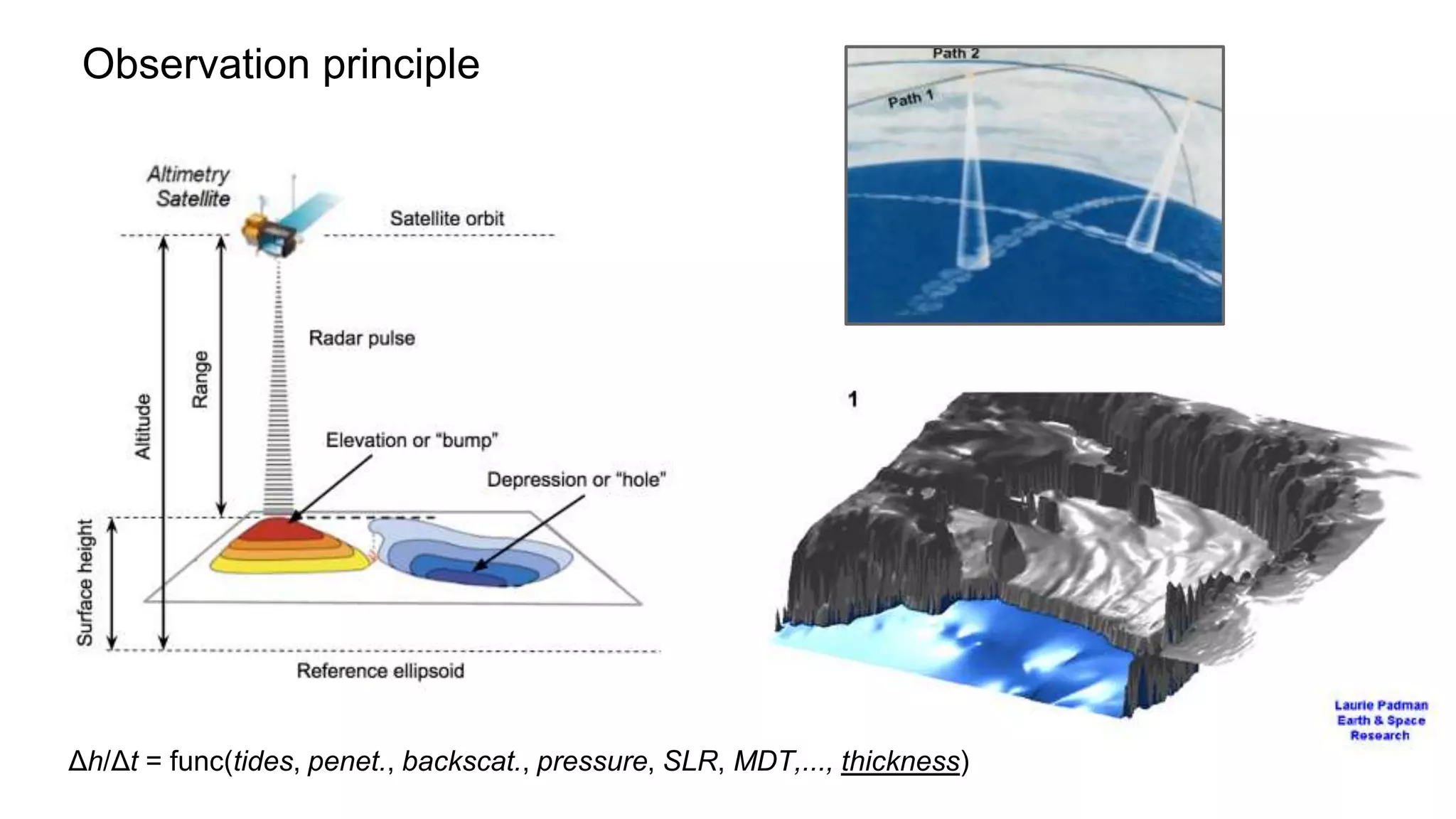

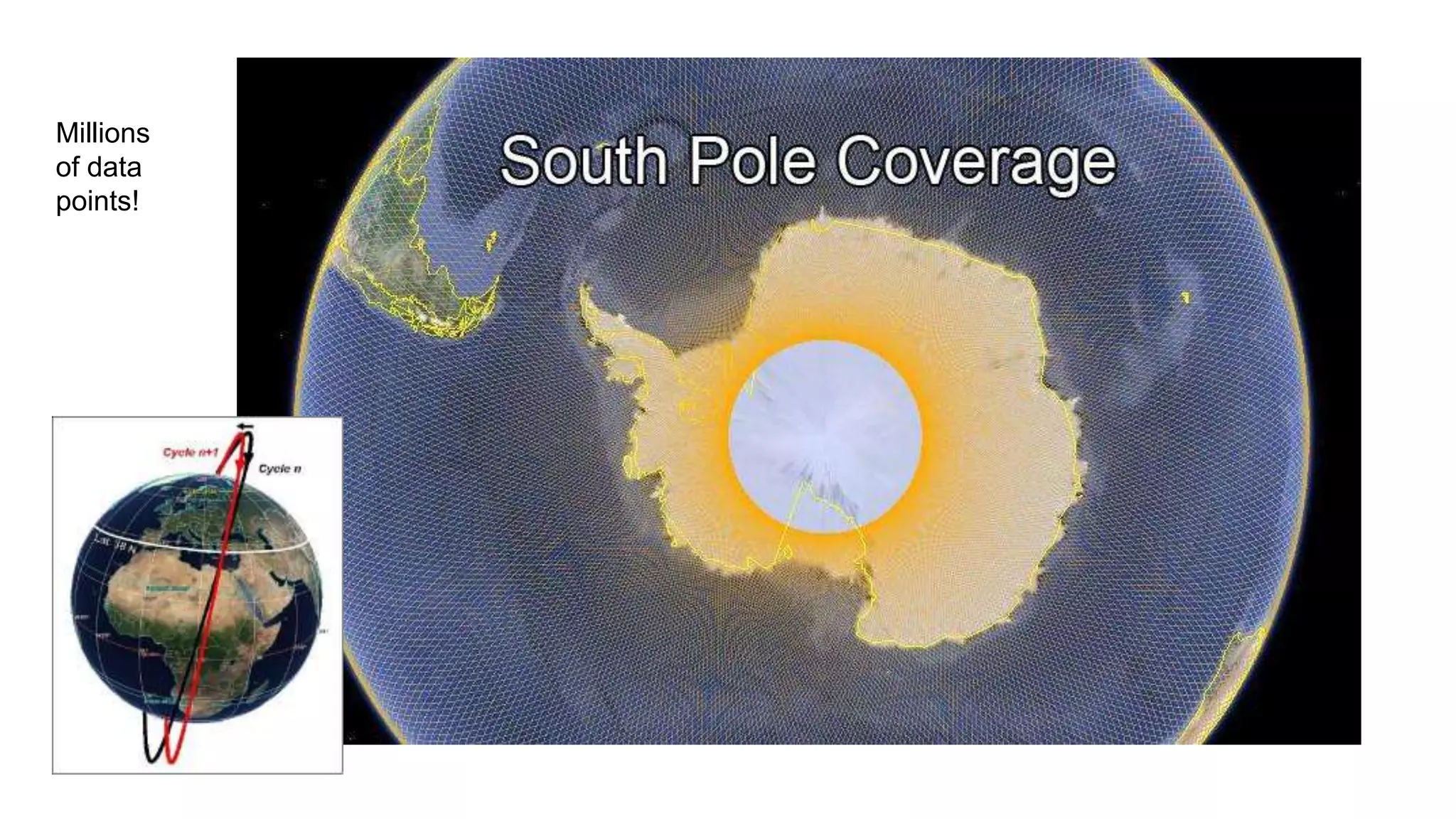

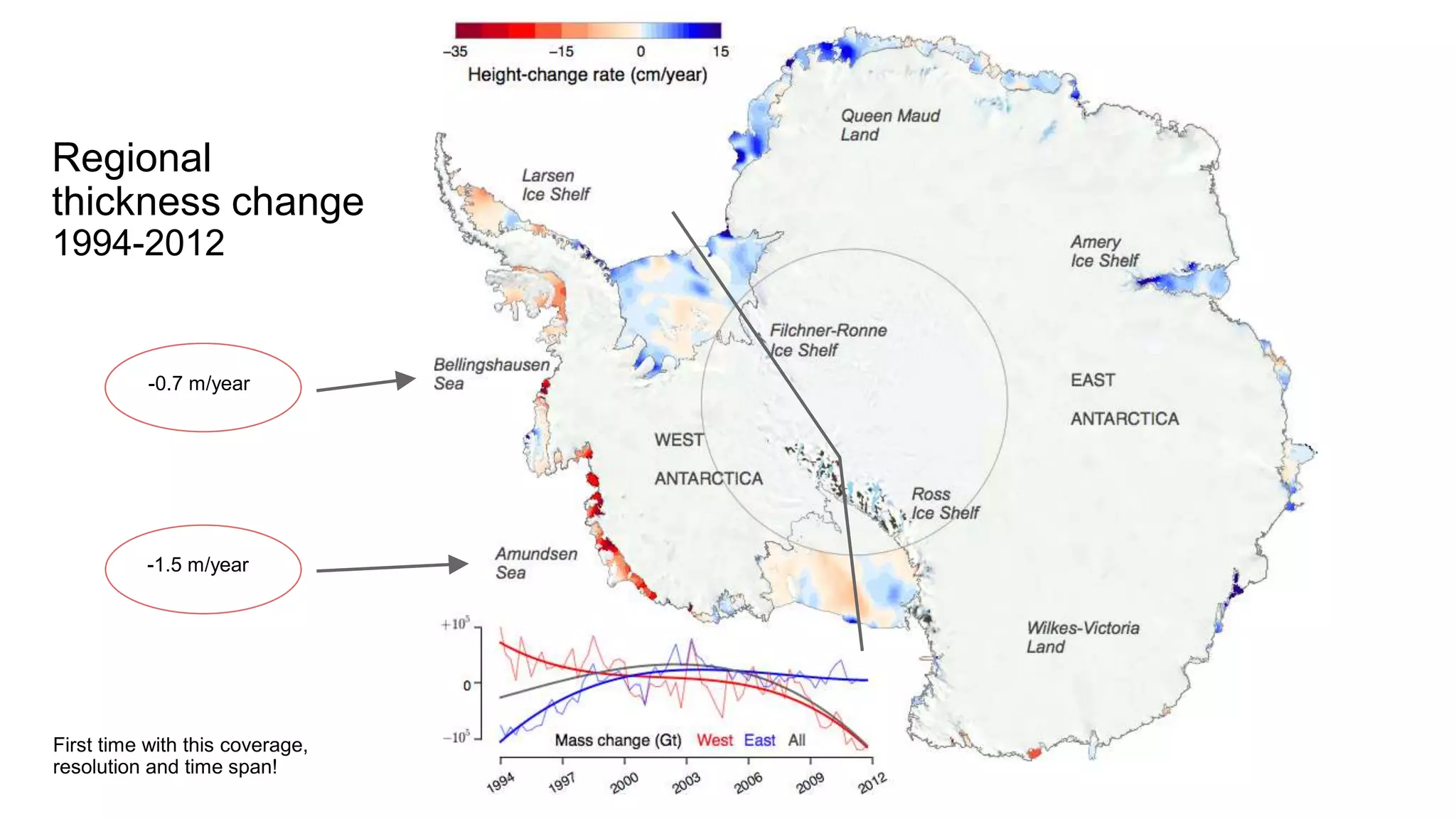

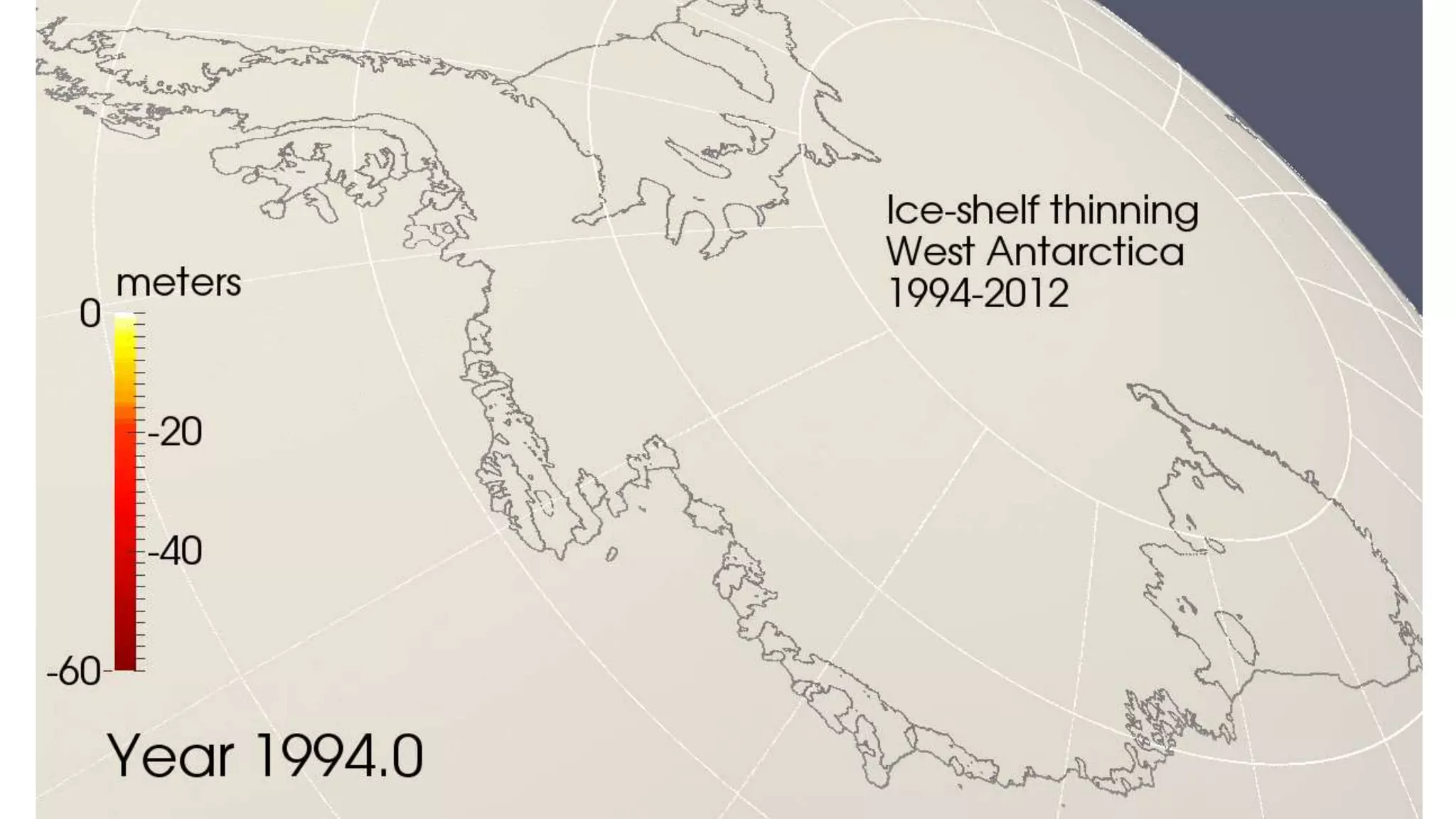

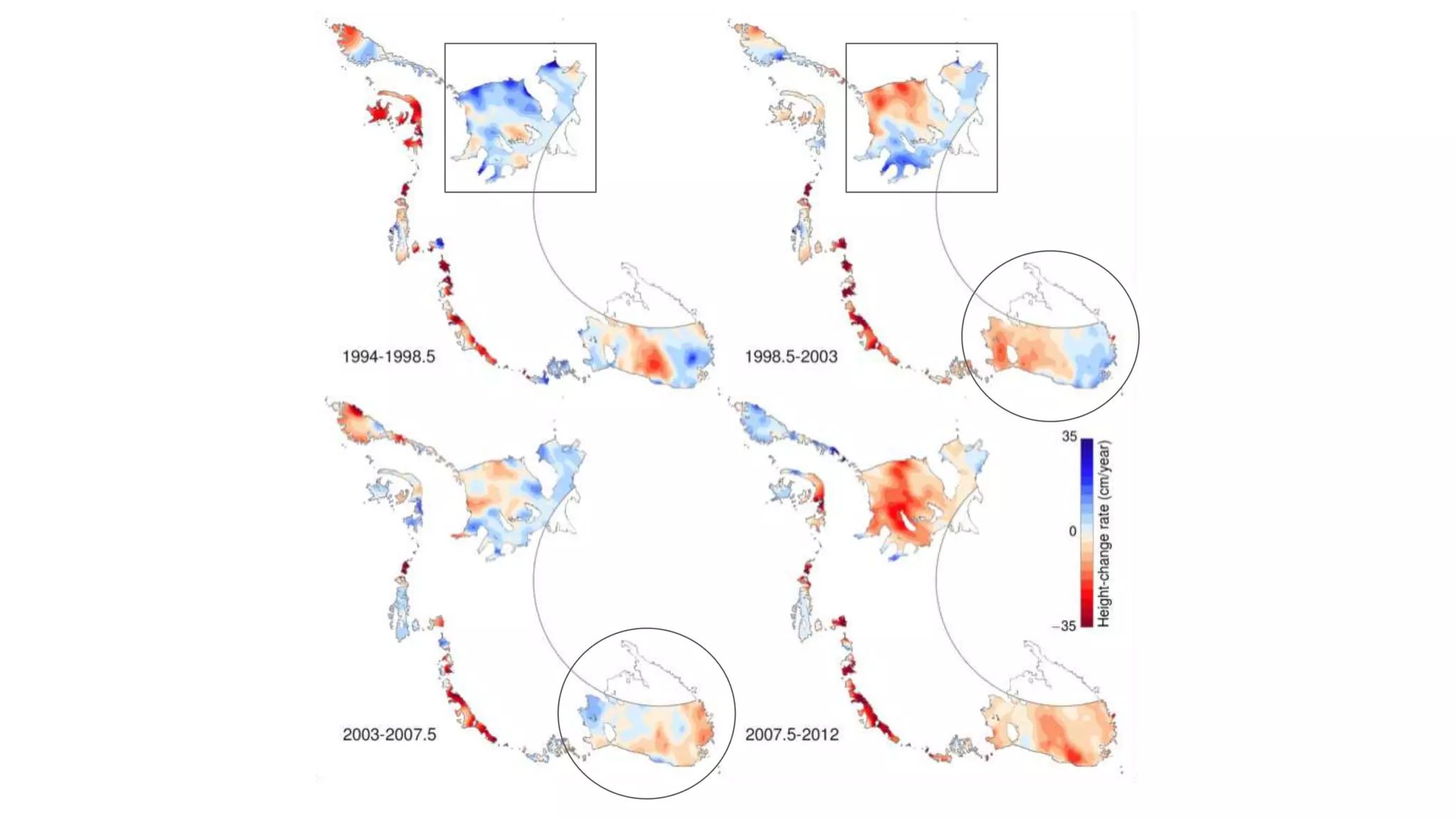

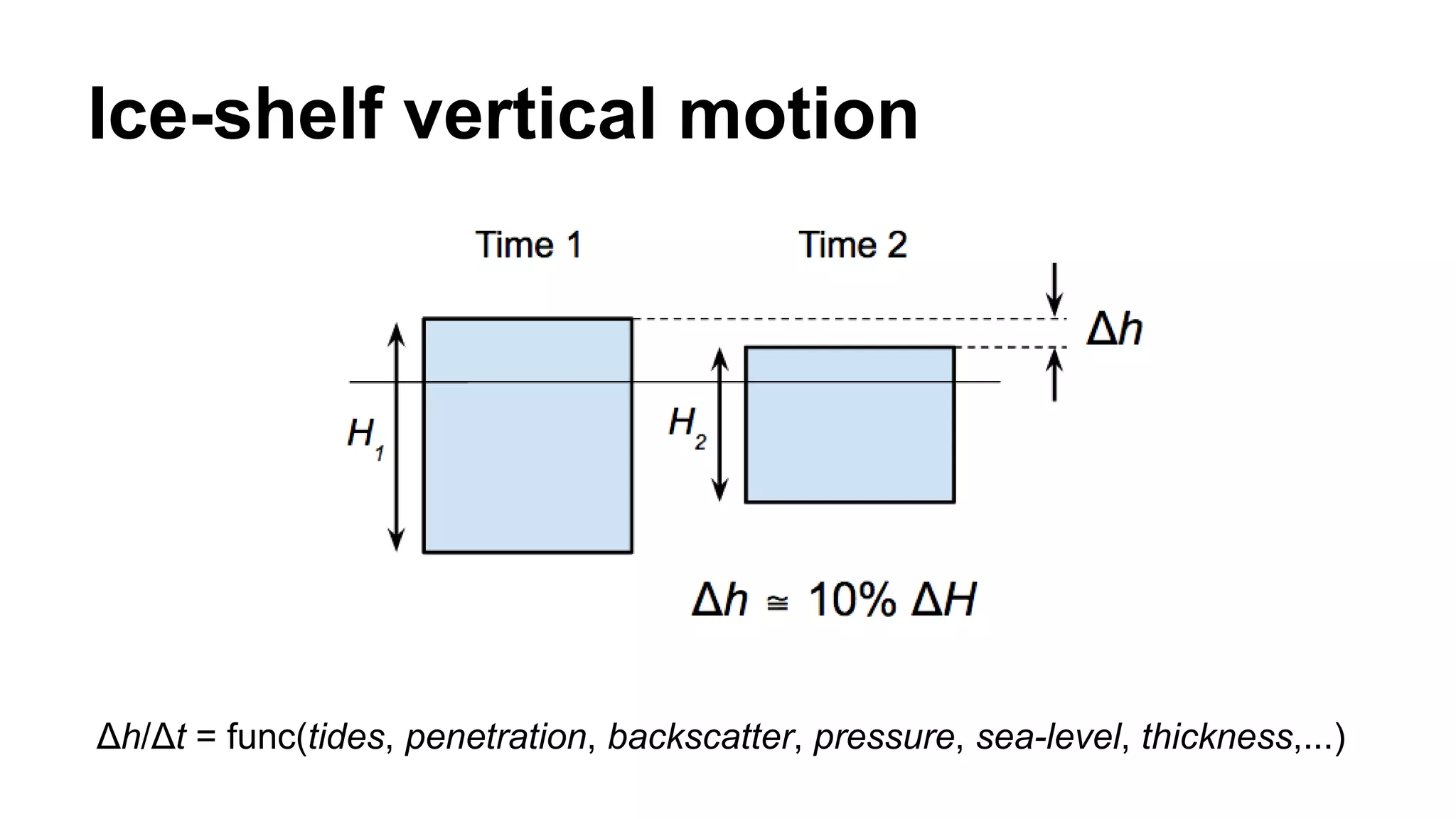

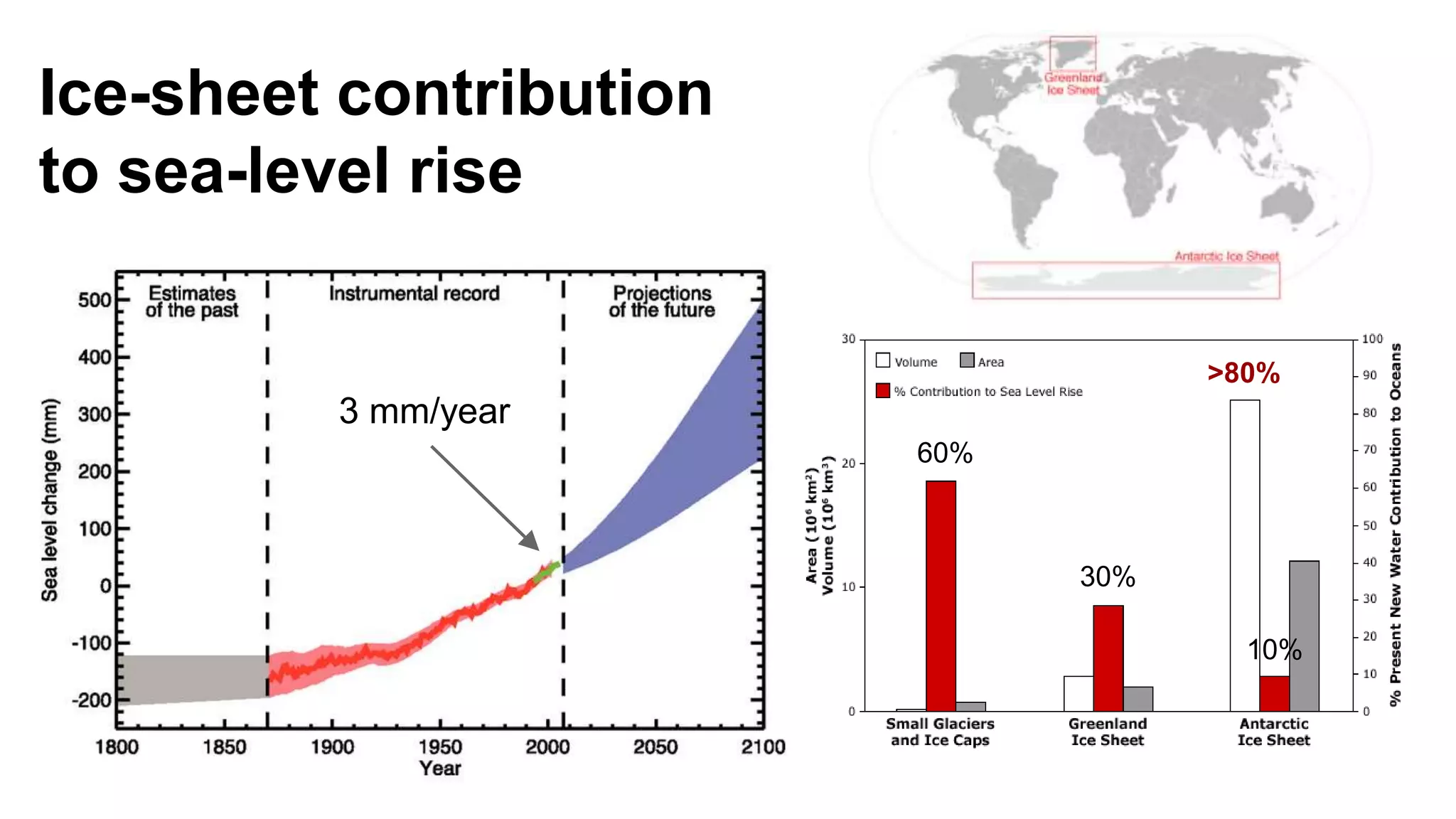

This document summarizes a talk about monitoring ice loss in Antarctica from space. Satellite observations over 18 years show that West Antarctica is losing ice at an accelerated rate of 0.7-1.5 meters per year. The stability of Antarctic ice sheets depends on floating ice shelves, but ocean warming is causing ice shelves to weaken and retreat, leading to increased ice loss from the continent and raising sea levels. Predicting future sea level rise depends on understanding the behavior of Antarctic ice sheets in response to climate change.