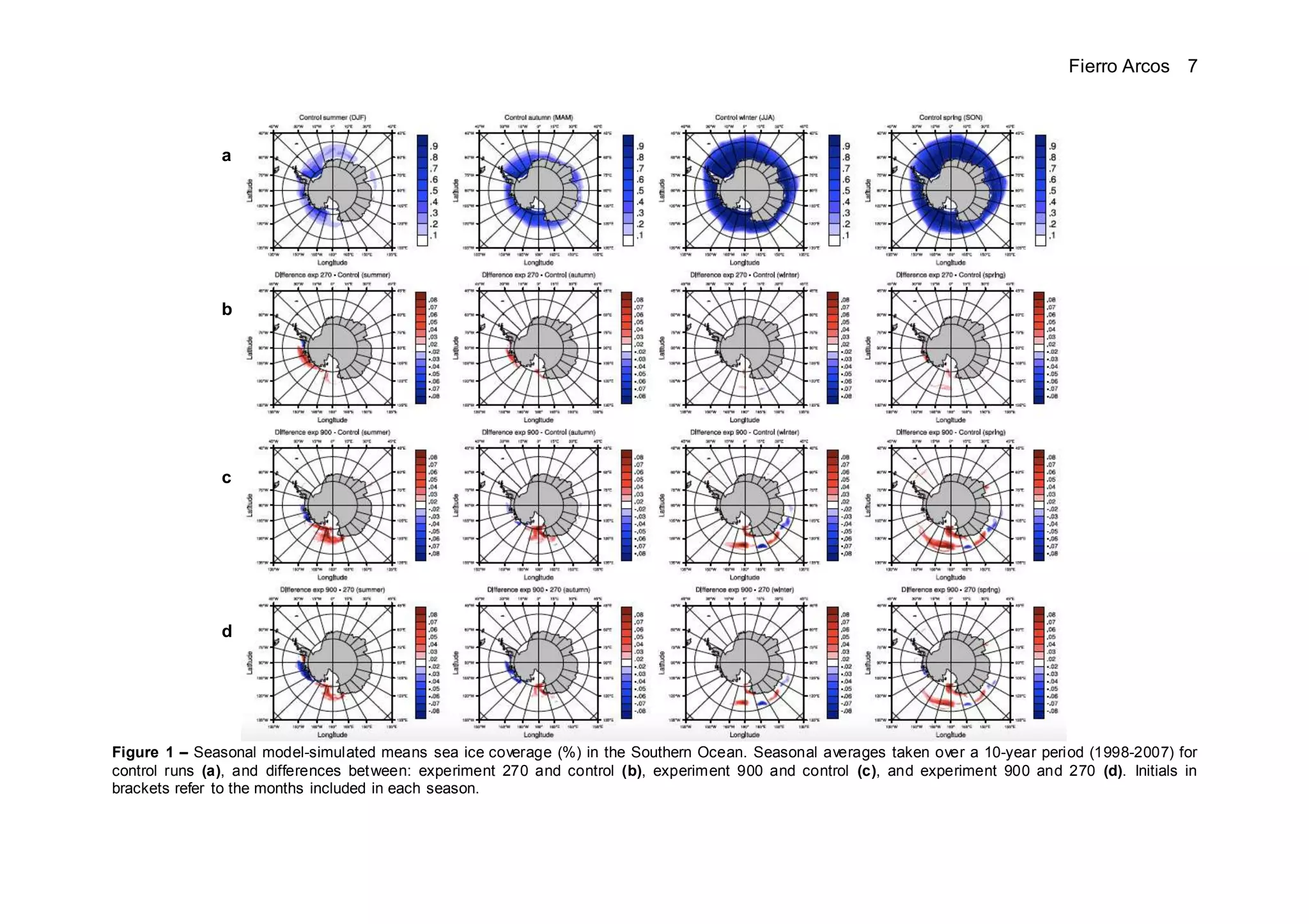

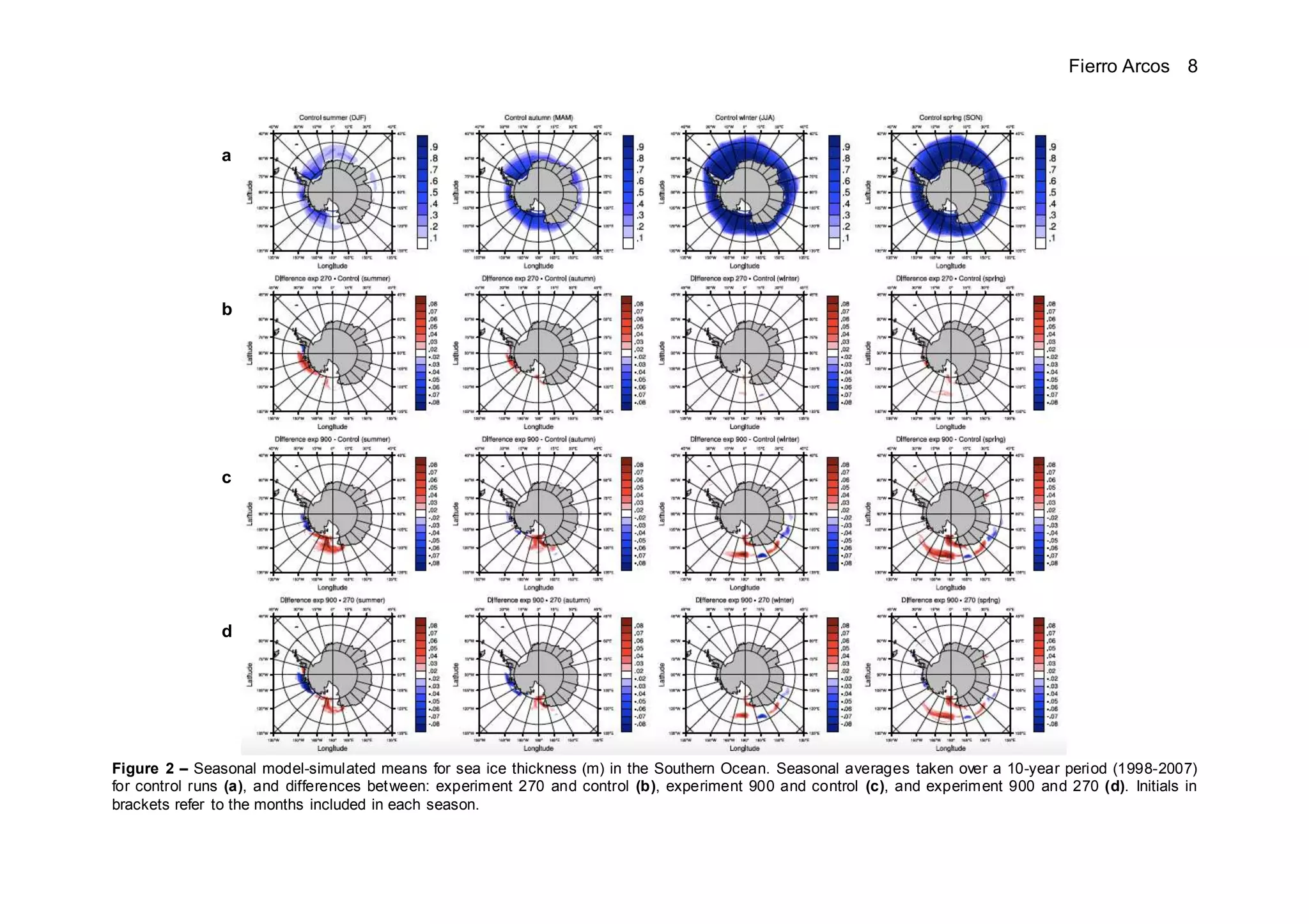

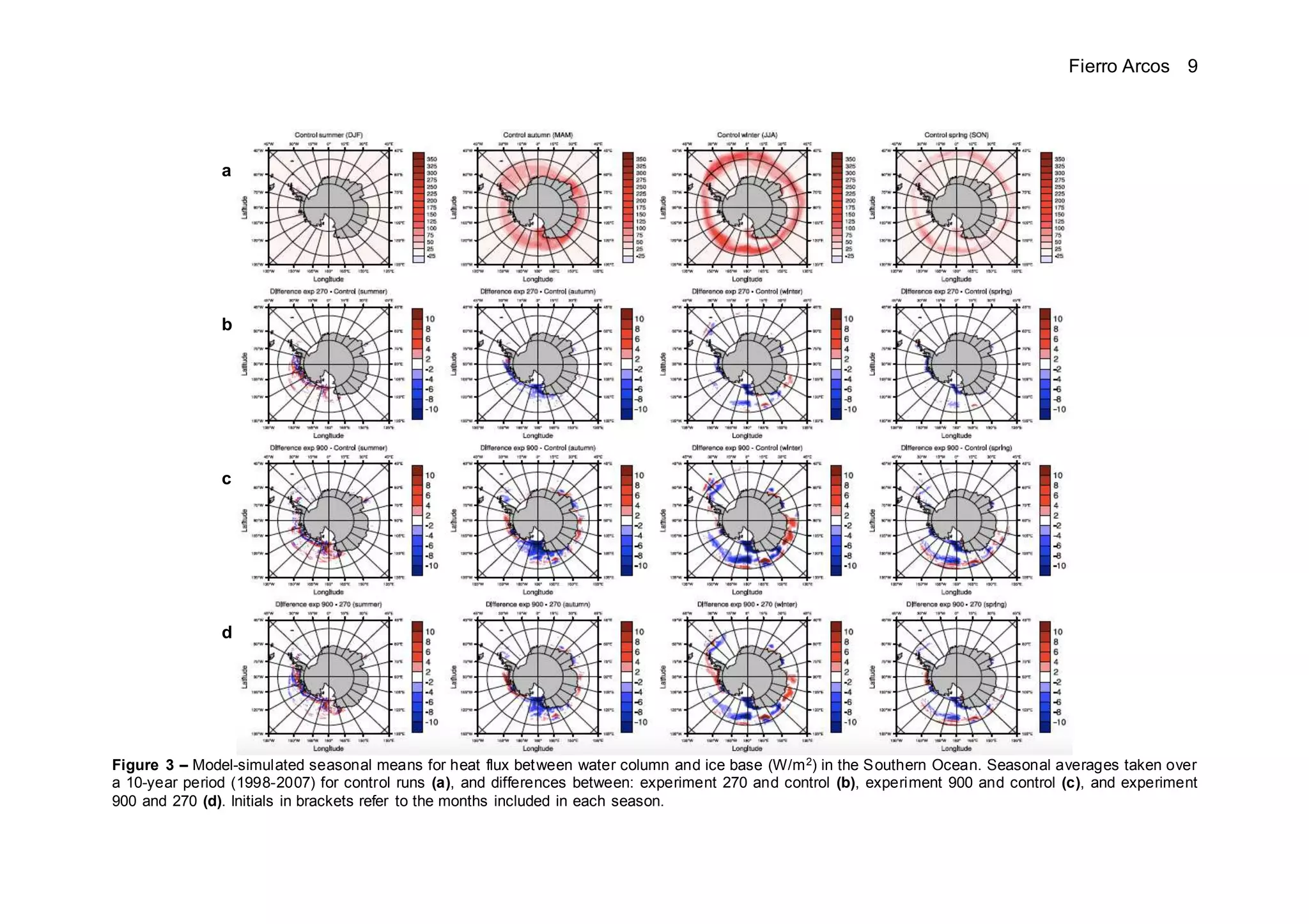

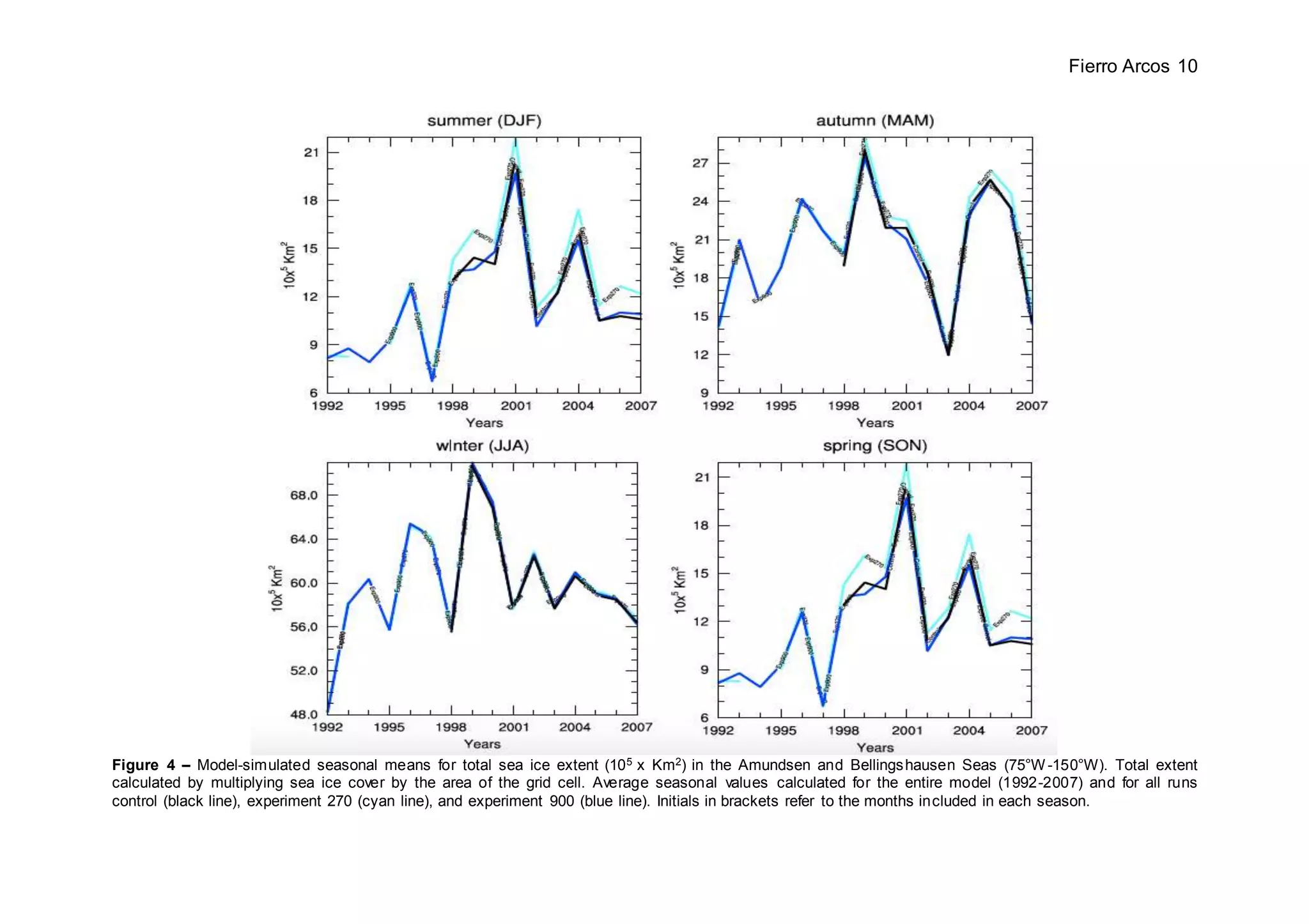

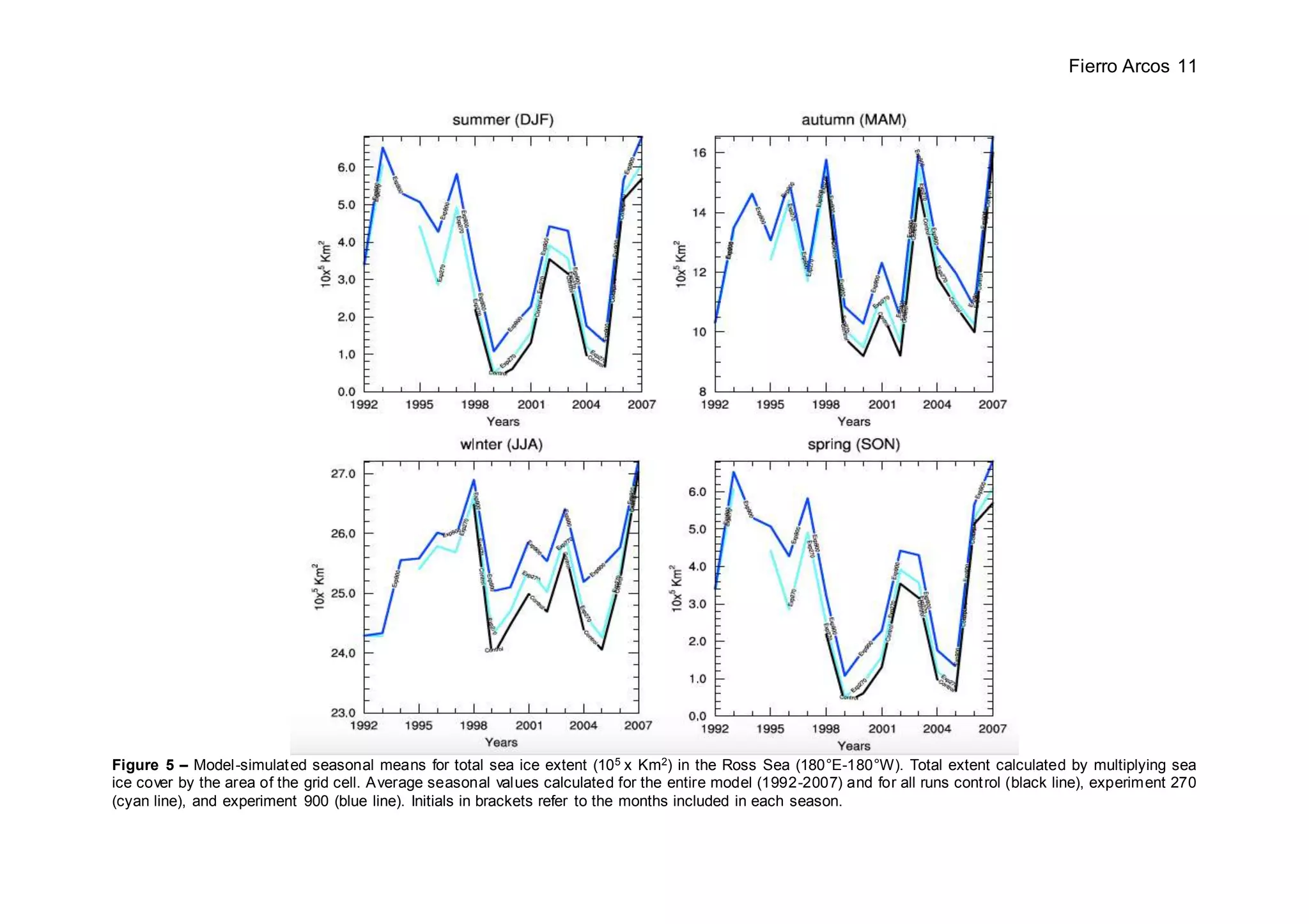

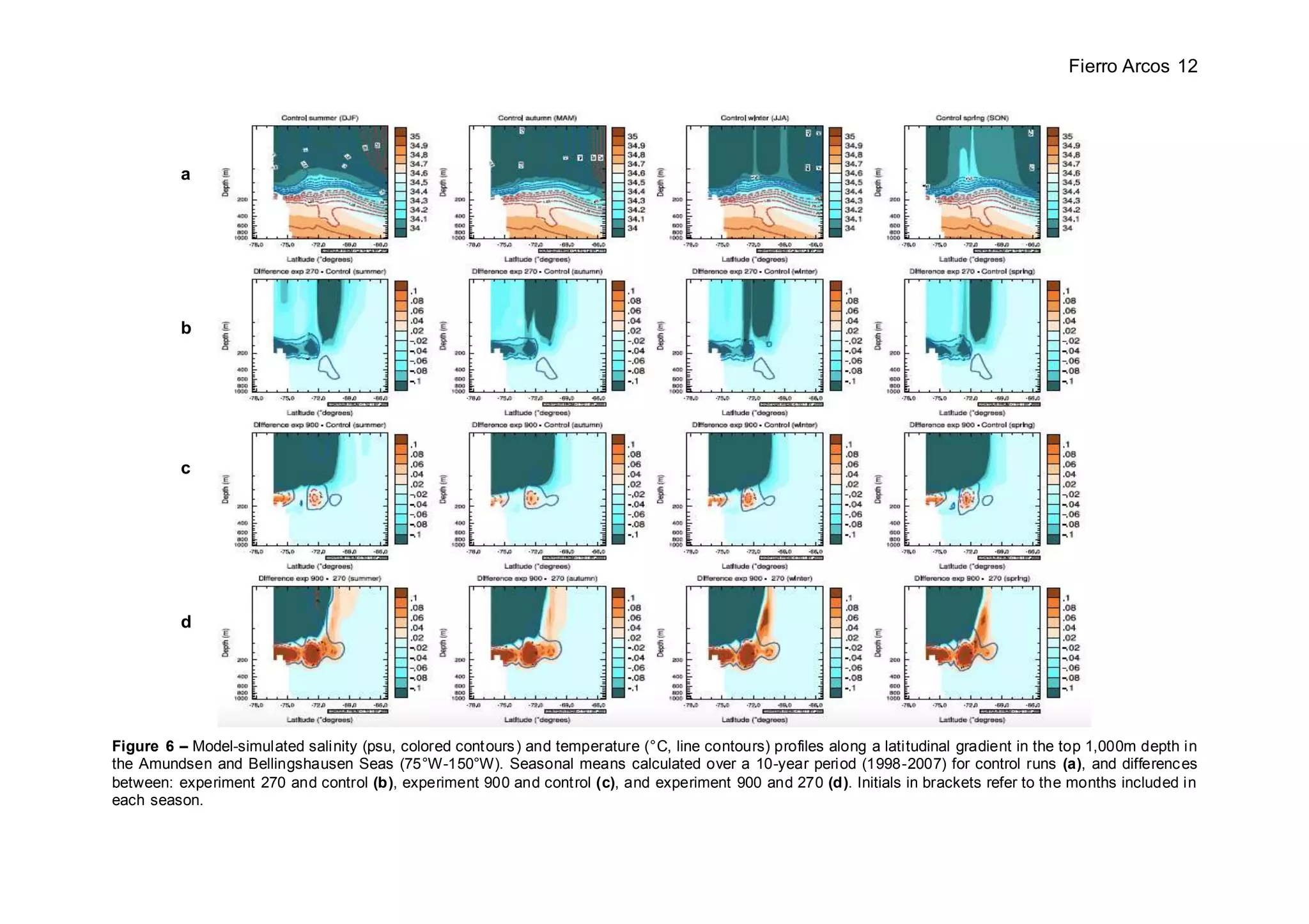

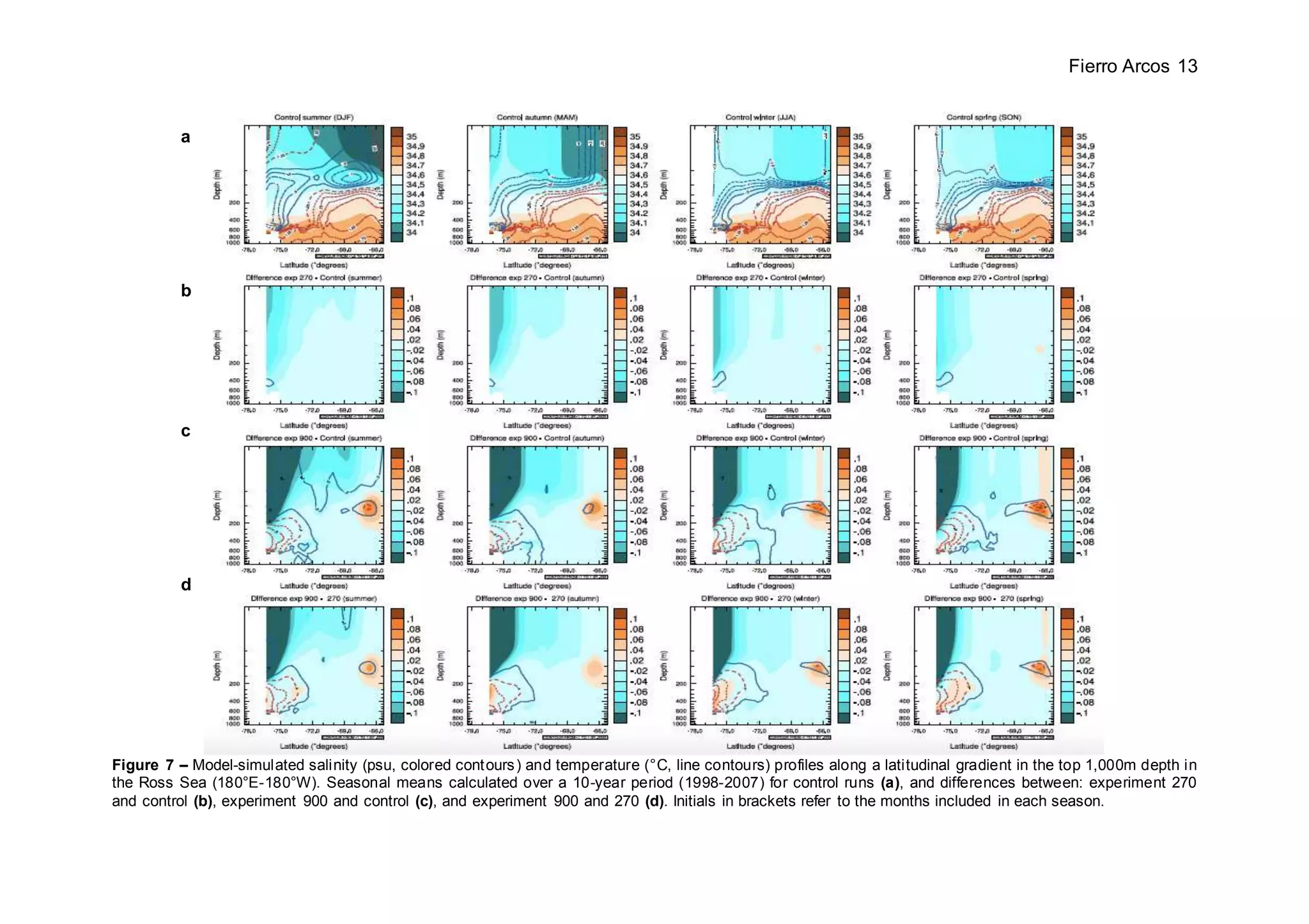

Increased freshwater input from melting ice sheets affects sea ice concentration in the Southern Ocean. A study analyzed output from an ocean circulation model under different freshwater flux scenarios. Adding more freshwater led to increased sea ice coverage and thickness in the Ross Sea, but decreases in the Amundsen and Bellingshausen Seas. Higher freshwater flux caused freshening and cooling of surface waters near Antarctica, making conditions more favorable for sea ice growth in some areas but less in others due to changing ocean temperatures and salinities.

![Fierro Arcos 6

References

BINTANJA, R., OLDENBORGH, G. J. V., DRIJFHOUT, S. S., WOUTERS, B. &

KATSMAN, C. A. 2013. Important role for ocean warming and increased ice-

shelf melt in Antarctic sea-ice expansion. Nature Geoscience, 6, 376-379.

HELLMER, H. H. 2004. Impact of Antarctic ice shelf basal melting on sea ice and

deep ocean properties. Geophysical Research Letters, 31, L10307.

RIGNOT, E. & JACOBS, S. S. 2002. Rapid Bottom Melting Widespread near

Antarctic Ice Sheet Grounding Lines. Science, 296, 2020-2023.

RYE, C. D., NAVEIRA-GARABATO, A. C., HOLLAND, P. R., MEREDITH, M. P.,

NURSER, A. J. G., HUGHES, C. W., COWARD, A. C. & WEBB, D. J. 2014.

Rapid sea-level rise along the Antarctic margins in response to increased

glacial discharge. Nature Geoscience, 7, 732-735.

SCOTT, M. 2009. Sea Ice [Online]. NASA - EOS Project Science Office. Available:

http://earthobservatory.nasa.gov/Features/SeaIce/ [Accessed February 17th

2016].](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/d05d773e-09eb-4bc5-a728-74095f66e89d-160228044437/75/Final-Report-6-2048.jpg)