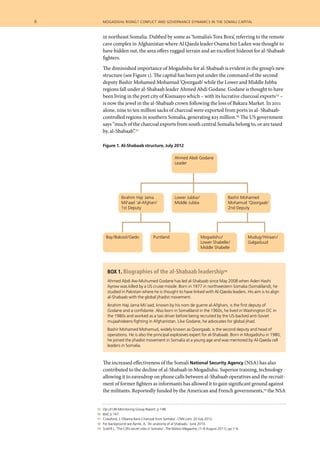

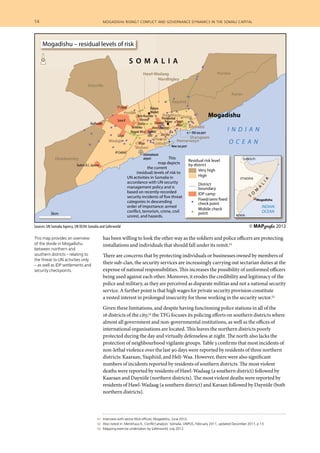

The document provides an overview of the conflict and governance dynamics in Mogadishu, Somalia as of August 2012. It finds that while security has improved due to al-Shabaab fighters withdrawing from the city, security remains inadequate with significant unpoliced areas. Criminal violence and private militias filling the security gap are ongoing challenges. Land disputes and the dominance of the president's clan in the capital are sources of potential unrest. External actors are seen as disproportionately influencing the political transition, and concerns are growing about foreign commercial dealings concentrating on a narrow group of elites.