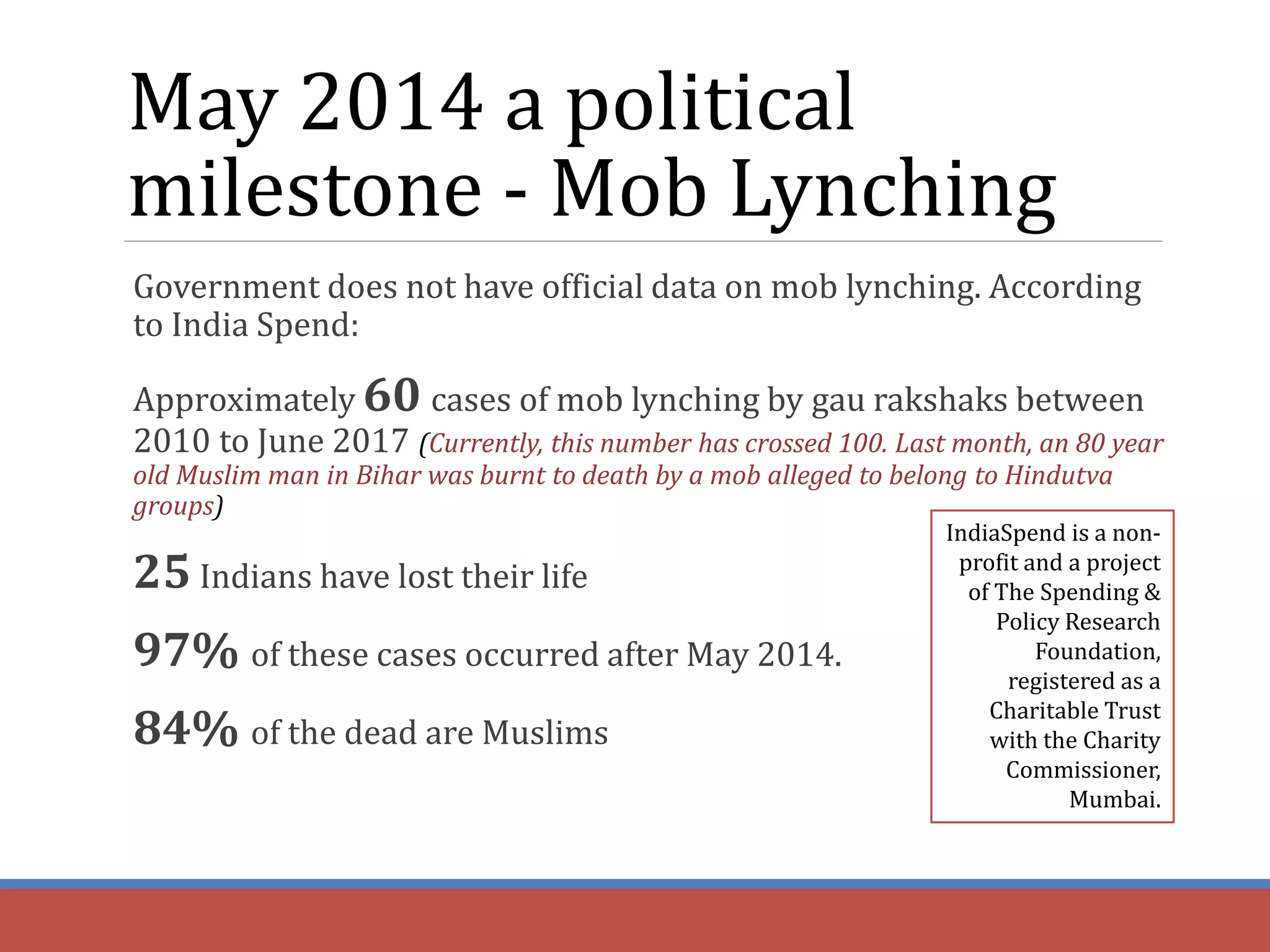

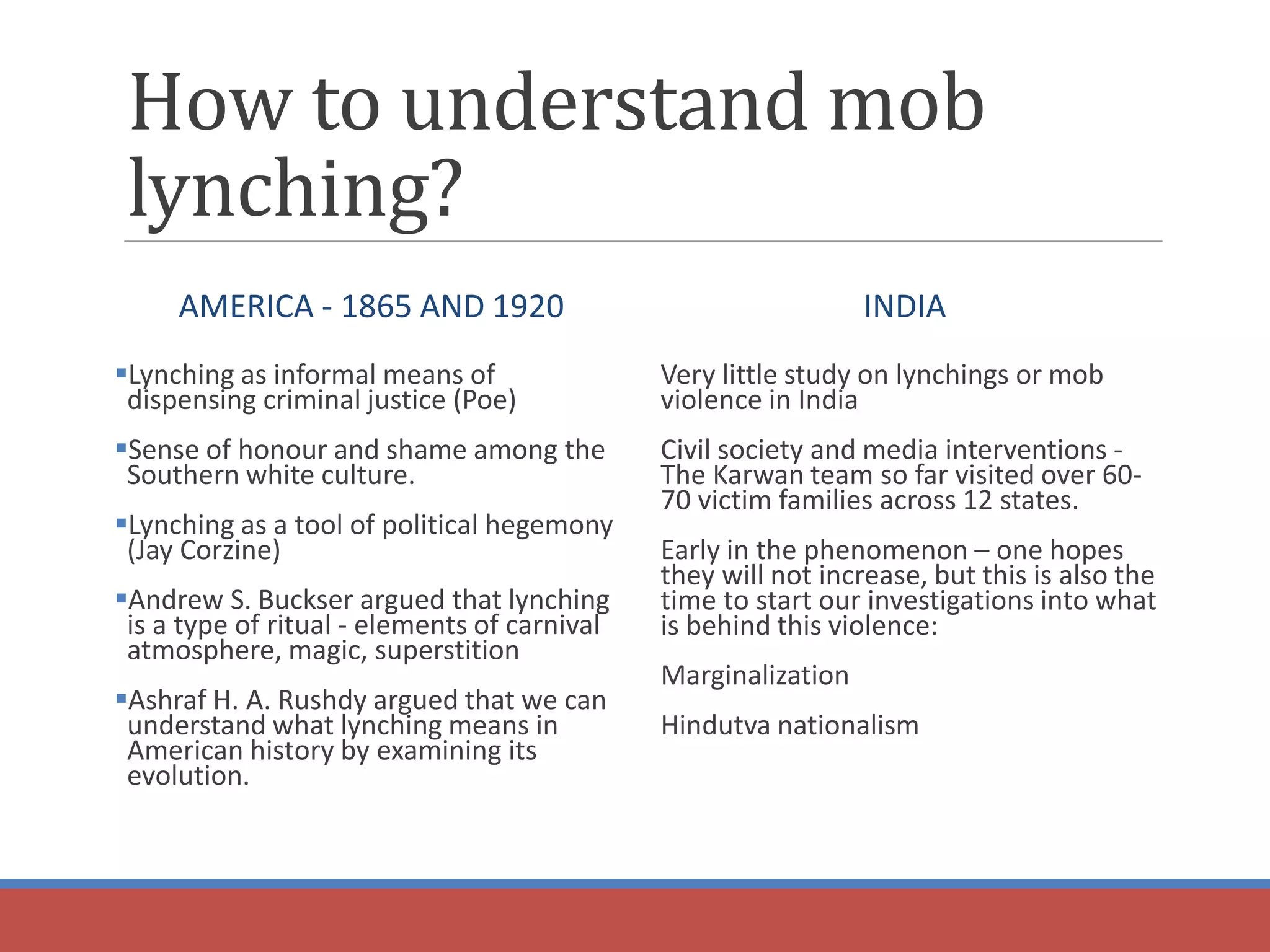

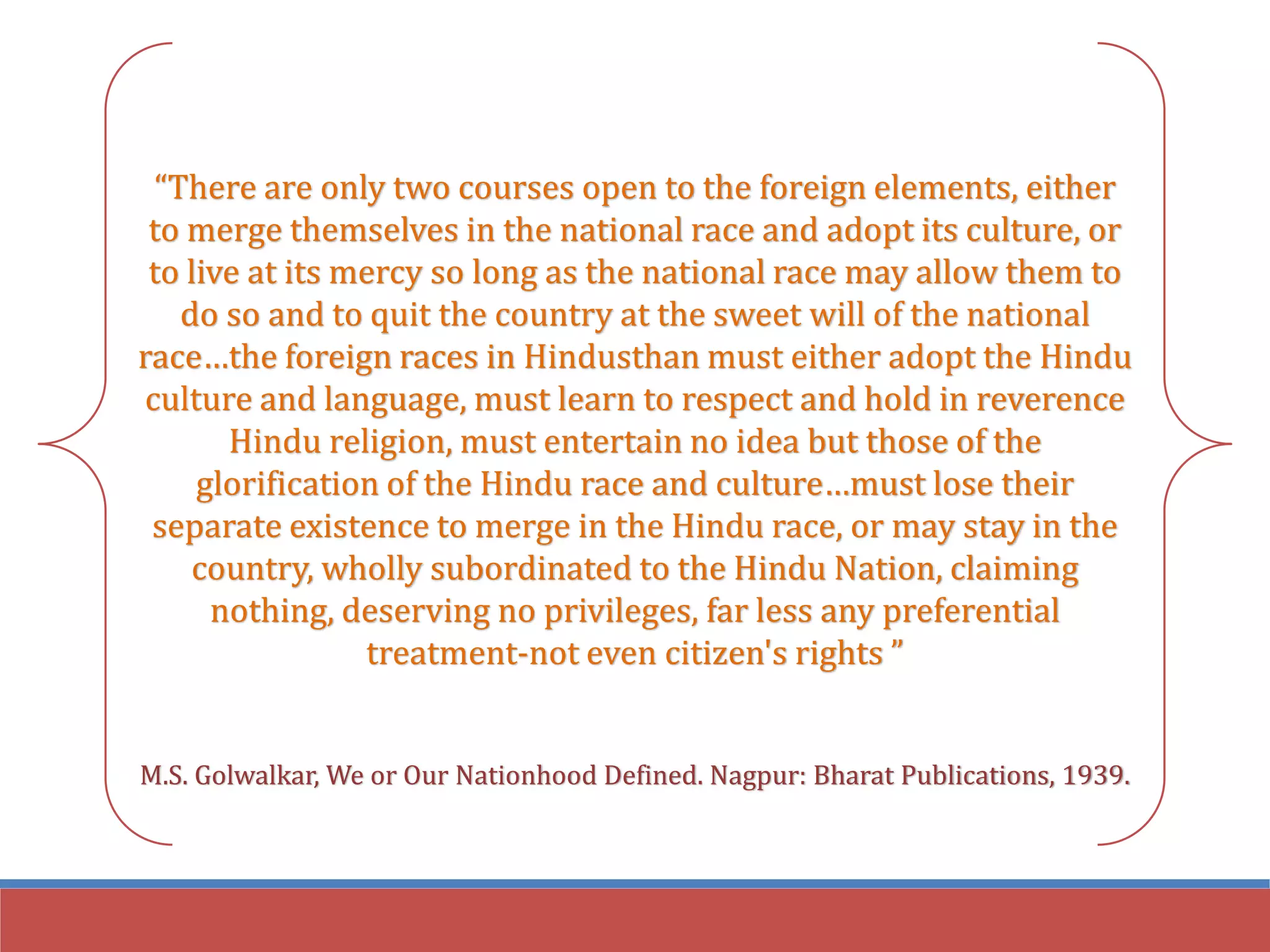

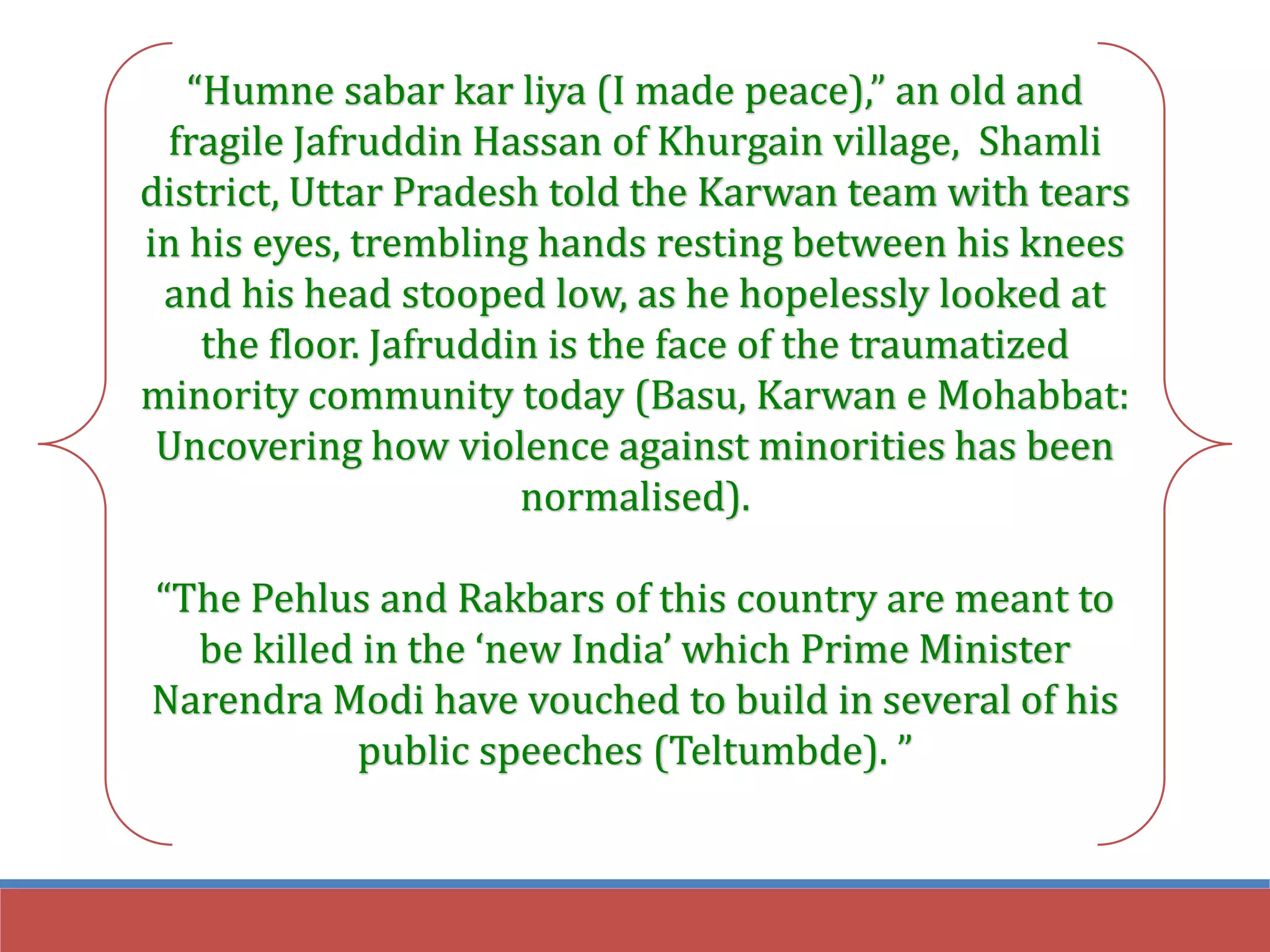

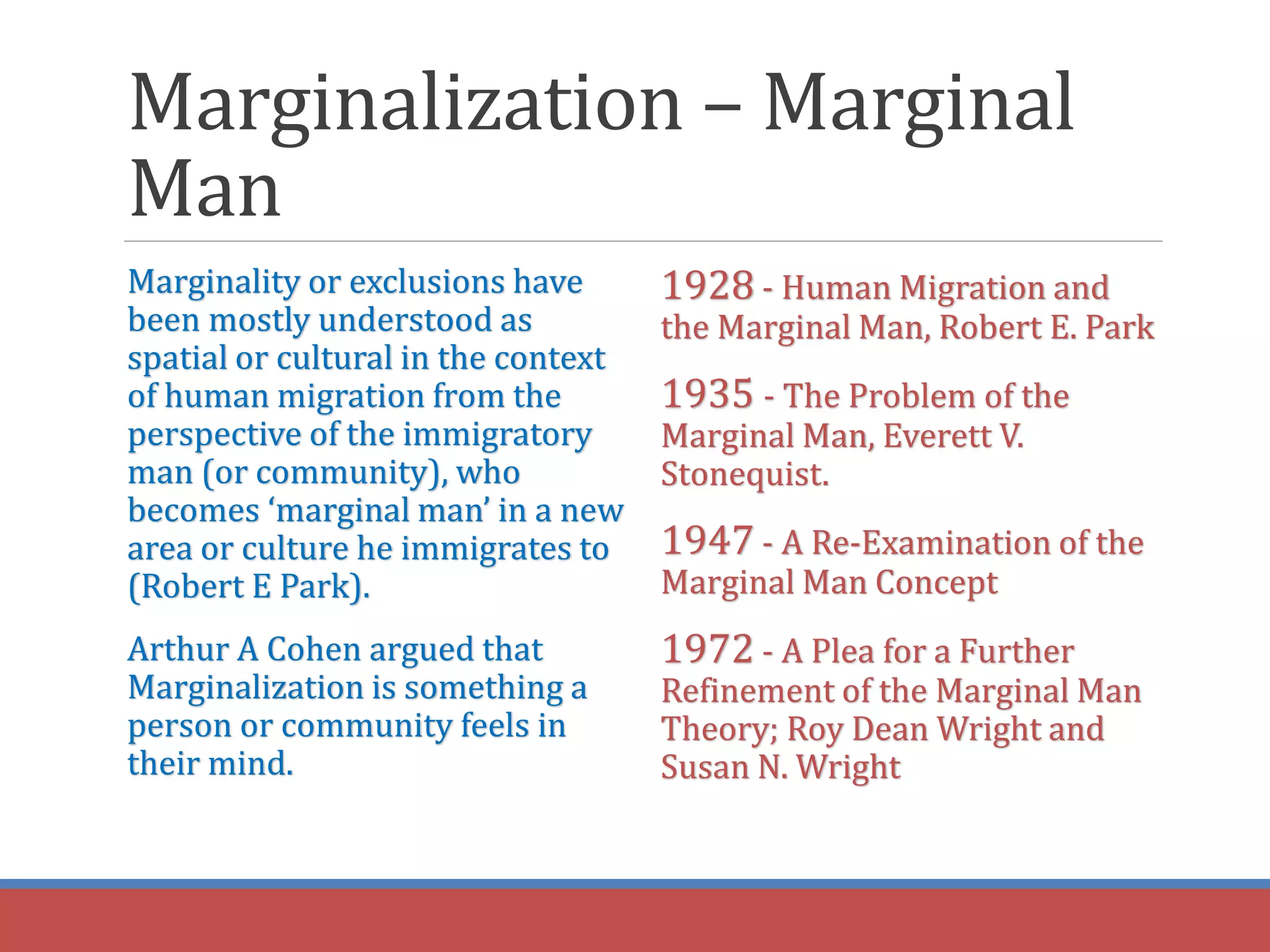

This document discusses mob lynching in India and the everyday lives and marginalization of women. It provides background information on mob lynching cases since 2010 according to IndiaSpend data. It then discusses the specifics of one high-profile case in 2015. The document explores how to understand mob lynching through historical and social science frameworks. It argues that marginalization in India's context cannot be understood through migration-based theories and must consider the exclusion of Muslims from Indian nationalism. The document also notes the need to consider marginalization within marginalized communities, including the experiences of women, in order to have a more complete understanding of issues like mob lynching.