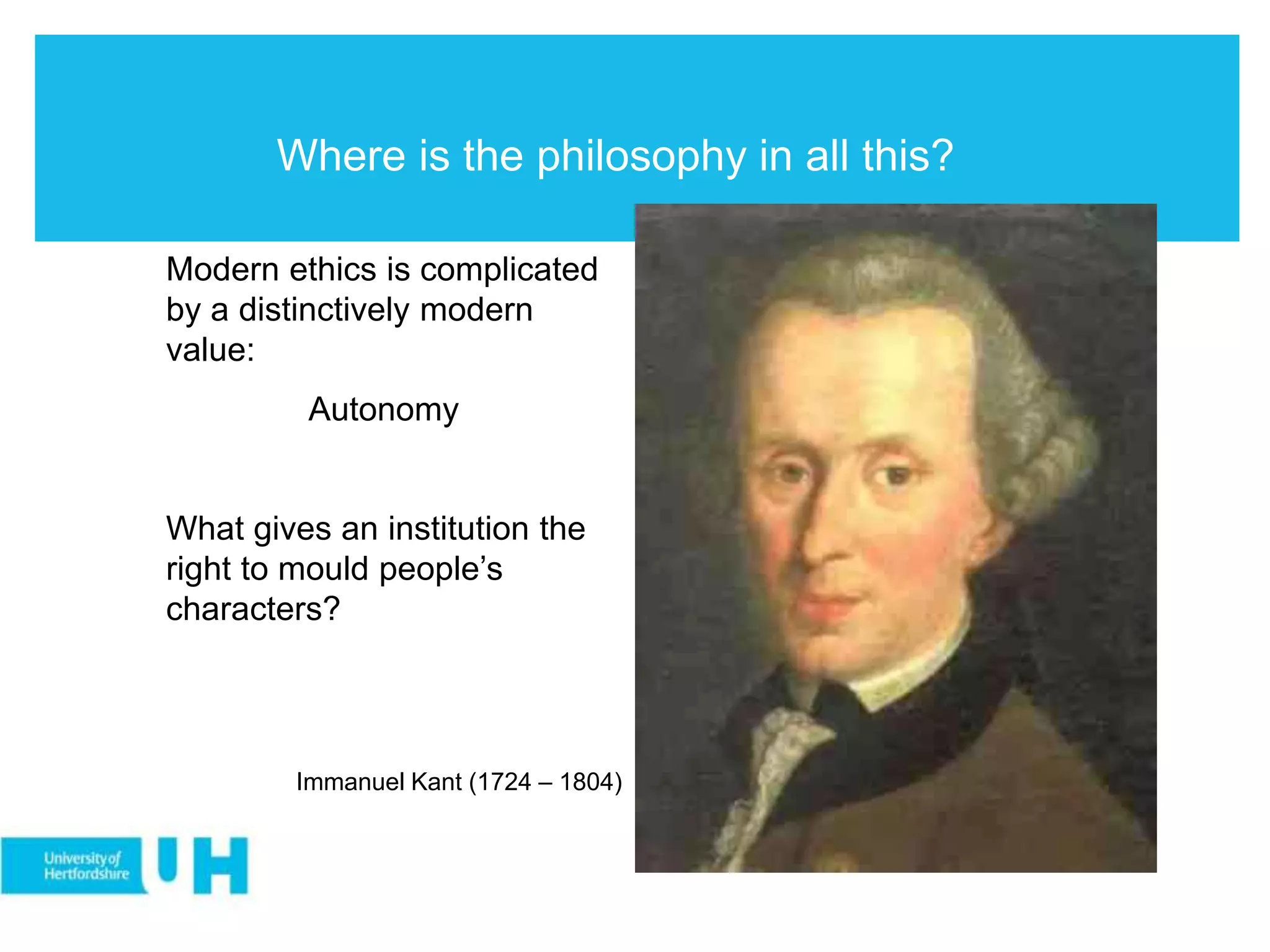

This document summarizes a philosophy mini-conference timetable and presentations. The first presentation by Drs. Brendan Larvor and John Lippitt discusses what kind of students universities want, focusing on sociable and curious students with virtues like teamwork, humility, and forgiveness. The second presentation by Dr. Craig Bourne considers whether it is permissible for parents to choose disabilities for their children, discussing two cases: 1) Amish parents limiting their children's education, and 2) parents choosing disabilities for their future children. The final presentation is on seeing one's own brain without surgery.

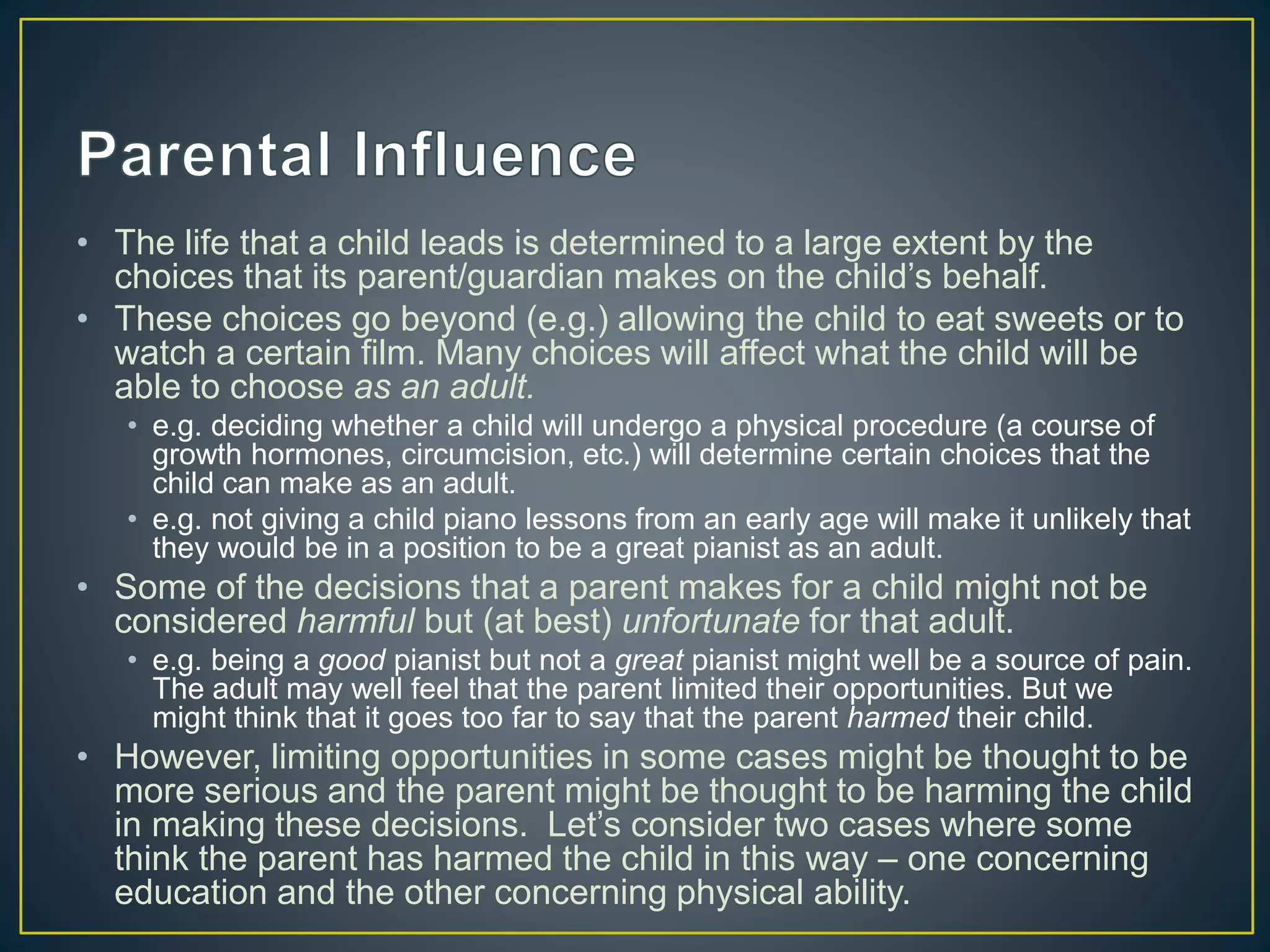

![Joel Feinberg (1980) ‘The Child’s Right to an Open

Future’, writes about this case (Wisconsin v. Yoder,

1972):

‘The aim of Amish education is to prepare the young

for a life of industry and piety by transmitting to them

the unchanged farming and household methods of

their ancestors and a thorough distrust of modern

techniques and styles … [T]he Amish have always

tried their best to insulate their communities from

external influences … Their own schools teach only

enough reading to make a lifetime of Bible study

possible, only enough arithmetic to permit the keeping

of budget books and records of simple commercial

transactions. Four or five years of this, plus exercises

in sociality, devotional instruction, inculcation of

traditional virtues, and on-the-job training in simple

crafts of field, shop, or kitchen are all that is required,

in a formal way, to prepare children for the traditional

Amish way of life to which their parents are bound by

the most solemn commitments.’](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/mini-conference20201420final20bp-190605173804/75/Mini-conference-2014-final-24-2048.jpg)

![‘Amish [parents] … had been convicted of violating …

compulsory school attendance law (which requires

attendance until the age of sixteen) by refusing to

send their children to … school after they had

graduated from the eighth grade. The Court

acknowledged that the case required a balancing of

legitimate interests …

…but concluded that the interest of the parents in

determining the religious upbringing of their children

out-weighed the claim of the state … “to extend the

benefit of secondary education to children regardless

of the wishes of their parents.”’

Questions:

Which interests are in conflict? Which are more important to protect?

Have the parents deprived their children by limiting the options the

child could choose for its future (e.g. going to university)?

Is it more important to preserve the existence of different ways of

life?

From whose point of view should we judge which options are](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/mini-conference20201420final20bp-190605173804/75/Mini-conference-2014-final-25-2048.jpg)