1. Mechanical waves are disturbances that propagate through a medium, causing the particles of the medium to vibrate about their equilibrium positions without transporting matter.

2. Transverse waves have displacements perpendicular to the direction of propagation, while longitudinal waves have displacements parallel to propagation.

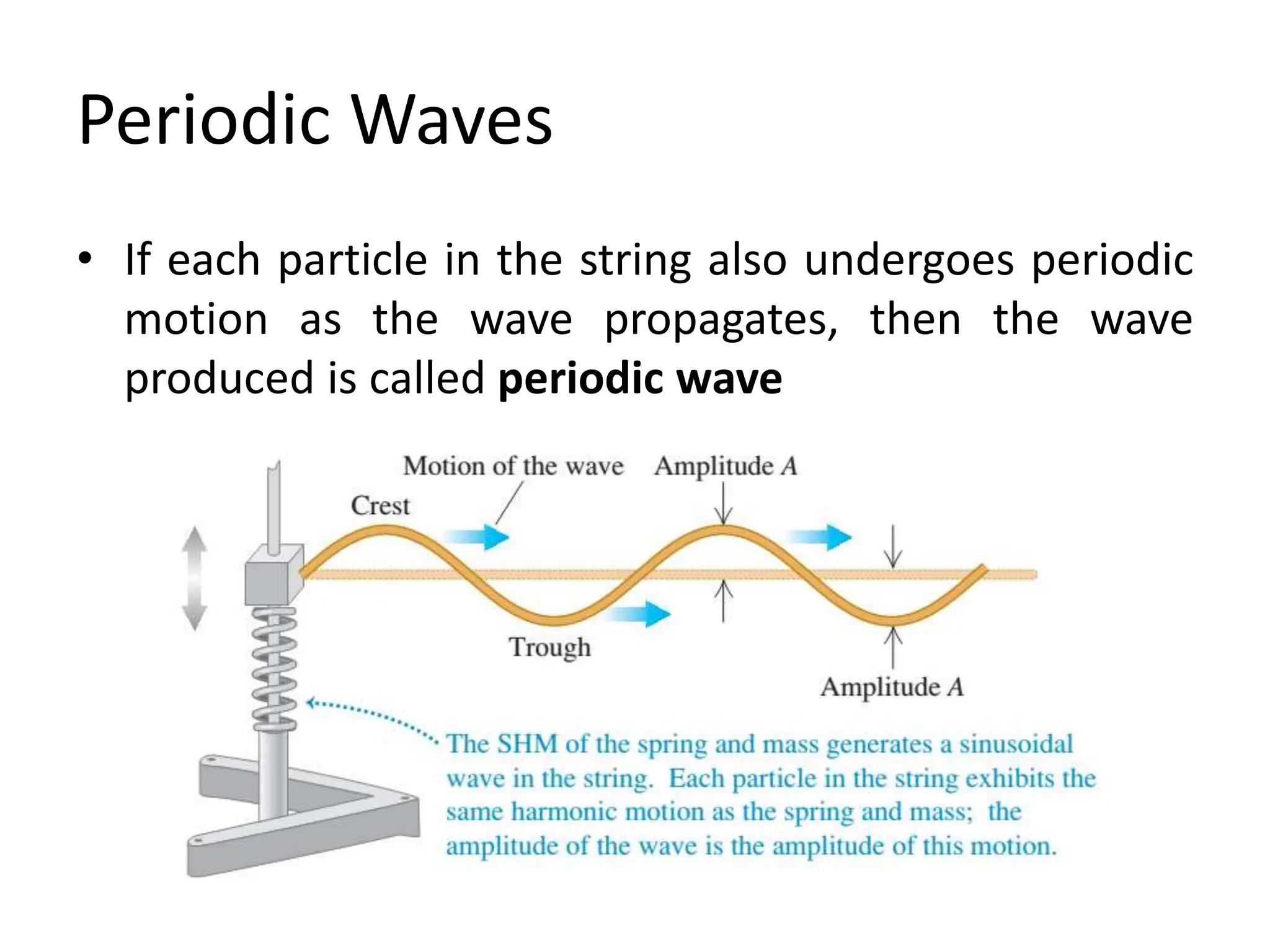

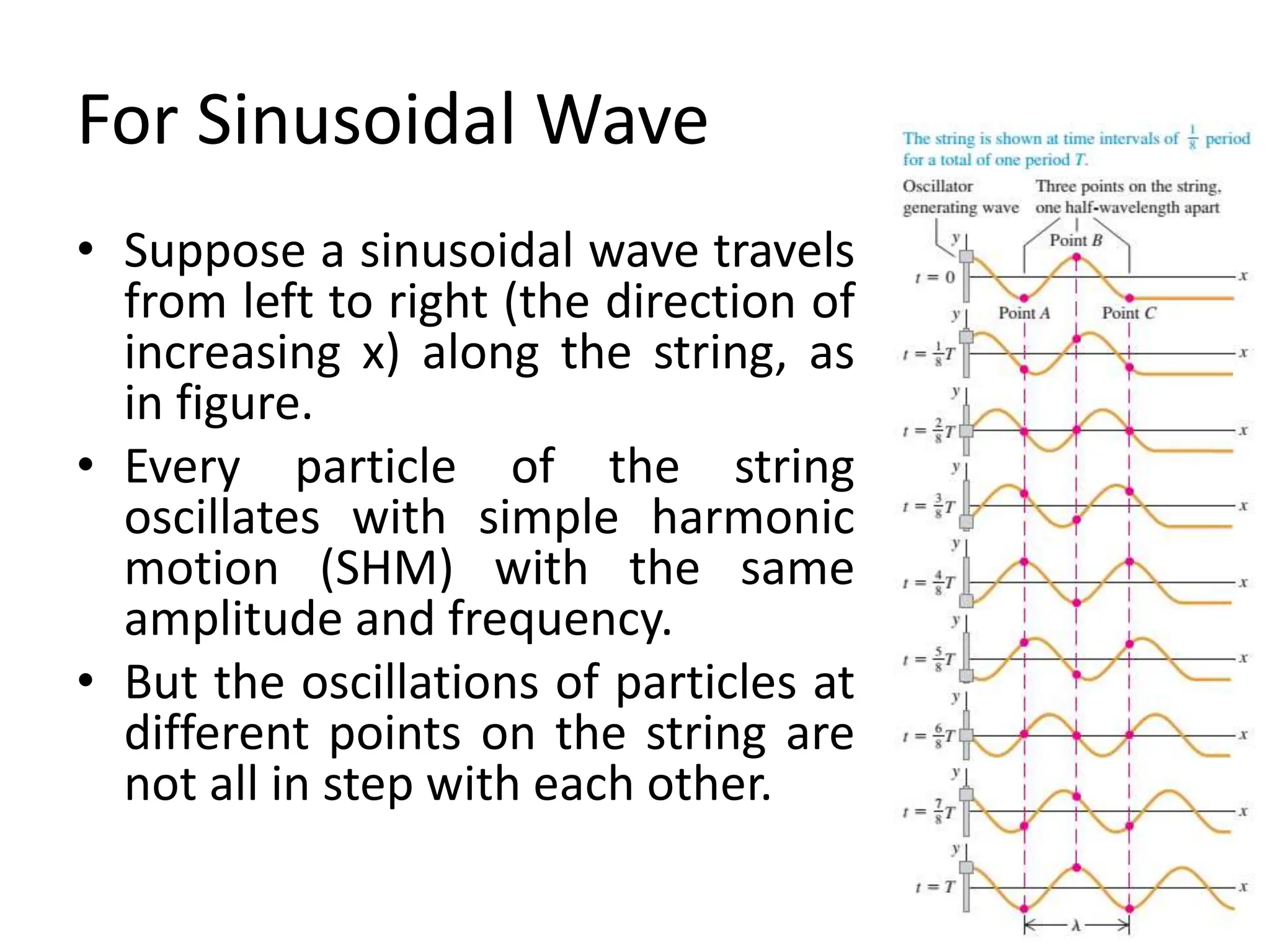

3. Periodic waves have particles undergoing simple harmonic motion, allowing their behavior to be described mathematically using wave functions involving variables like amplitude, wavelength, frequency, wave number, and phase.

4. The wave equation relates the second derivatives of a wave's displacement with respect to time and position, showing that disturbances can propagate as waves with a characteristic speed.

![Standing Waves on a String

• We can derive a wave function for the standing wave, adding

the wave functions for two waves with equal amplitude,

period, and wavelength traveling in opposite directions.

𝑦1 𝑥, 𝑡 = −𝐴 cos 𝑘𝑥 + 𝜔𝑡

𝑦2 𝑥, 𝑡 = +𝐴 cos 𝑘𝑥 − 𝜔𝑡

• The wave function for the standing wave is the sum of the

individual wave functions

𝑦 𝑥, 𝑡 = 𝑦1 𝑥, 𝑡 + 𝑦2 𝑥, 𝑡 = 𝐴 [−cos 𝑘𝑥 + 𝜔𝑡 + cos 𝑘𝑥 − 𝜔𝑡 ]

• By using the identities for the cosine

𝑦 𝑥, 𝑡 = 𝑦1 𝑥, 𝑡 + 𝑦2 𝑥, 𝑡 = 2𝐴 𝑠𝑖𝑛𝑘𝑥 sin 𝜔𝑡

𝑦 𝑥, 𝑡 = 𝐴𝑠𝑤 𝑠𝑖𝑛𝑘𝑥 sin 𝜔𝑡

Incident wave traveling to the left

Reflected wave traveling to the Right](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/mechanicalwaves-231027113844-03171545/75/Mechanical-waves-pptx-32-2048.jpg)