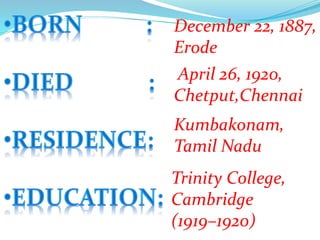

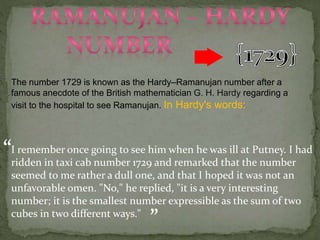

Srinivasa Ramanujan was an Indian mathematician born in 1887 in India. He was largely self-taught and made extraordinary contributions to mathematical analysis, number theory, infinite series, and continued fractions. Despite having no formal training, he rediscovered theorems and produced new original work. He collaborated with G.H. Hardy at Cambridge University in England, where he became a Fellow. Ramanujan died young at the age of 32 in 1920. He independently compiled nearly 3900 mathematical results, most of which have been proven correct. He introduced unconventional concepts that have inspired further research.

![Pancha-Siddhantika

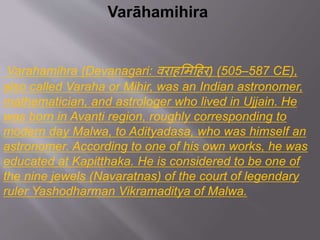

Varahamihir's main work is the book Pañcasiddhāntikā (or Pancha-Siddhantika,

"[Treatise] on the Five [Astronomical] Canons) dated ca. 575 CE gives us information

about older Indian texts which are now lost. The work is a treatise on mathematical

astronomy and it summaries five earlier astronomical treatises, namely the Surya

Siddhanta, Romaka Siddhanta, Paulisa Siddhanta, Vasishtha Siddhanta and

Paitamaha Siddhantas. It is a compendium of Vedanga Jyotisha as well as Hellenistic

astronomy (including Greek, Egyptian and Roman elements). He was the first one to

mention in his work Pancha Siddhantika that the ayanamsa, or the shifting of the

equinox is 50.32 seconds.

The 11th century Iranian scholar Alberuni also described the details of "The Five

Astronomical Canons":

"They [the Indians] have 5 Siddhāntas:

Sūrya-Siddhānta, i.e.. the Siddhānta of the Sun, composed by Lāṭadeva,

Vasishtha-siddhānta , so called from one of the stars of the Great Bear,

composed by Vishnucandra,

Pulisa-siddhānta, so called from Paulisa, the Greek, from the city of Saintra,

which is supposed to be Alexandria, composed by Pulisa.

Romaka-siddhānta, so called from the Rūm, i.e.. the subjects of the Roman

Empire, composed by Śrīsheṇa.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/mathematicians-181006151926/85/Mathematicians-36-320.jpg)

![Series

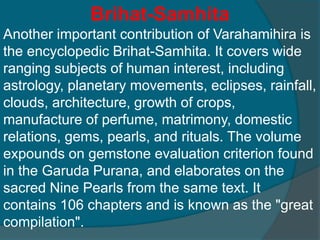

Brahmagupta then goes on to give the sum of the squares and cubes of the

first n integers.

12.20. The sum of the squares is that [sum] multiplied by twice the [number

of] step[s] increased by one [and] divided by three. The sum of the cubes is

the square of that [sum] Piles of these with identical balls [can also be

computed].

Here Brahmagupta found the result in terms of the sum of the first n integers,

rather than in terms of n as is the modern practice.

He gives the sum of the squares of the first n natural numbers as

n(n+1)(2n+1)/6 and the sum of the cubes of the first n natural numbers as

(n(n+1)/2)².

ALGEBRA

=

and](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/mathematicians-181006151926/85/Mathematicians-42-320.jpg)

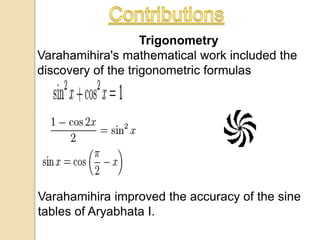

![Brahmagupta's most famous result in geometry is

his formula for cyclic quadrilaterals. Given the lengths

of the sides of any cyclic quadrilateral, Brahmagupta

gave an approximate and an exact formula for the

figure's area,

The approximate area is the product of the halves of

the sums of the sides and opposite sides of a triangle

and a quadrilateral. The accurate [area] is the square

root from the product of the halves of the sums of the

sides diminished by [each] side of the quadrilateral.

So given the lengths p, q, r and s of a cyclic

quadrilateral, the approximate area is

while, letting

the exact area is

Although Brahmagupta does not explicitly state that these quadrilaterals are cyclic, it is

apparent from his rules that this is the case. Heron's formula is a special case of this

formula and it can be derived by setting one of the sides equal to zero.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/mathematicians-181006151926/85/Mathematicians-43-320.jpg)