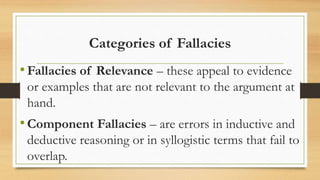

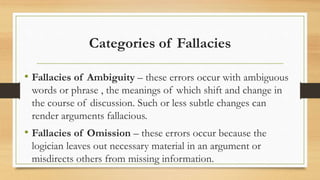

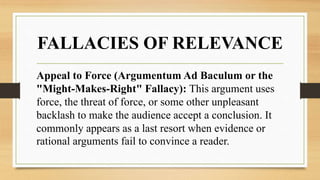

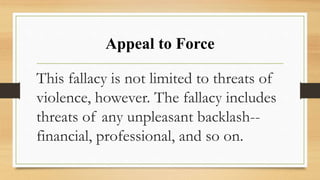

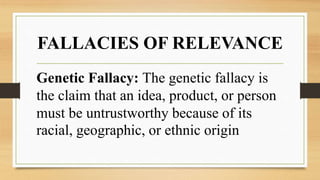

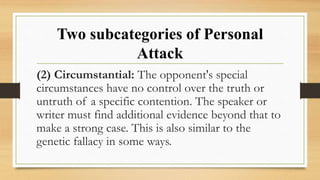

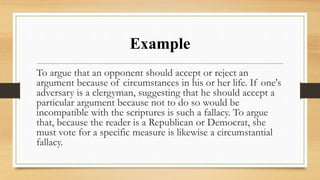

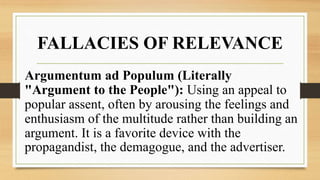

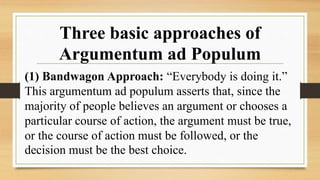

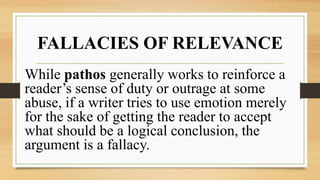

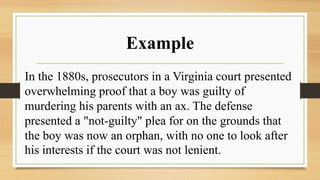

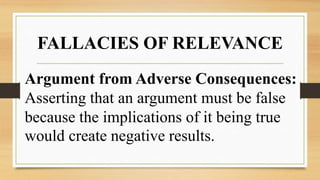

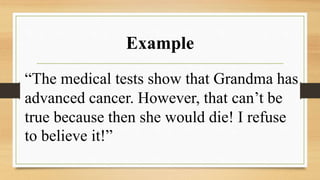

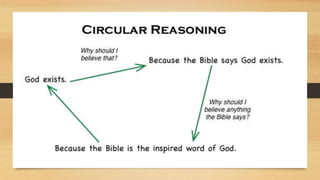

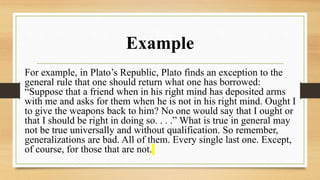

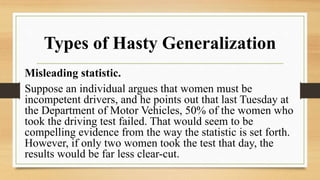

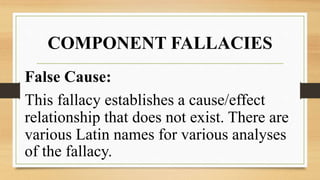

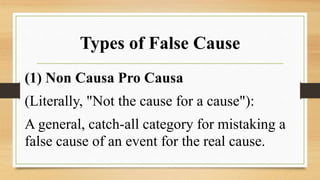

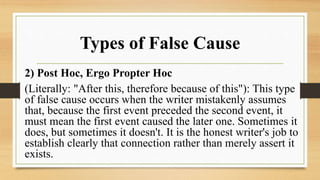

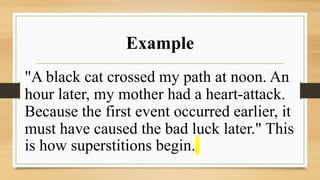

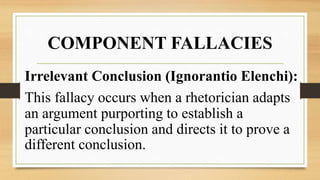

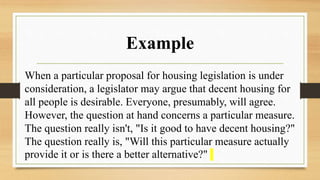

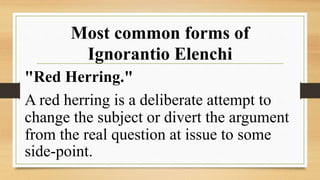

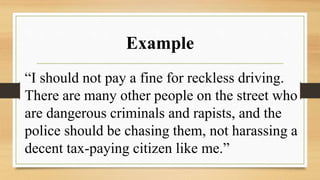

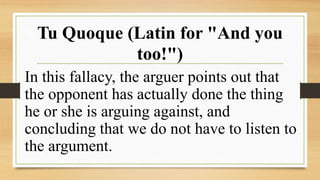

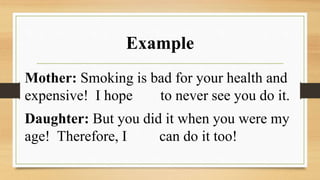

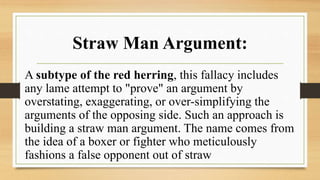

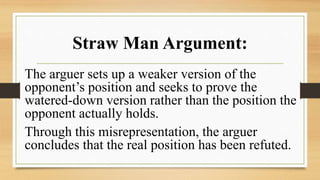

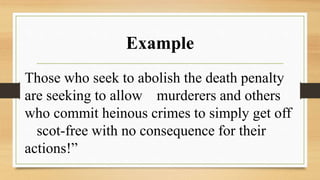

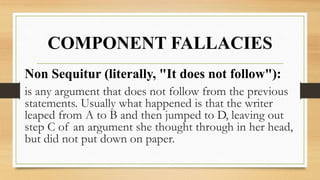

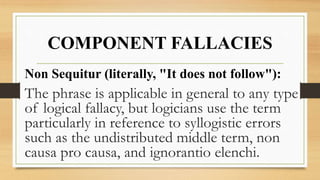

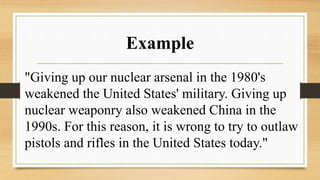

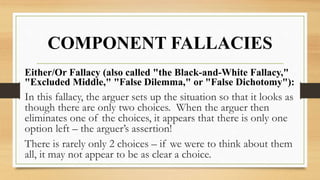

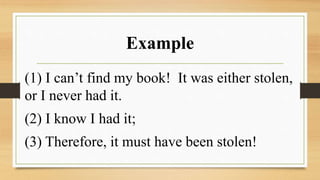

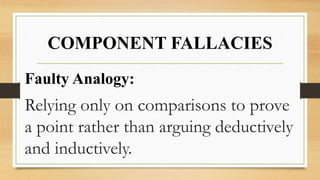

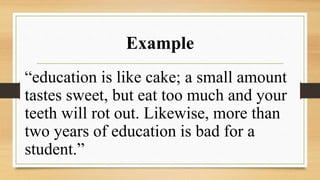

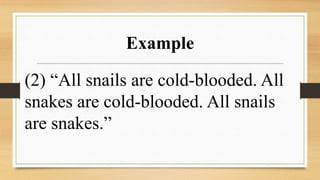

This document defines and provides examples of common logical fallacies. It discusses fallacies of relevance, including appeals to emotion, tradition, authority and popularity. It also covers fallacies of ambiguity, omission, and component fallacies involving faulty deductive or inductive reasoning. Specific fallacies explained include begging the question, slippery slope arguments, straw man, red herring, and non sequitur. The document aims to help readers identify flawed or dishonest arguments by learning to detect these common logical fallacies.