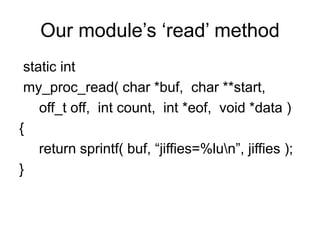

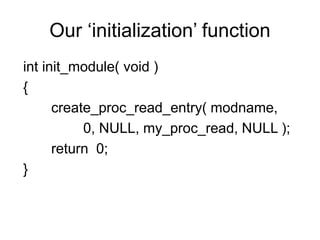

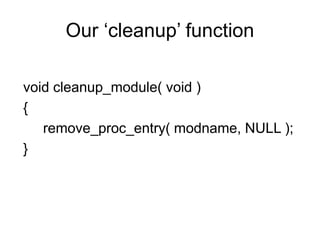

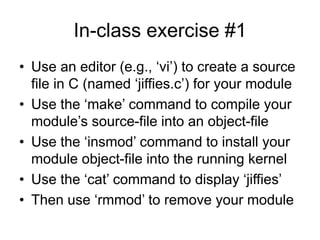

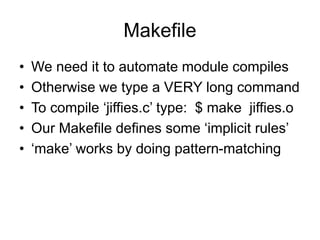

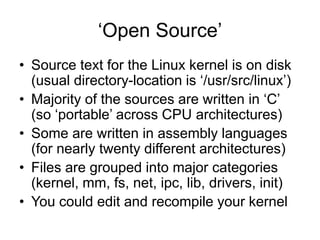

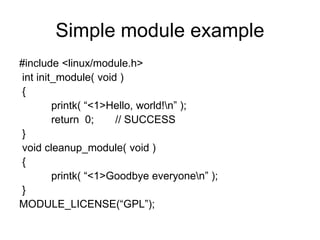

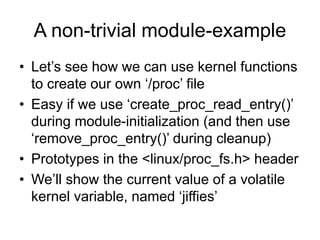

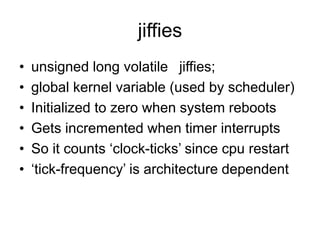

This document provides instructions for creating a kernel module that makes a pseudo-file in the Linux /proc filesystem. It explains how to write a module that uses the create_proc_read_entry() and remove_proc_entry() functions to register a proc file that displays the value of the jiffies kernel variable. Sample code is provided for a minimal module template and a non-trivial example module that creates a /proc/jiffies file to read jiffies.

![Writing the ‘jiffies.c’ module

• We need to declare a name for pseudo-file

static char modname[ ] = “jiffies”;

• We need to define a ‘proc_read’ function

(see code on the following slide)

• We need to ‘register’ our filename, along

with its ‘read’ method, in ‘init_module()’

• We need to ‘unregister’ our pseudo-file in

‘cleanup_module()’](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/lesson03-230608034741-21546b34/85/lesson03-ppt-15-320.jpg)