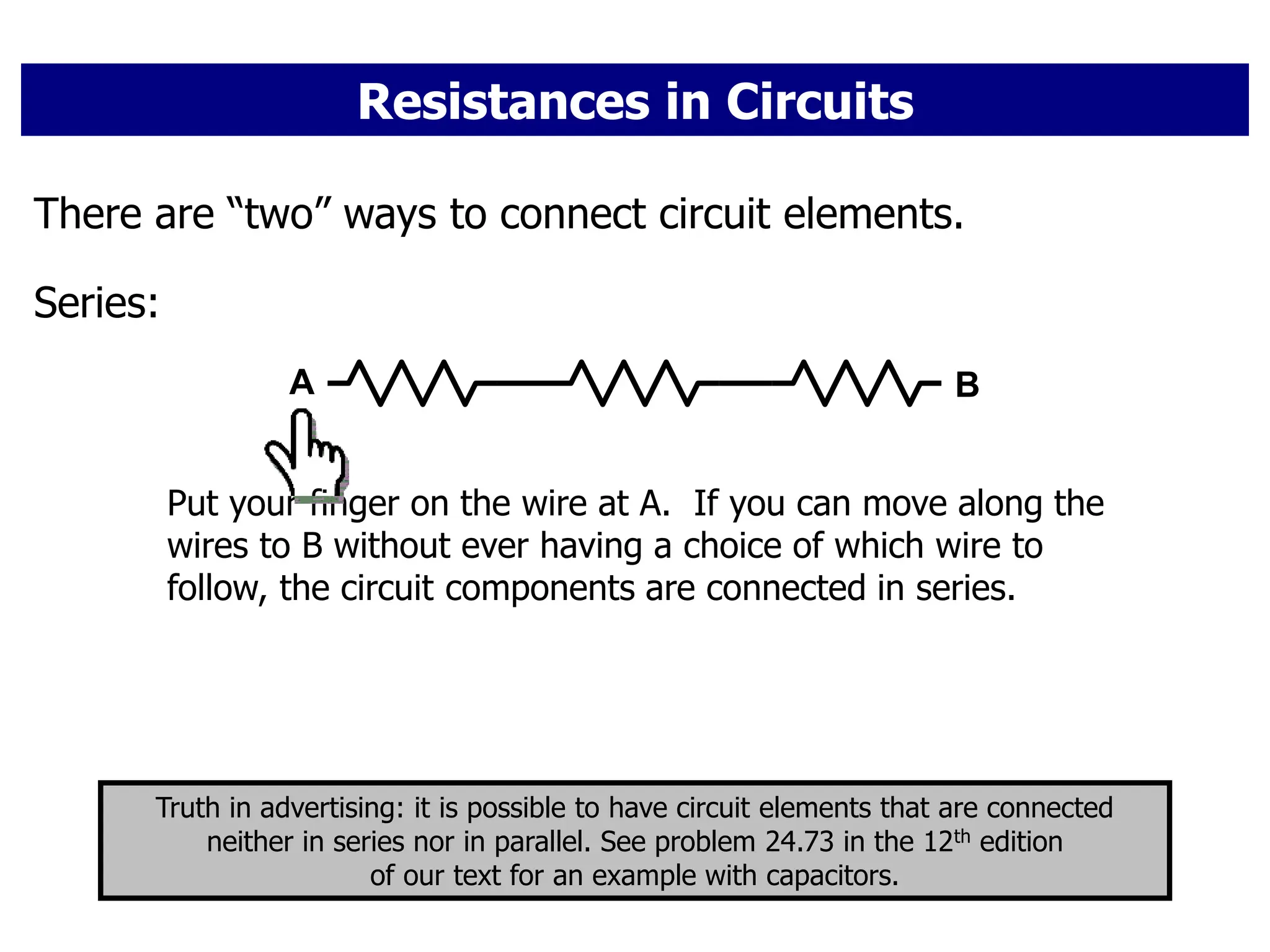

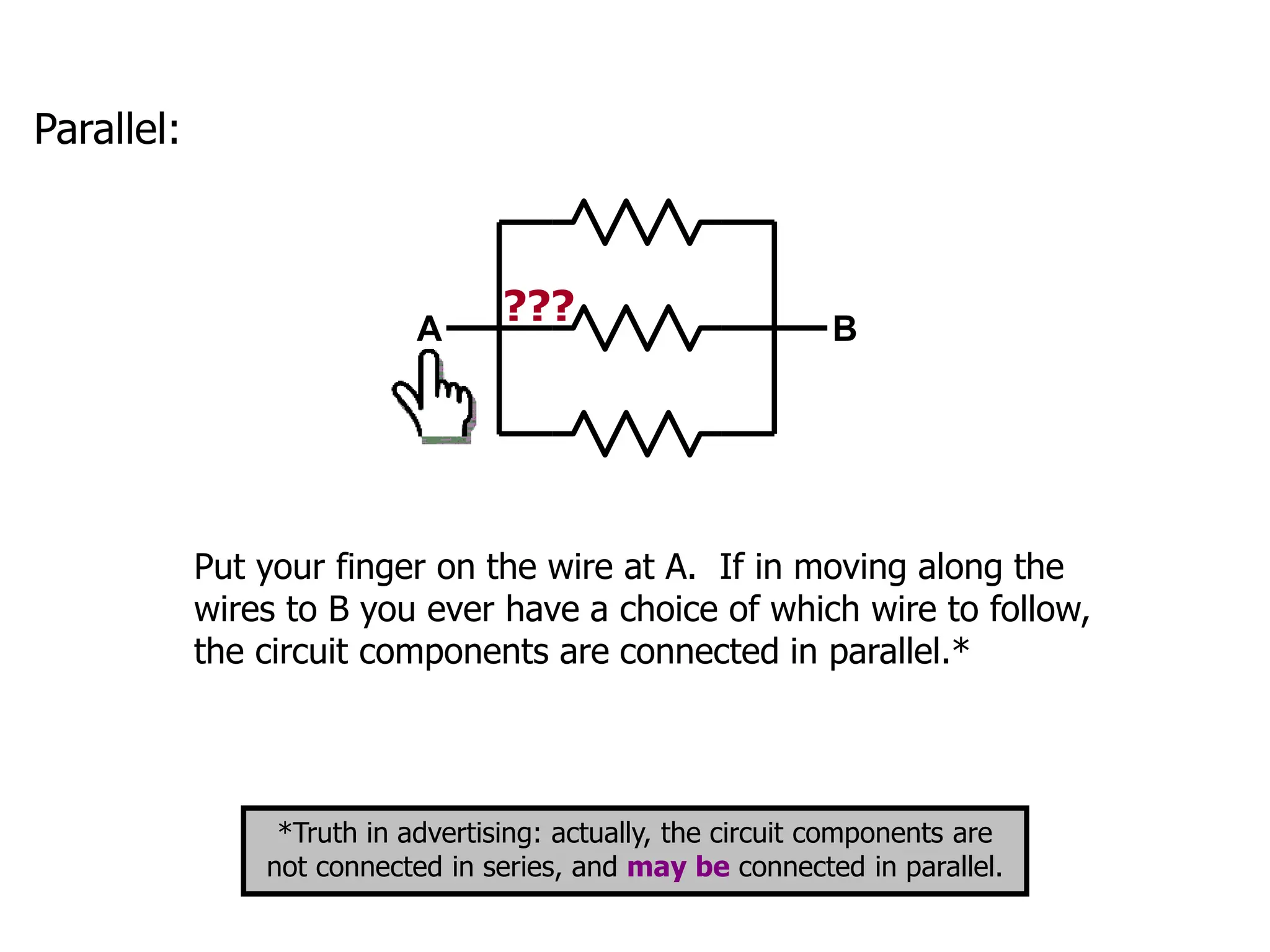

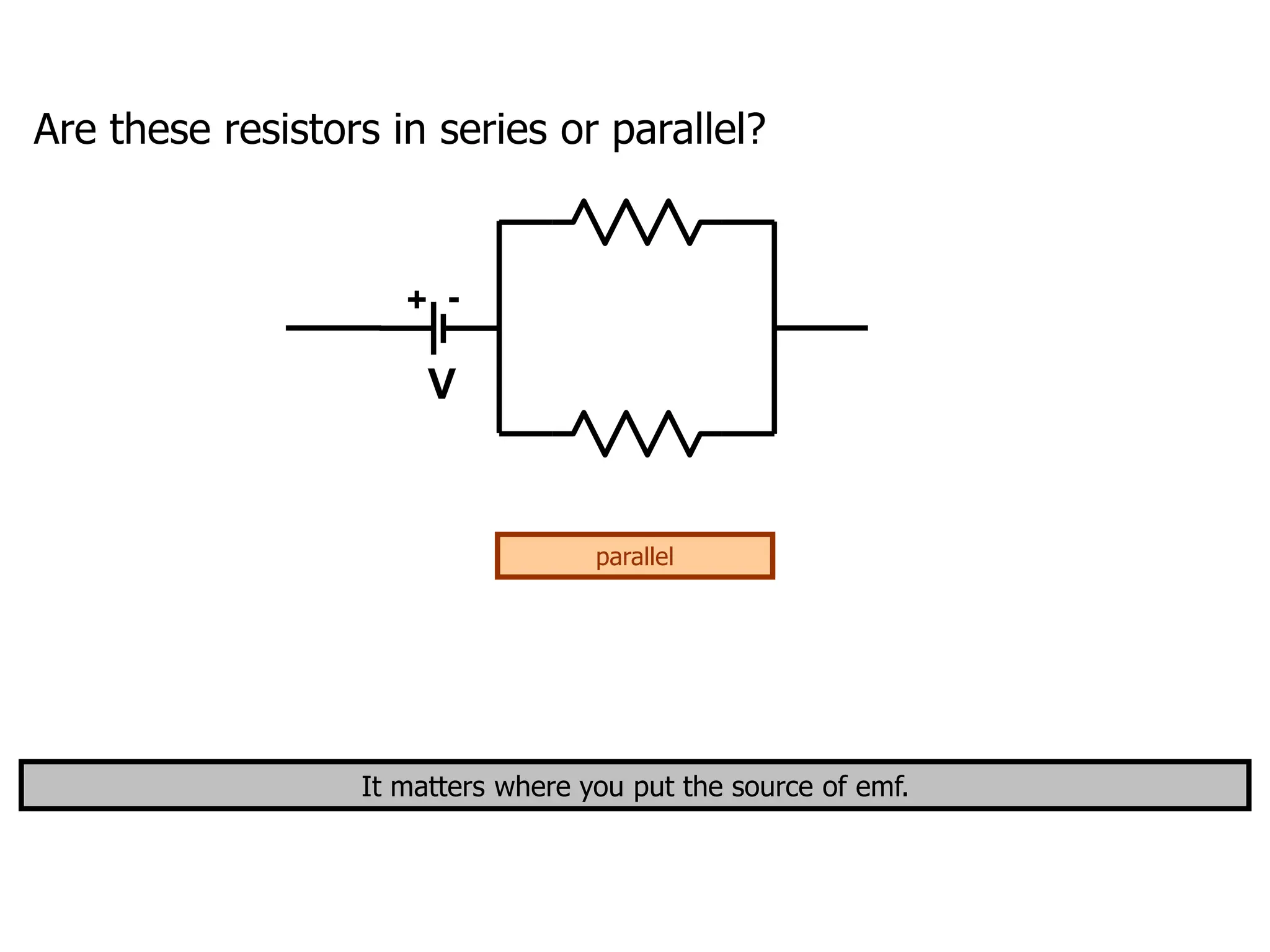

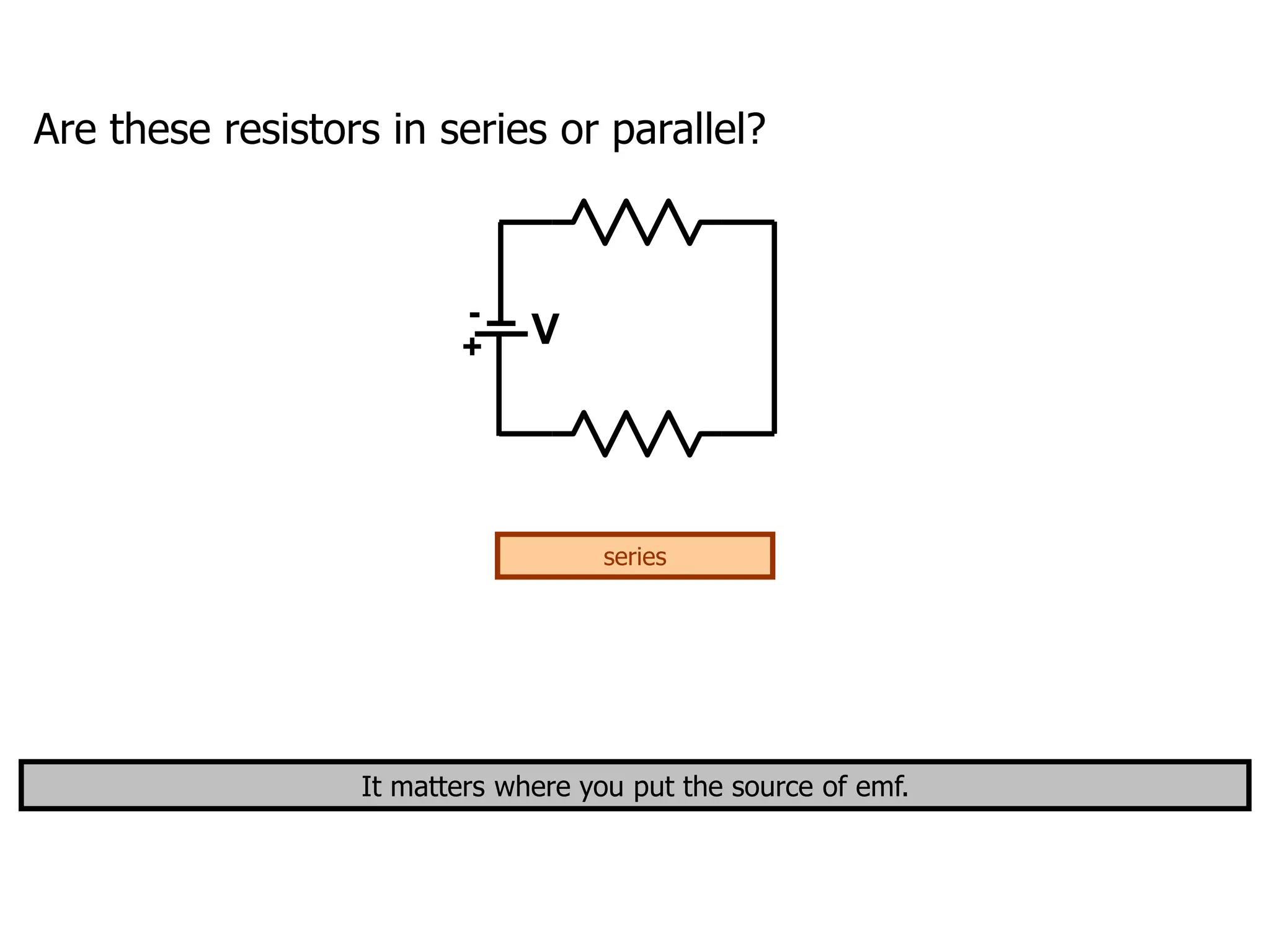

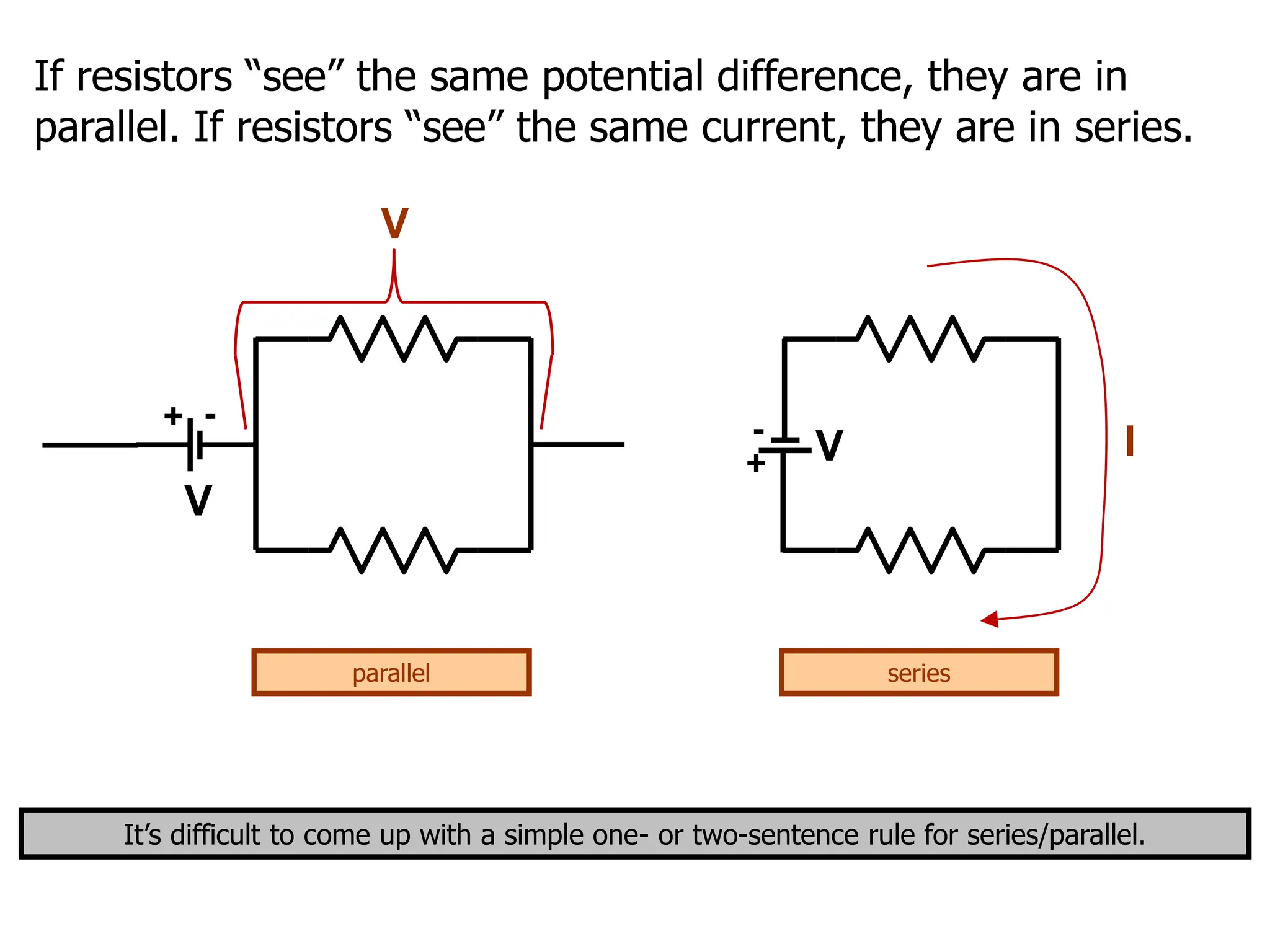

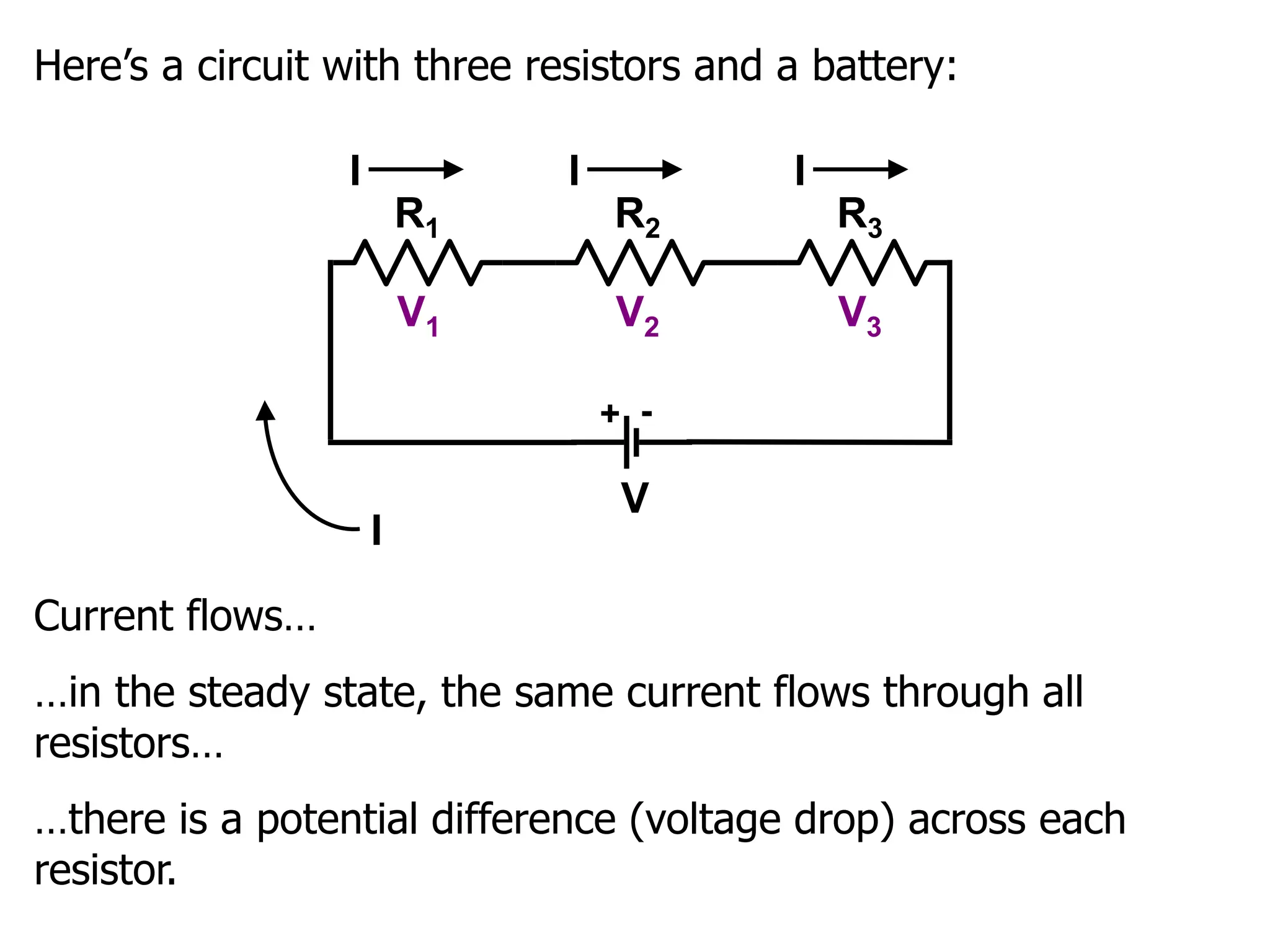

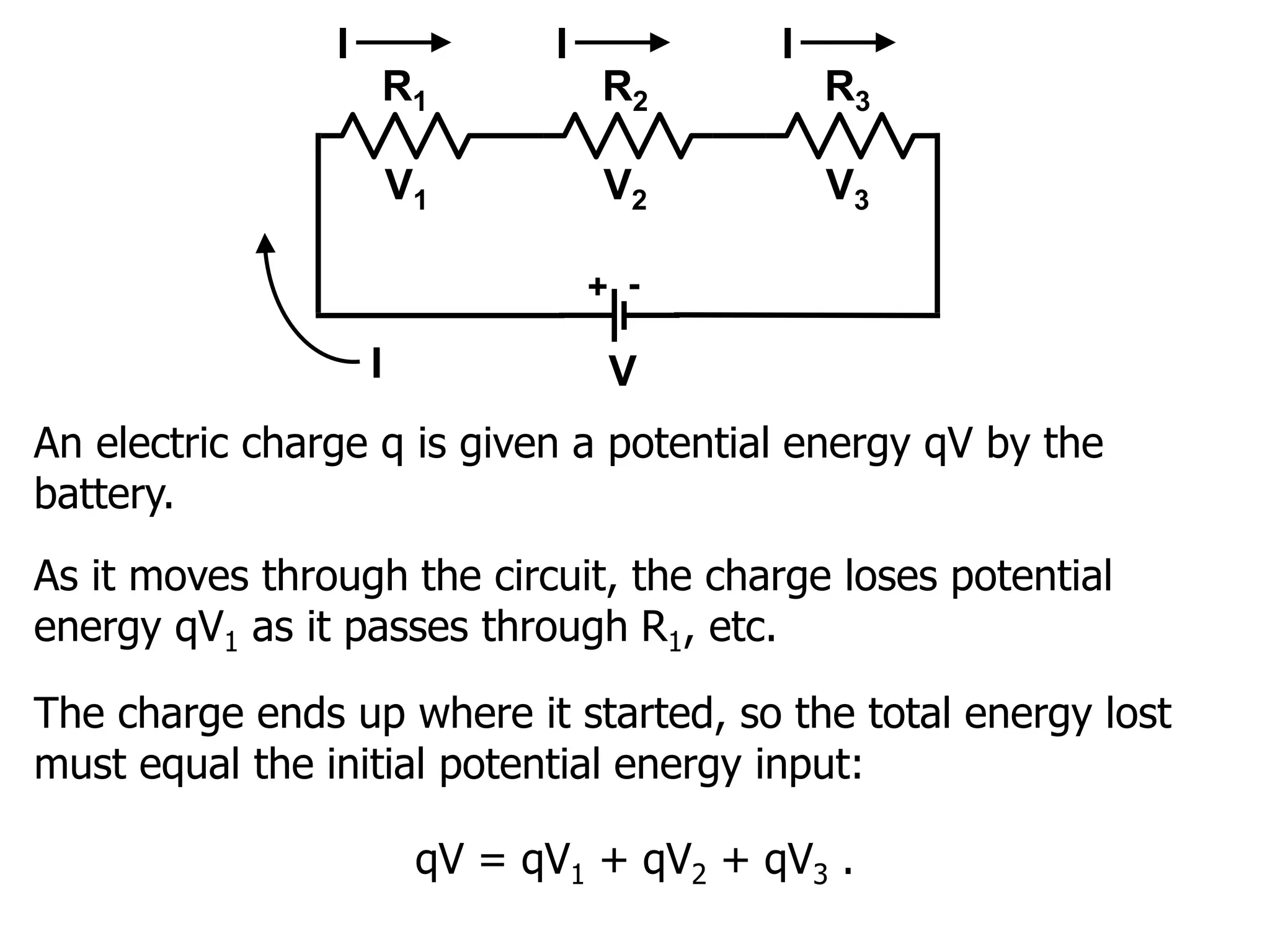

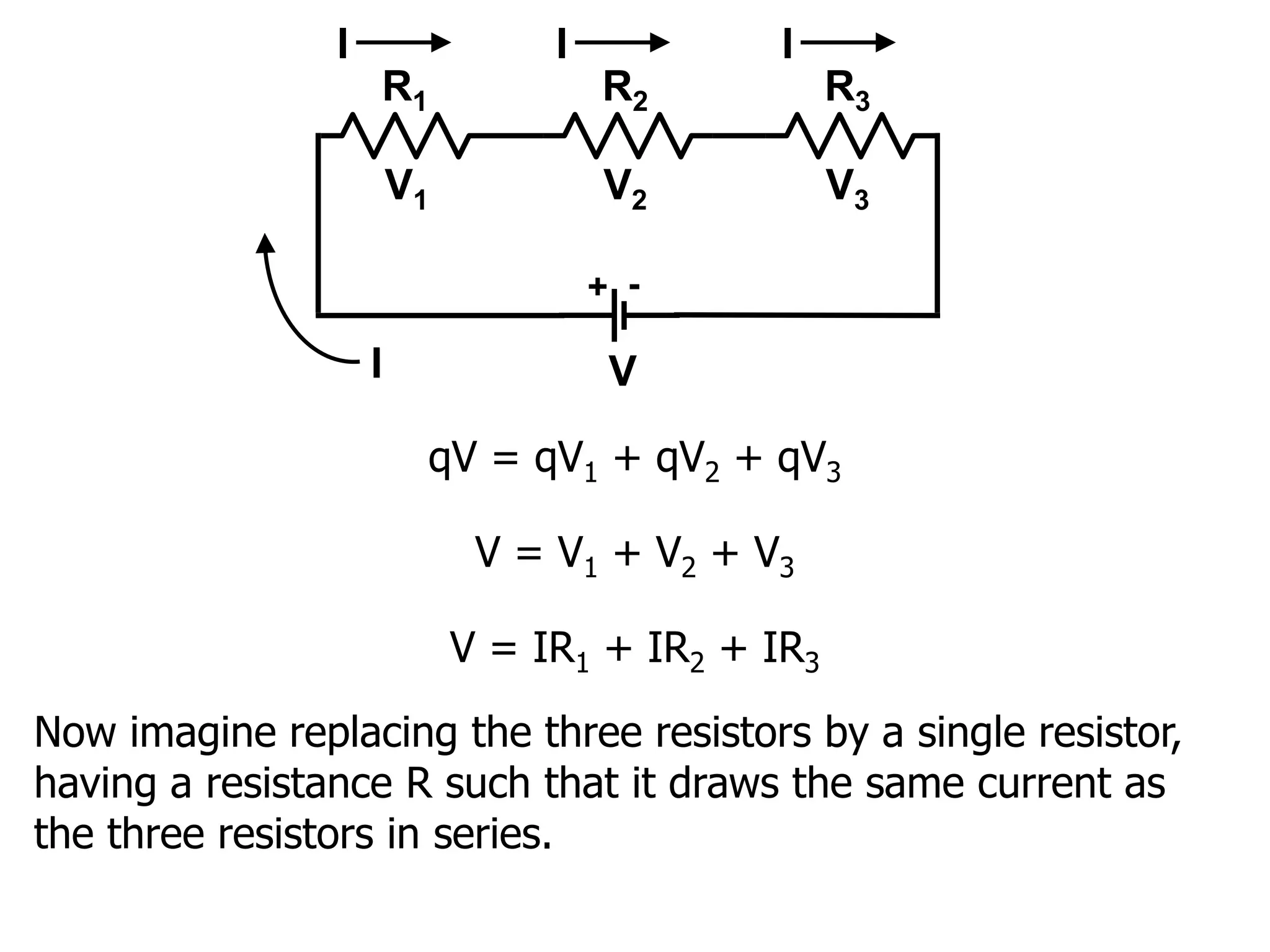

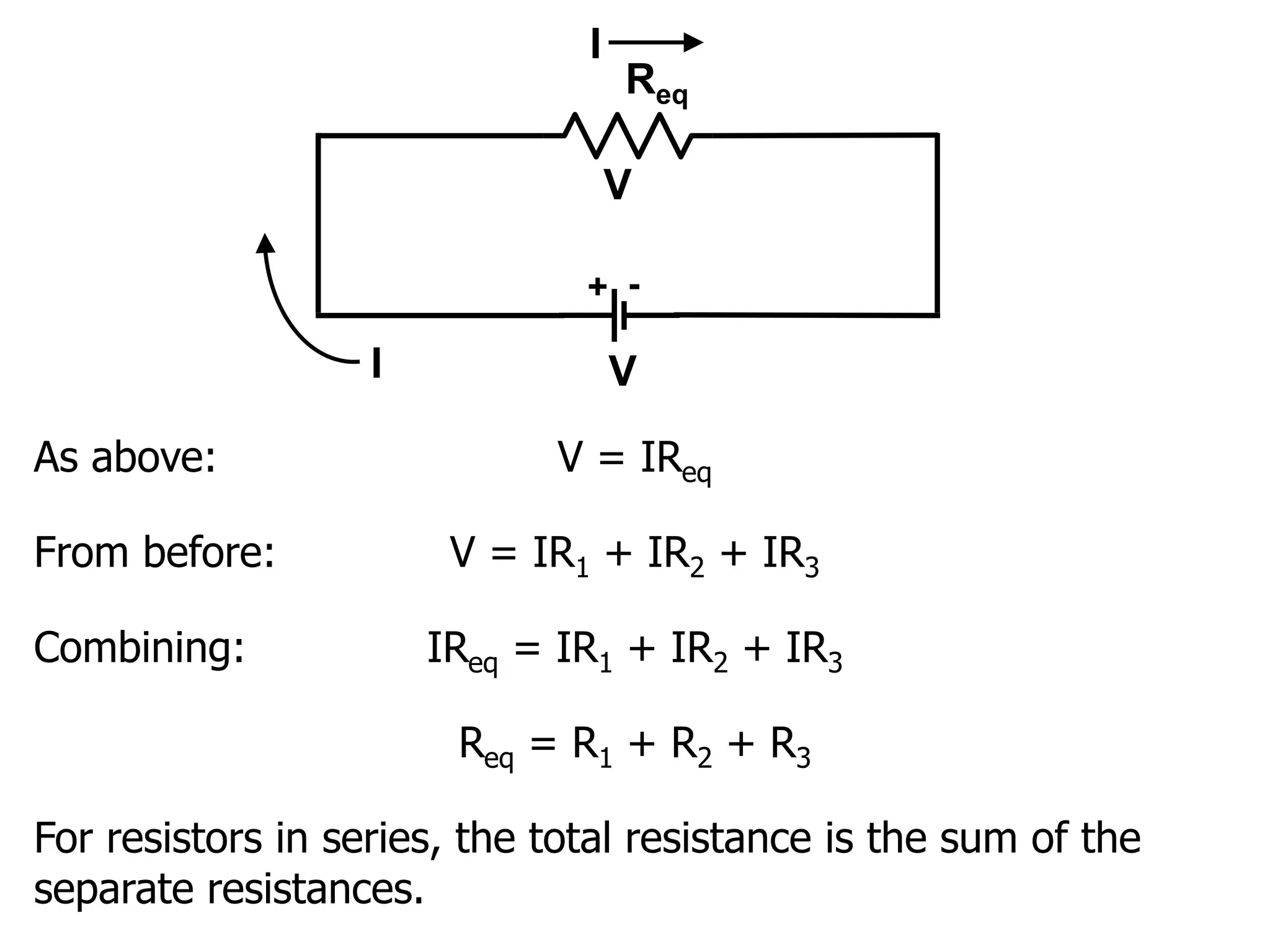

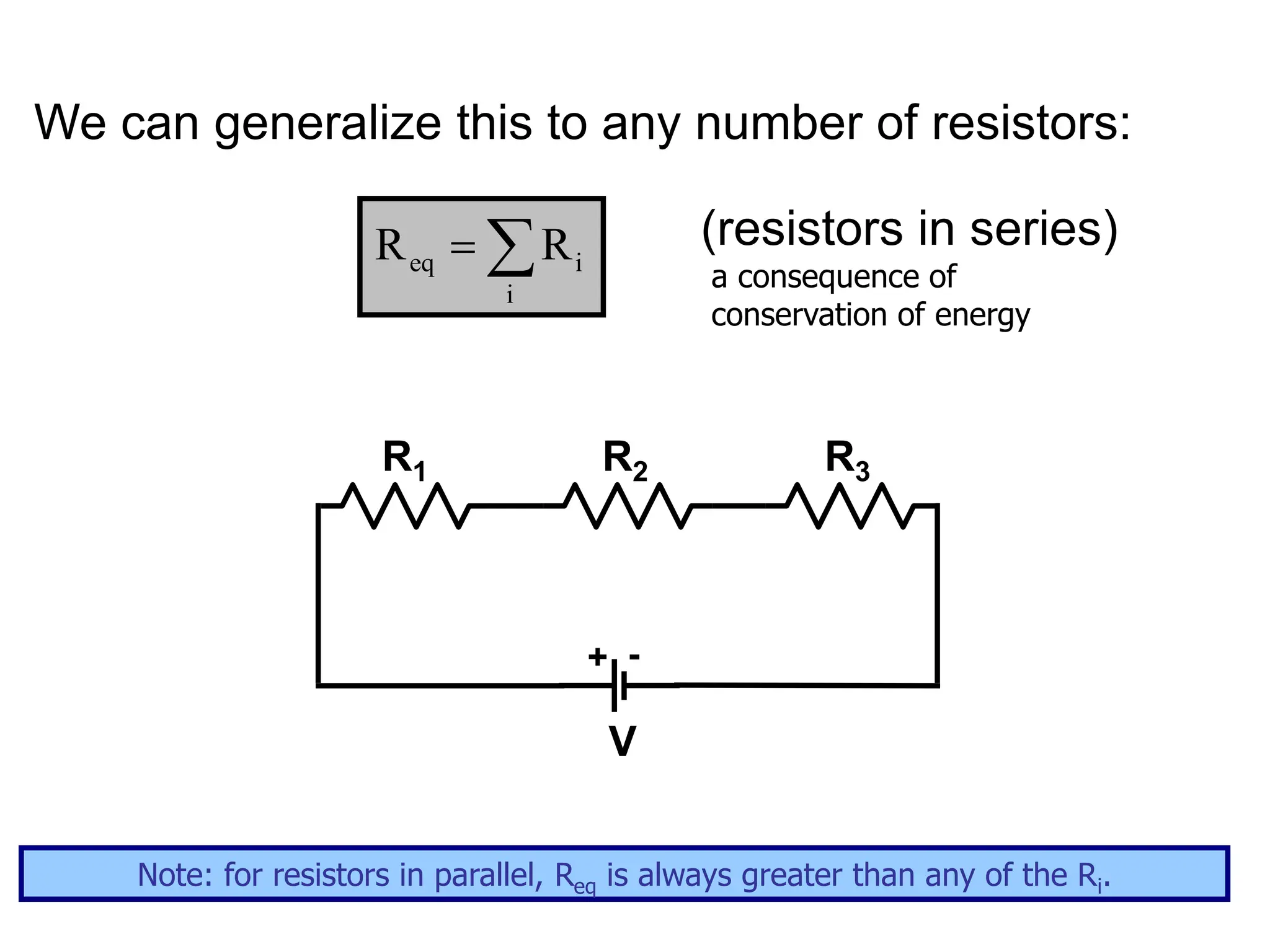

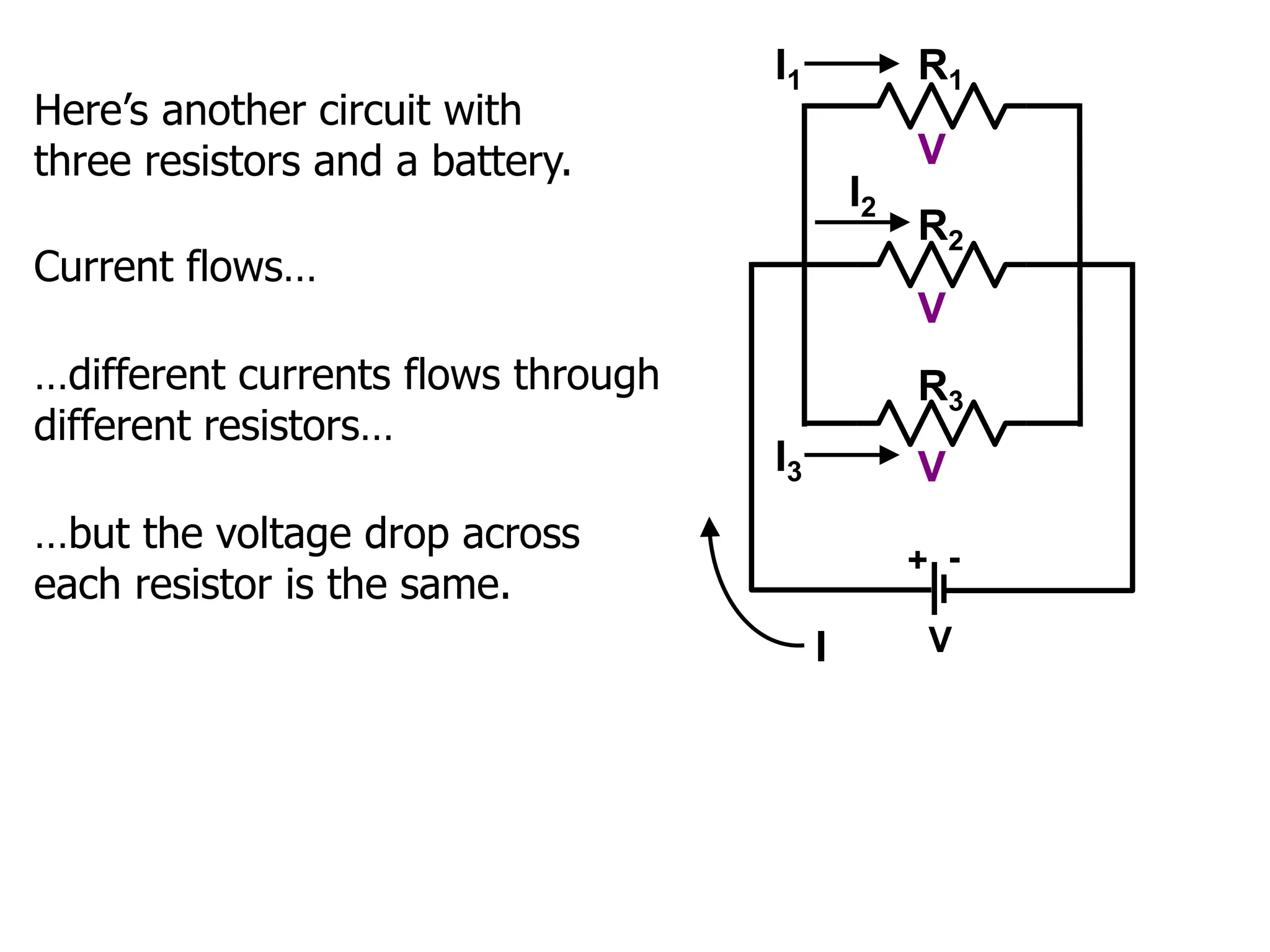

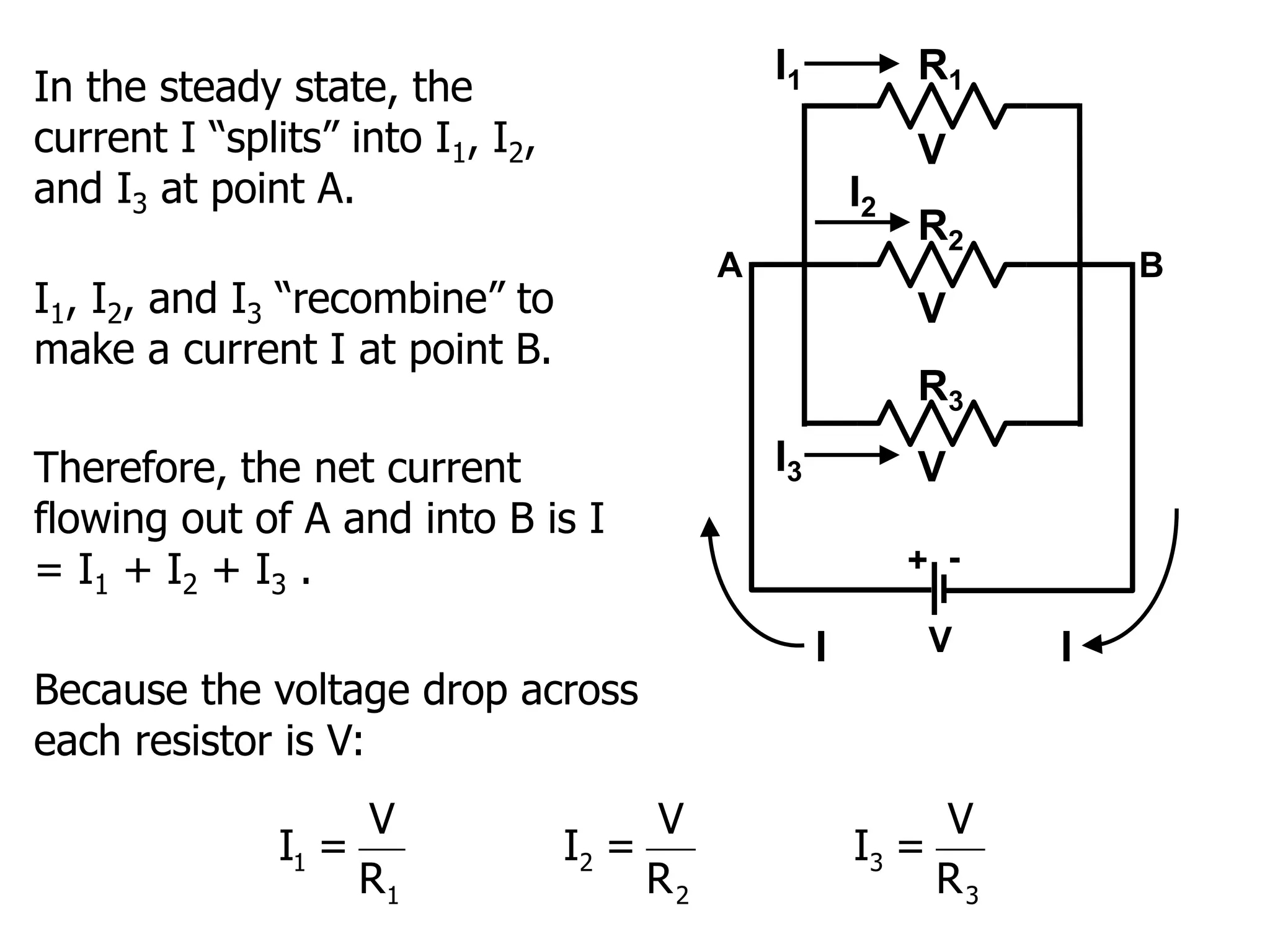

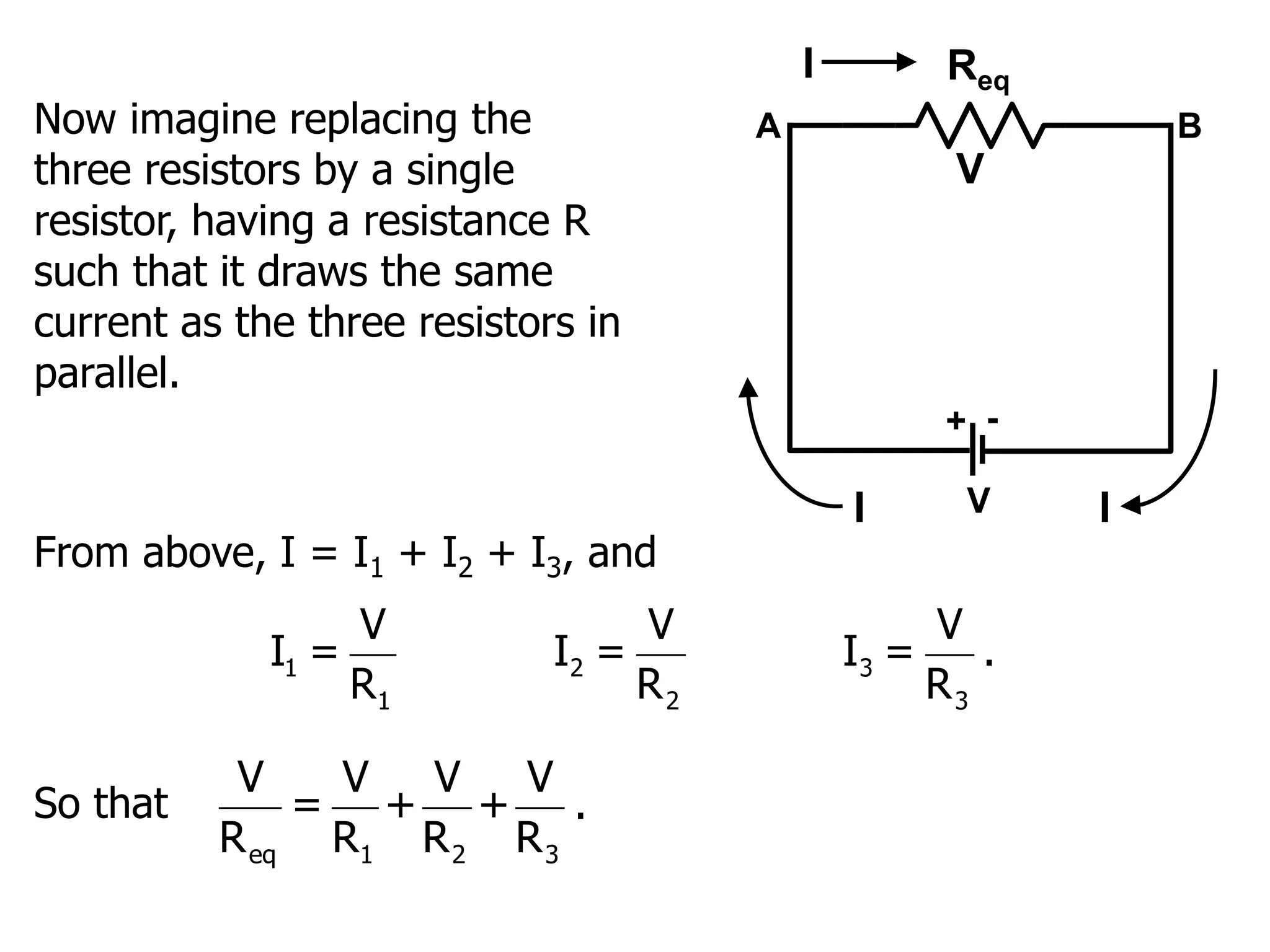

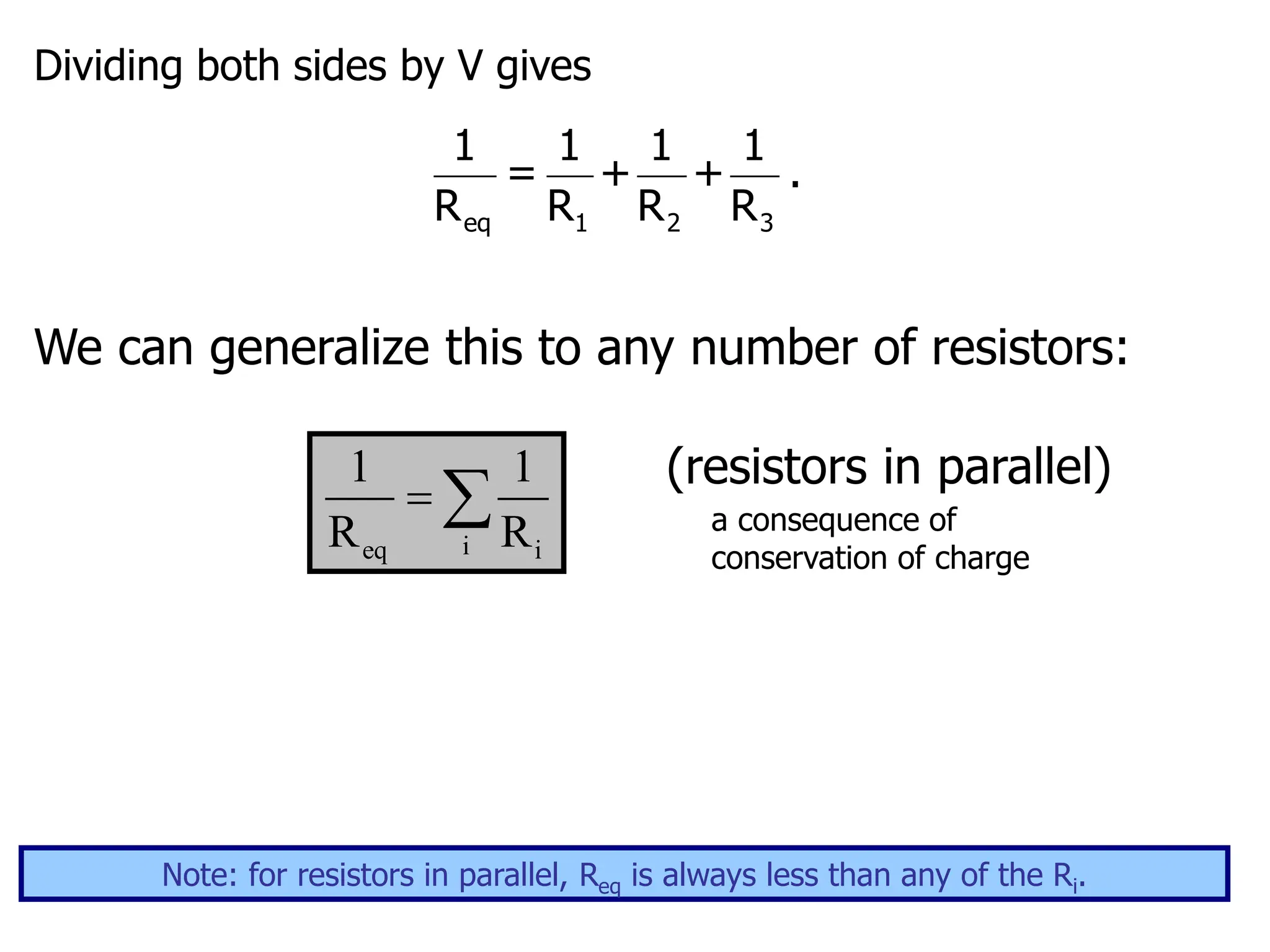

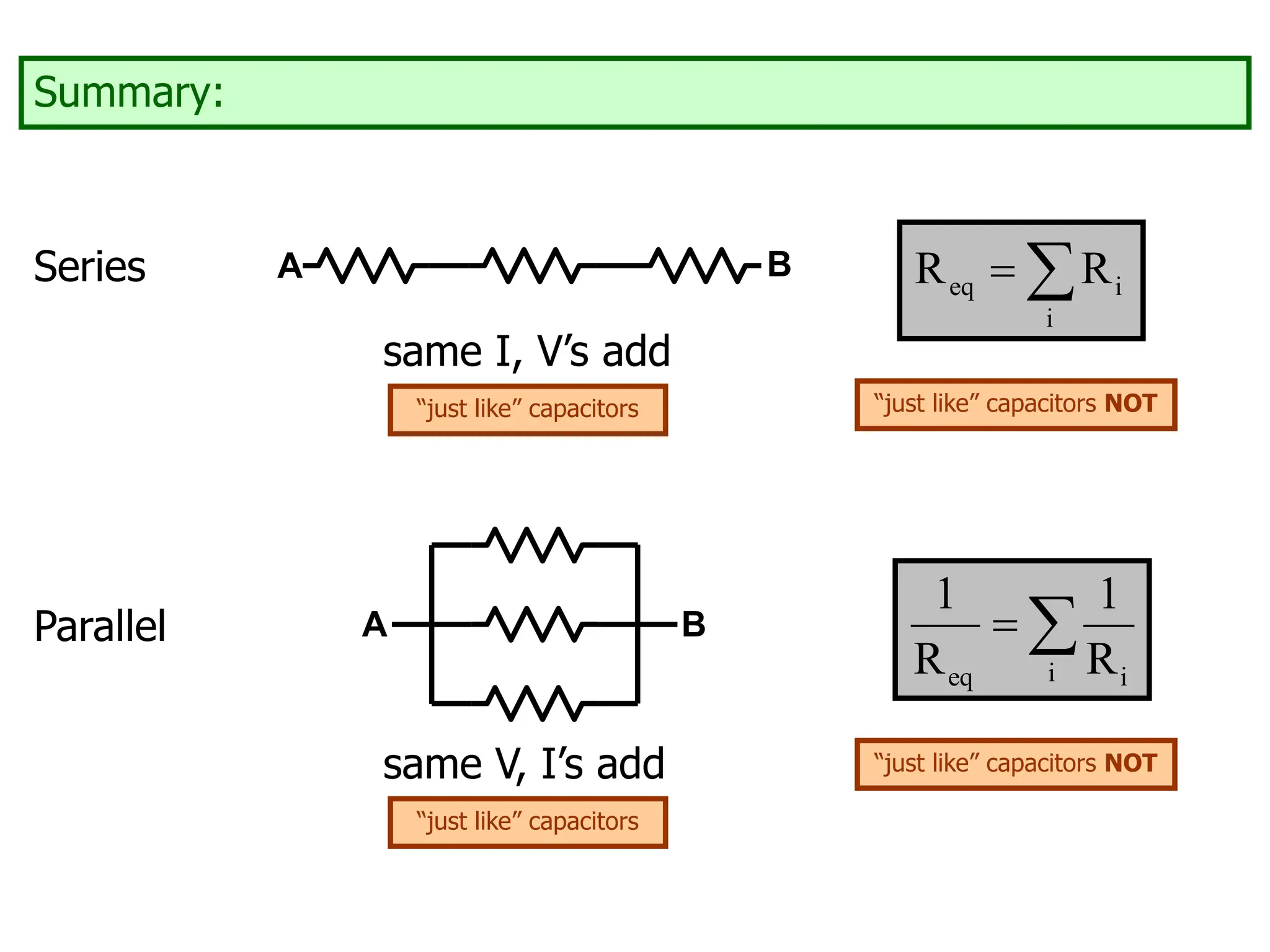

The document outlines the fundamental principles of resistors in series and parallel circuits, emphasizing the importance of calculating currents and voltages using Kirchhoff's rules. It describes the criteria for series and parallel connections, explains the conservation of energy and charge, and provides derivations for equivalent resistances in both configurations. Key takeaway: for series, total resistance is the sum of individual resistances, while for parallel, the reciprocal of the total resistance is the sum of the reciprocals of individual resistances.