This document discusses binary arithmetic and how numbers are represented in binary. It covers:

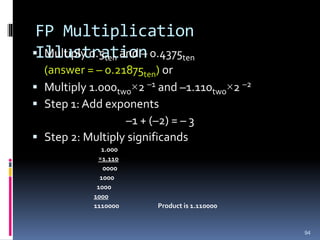

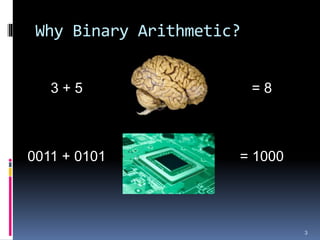

1. Why binary representation is used in digital circuits, as hardware can only deal with binary digits of 0 and 1.

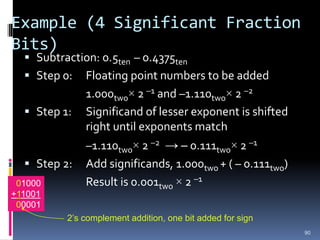

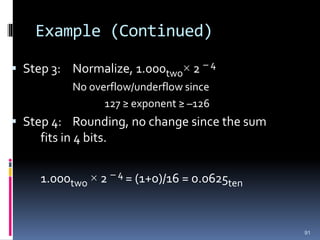

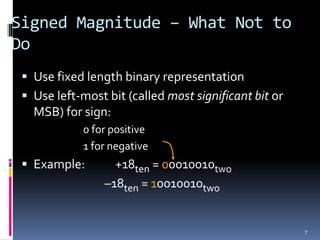

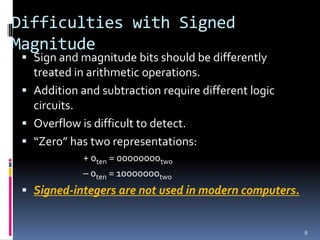

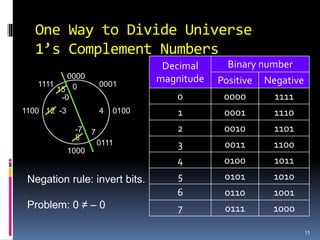

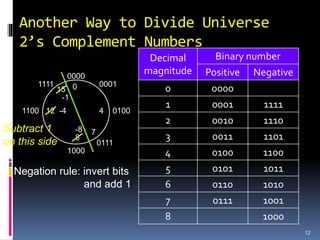

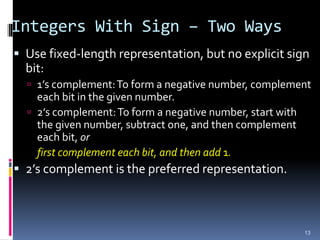

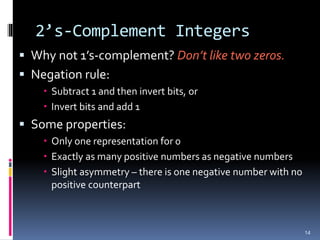

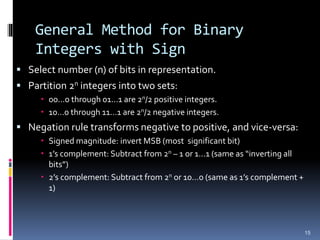

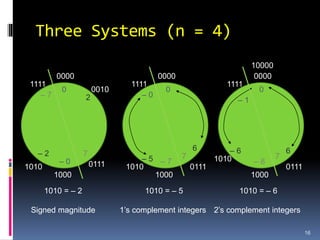

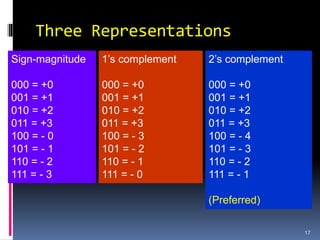

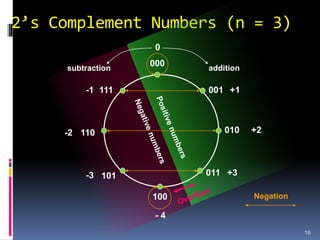

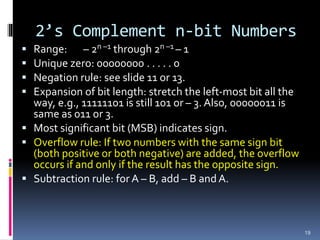

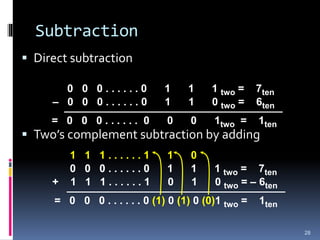

2. Different systems for representing signed integers in binary, including signed magnitude, 1's complement, and 2's complement representations. 2's complement is preferred as it has a unique zero value.

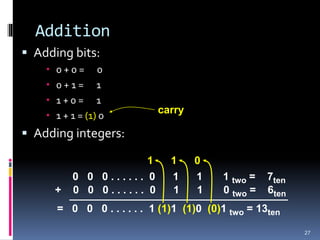

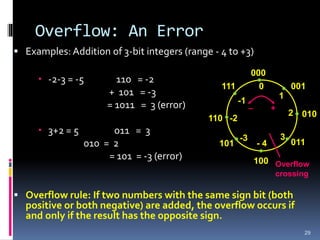

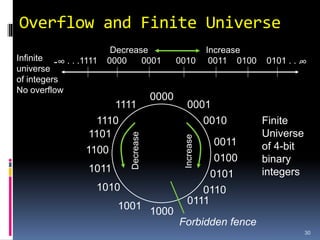

3. Arithmetic operations like addition, subtraction, and overflow handling in binary systems with a finite number of bits using the different signing methods.

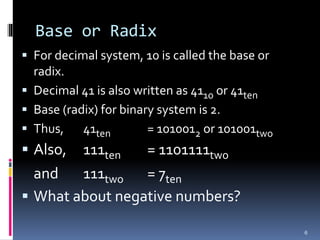

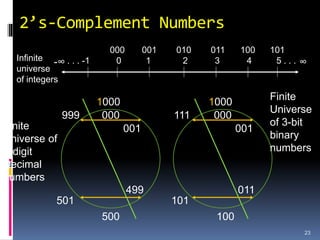

![Summary

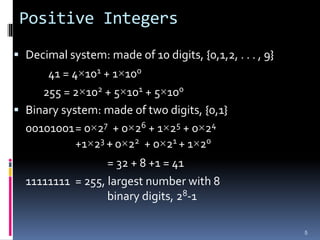

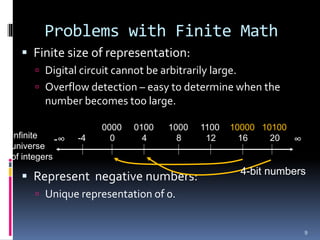

For a given number (n) of digits we have a finite

set of integers. For example, there are 103 = 1,000

decimal integers and 23 = 8 binary integers in 3-

digit representations.

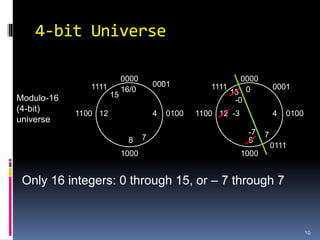

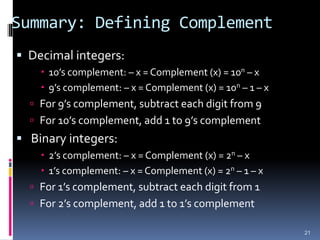

We divide the finite set of integers [0, rn – 1],

where radix r = 10 or 2, into two equal parts

representing positive and negative numbers.

Positive and negative numbers of equal

magnitudes are complements of each other: x +

complement (x) = 0.

20](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/lec2binaryarithmetic-230804044247-73d5aae9/85/lec2_BinaryArithmetic-ppt-20-320.jpg)

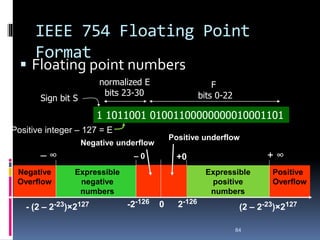

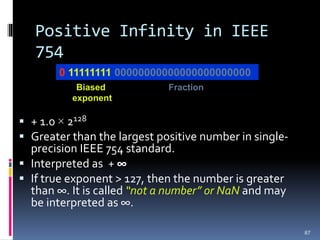

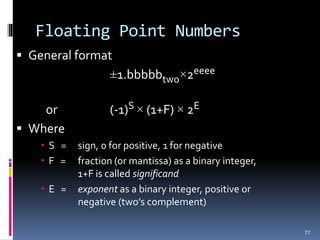

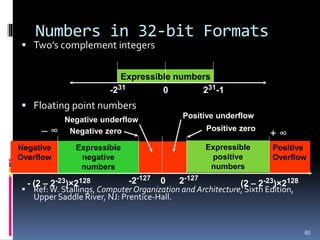

![IEEE 754 Floating Point

Standard

Biased exponent: true exponent range

[-126,127] is changed to [1, 254]:

Biased exponent is an 8-bit positive binary integer.

True exponent obtained by subtracting 127ten or

01111111two

First bit of significand is always 1:

± 1.bbbb . . . b × 2E

1 before the binary point is implicitly assumed.

Significand field represents 23 bit fraction after the binary

point.

Significand range is [1, 2), to be exact [1, 2 – 2-23]

81](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/lec2binaryarithmetic-230804044247-73d5aae9/85/lec2_BinaryArithmetic-ppt-81-320.jpg)