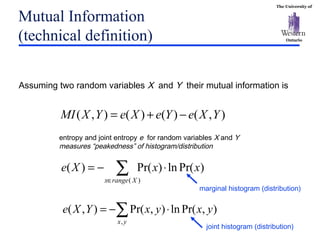

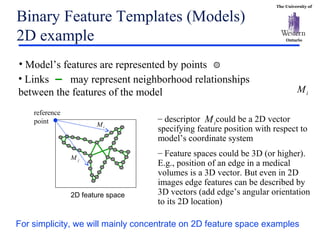

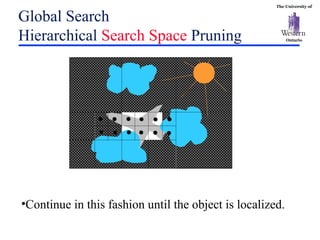

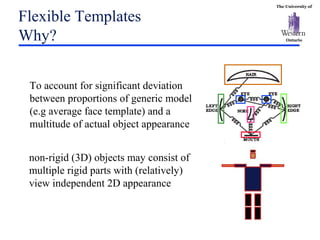

The document discusses template matching techniques for image analysis. It describes intensity-based template matching using metrics like sum of squared differences and normalized correlation to measure similarity between template and image intensities. Feature-based template matching is also covered, using distance transforms of binary edge images and metrics like chamfer distance and hausdorff distance. The document proposes using edge orientation information and spatial coherence of matches to make template matching more robust. It suggests hierarchical search techniques to efficiently prune the search space for the optimal template position.