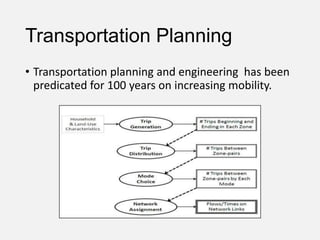

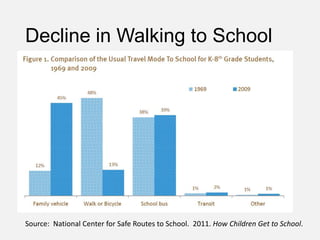

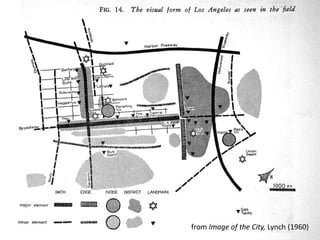

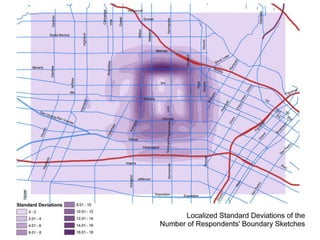

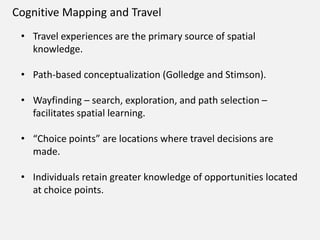

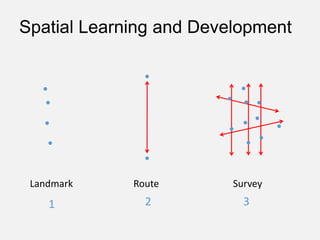

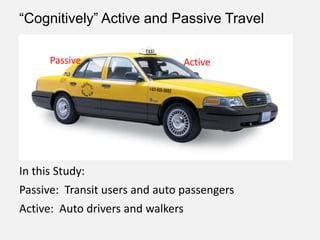

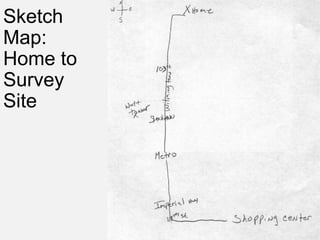

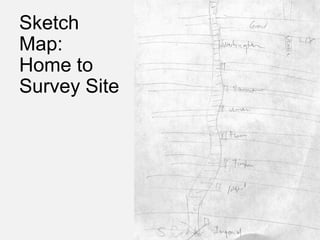

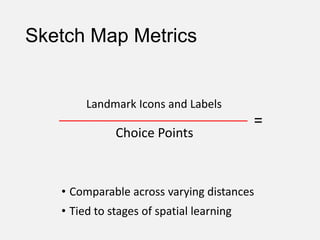

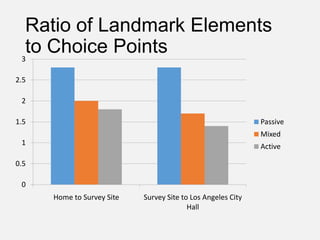

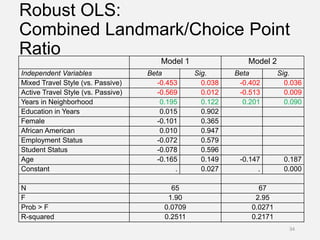

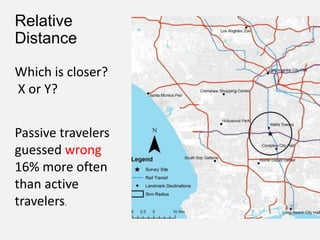

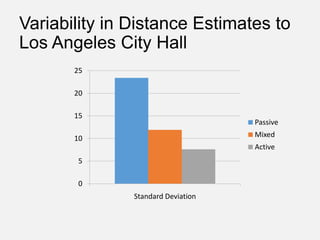

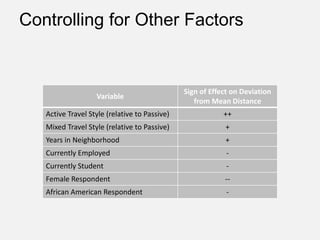

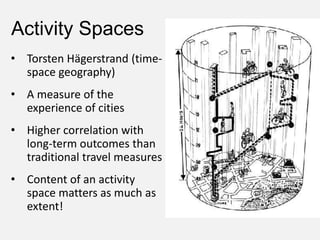

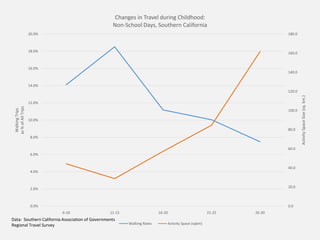

This document summarizes research on how early travel experiences shape people's cognitive maps and spatial knowledge of cities. It finds that active travel like walking and biking leads to better spatial learning than passive travel. Adolescence is a critical time for gaining urban knowledge. The decline in walking to school may negatively impact spatial development. Sketch maps revealed that active travelers included more landmarks and choice points than passive travelers. Promoting independent mobility in youth through urban design could foster more sustainable travel behaviors and spatial learning. Future research should further examine links between travel, learning, and development across different built environments.