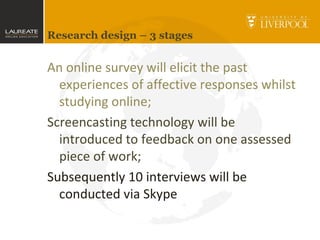

The study focuses on the affective responses of online students to technology, particularly the impact of screencasting on feedback delivery. It aims to understand how emotions influence learning experiences and the effectiveness of technology in fostering positive feelings. The research design includes an online survey, the use of screencasting for feedback, and interviews to analyze students' affective experiences.