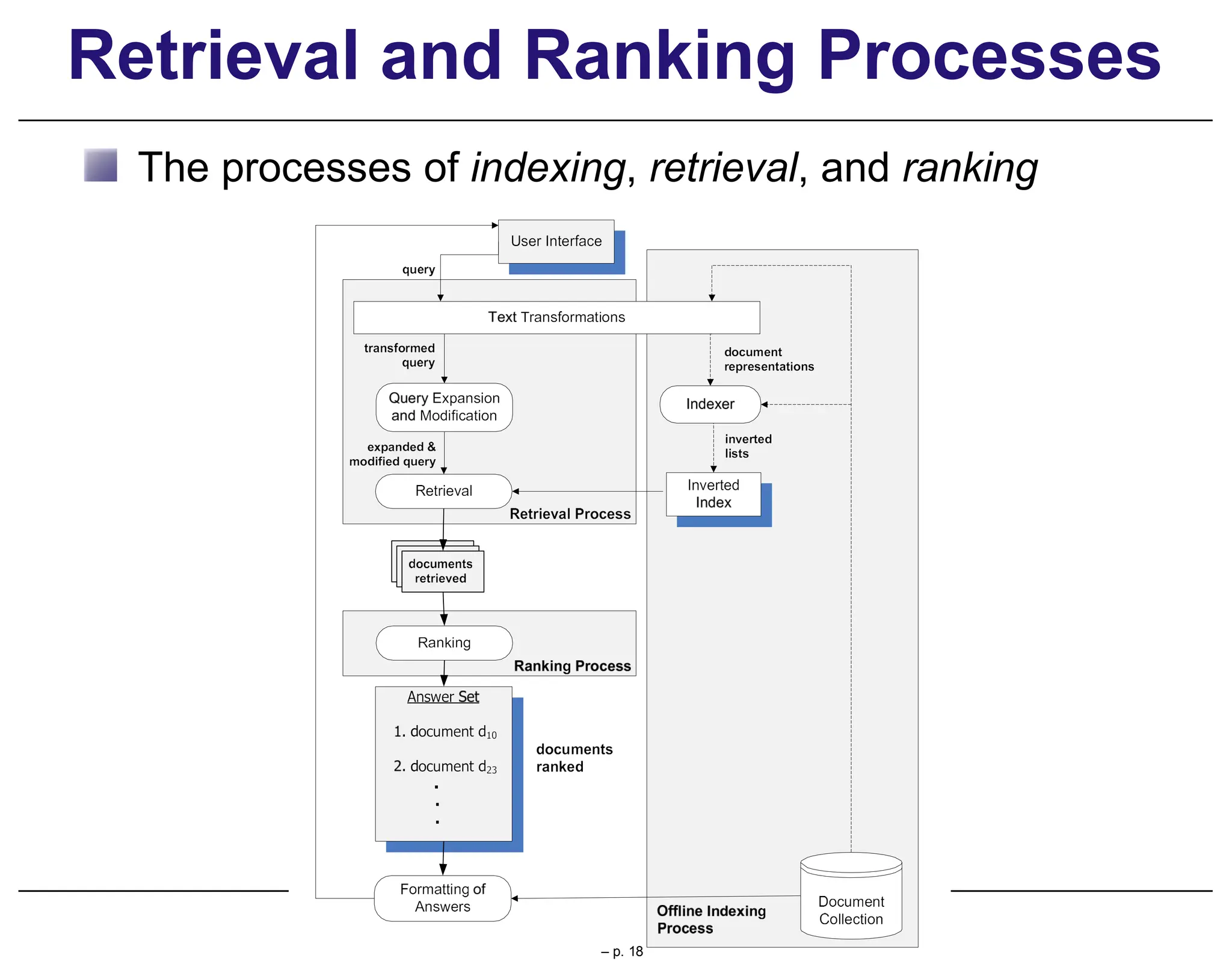

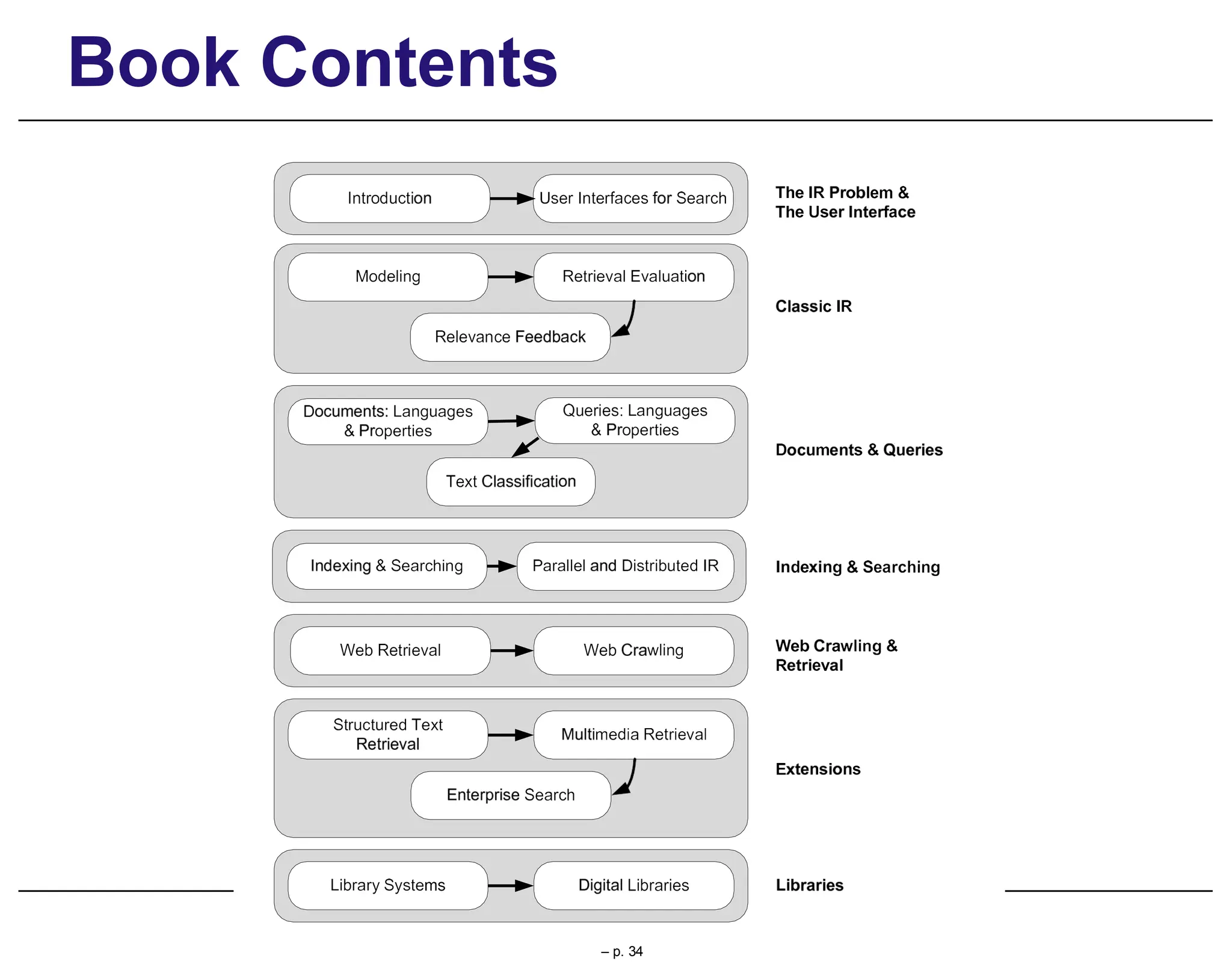

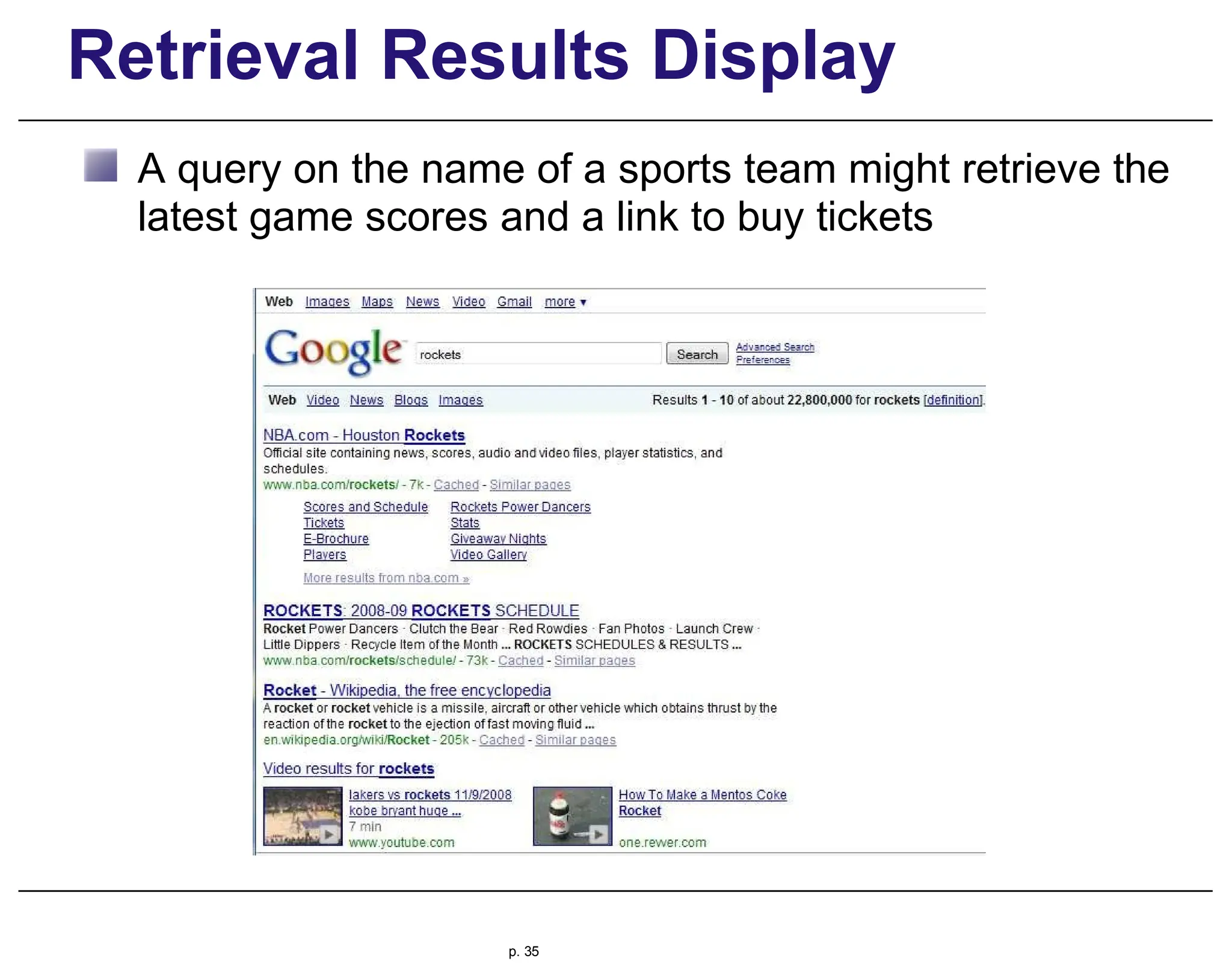

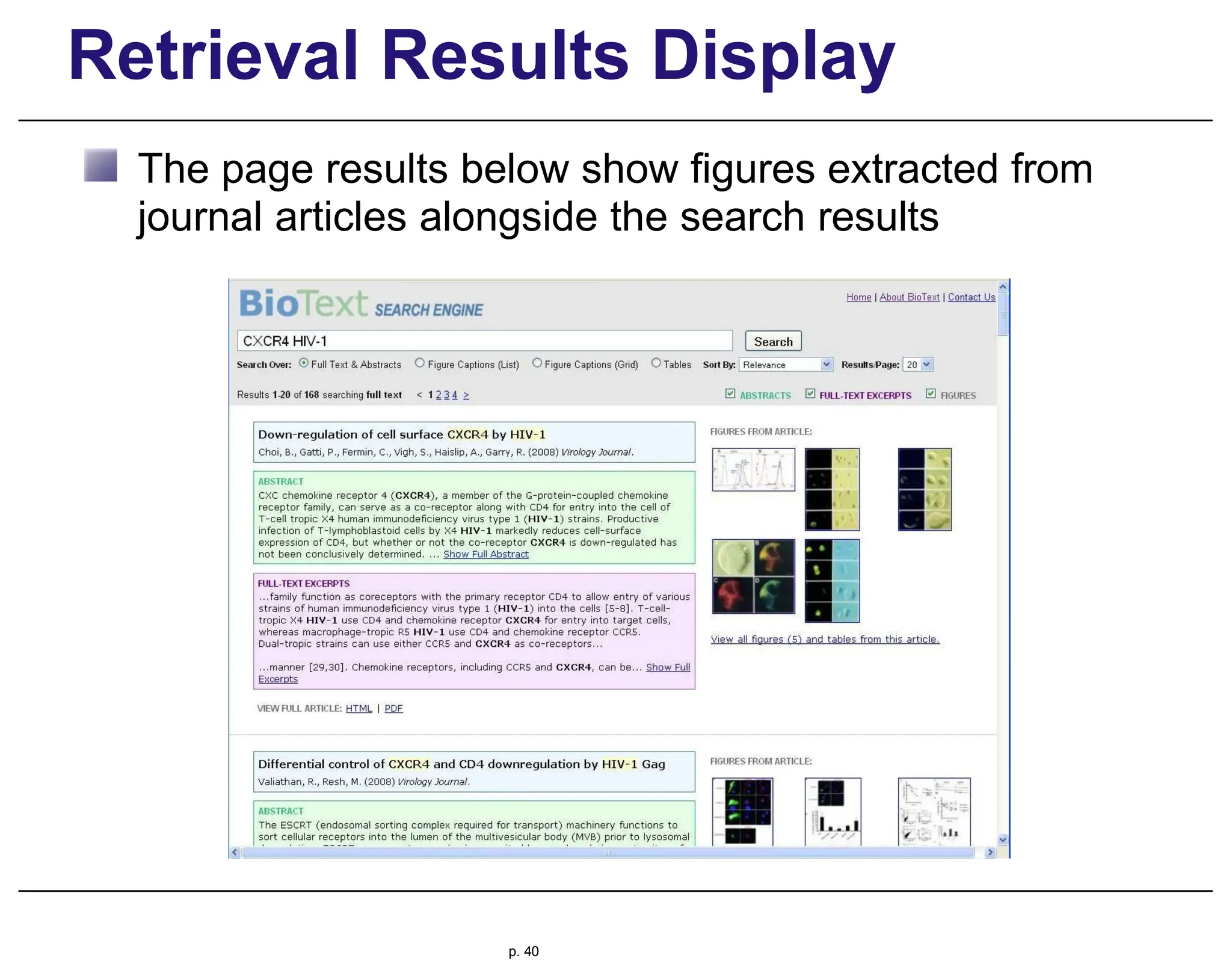

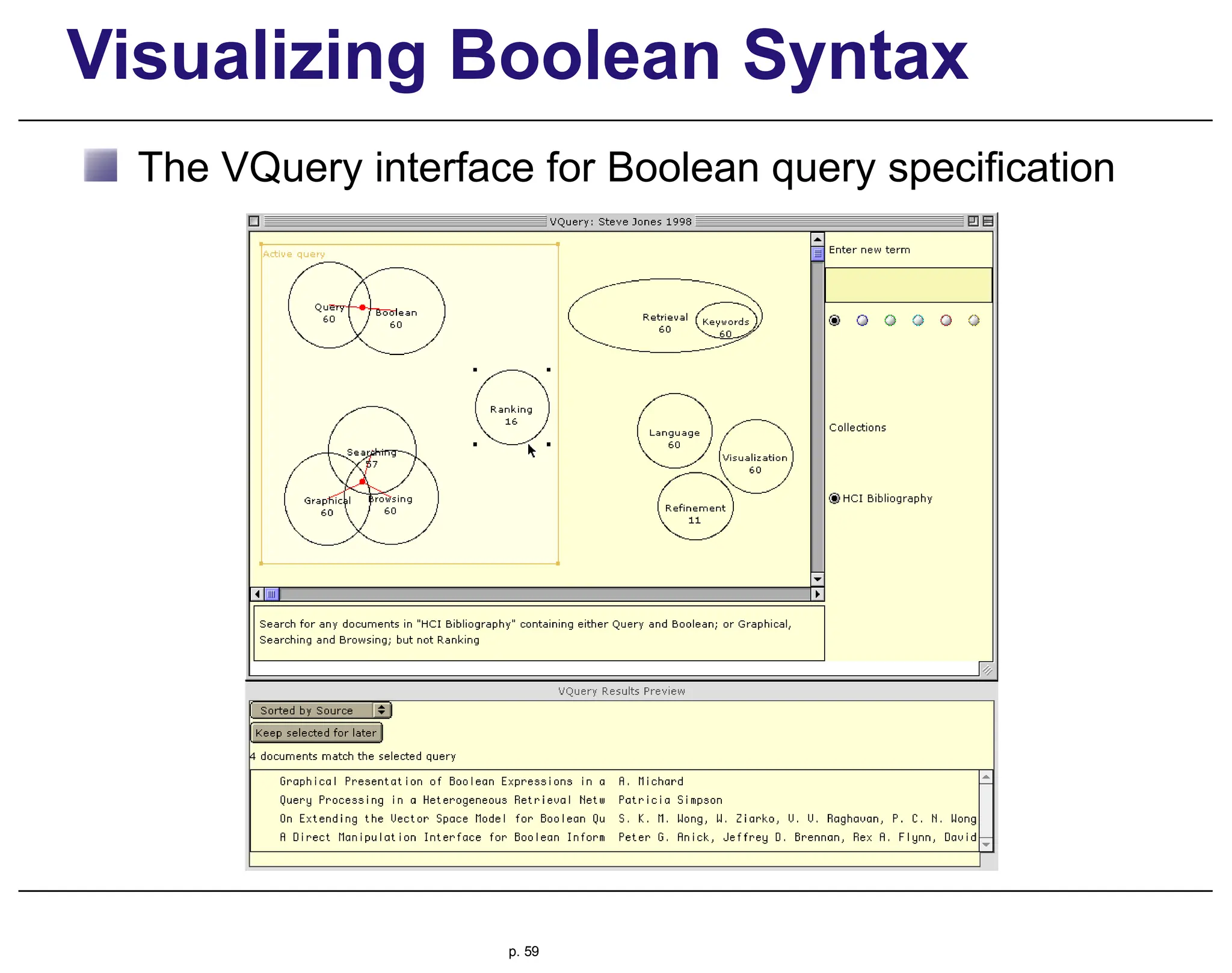

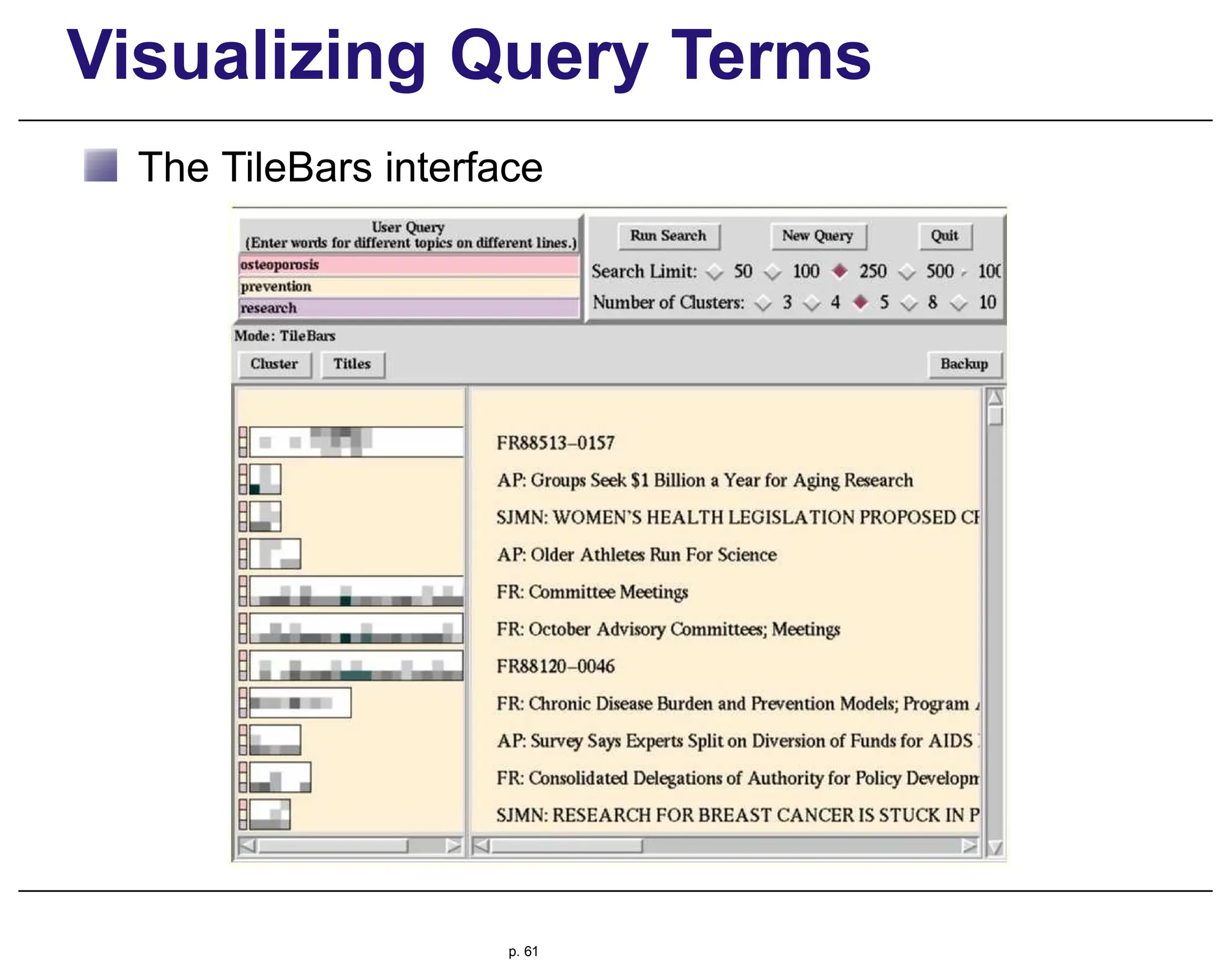

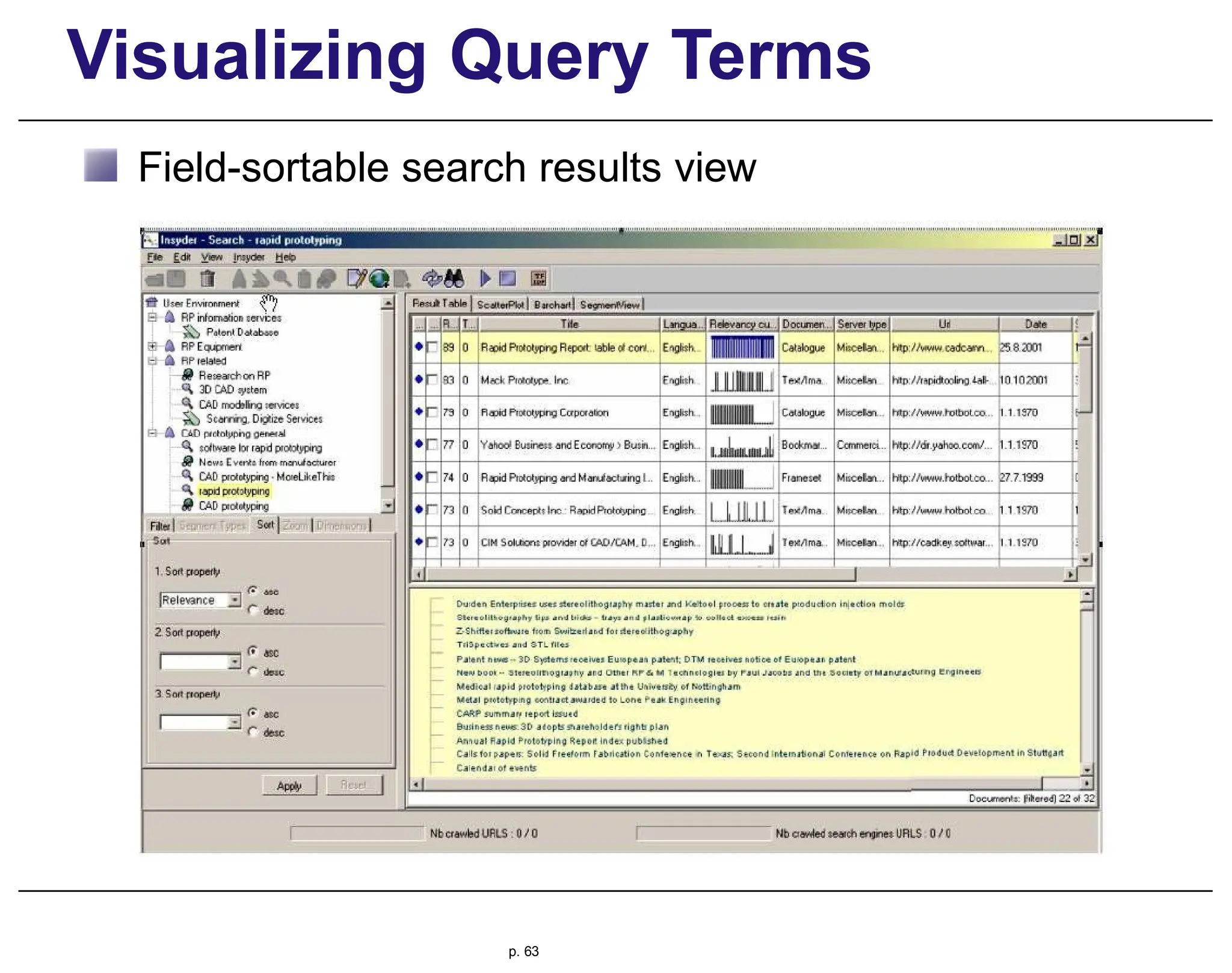

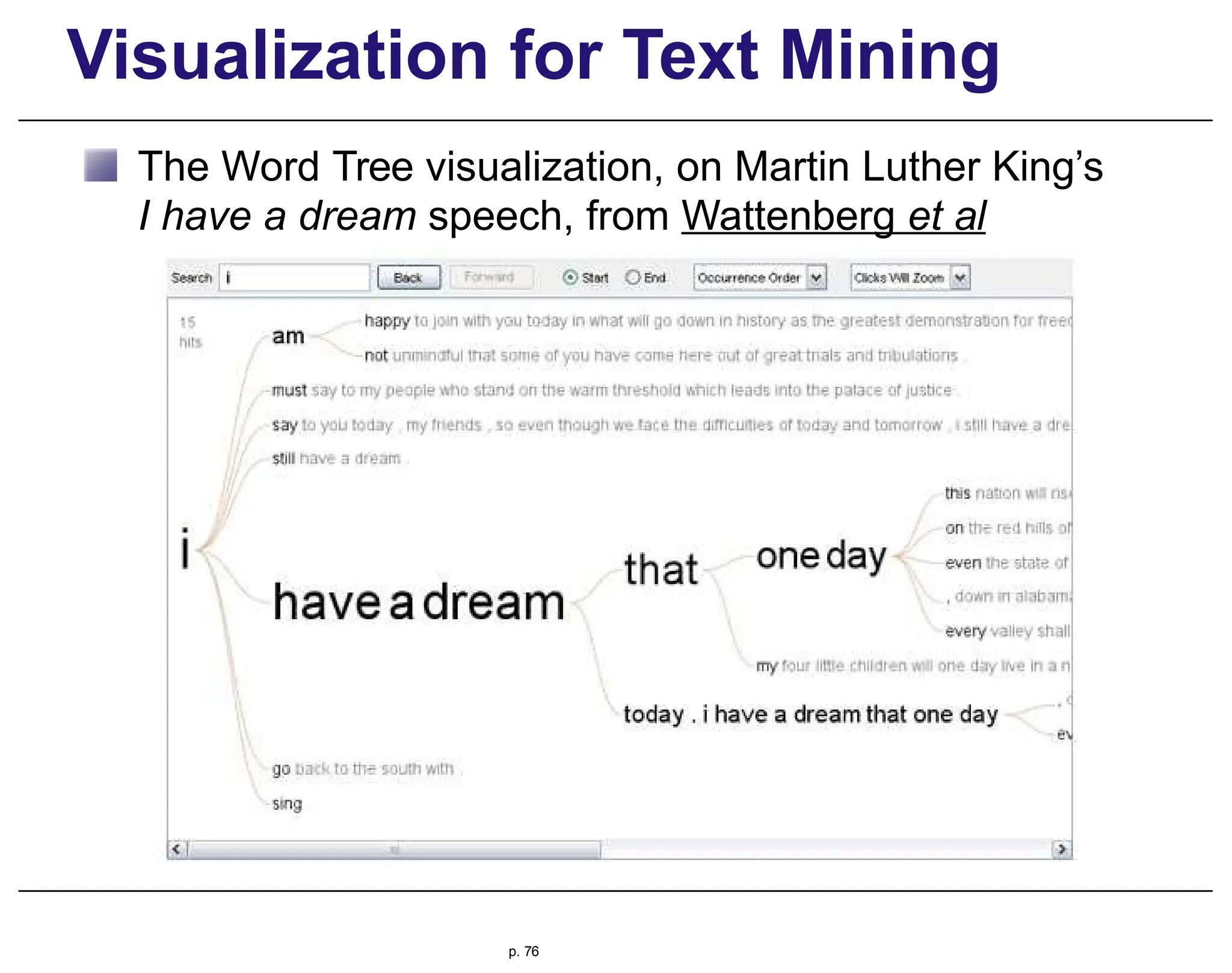

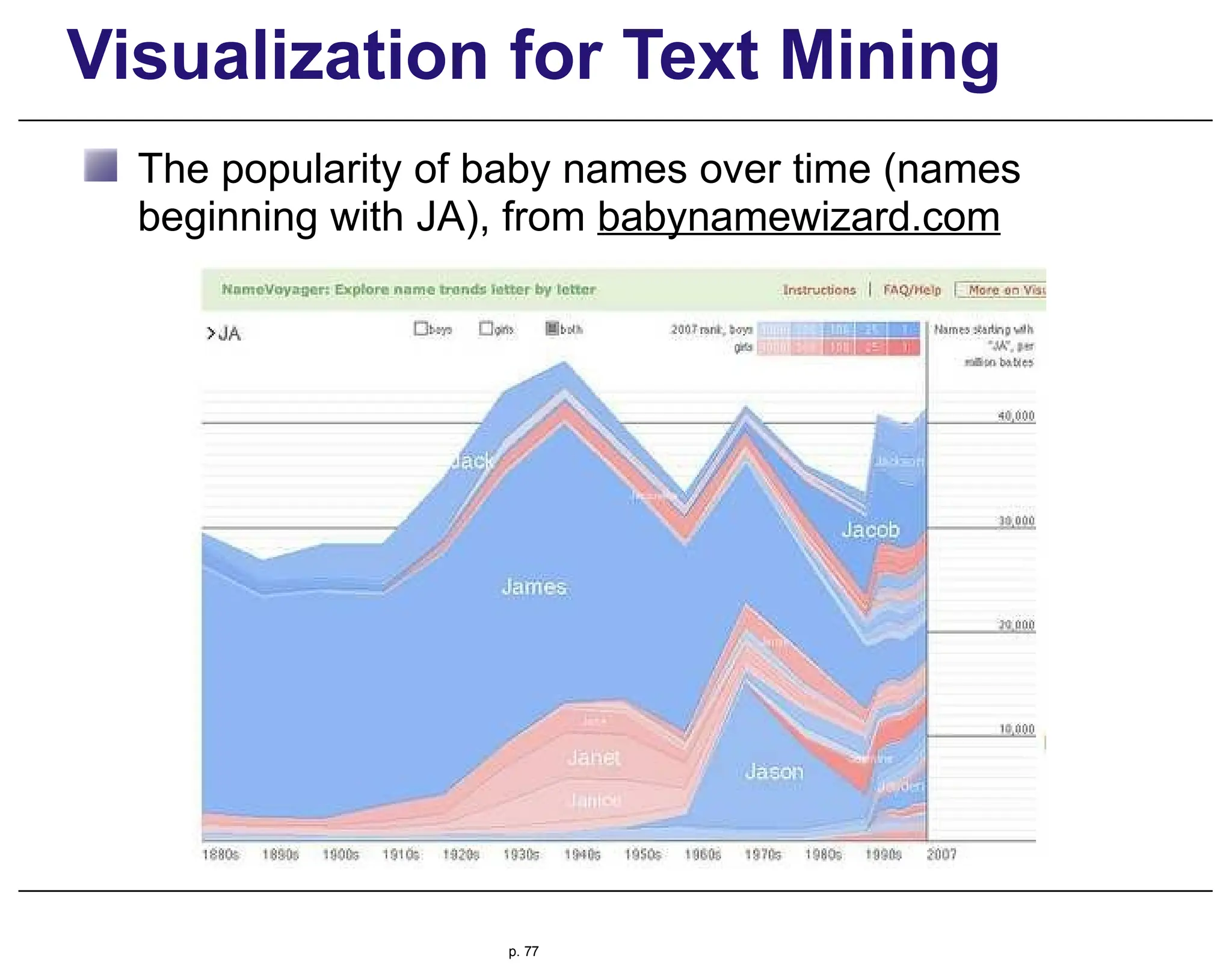

This document provides an overview of information retrieval (IR), discussing its history, techniques, and importance in the context of the web. It details the evolution of IR from manual indexing and library systems to modern automated processes and highlights the challenges and changes brought about by the web era. The text addresses the user experience in information seeking, emphasizing the role of query formulation and interface design in meeting user needs.