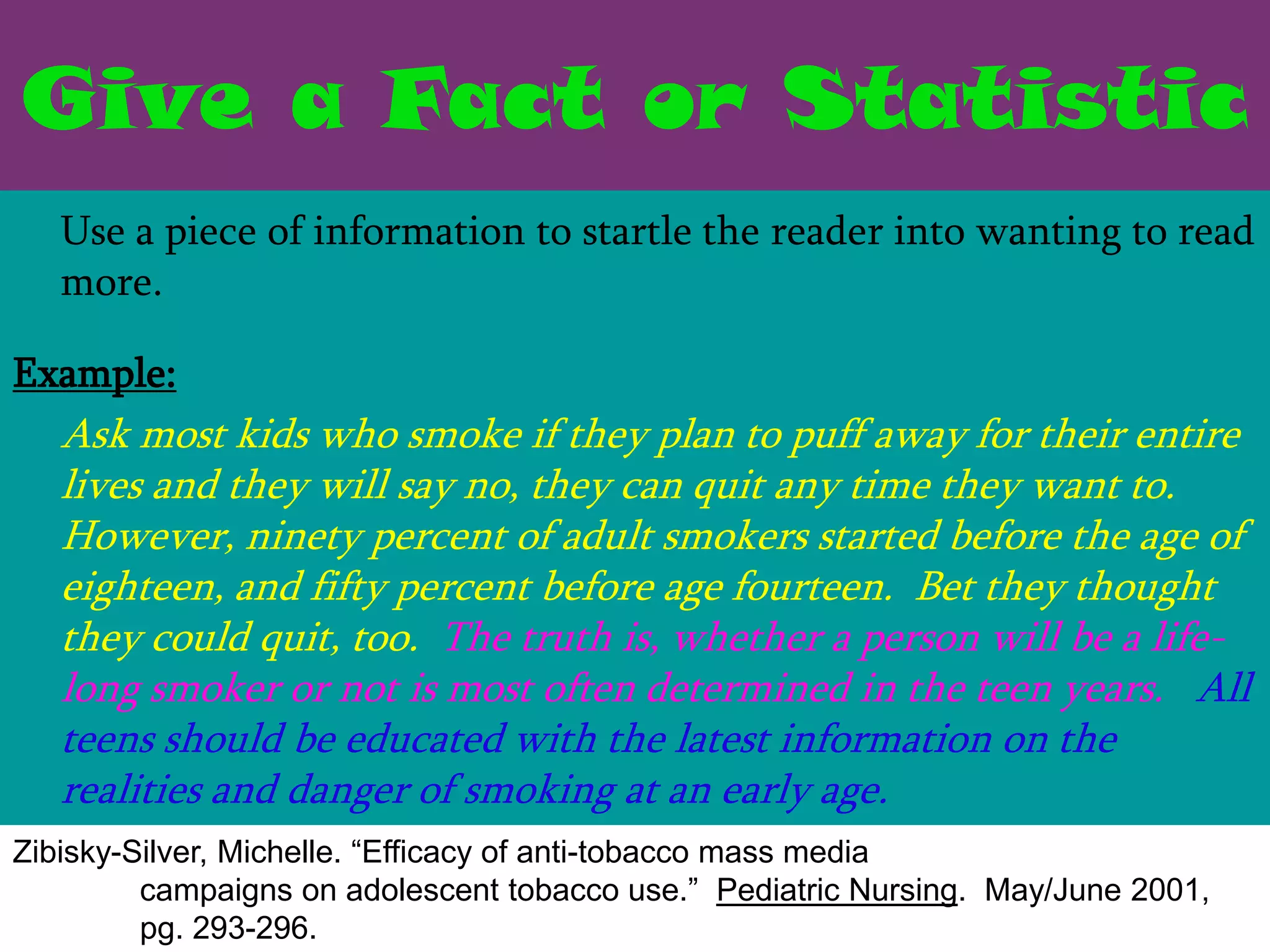

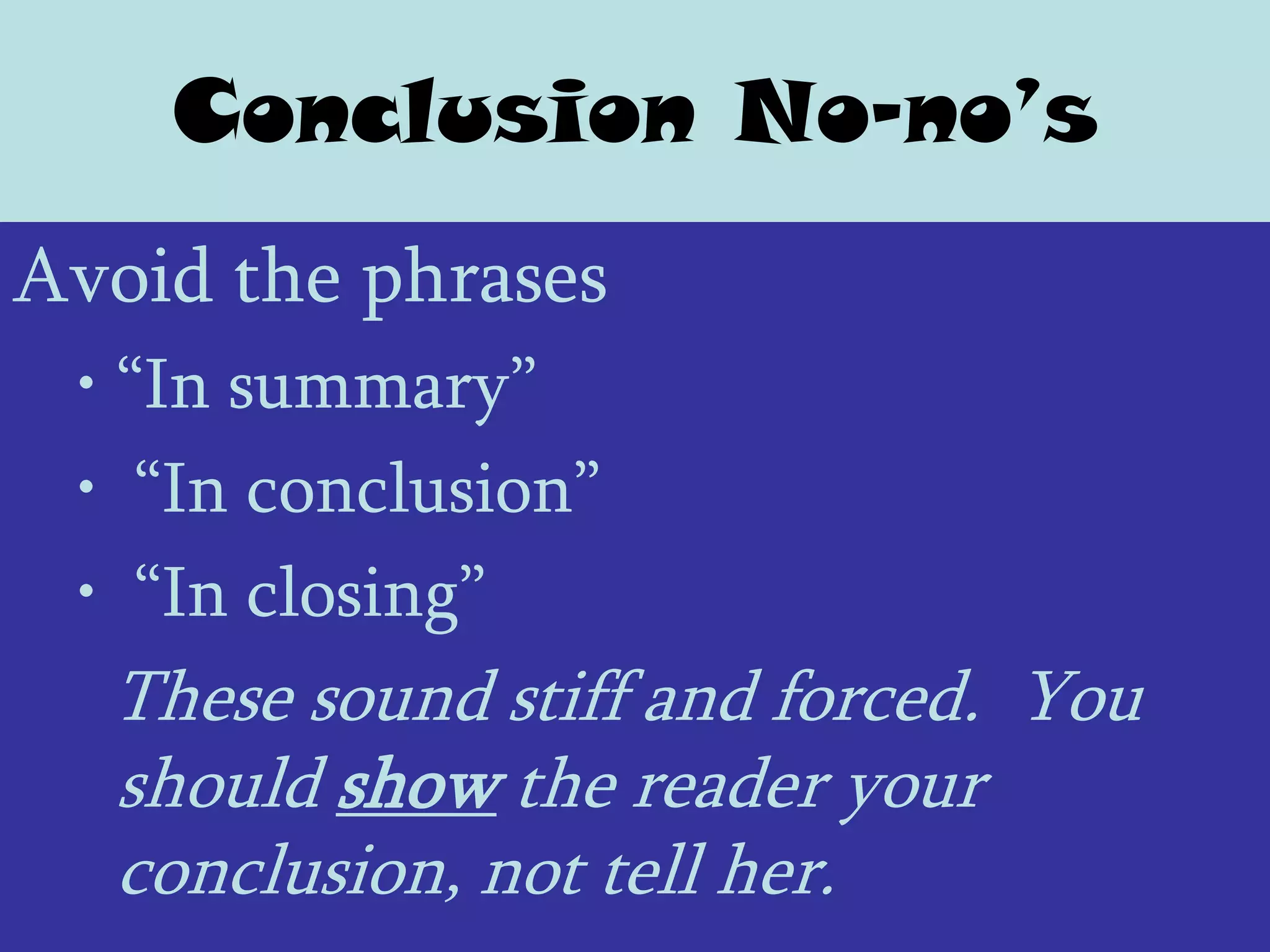

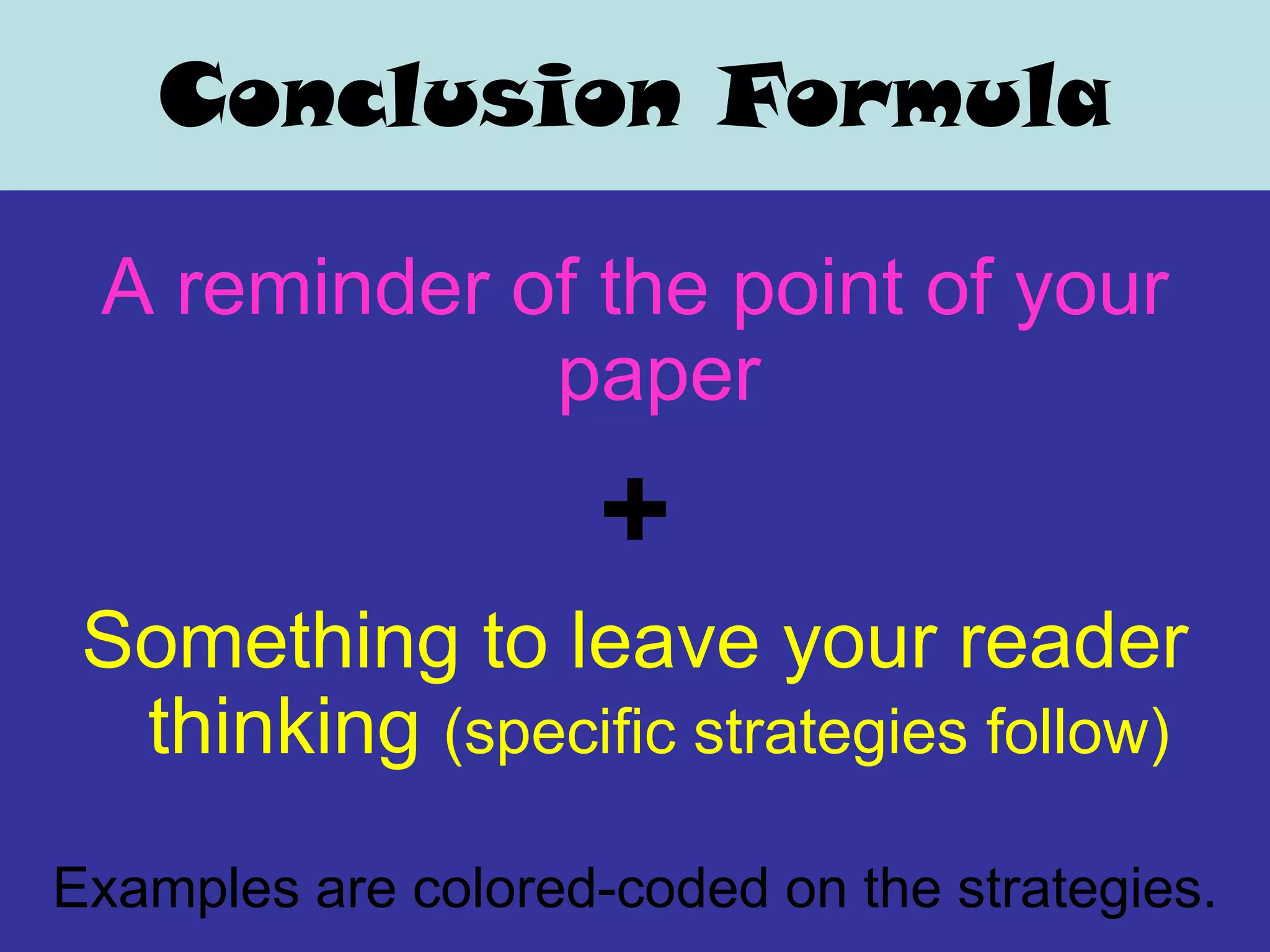

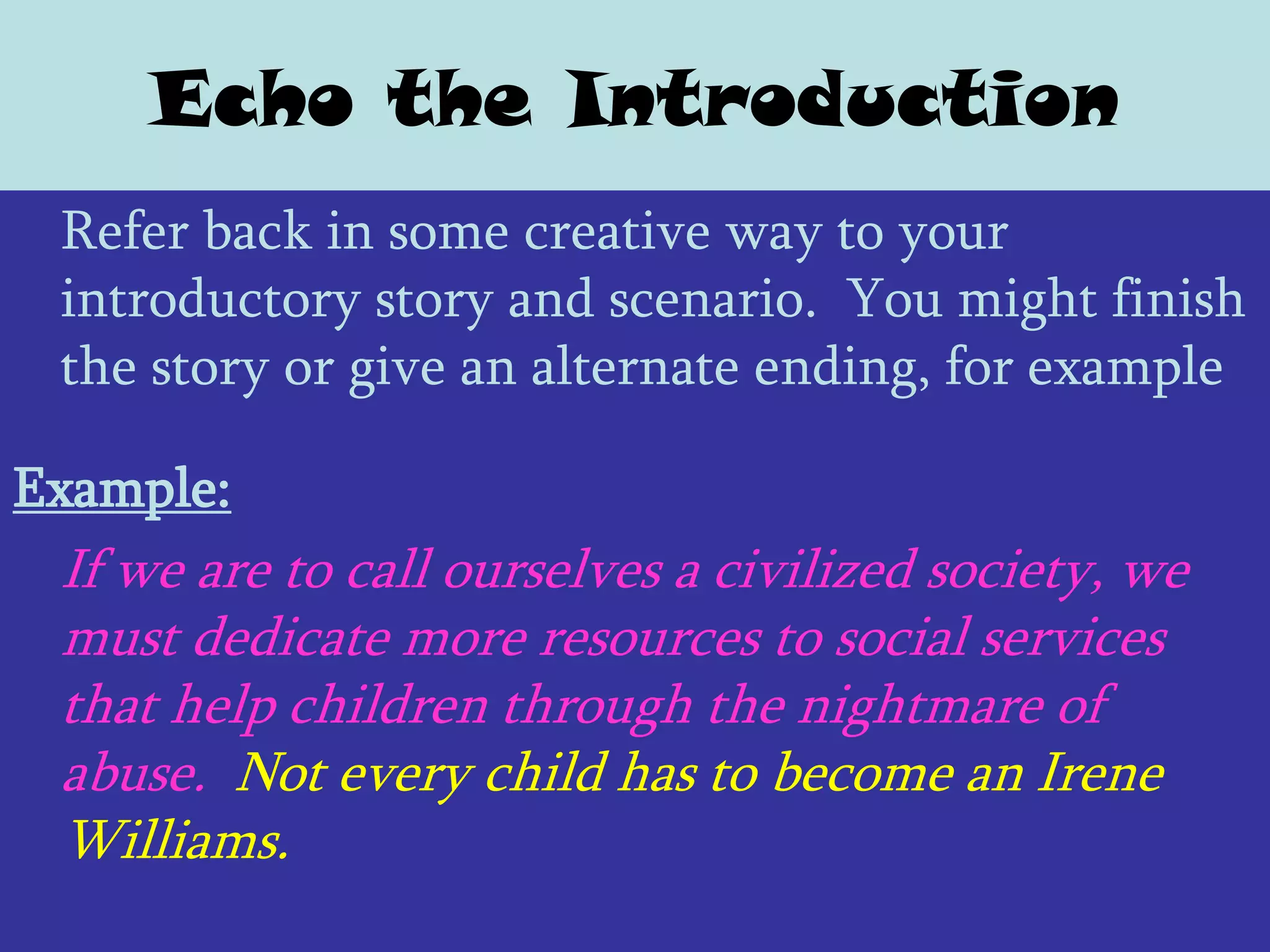

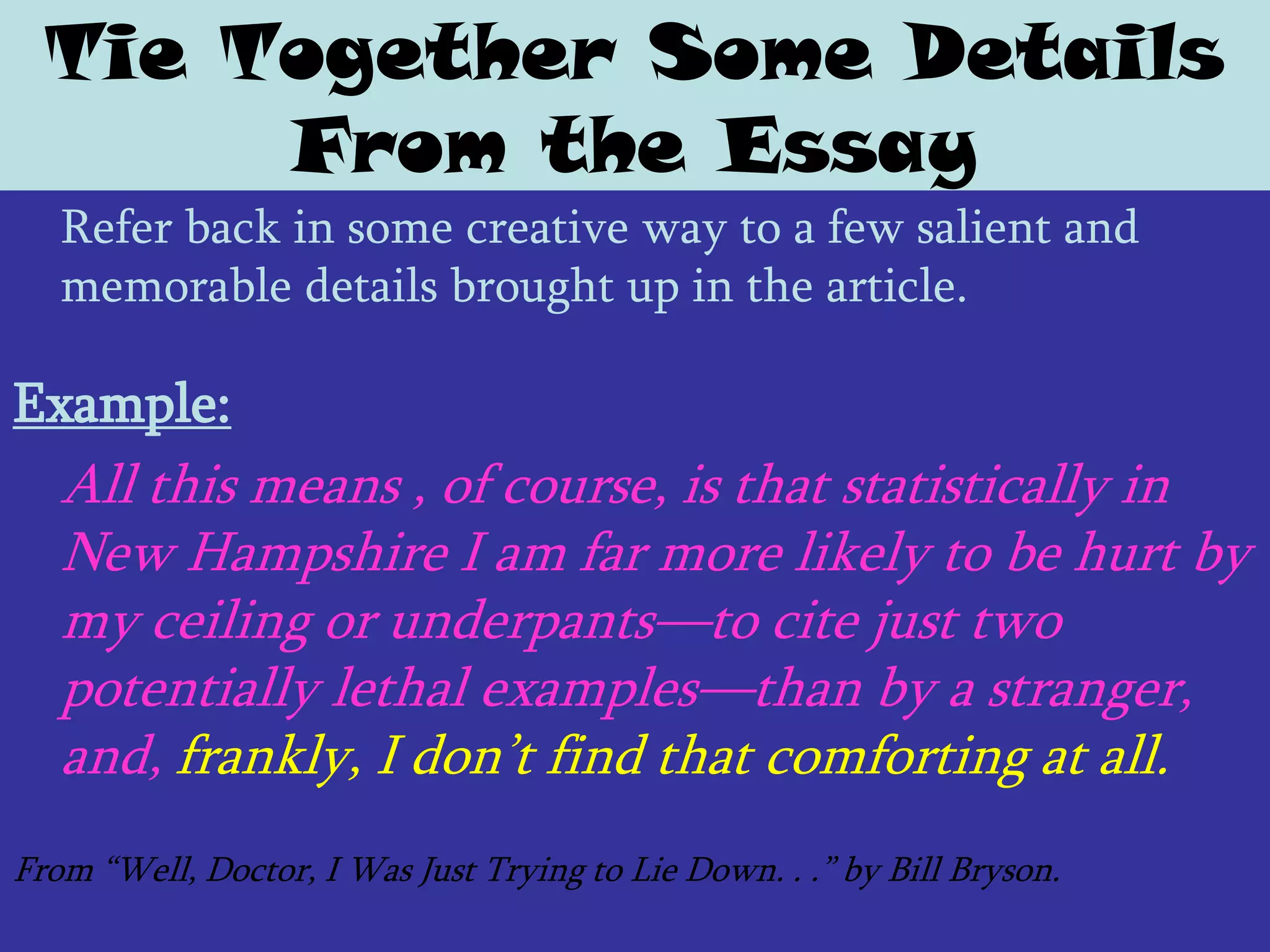

The document provides strategies for writing effective introductions and conclusions to essays. It begins by explaining that introductions should catch the reader's attention and introduce the thesis. Several introduction strategies are then presented with examples, including telling a story, asking questions, using a theme statement, or providing background information. The document concludes by stating that conclusions should stress the main point and leave a final impression, and provides strategies like echoing the introduction or tying together essay details.

![Use a Quotation

Find a relevant quote from a source of authority.

Example:

"The novel Lolita," the critic Charles Blight said in 1959,

"is proof that American civilization is on the verge of

total moral collapse" (45). The judgment of critics and

readers in subsequent years, however, has proclaimed

Lolita [is/to be] one of the greatest love stories of all time

and one of the best proofs that American civilization is

still vibrant and alive.

“Introduction Strategies.” MIT Online Writing and Communication Center. Massachusetts

Institute of Technology, 2001.

<http://web.mit.edu/writing/Writing_Types/introstrategies.html>](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/introductionsandconclusions-111130162110-phpapp02/75/Introductions-and-Conclusions-14-2048.jpg)