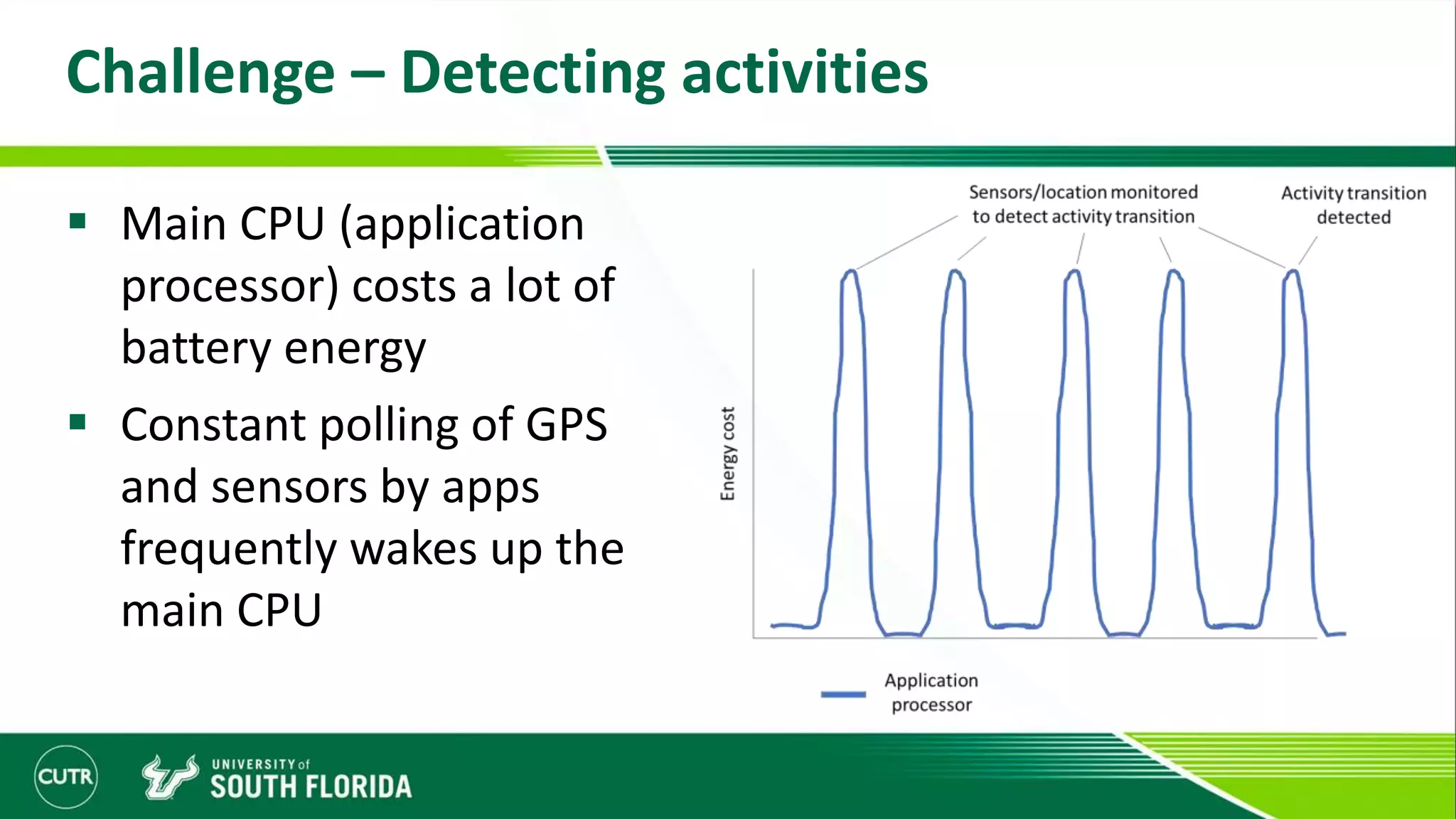

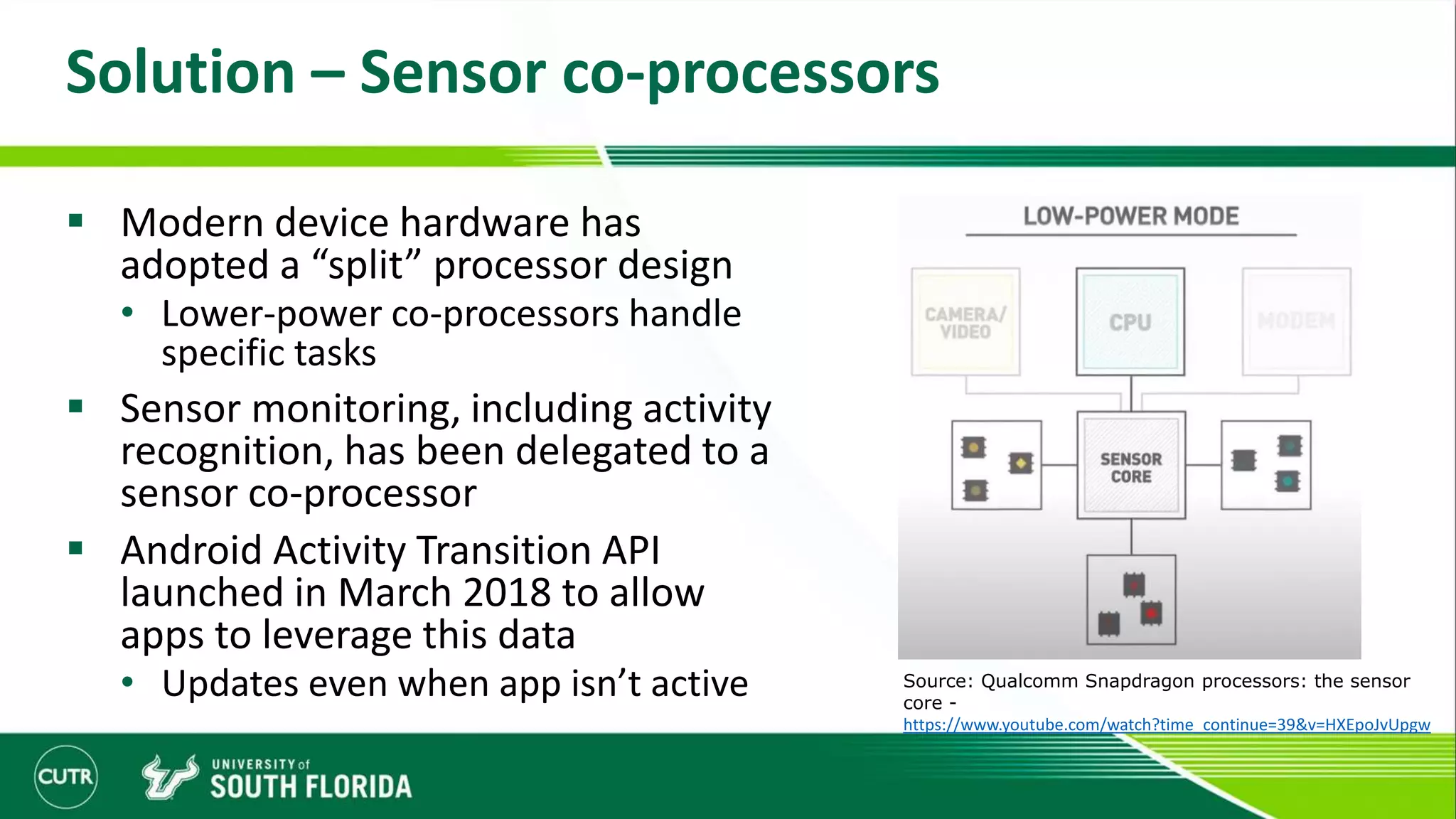

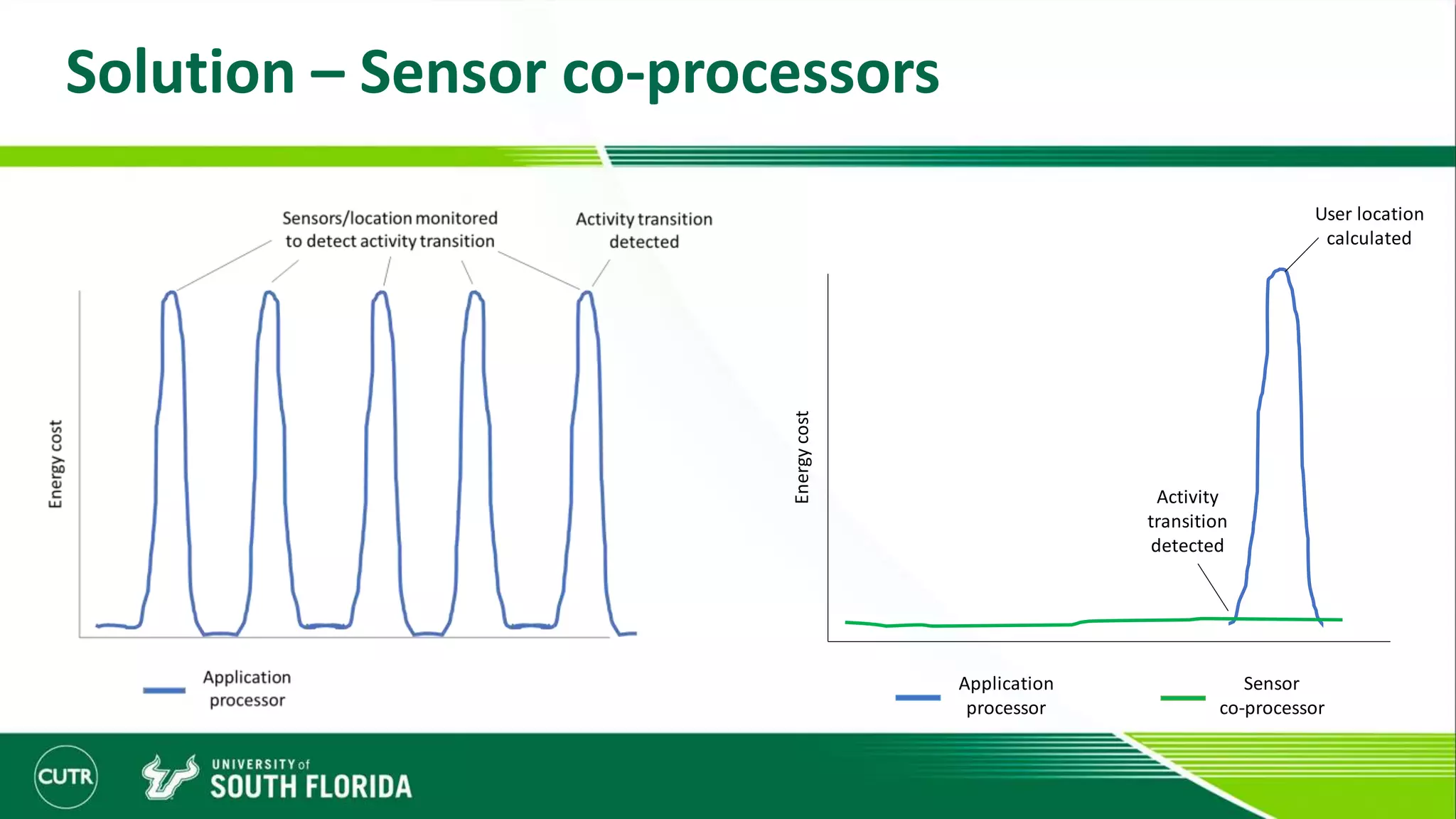

The document discusses a project aimed at improving the quality and cost-effectiveness of multimodal travel behavior data collection, addressing limitations in current methods such as manual trip recording and app-based fatigue. The solution involves leveraging an open-source platform called OneBusAway, which uses sensor co-processors in mobile devices to accurately capture user activities and collect data without significantly impacting battery life. Preliminary findings suggest successful data collection with minimal user fatigue and acceptable accuracy, showcasing the promise of app-based transitions for further transportation studies.

![Challenge – Recruiting and retaining subjects

Past mobile apps have been created specifically to replace travel

behavior surveys:

• TRAC-IT [1]

• Future Mobility Survey [2]

• Quantified Traveler[3]

• SmarTrAC [4]

• Florida Trip Tracker[5]

These apps all suffer from user fatigue from manually recorded trips

and have only been deployed in small research settings

• No ongoing incentive or value to user for using app

• Negative impacts on battery life

[1] Philip L. Winters, Sean J. Barbeau, and Nevine L. Georggi (2008). "Smart Phone Application to Influence Travel Behavior (TRAC-IT Phase 3)," National Center for Transit Research.

[2] C; Pereira Cottrill, F.; Zhao, F.;Dias,I.; Lim, H. B. ;Ben-Akiva, M.;Zegra, C. (2013), "Future Mobility Survey: Experience in Developing a Smart-Phone-Based Travel Survey in Singapore," Transportation Research Record, pp. 59-67.

[3] Jerald; Abou-Zeid Jariyasunant, Maya; Carrel, Andre;Ekambaram, Venkatesan (2019), "Quantified Traveler: Travel Feedback Meets the Cloud to Change Behavior," Journal of Intelligent Transportation Systems, Vol. 19 pp. 1-16.

[4] Yingling ; Wolfson Fan, Julian ;Adomavicius,Gediminas ; Das, Kirti V; Khandelwal, Yash ;Kang,Jie (2015). "SmarTrAC: A Smartphone Solution for Context-Aware Travel and Activity Capturing," University of Minnesota, February 2015.

[5] AECOM Tallahassee. "Florida Trip Tracker." Accessed December 11, 2019 from https://play.google.com/store/apps/details?id=com.urs.triptracks](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/improvingthequalityandcosteffectivenessofmultimodaltravelbehaviordatacollection-v2-200424143545/75/Improving-the-quality-and-cost-effectiveness-of-multimodal-travel-behavior-data-collection-6-2048.jpg)

![Solution - OneBusAway

An open-source platform for real-time transit information

Supported by the Open Transit Software Foundation, a 501(c)3 non-profit

• Includes transit agencies, universities, consultants, and independent

developers

Deployed by agencies in 11 cities worldwide

Agencies see advantages to pooling resources to implement similar rider-

facing features[6]

For iOS and Android (not including web, SMS, IVR, Alexa):

• Over 1 million unique users

• Typically ~330k active users in the last 30 days

Hundreds of thousands more when including web and white-label

deployments

Platform for research (users can opt-in)

onebusaway.org

[6] Sean J. Barbeau, Steven Polzin. “Open Source Software in Public Transportation: A Case Study,” Presented at the

Transportation Research Board (TRB) 99th Annual Meeting, Washington, D.C., January 12-16, 2020.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/improvingthequalityandcosteffectivenessofmultimodaltravelbehaviordatacollection-v2-200424143545/75/Improving-the-quality-and-cost-effectiveness-of-multimodal-travel-behavior-data-collection-7-2048.jpg)