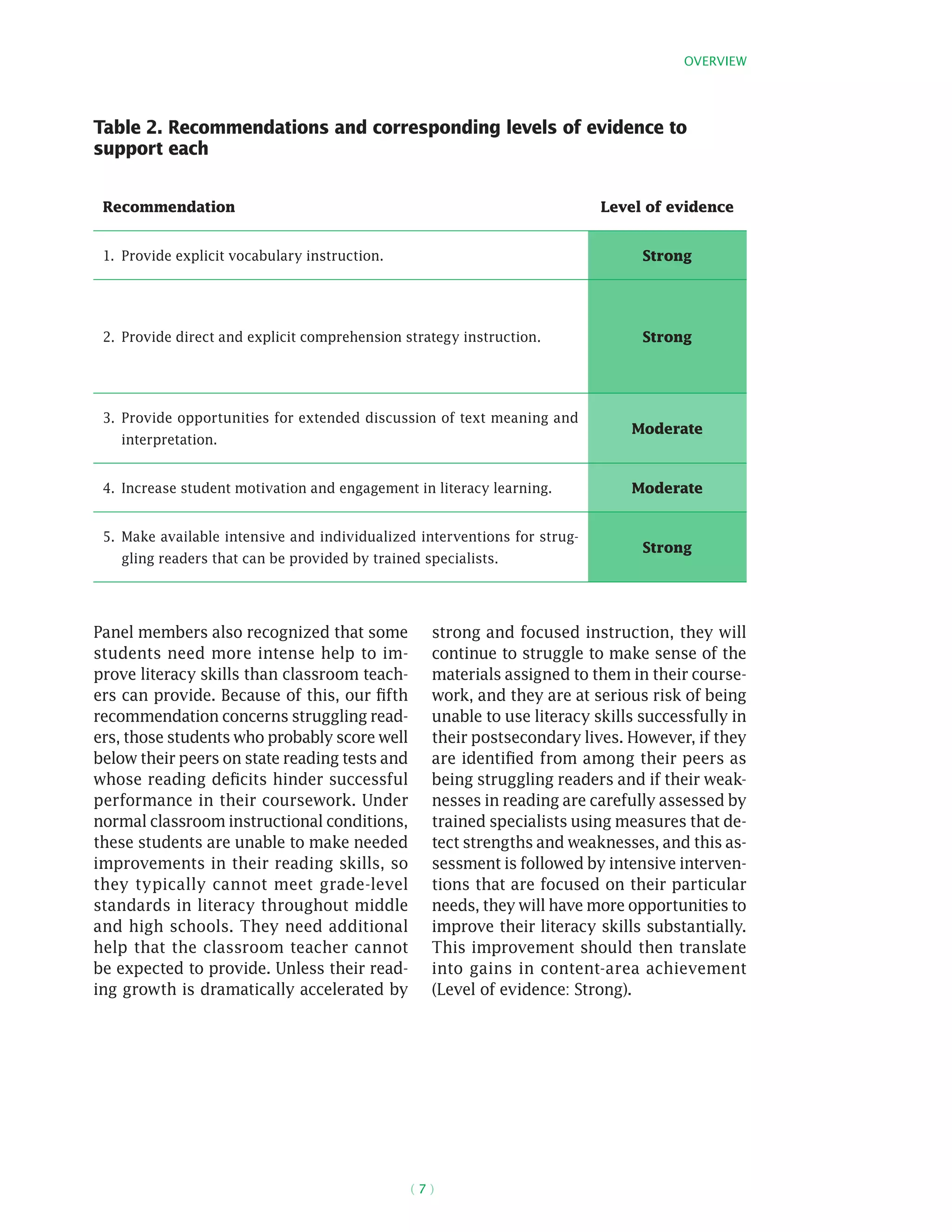

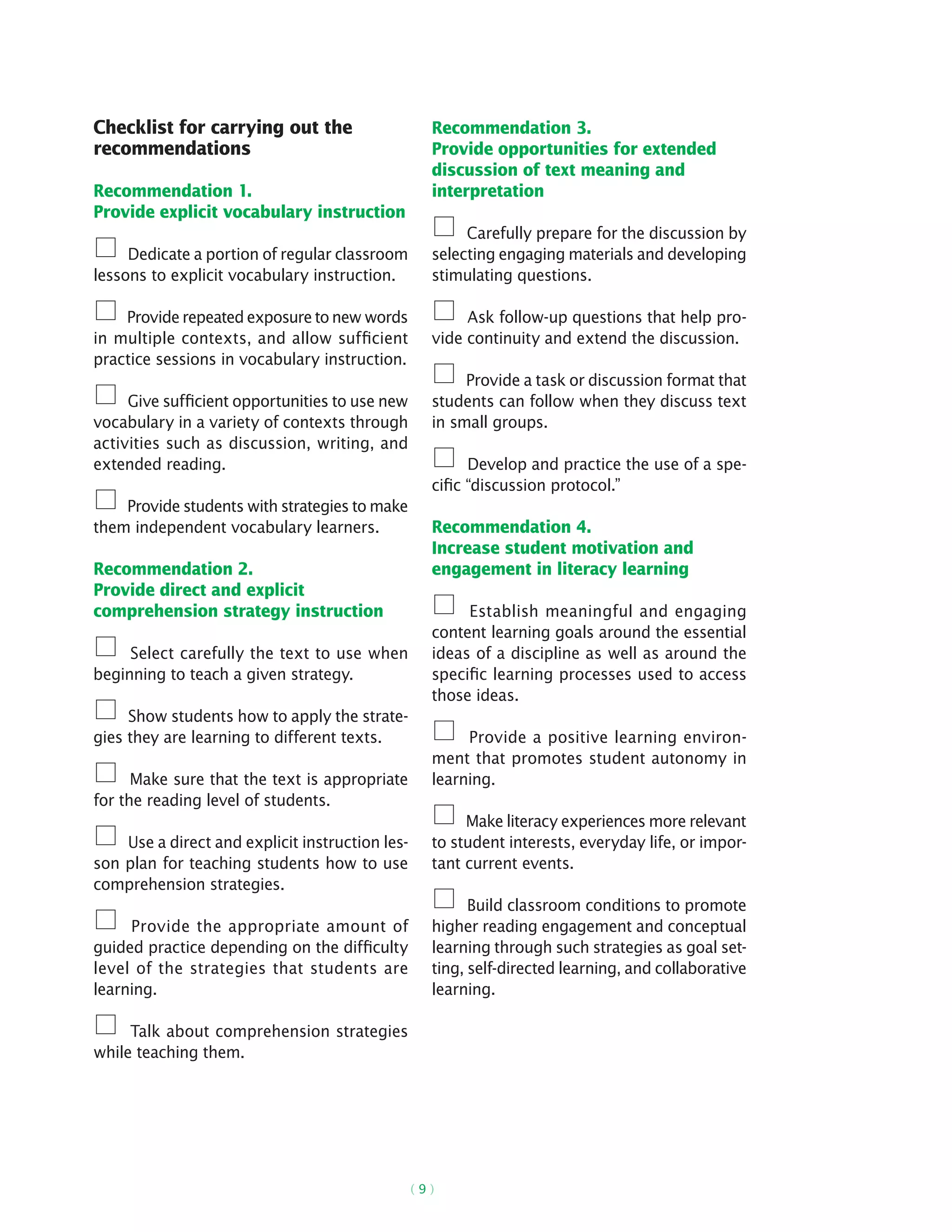

This document presents recommendations for improving adolescent literacy based on an analysis of research evidence. It aims to provide teachers and other school staff with practical strategies supported by various studies. The recommendations target students in upper elementary through high school. They address vocabulary instruction, comprehension strategies, discussion of texts, increasing student motivation and engagement, and interventions for struggling readers. Each recommendation is accompanied by a discussion of the strength of the evidence backing it, which can be strong, moderate, or low. The goal is to help educators select practices that have the best chance of boosting literacy skills.