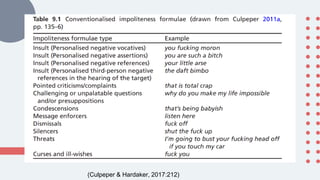

The document discusses the concept of impoliteness in communication, emphasizing that impoliteness strategies are designed to attack face and disrupt social equilibrium. It outlines developments in the study of linguistic impoliteness, categorizing it into three waves: classic politeness models, interactional approaches, and discursive approaches, highlighting the complexity of impoliteness based on context and speaker intent. Finally, it suggests that future research should integrate both politeness and impoliteness within interpersonal communication to better understand their dynamics.

![“[The role of the Politeness Principle is] "to maintain the social equilibrium

and the friendly relations which enable us to assume that our

interlocutors are being cooperative in the first place." (Leech, 1983: 82)

"... politeness, like formal diplomatic protocol (for which it must surely be

the model), presupposes that potential for aggression as it seeks to

disarm it, and makes possible communication between potentially

aggressive parties." (Brown and Levinson, 1987: 1)

"Politeness can be defined as a means of minimizing confrontation in

discourse- both the possibility of confrontation occurring at all, and the

possibility that a confrontation will be perceived as threatening."

(Lakoff, 1989: 102)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/12impoliteness-241222113642-8e2e185a/85/Impoliteness-Semantic-Pragmatics-Language-2-320.jpg)

![Definition: Intention

Impoliteness constitutes the communication of intentionally

gratuitous and conflictive verbal face-threatening acts which are

purposefully delivered: (1) unmitigated […], and /or (ii) with

deliberate aggression […].

(Bousfield, 2008:72)

Impoliteness comes about when: (1) the speaker communicates

face-attack intentionally, or (2) the hearer perceives behaviour as

intentionally face-attacking, or a combination of (1) and (2).

(Culpeper, 2005:38)

The

speaker's

perceptions

of

intentionality

The

speaker’s

and the

hearer’s

perceptions

of

intentionality

full intentionality is not a

necessary condition of

impoliteness](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/12impoliteness-241222113642-8e2e185a/85/Impoliteness-Semantic-Pragmatics-Language-7-320.jpg)

![Mock Impoliteness

● Mock impoliteness or banter, is impoliteness that

remains on the surface, since it is understood that

it is not intended to cause offence.

● I once turned up late for a party, and upon

explaining to the host that I had mistaken 17.00

hours for 7 o'clock, I was greeted with a smile and

the words "You silly bugger"

Leech's (1983) Banter Principle:

"In order to show solidarity with h, say something

which is (i) obviously untrue, and (ii) obviously

impolite to h" [and this will give rise to an

interpretation such that] "what s says is impolite to h

and is clearly untrue. Therefore, what s really means

is polite to h and true." (1983: 144)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/12impoliteness-241222113642-8e2e185a/85/Impoliteness-Semantic-Pragmatics-Language-12-320.jpg)

![Too many theories (cf. Brown and Levinson, 1987 [1978];

Lachenicht, 1980; and Leech,

1983) consider impoliteness within the context of a single turn

at talk.

They do not adequately describe, nor predict, how

(im)politeness may be used by speakers in extended, real-life

interactions.

Investigating the phenomena of impoliteness in the fuller

context of extended discourse as it is understood, schematically,

by the participants (cf. Terkourafi, 2005) has significant

contributions to make.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/12impoliteness-241222113642-8e2e185a/85/Impoliteness-Semantic-Pragmatics-Language-27-320.jpg)