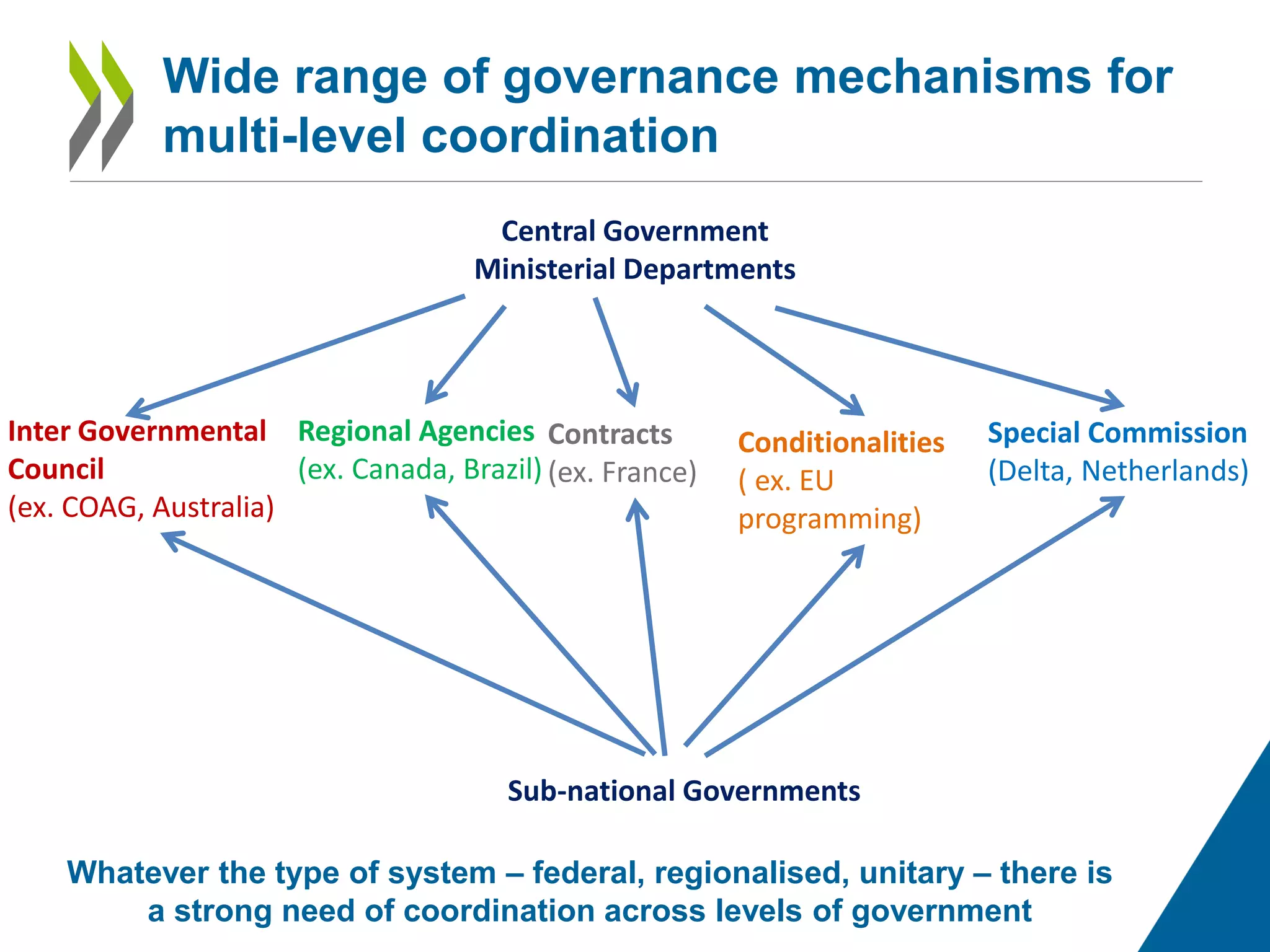

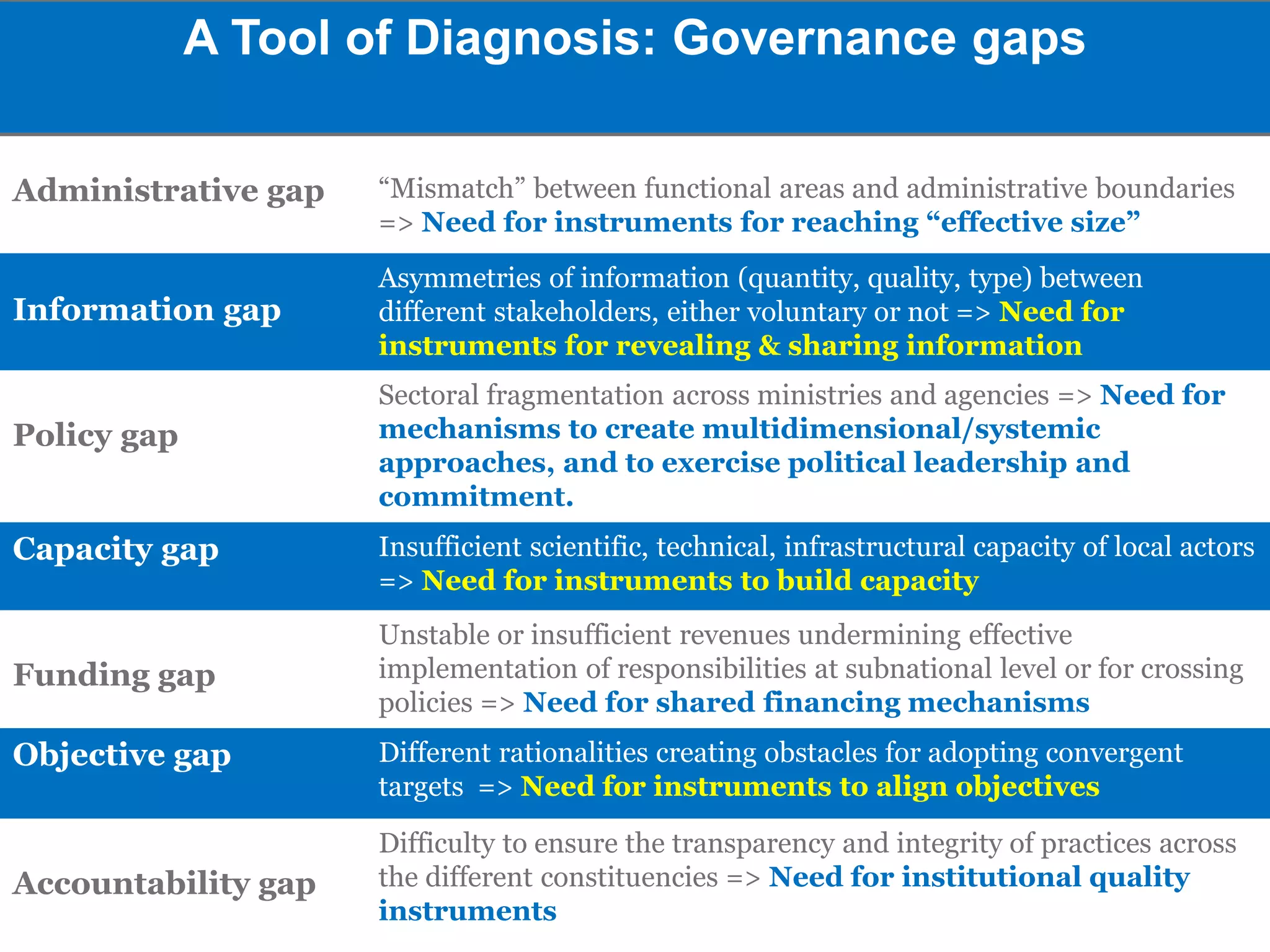

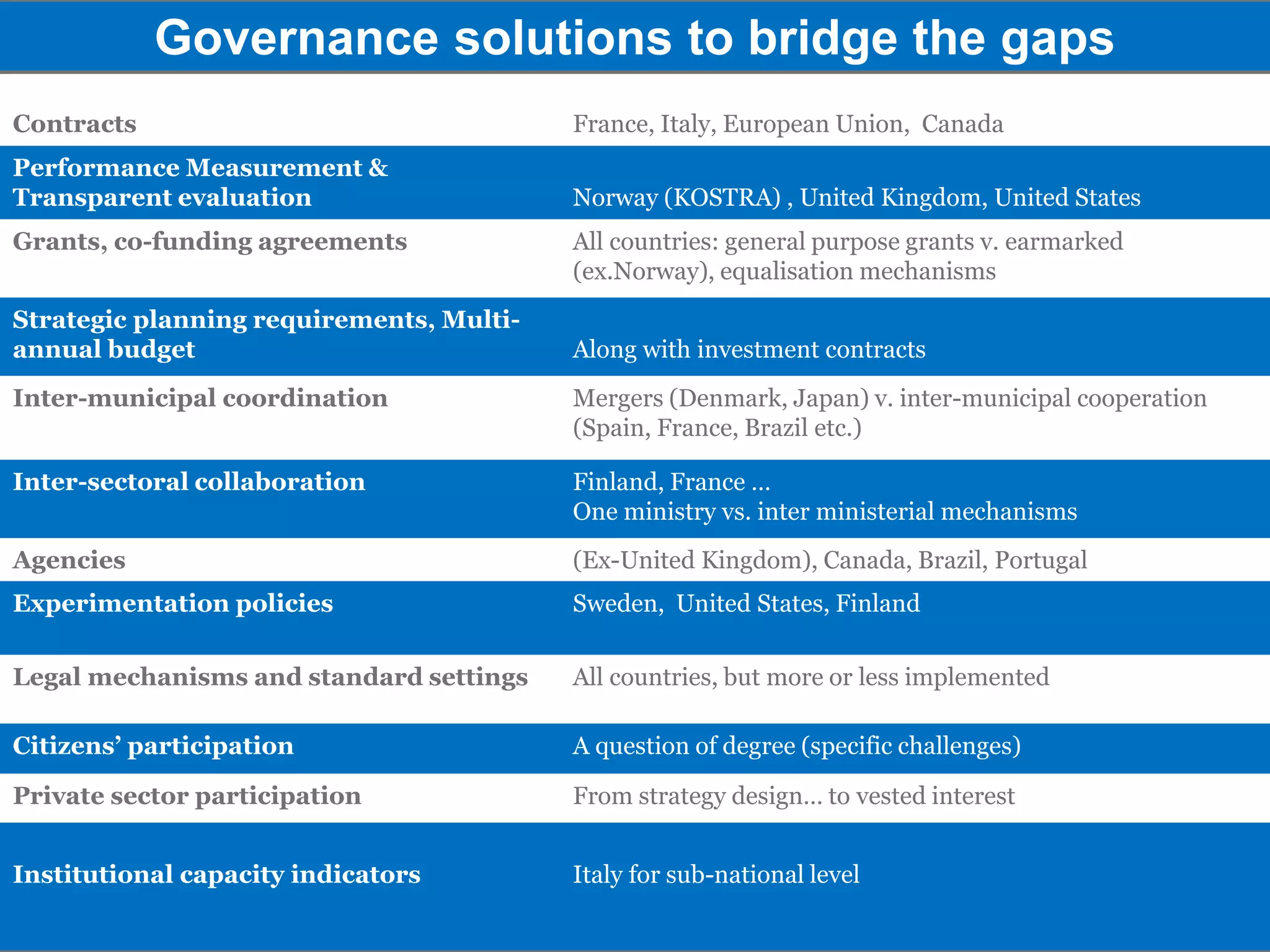

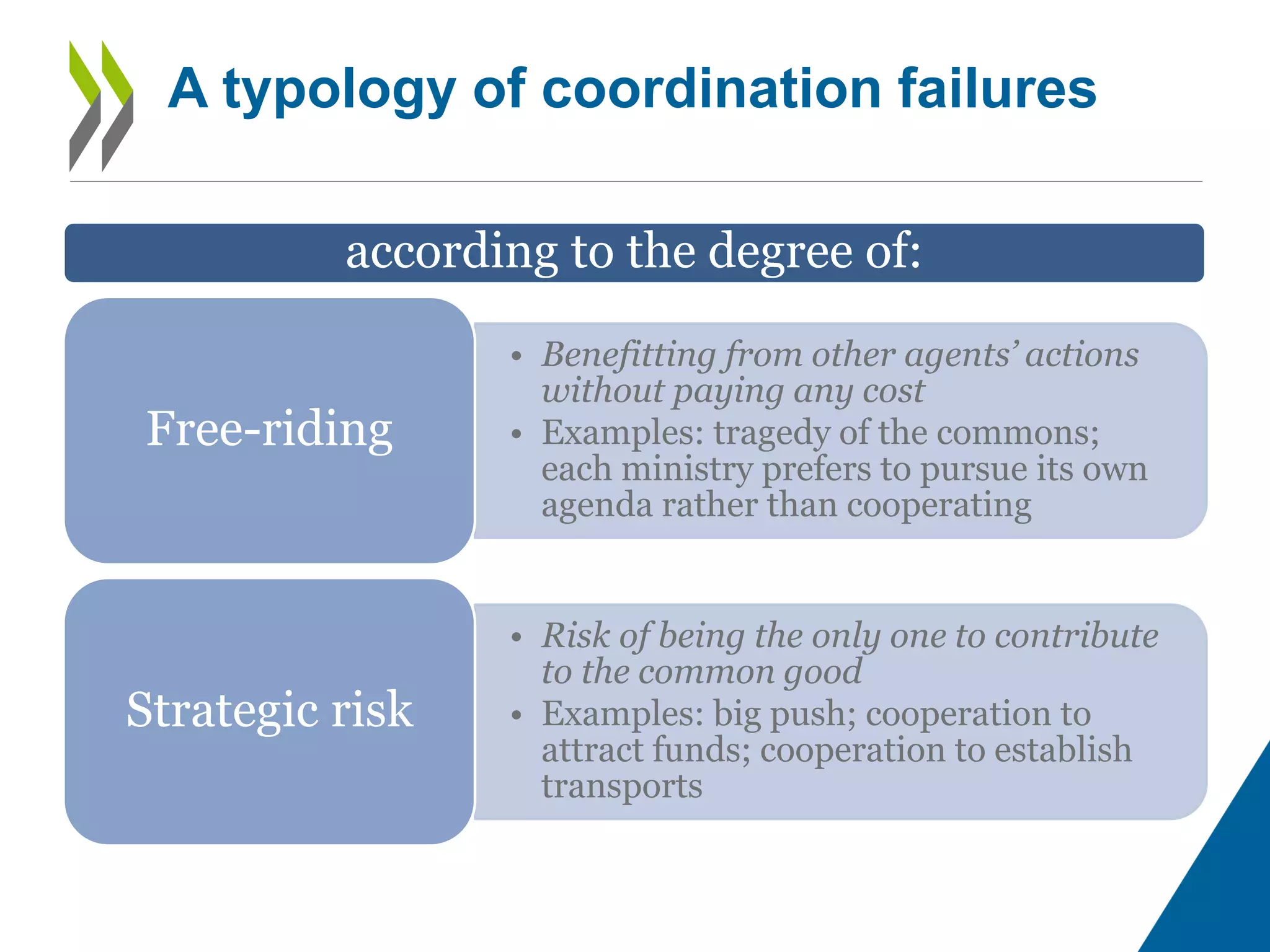

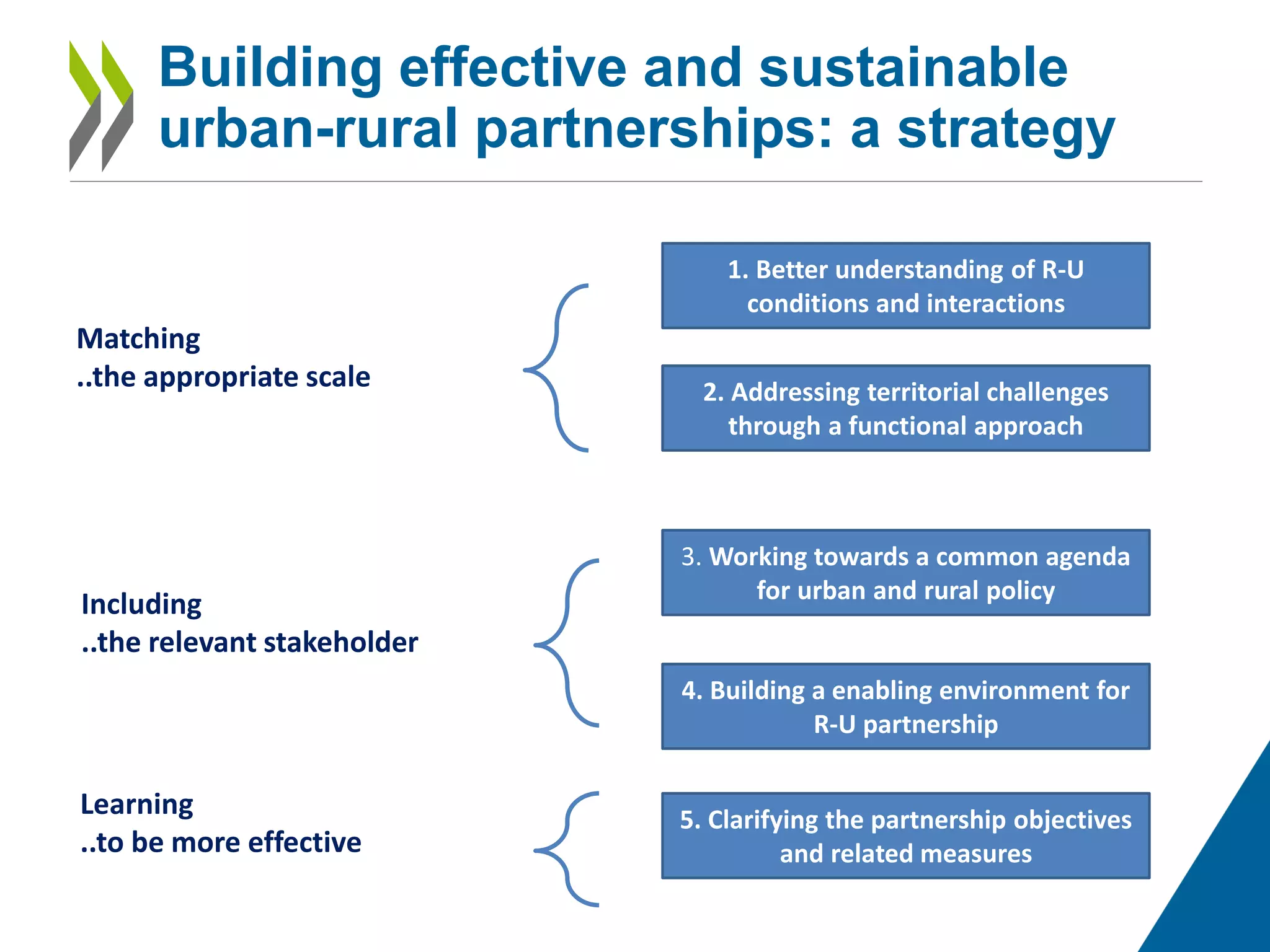

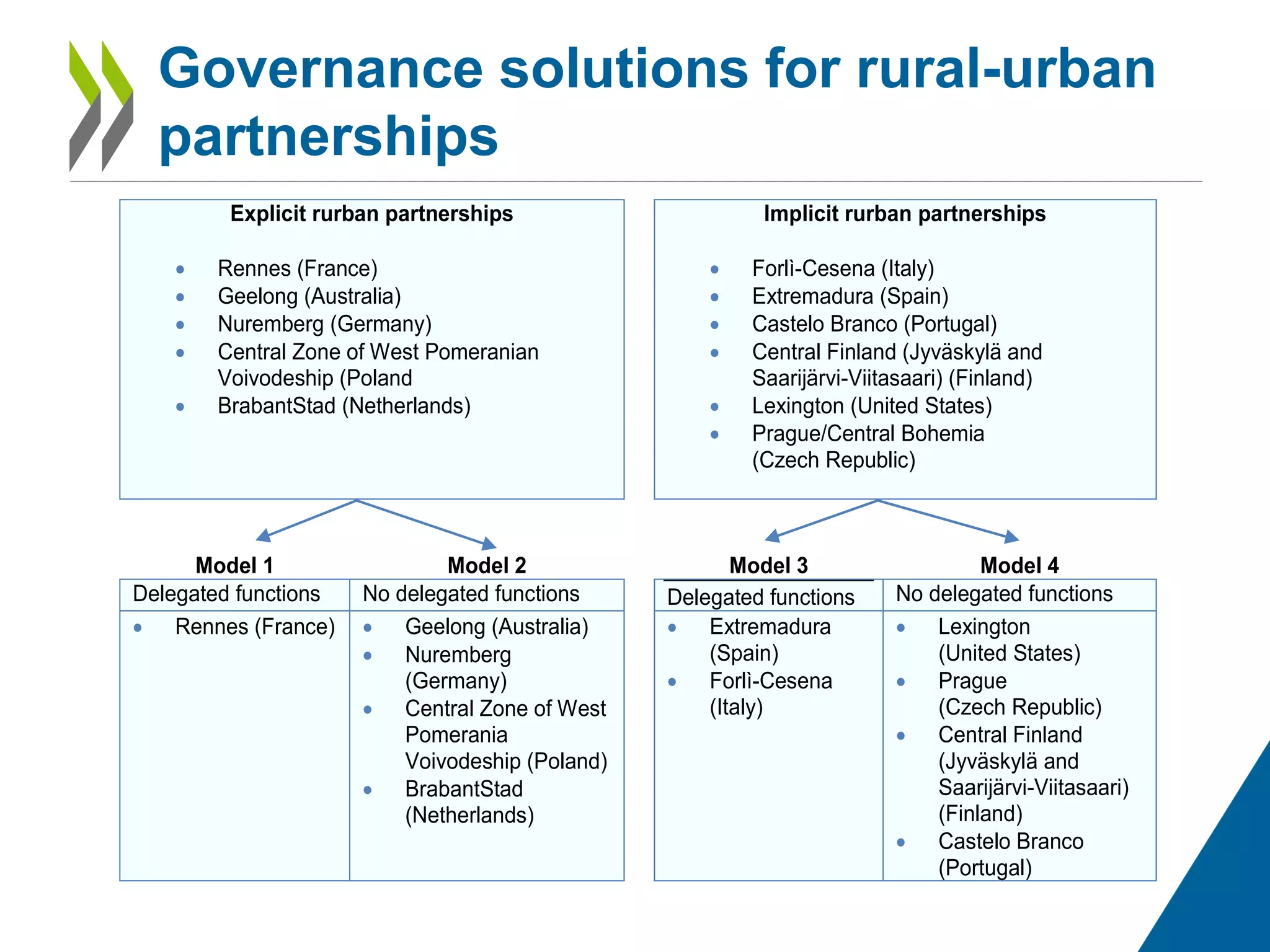

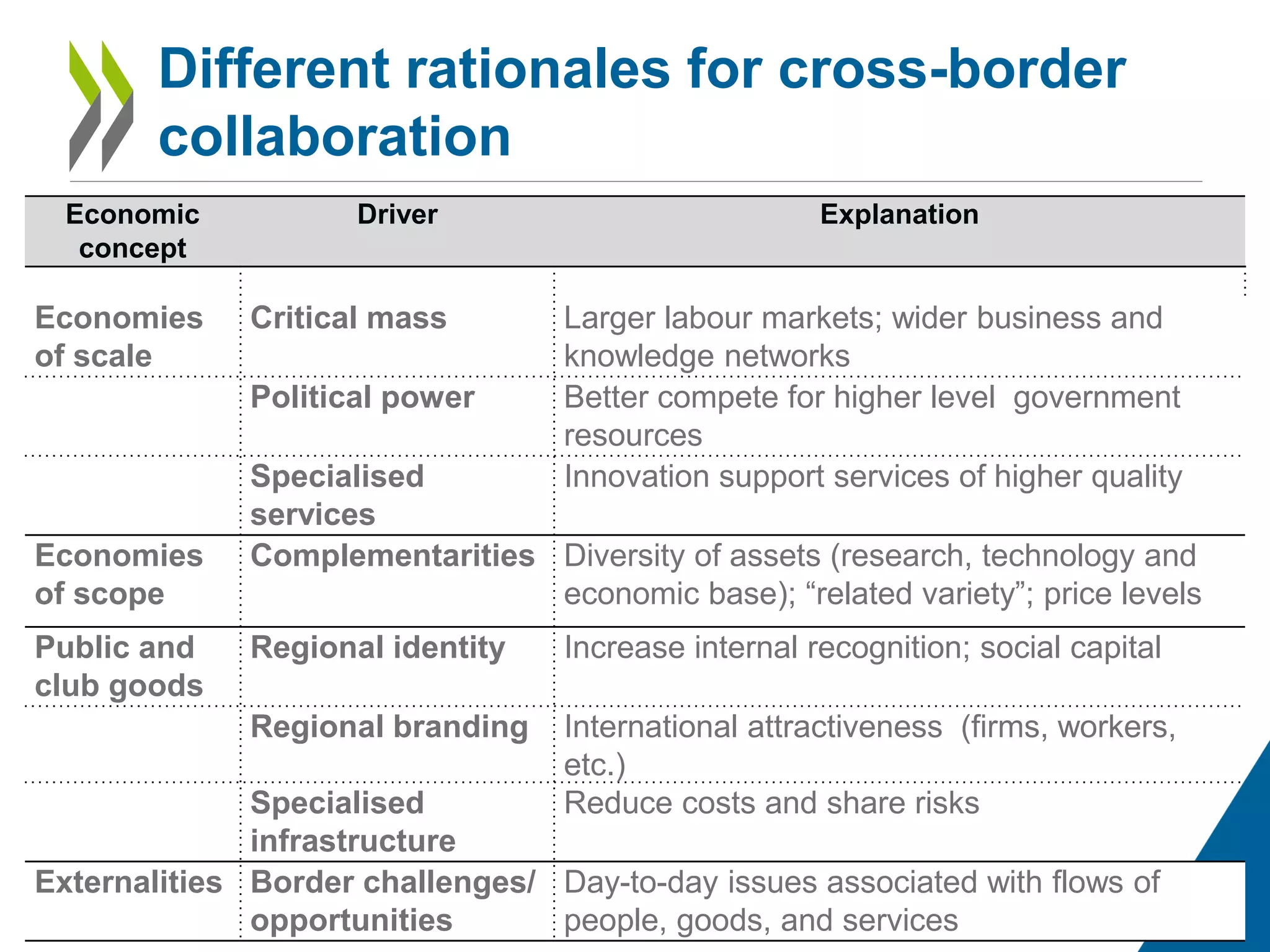

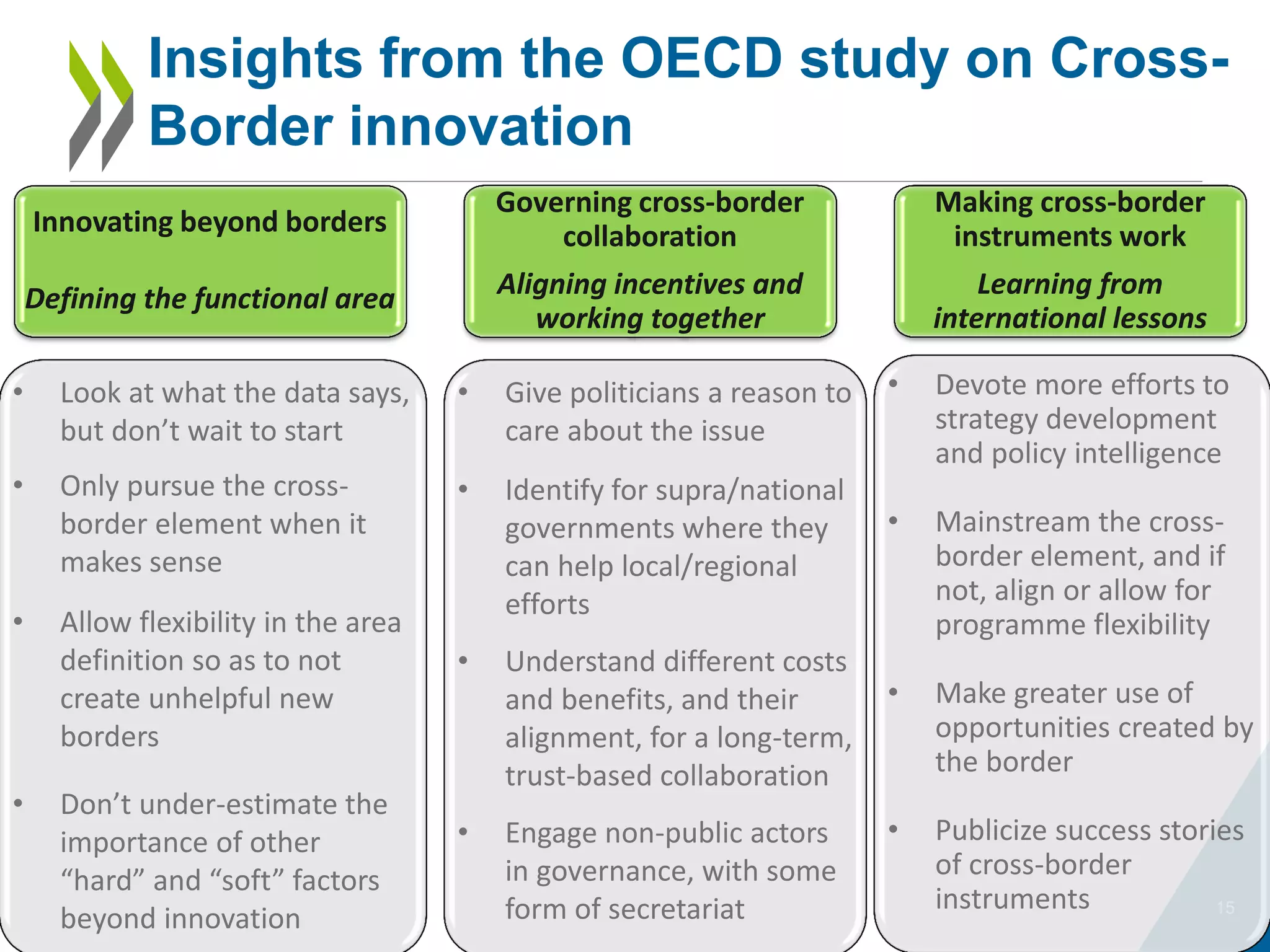

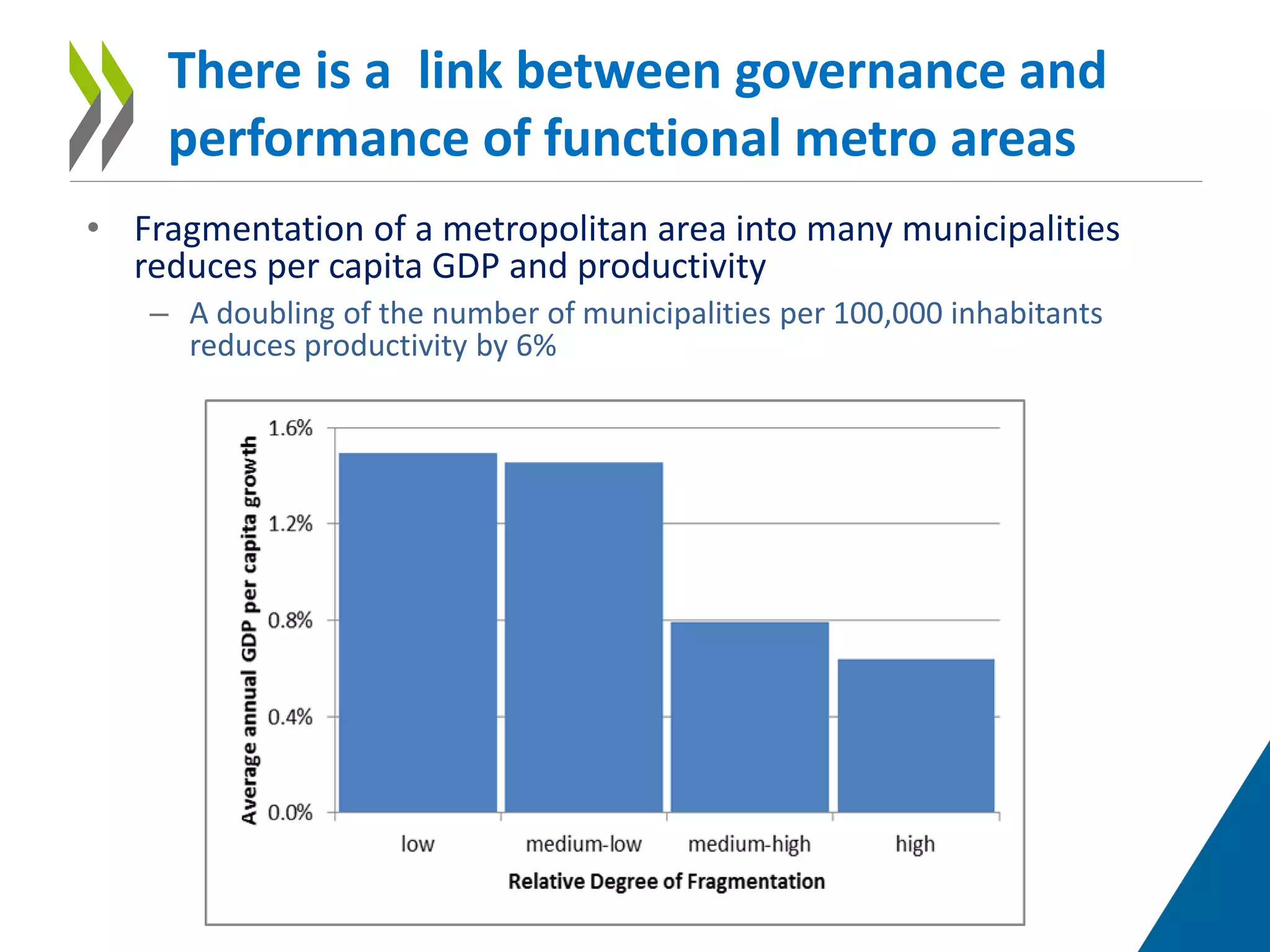

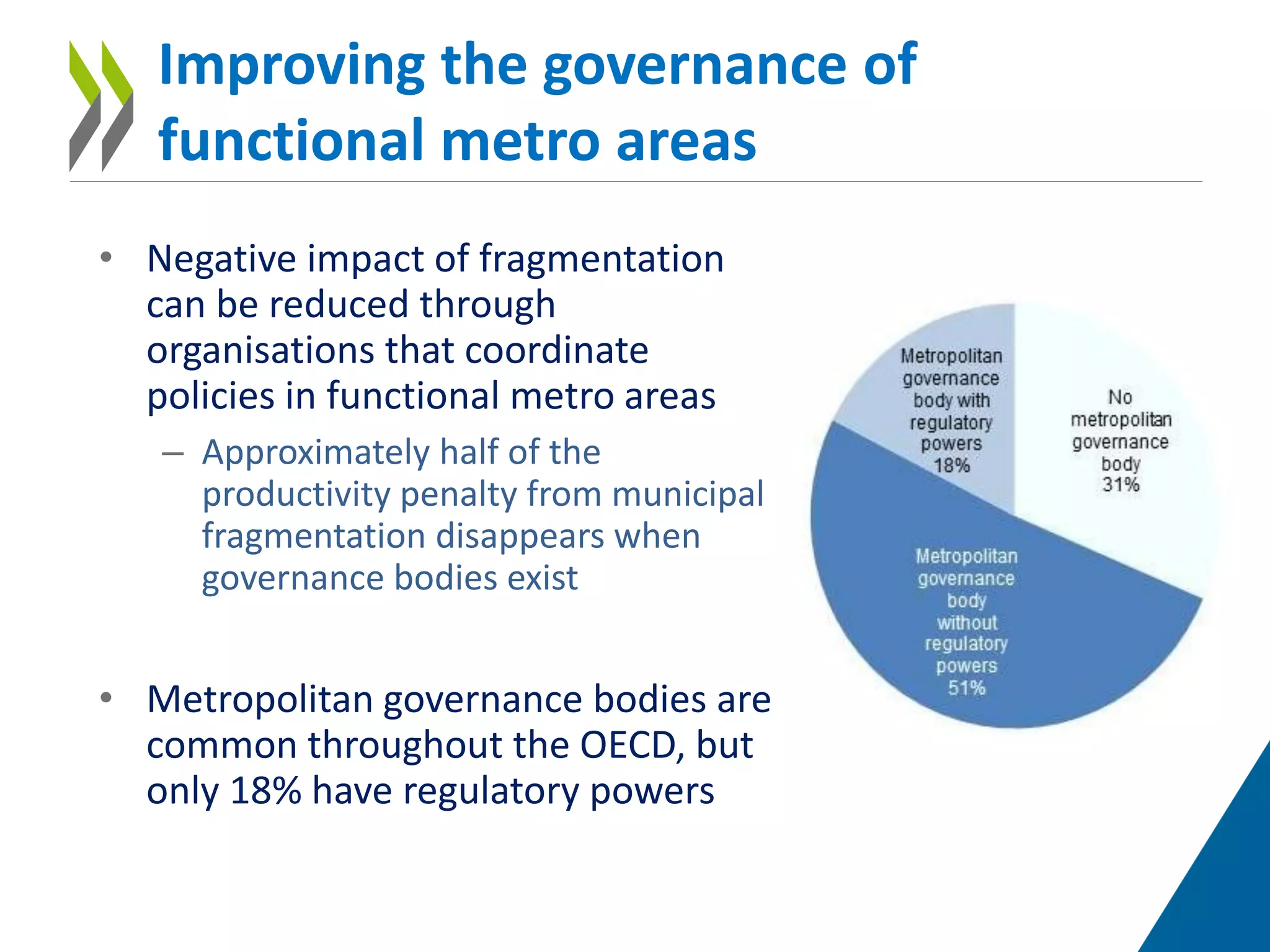

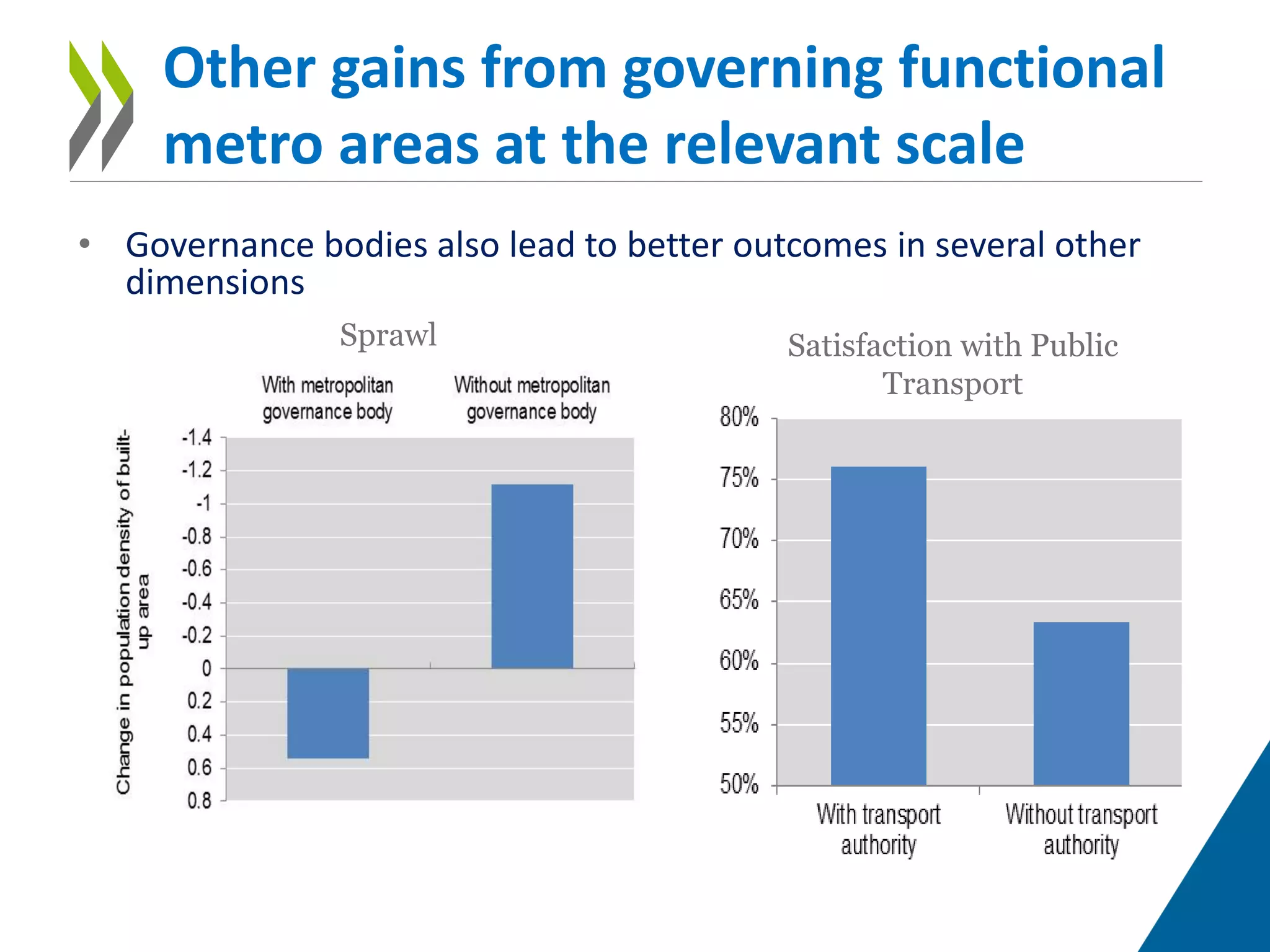

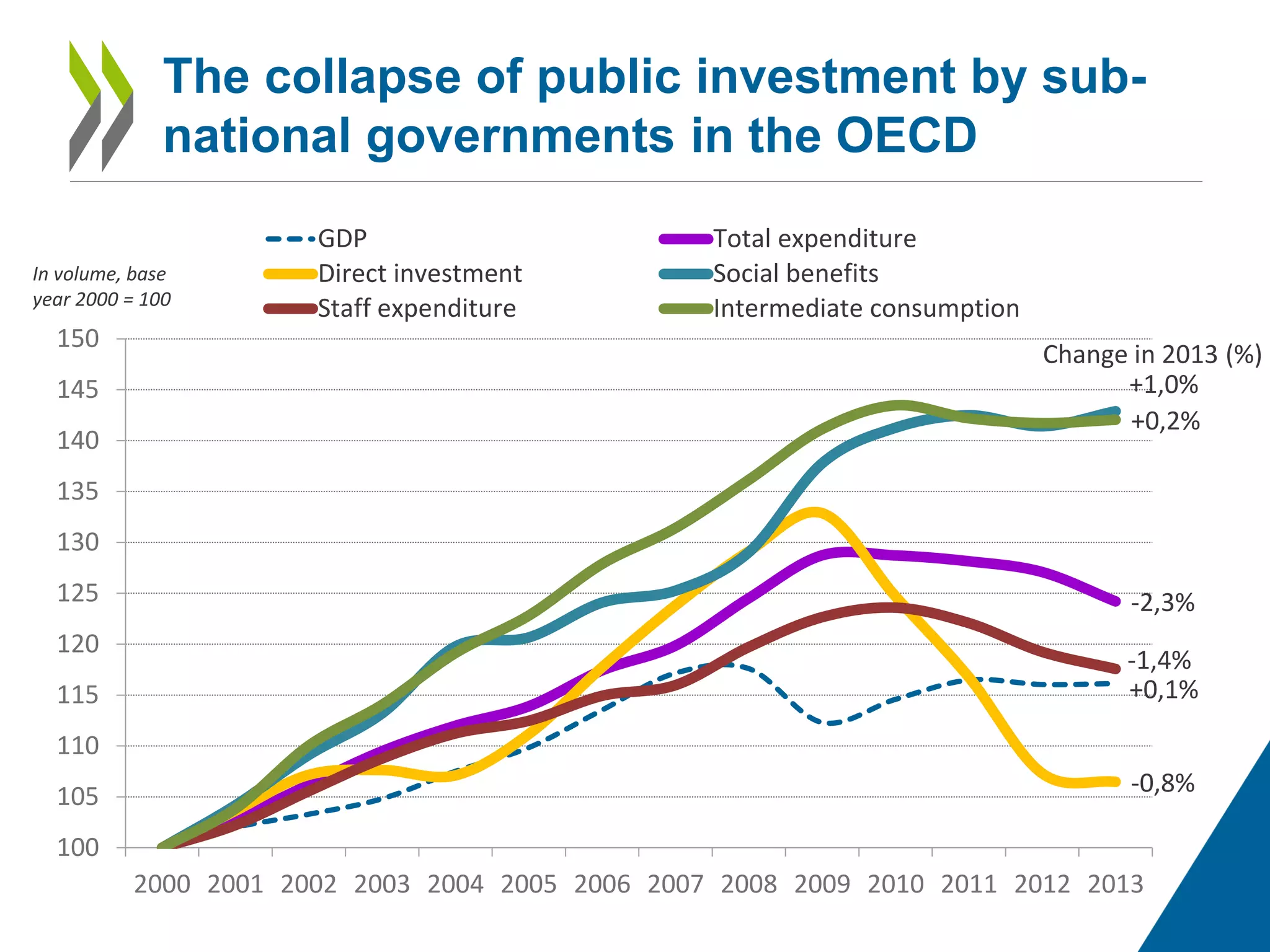

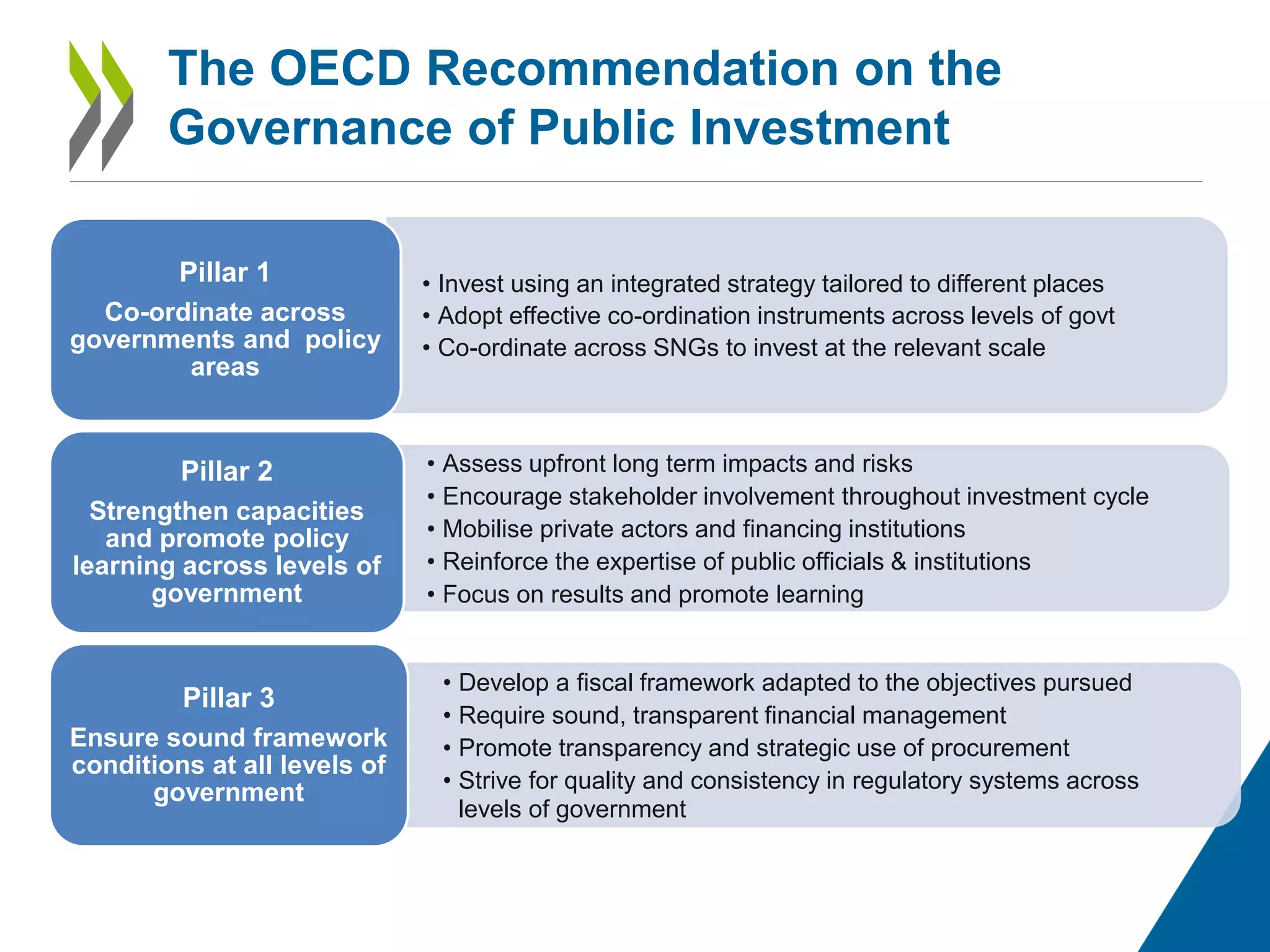

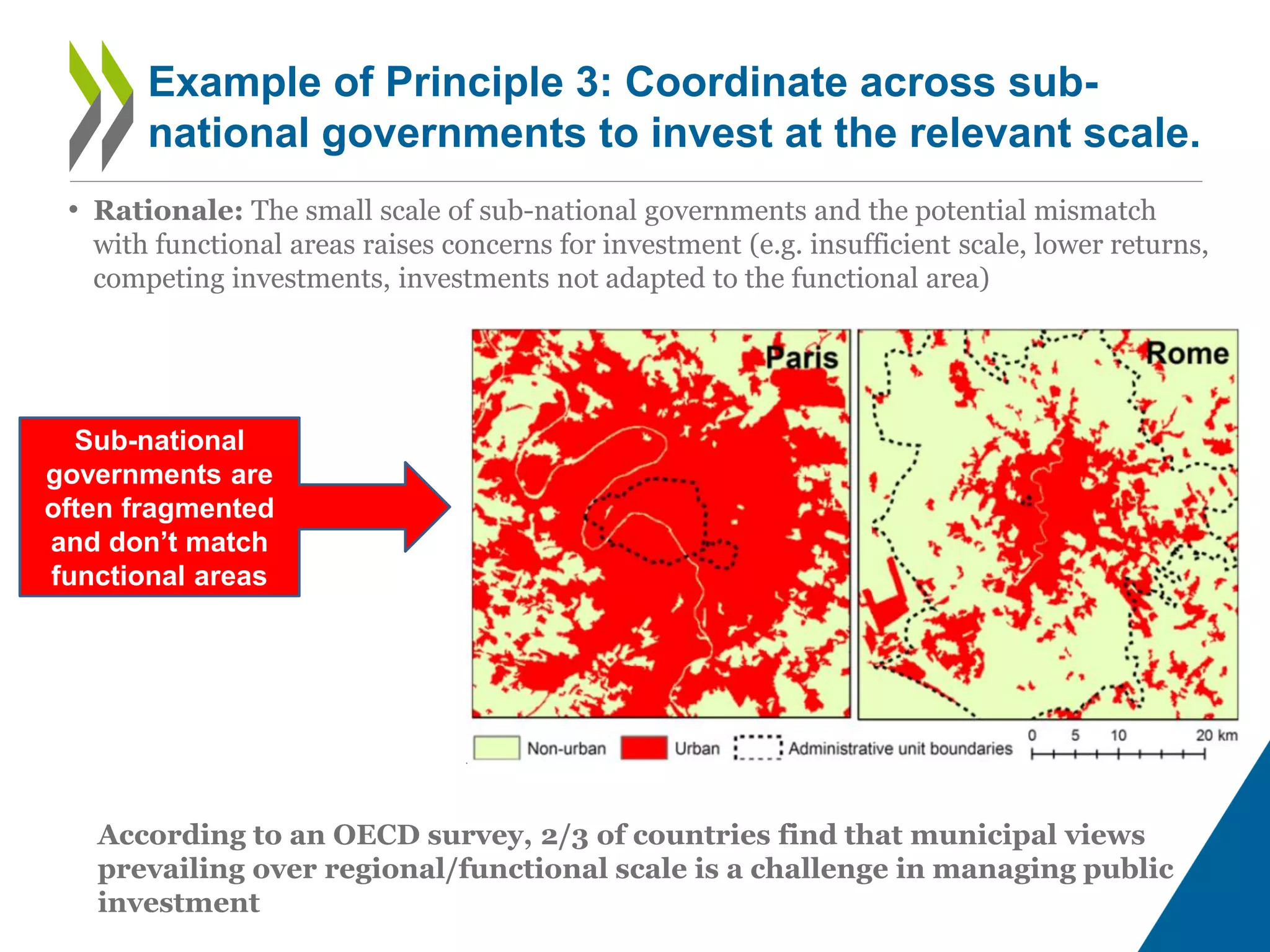

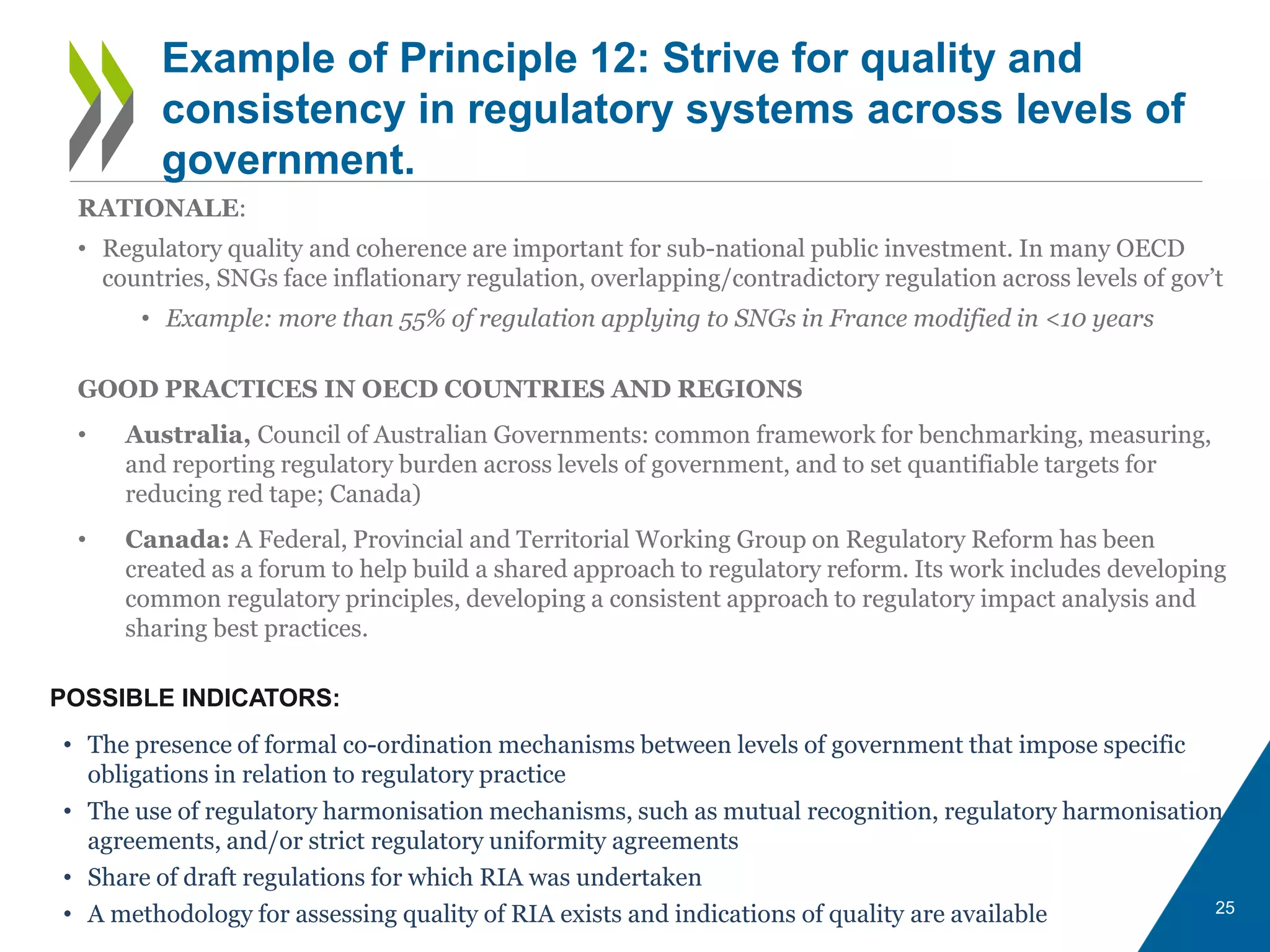

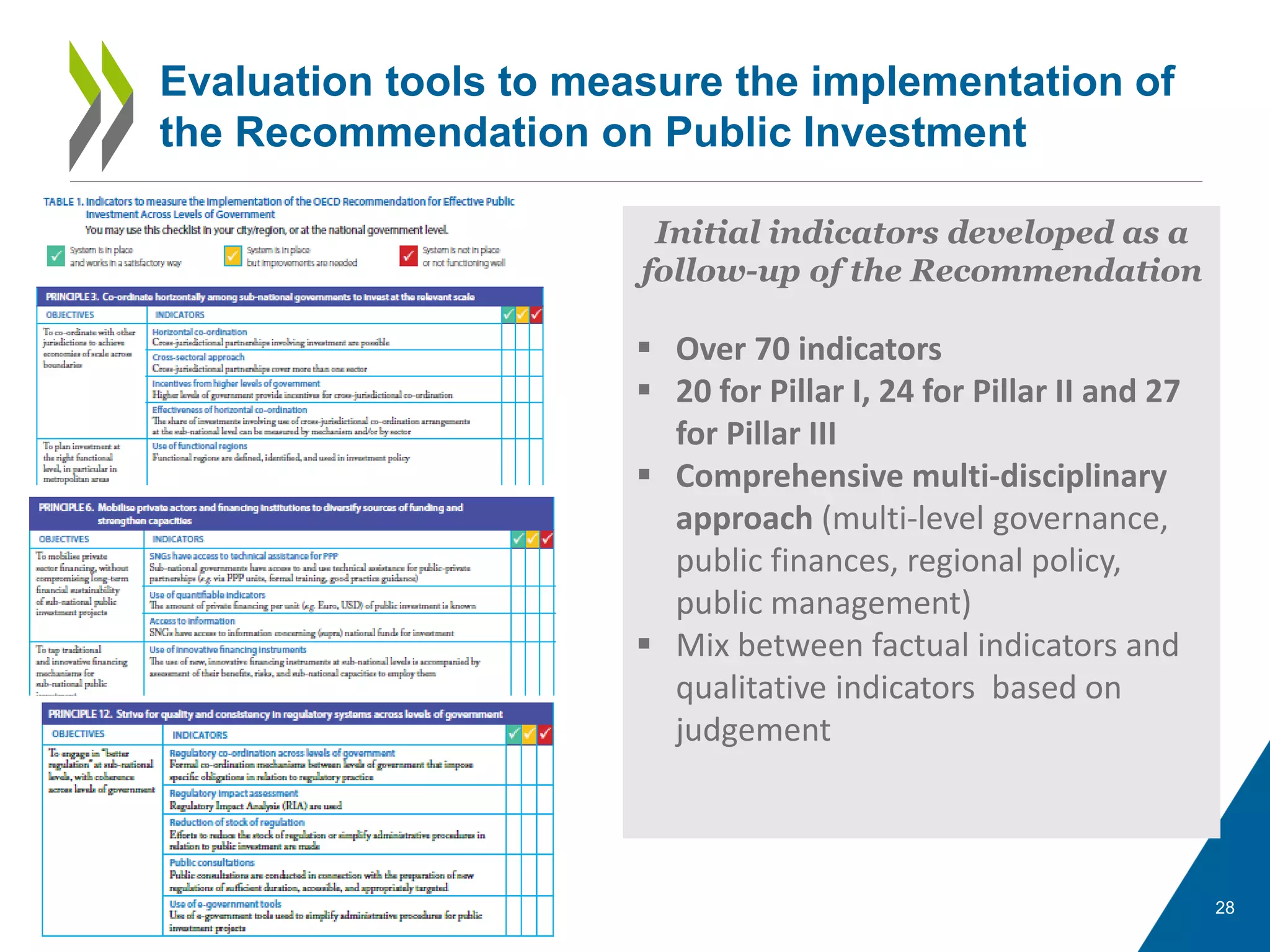

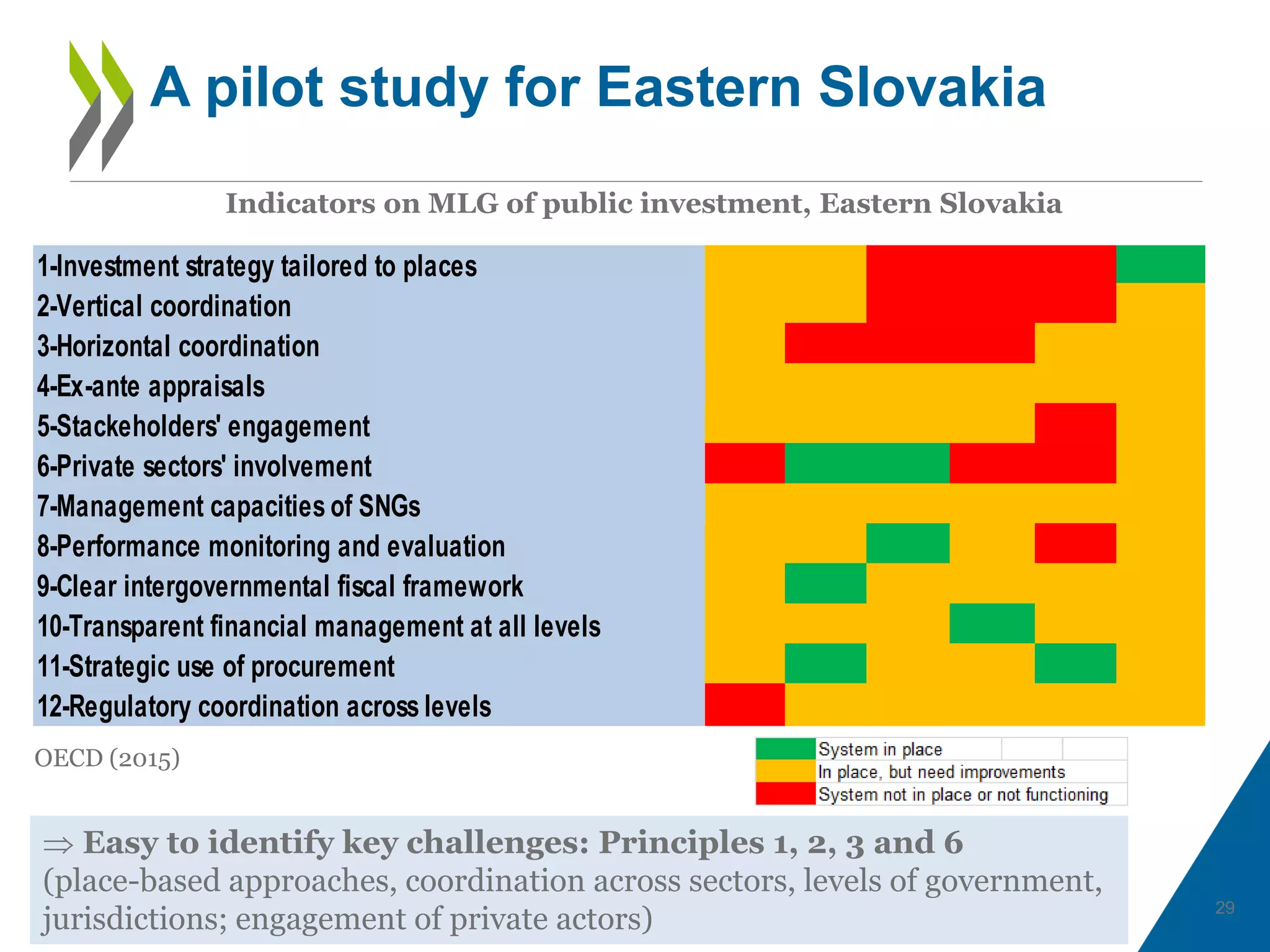

The document discusses the importance of effective multi-level governance in regional policies, identifying gaps in coordination among various governmental levels and proposing specific governance solutions to address these challenges. It highlights the need for strategic planning, capacity building, funding mechanisms, and improved accountability to enhance the effectiveness of public investment and urban-rural partnerships. Additionally, it emphasizes the benefits of collaborative frameworks in boosting productivity and public service quality across fragmented metropolitan areas.