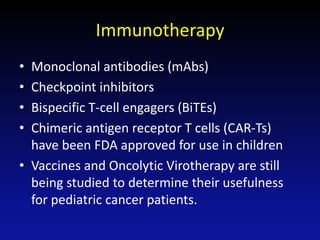

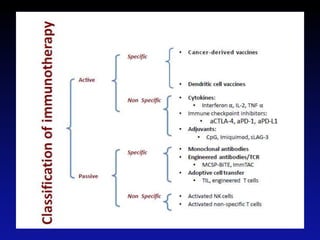

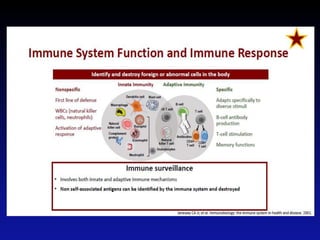

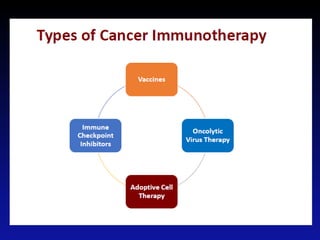

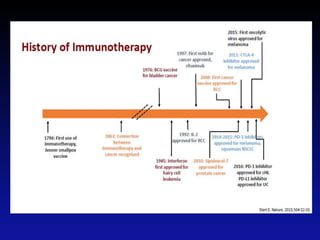

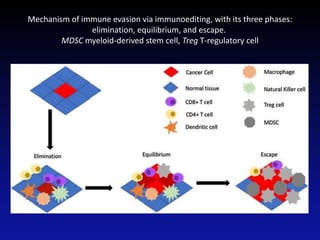

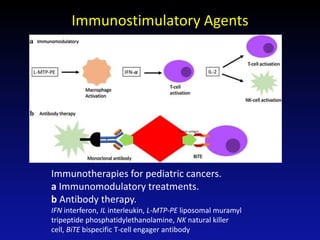

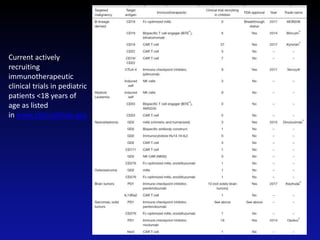

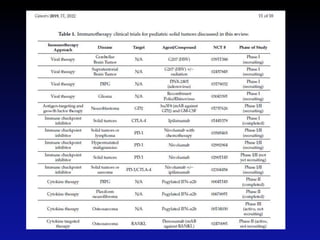

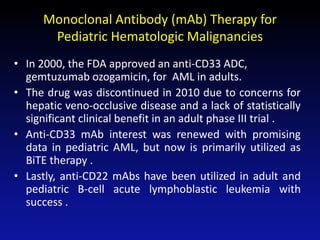

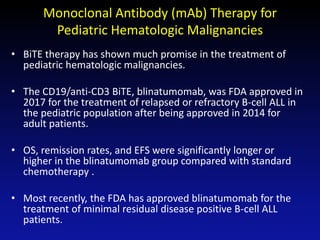

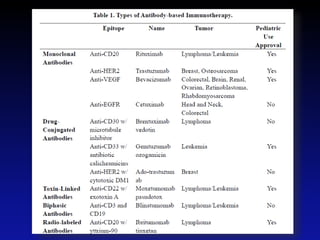

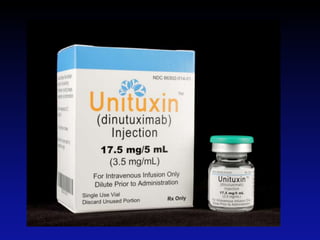

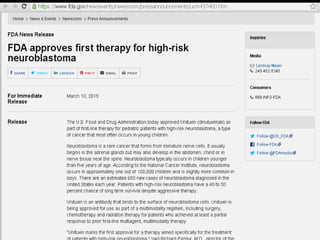

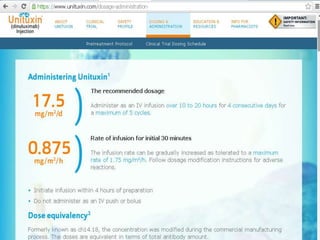

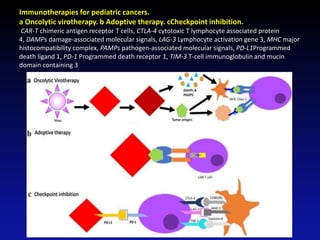

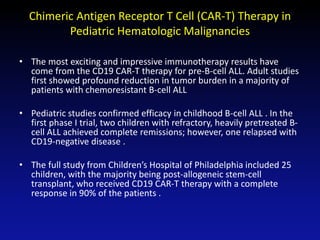

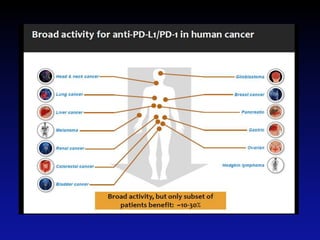

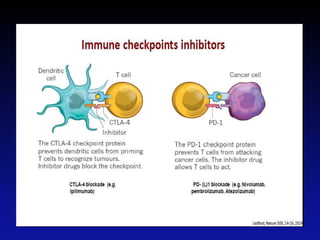

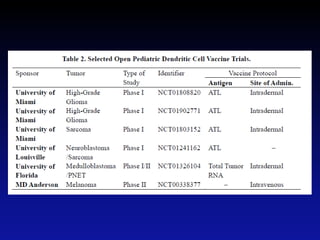

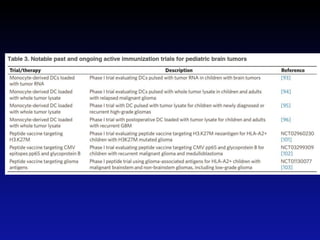

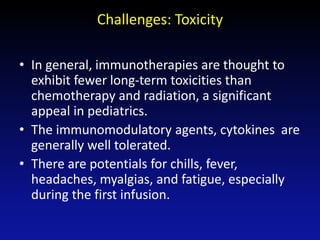

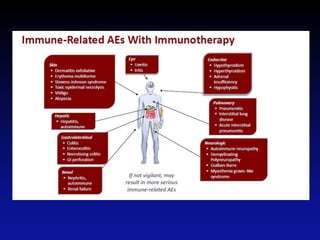

Immunotherapy is emerging as a promising treatment option for pediatric malignancies, with various FDA-approved therapies like monoclonal antibodies and CAR-T cells showing significant potential. Despite challenges such as the need for predictive biomarkers and the effects of the tumor microenvironment, research continues to explore and advance these therapies to improve survival rates among children with cancer. Overall, immunotherapy represents a shift away from traditional treatments, potentially offering better outcomes and reduced long-term side effects.