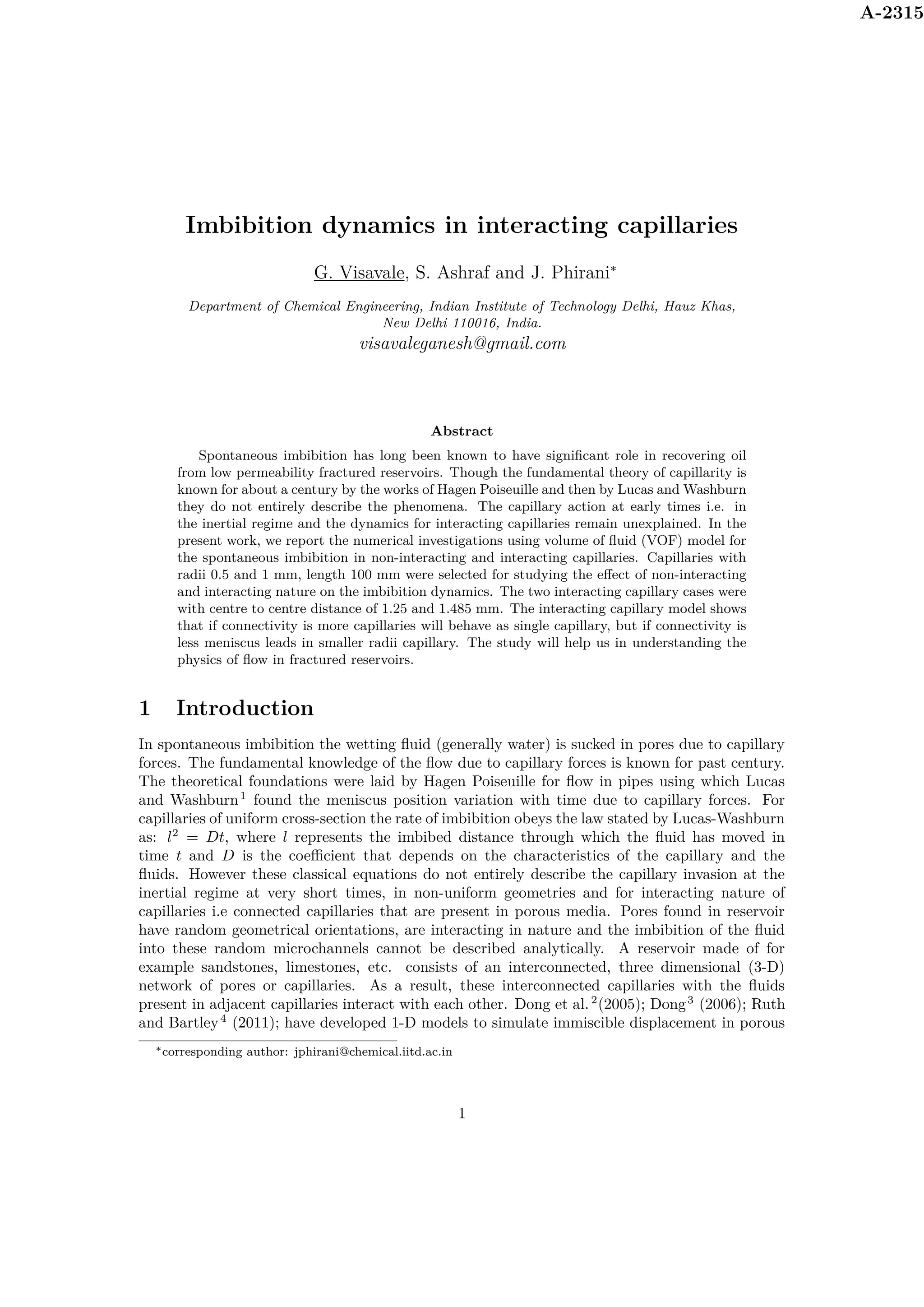

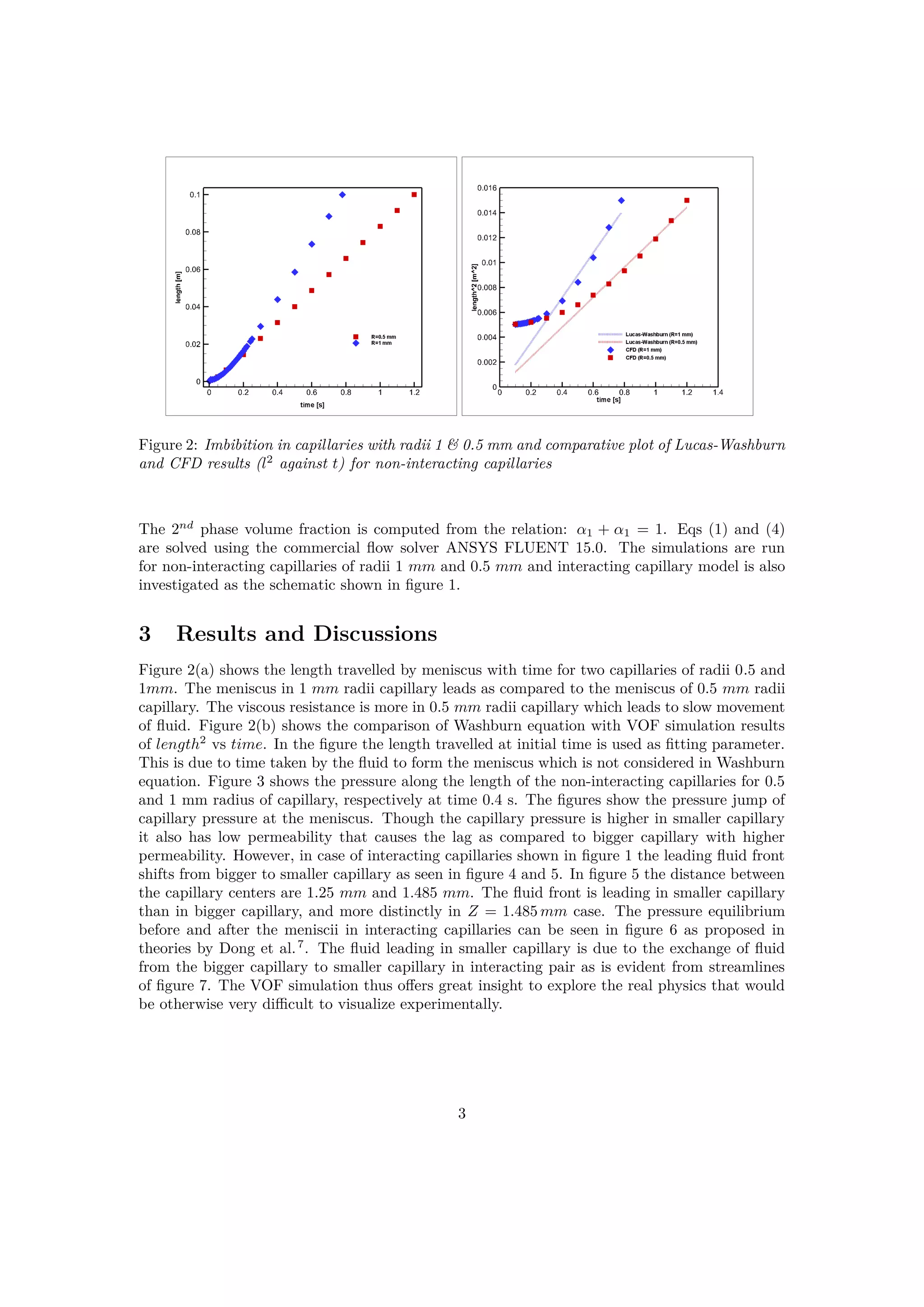

This study investigates spontaneous imbibition dynamics in both non-interacting and interacting capillaries using a volume of fluid model. It reveals that while traditional models like the Washburn equation fail to explain early-time meniscus formation in non-interacting capillaries, the behavior of interacting capillaries is heavily influenced by connectivity, allowing them to behave like a single capillary when more connected. The findings enhance the understanding of fluid flow in fractured reservoirs, providing valuable insights into capillary action in porous media.

![Figure 1: Schematic of interacting and non-interacting capillaries, Z is the centre to centre

distance between capillaries of radii 1 and 0.5 mm

media. However their work also do not consider the entry effects (inertial regime) and the degree

of connectivity between the interacting capillaries.

In the present work, we report the numerical investigations of the spontaneous imbibition

in non-interacting and interacting capillaries and investigate the effect of degree of connectivity

on the imbibition pattern. These results will help us in understanding the physics of flow in

fractured reservoirs.

2 Computational model

In this study, the volume of fluid (VOF) method (Hirt and Nichols5

, 1981) was used to simulate

the spontaneous imbibition of a wetting fluid of µ = 0.001 kg/ms, ρ=998 kg/m3

, in a capillary

filled with a non-wetting fluid of identical viscosity. The interfacial tension between the fluids

is considered to be 0.072N/m. The fluid phases are considered incompressible and the flow

is assumed to be Newtonian and laminar. In VOF method, the phases are identified by their

volume fraction (αi, i = 1, 2) in a computational cell6

. When αi = 1; the cell is filled with 1st

phase and when αi = 0 cell is filled with the 2nd

phase and if 0 < αi < 1; the cell contains the

interface between the 1st

and 2nd

phases. A single set of Navier-Stokes equation is solved for the

incompressible Newtonian flow:

∂

∂t

(ρv) + · (ρvv) = −δp + [µ( v + ( v)T

)] + ρg + F (1)

where F is the surface tension force per unit volume. When a computational cell is not entirely

occupied by one phase, mixture properties described as:

ρ = α1ρ1 + (1 − α1)ρ2 (2)

µ = α1µ1 + (1 − α1)µ2 (3)

For the qth

phase, advection equation is written as:

∂

∂t

(α1ρ1) + · (α1ρ1v1) = 0 (4)

2](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/a-2315-170922113029/75/Imbibition-dynamics-in-interacting-capillaries-2-2048.jpg)

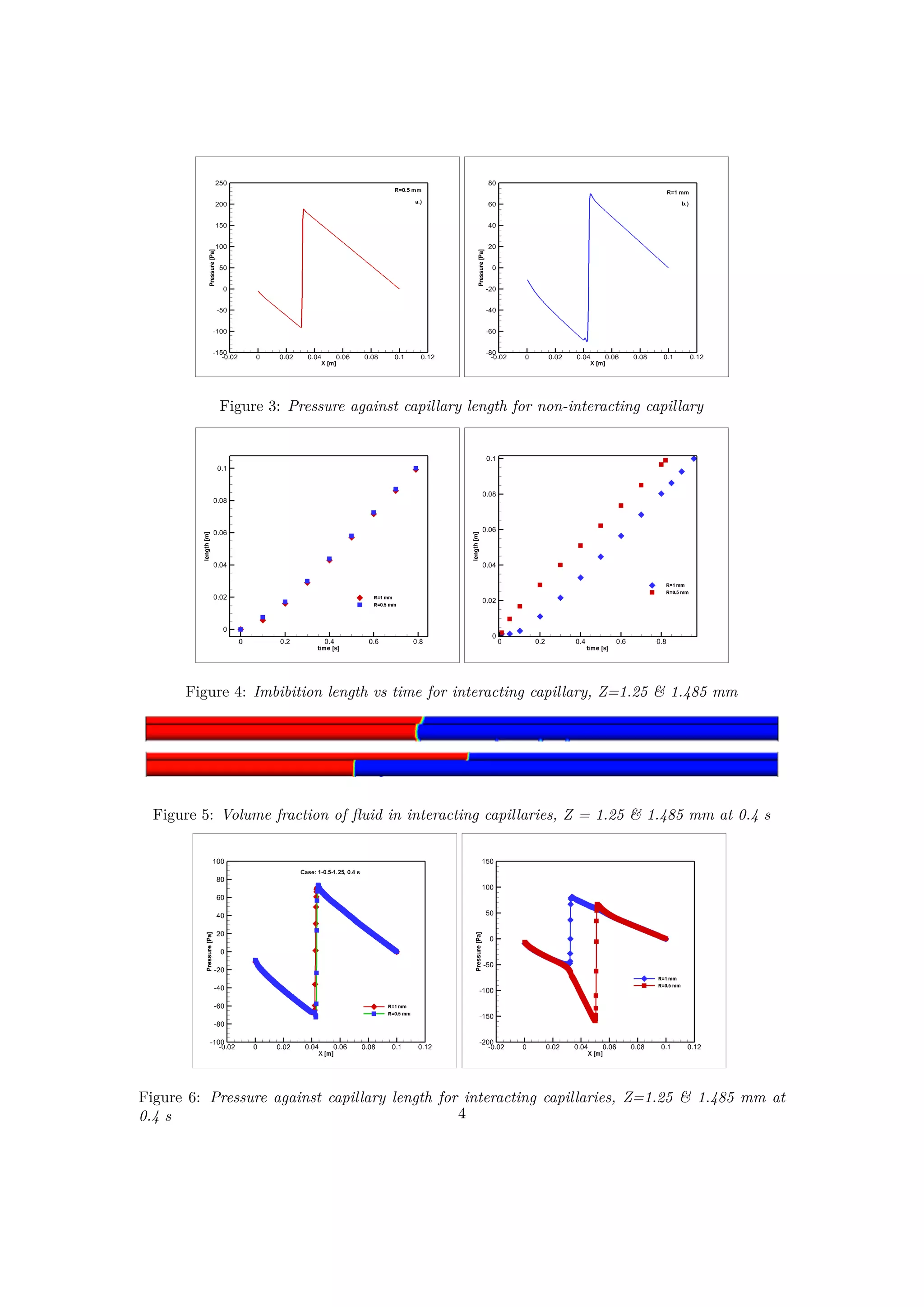

![Figure 7: Streamlines near meniscii region showing transfer of fluid from R=1 mm to R=0.5

mm for cases Z=1.25 and 1.485 mm

4 Conclusions

We successfully investigate the spontaneous imbibition in non-interacting and interacting cap-

illaries with fluids of equal viscosities. In non-interacting capillaries the VOF simulation shows

that Washburn equation is not able to capture the meniscus formation phenomena at early

times. The interacting capillary model shows that if connectivity is more capillaries will behave

as single capillary, but if connectivity is less meniscus leads in smaller radii capillary. VOF

provides insights in analysis of spontaneous imbibition in capillaries enabling good visualization

and tracking of interface (meniscii) between the two fluids.

References

1. Edward W. Washburn. The dynamics of capillary flow. Phys. Rev., Mar 1921.

2. Mingzhe Dong, Francis AL Dullien, Liming Dai, and Daiming Li. Immiscible displacement

in the interacting capillary bundle model part i. development of interacting capillary bundle

model. Transport in Porous media, 59(1):1–18, 2005.

3. Mingzhe Dong, Francis AL Dullien, Liming Dai, and Daiming Li. Immiscible displacement

in the interacting capillary bundle model part ii. applications of model and comparison of

interacting and non-interacting capillary bundle models. Transport in Porous media, 63(2):

289–304, 2006.

4. Douglas Ruth and Jonathan Bartley. Capillary tube models with interaction between the

tubes [a note on “immiscible displacement in the interacting capillary bundle model part i.

development of interacting capillary bundle model”, by dong, m., dullien, fal, dai, l. and li,

d., 2005, transport porous media]. Transport in porous media, 86(2):479–482, 2011.

5. Cyril W Hirt and Billy D Nichols. Volume of fluid (vof) method for the dynamics of free

boundaries. Journal of computational physics, 39(1):201–225, 1981.

6. Ansys Fluent Ansys. 14.0 theory guide. ANSYS Inc, 2011.

7. Mingzhe Dong, Jun Zhou, et al. Characterization of waterflood saturation profile histories by

the ‘complete’capillary number. Transport in porous media, 31(2):213–237, 1998.

5](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/a-2315-170922113029/75/Imbibition-dynamics-in-interacting-capillaries-5-2048.jpg)