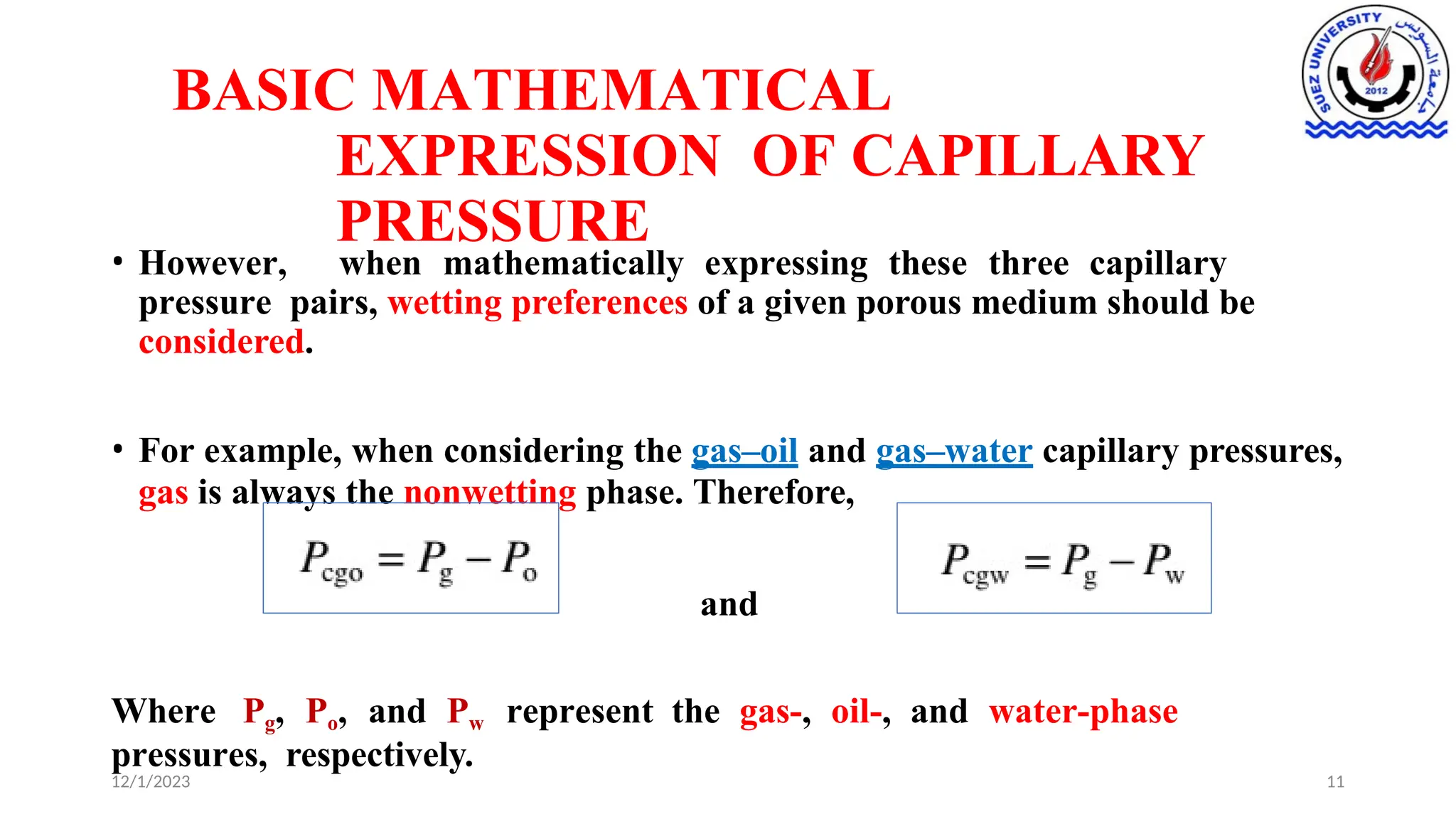

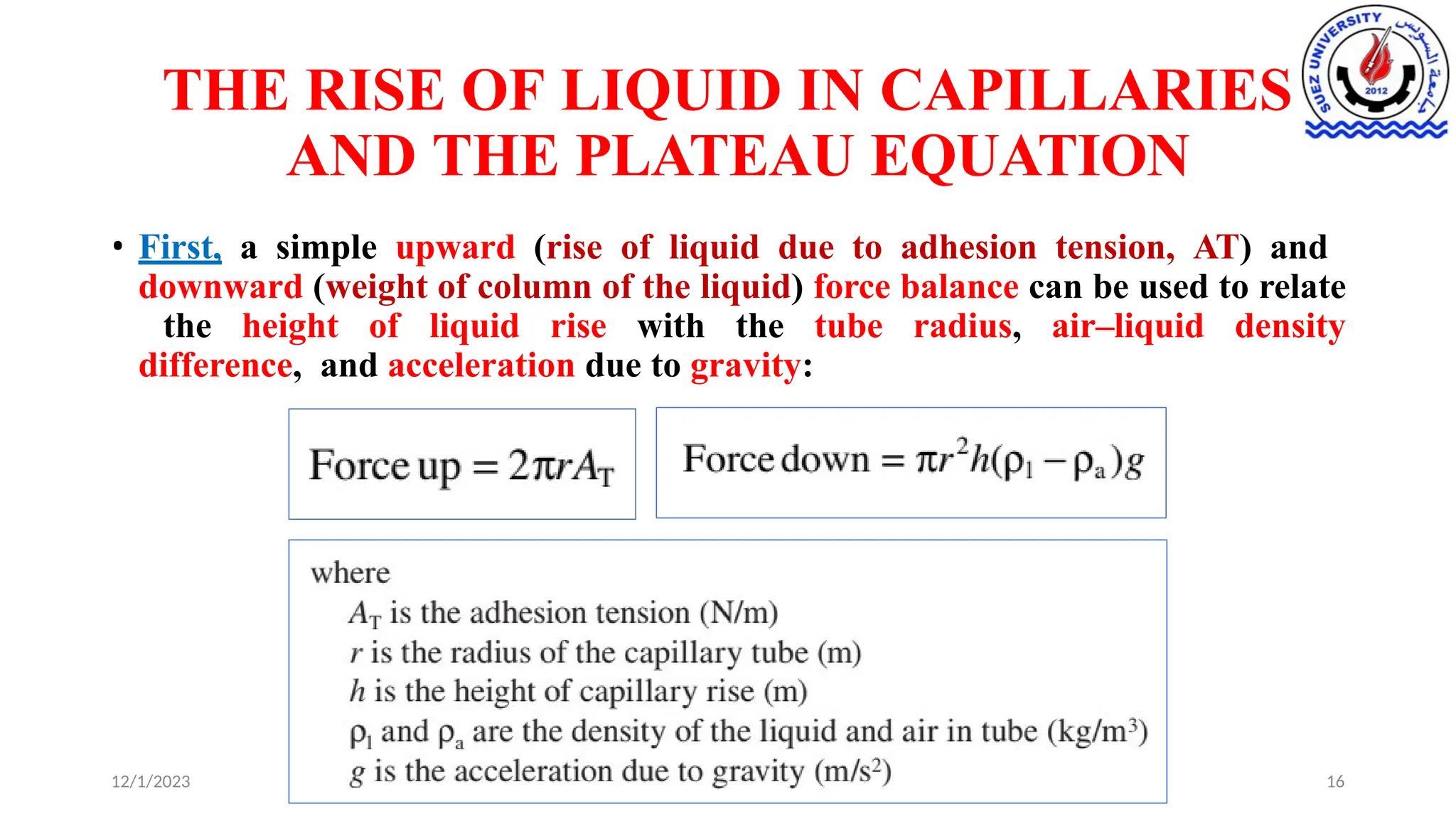

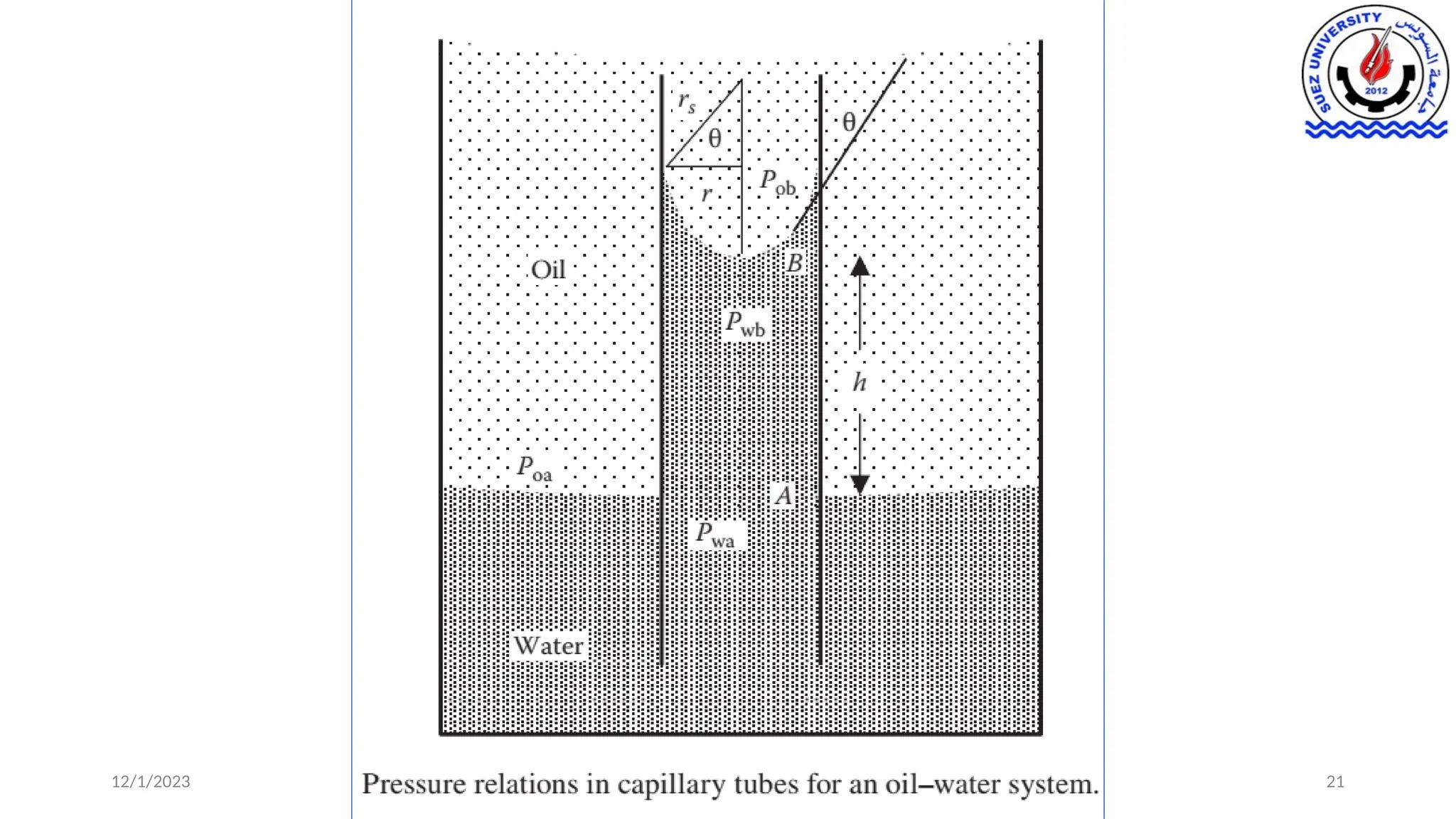

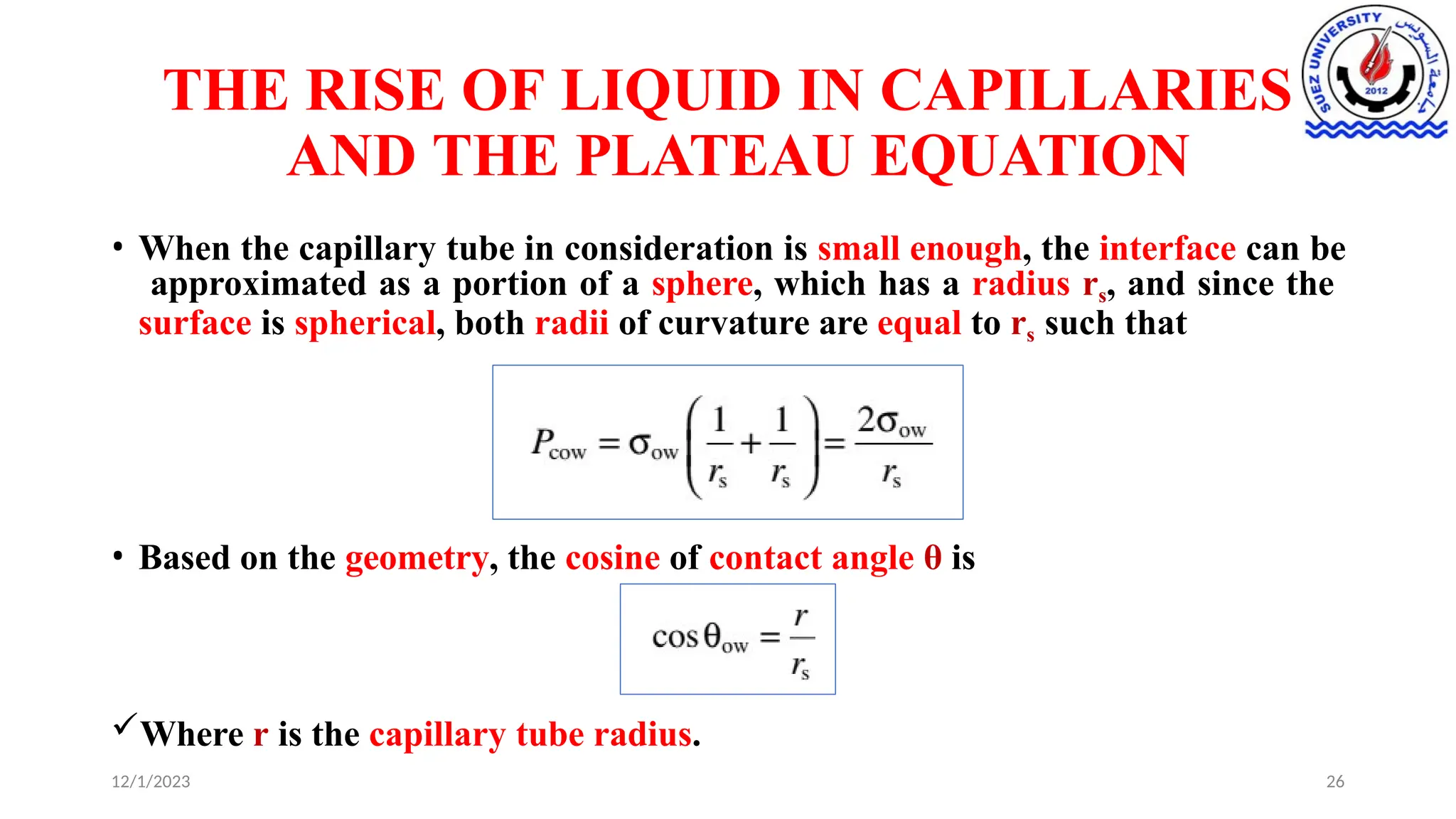

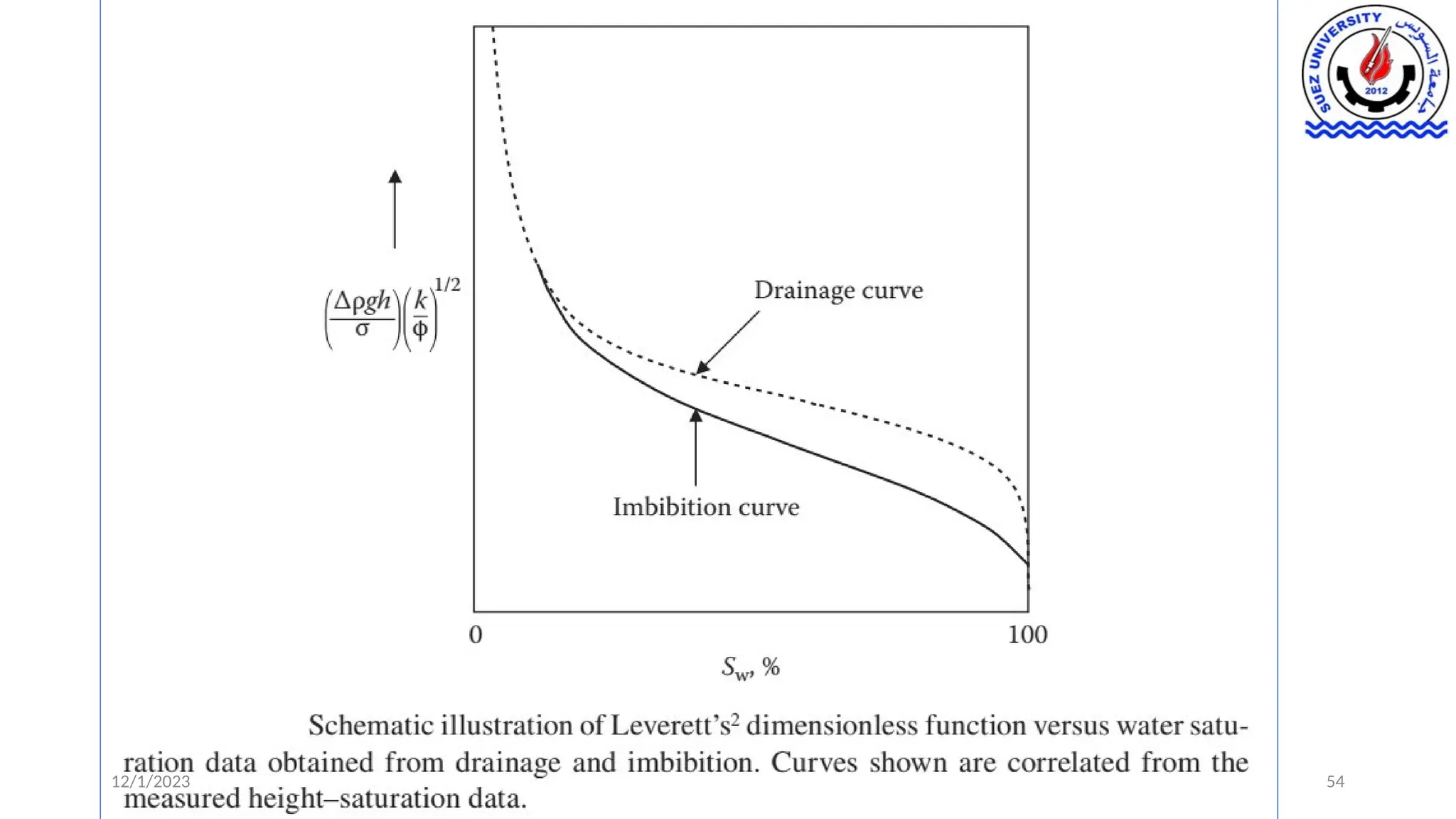

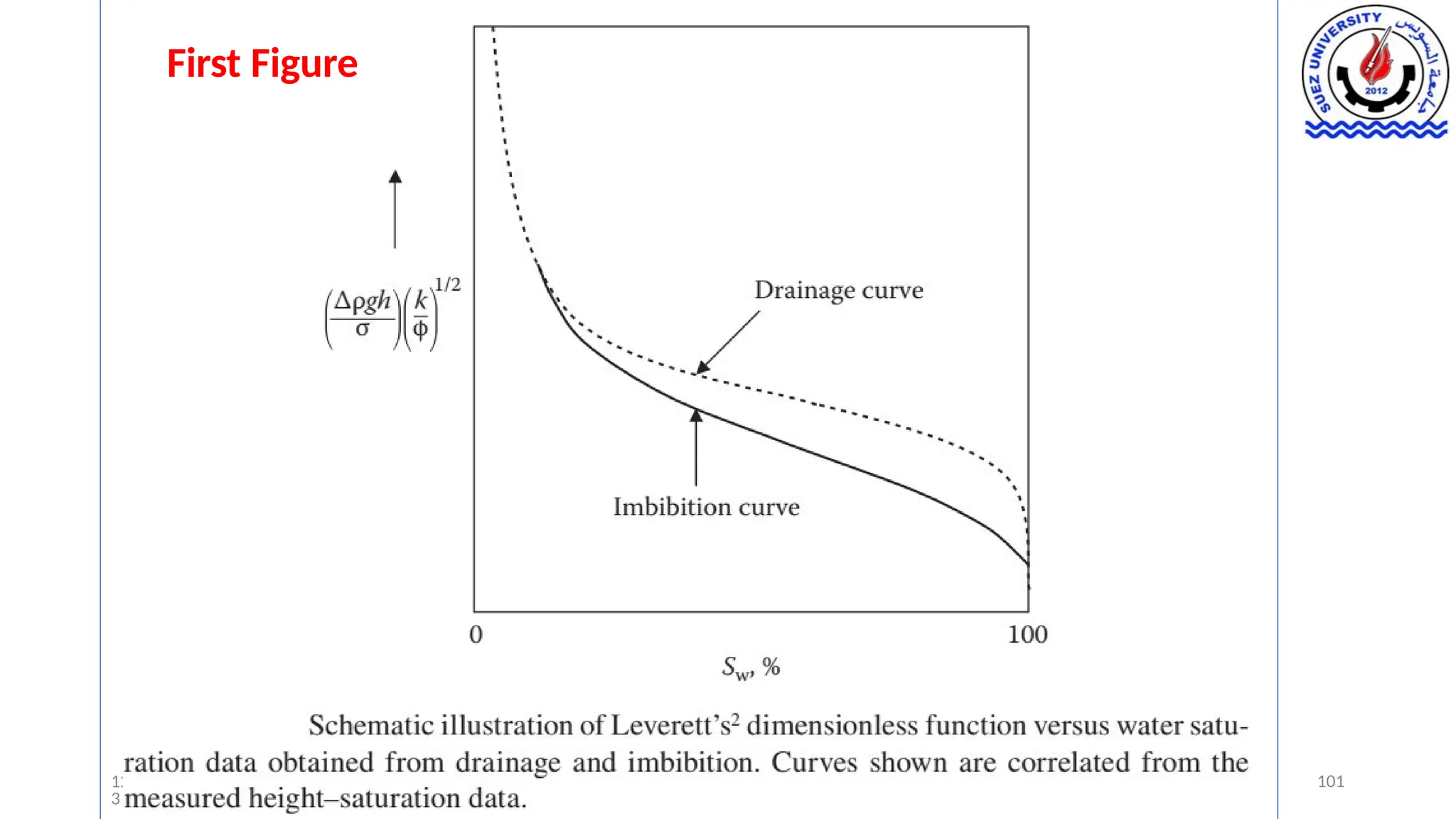

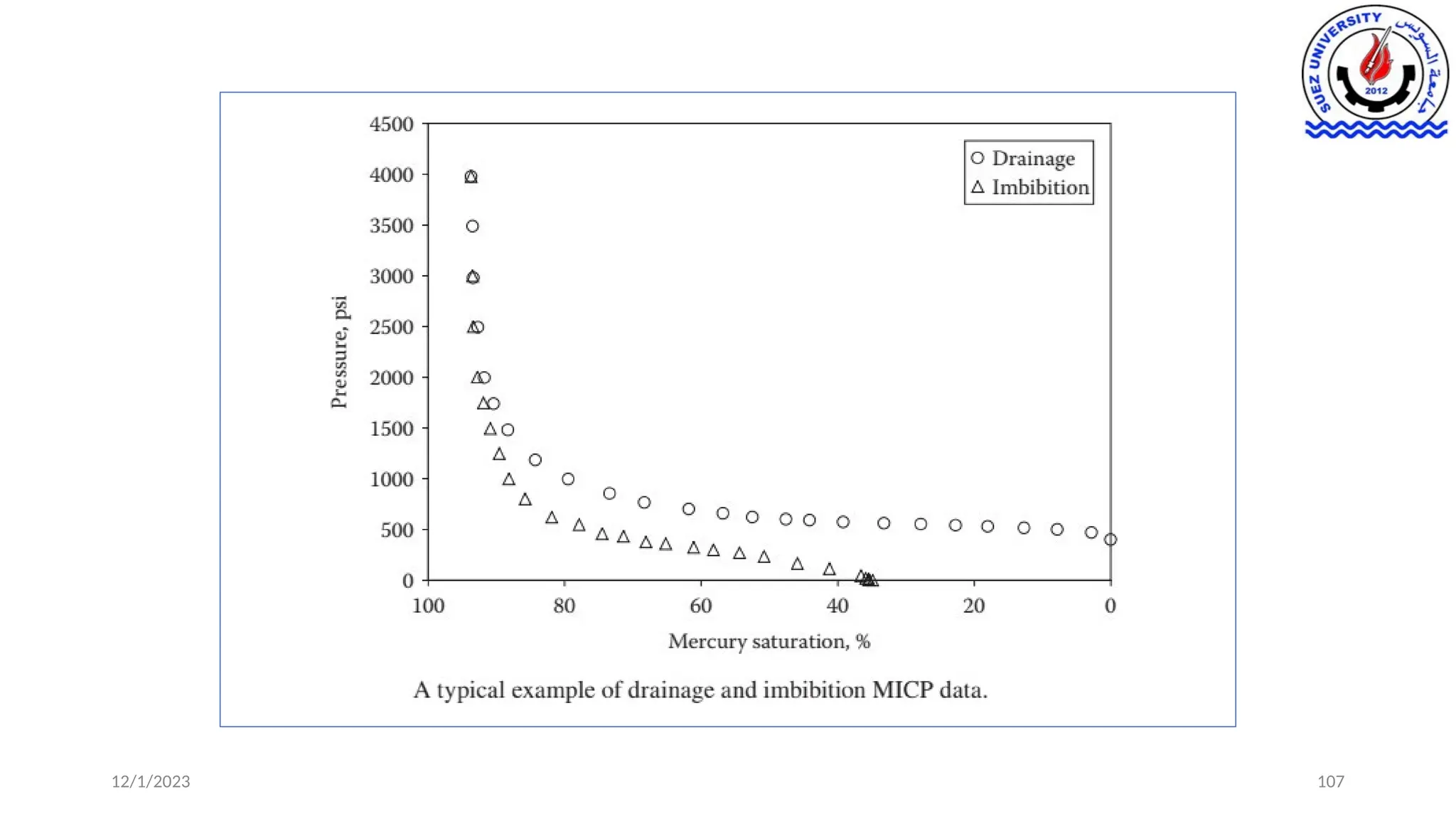

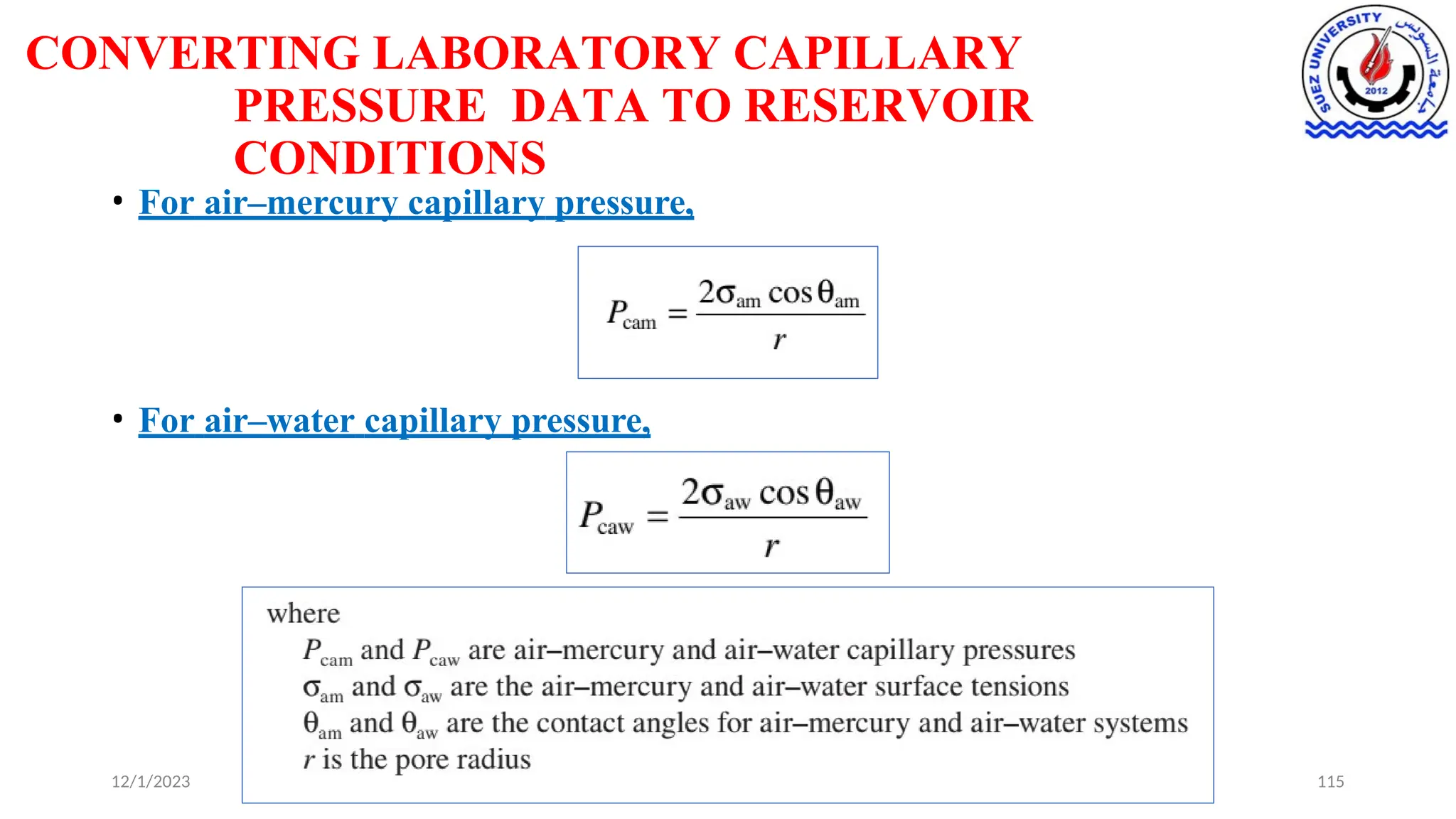

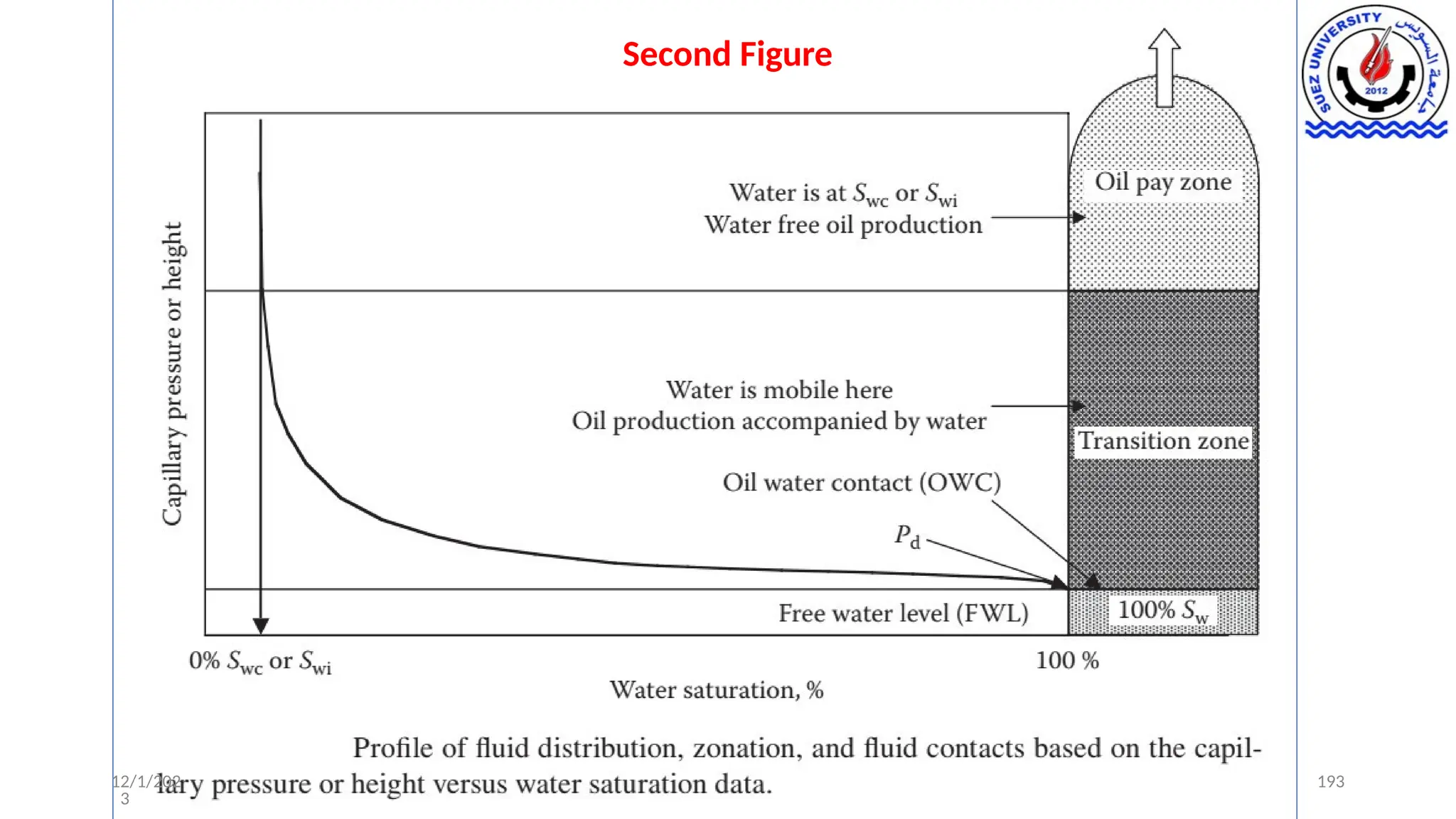

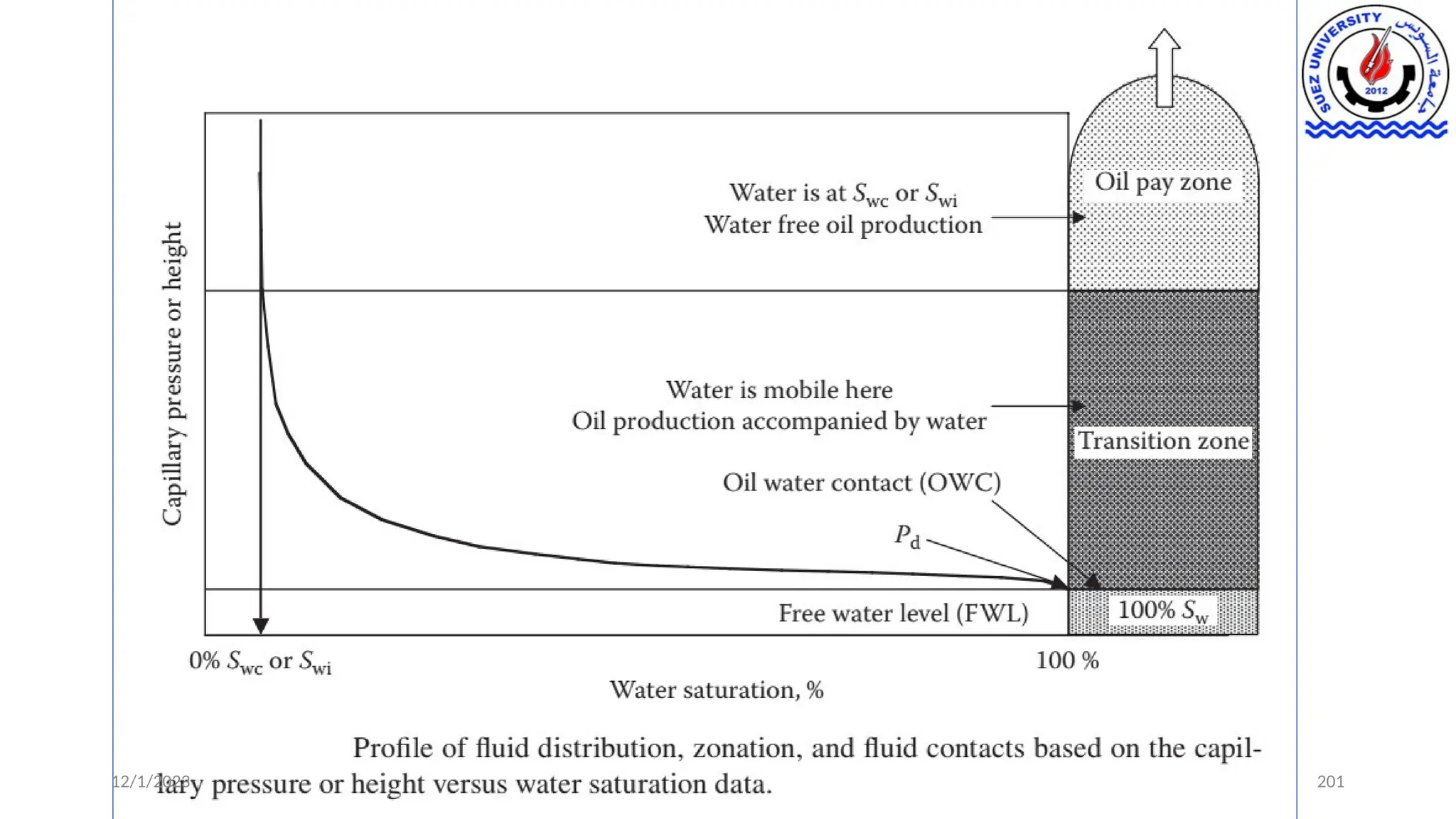

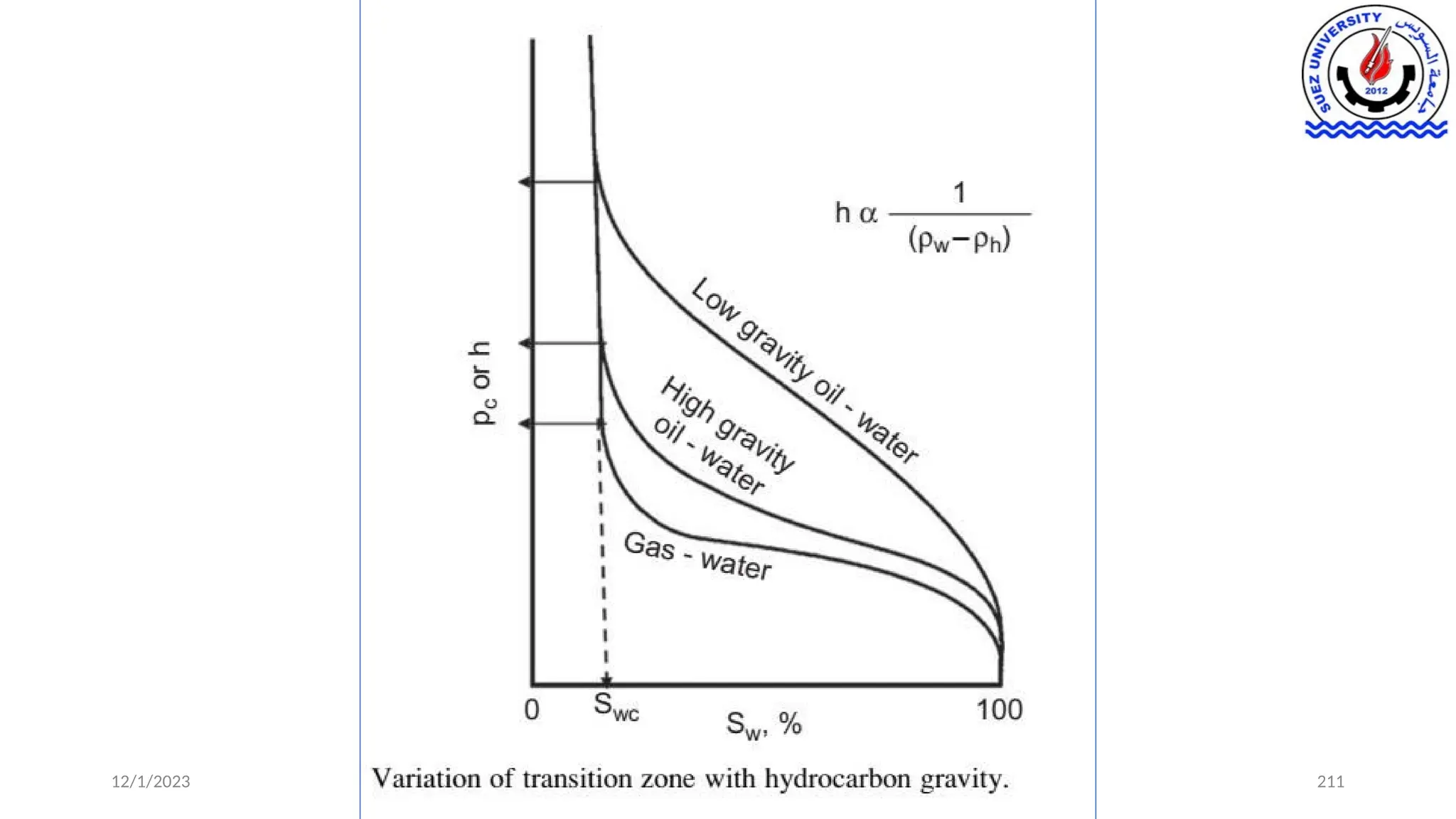

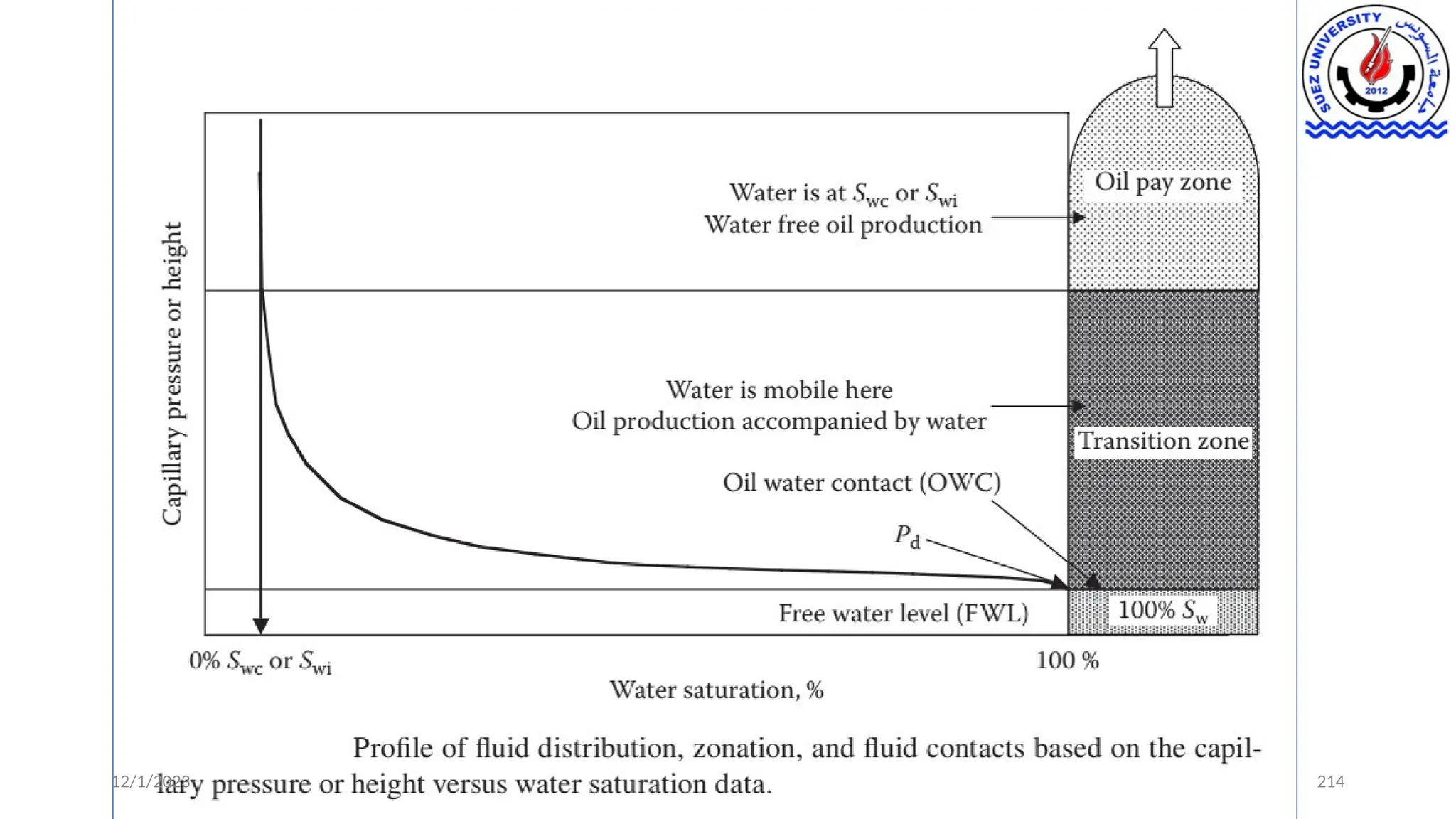

This document discusses capillary pressure in porous media, focusing on its characteristics, measurements, and implications for petroleum reservoirs. It highlights the effects of interfacial tension, wettability, and pore size on capillary forces that govern fluid distribution and hydrocarbon recovery in reservoirs. The document further explores concepts like imbibition and drainage and the relationship between capillary pressure and saturation history.

![INTRODUCTION

12/1/2023 8

• Thus, it is clear from the foregoing that it is advantageous to understand the

nature of these capillary forces both from a static reservoir structure (in

terms of fluid contacts, transition zones, and free water level [FWL]) and the

dynamic actual hydrocarbon recovery standpoint.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/9-241214161748-4209d9c2/75/9-Capillary-Pressure-its-Measurements-and-Applications-pptx-8-2048.jpg)