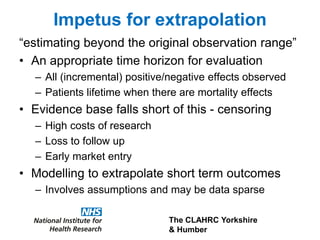

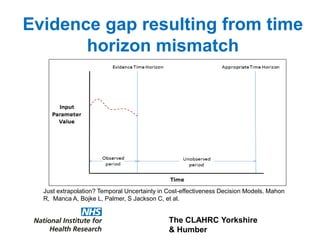

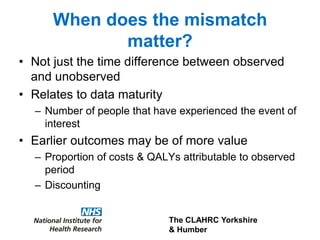

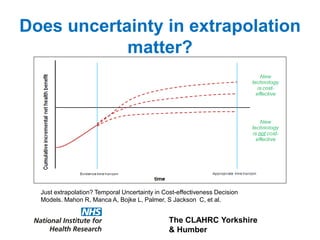

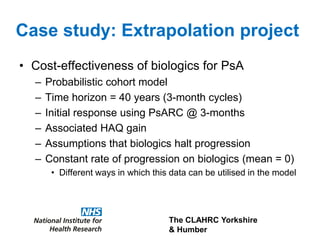

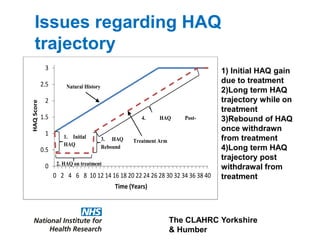

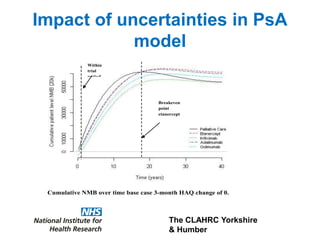

1) The document discusses methods for extrapolating evidence from clinical trials to longer time horizons needed for cost-effectiveness modelling. Extrapolation involves assumptions and uncertainty that must be addressed.

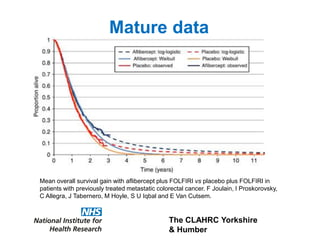

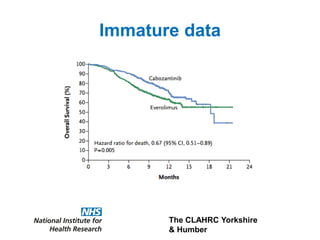

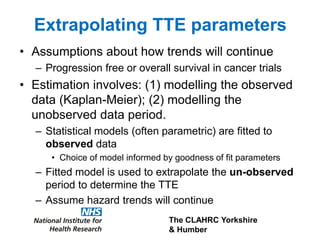

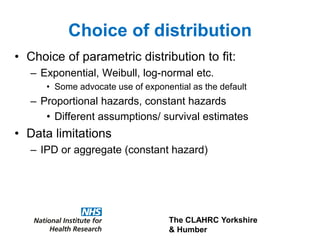

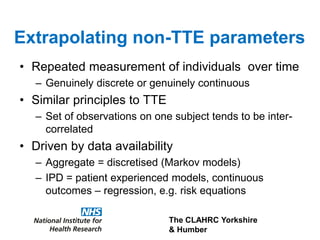

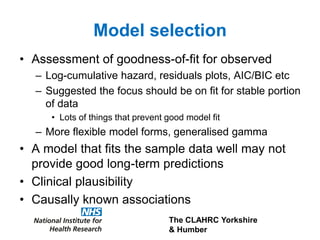

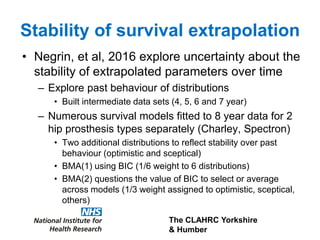

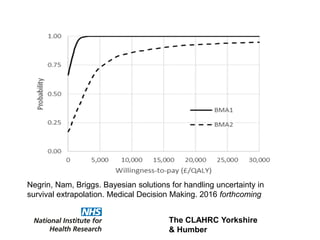

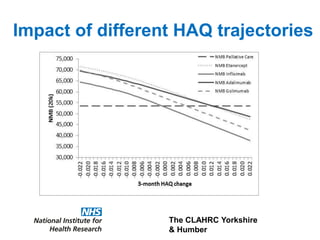

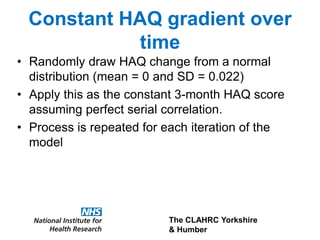

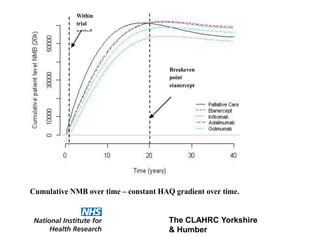

2) Common extrapolation methods include parametric survival models fitted to time-to-event data from trials. Choice of model and assumptions about how trends will continue add uncertainty.

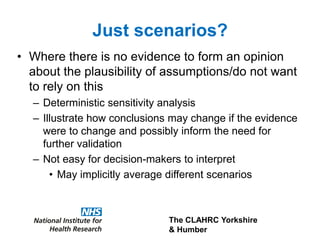

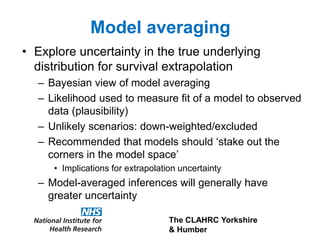

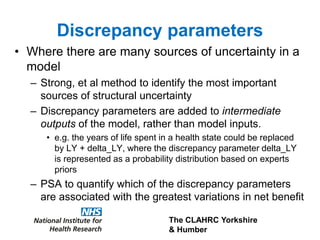

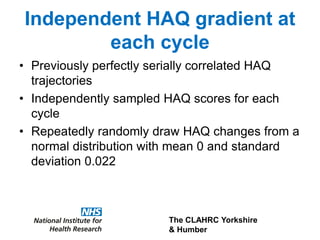

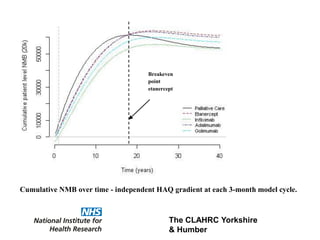

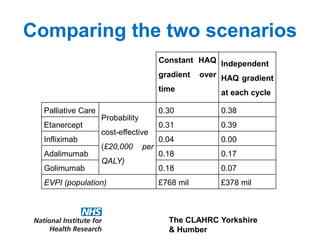

3) The document presents approaches for characterizing and addressing extrapolation uncertainty, such as assessing model fit and plausibility, scenario analysis, model averaging, and incorporating expert elicitation. Addressing uncertainty is important for reimbursement decisions.