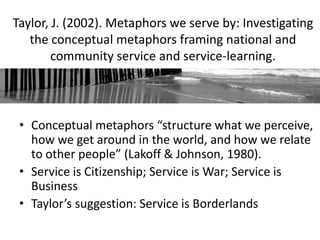

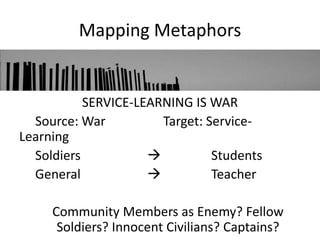

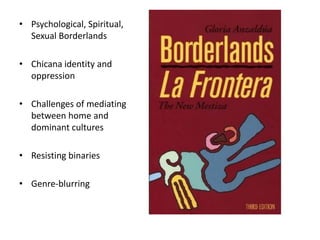

1) How conceptual metaphors like "service is citizenship" frame understandings of service but that "service as borderlands" provides a richer metaphor.

2) The experiences of "border students" who navigate both service sites and universities, feeling a sense of belonging or not belonging in both spaces.

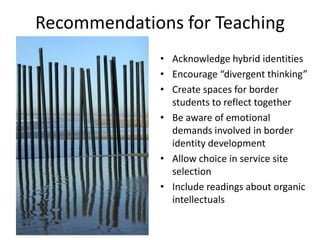

3) Recommendations for teaching and research that acknowledge hybrid identities and create spaces for reflection to better support border students.

![“The prohibited and forbidden are its [the Borderlands’] inhabitants. Los

atravesados live here: the squint-eyed, the perverse, the queer, the

troublesome, the mongrel, the mulatto, the half-breed, the half dead; in

short, those who cross over, pass over, or go through the confines of the

‘normal’” (pp. 25-26).](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/iarslce2012-120924222952-phpapp01/85/IARSLCE-2012-Borderlands-Theory-in-Service-Learning-Research-8-320.jpg)

![Belonging at the Service Site

• Sites are Comfortable: “home away from home” (Lee, 2005,

p. 6); “more comfortable at their service sites than on

campus” (Green, 2001, p. 25).

• Identification with Clients: “I was once one of them”

(Delgado Bernal, Aleman, & Garavito, 2001, p. 575); “I have

something in common … with them because *we’re+

minorities, most of [us] are from low-income families, and

most of them *would be+ first generation in college” (Lee,

2005, p. 6).

• Stronger Service (McCollum, 2003; Green, 2001): “There is

a sense of validity in what I have to say. I am not pretending

to understand, I do understand” (Shadduck-Hernandez,

2006, p. 30).](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/iarslce2012-120924222952-phpapp01/85/IARSLCE-2012-Borderlands-Theory-in-Service-Learning-Research-13-320.jpg)