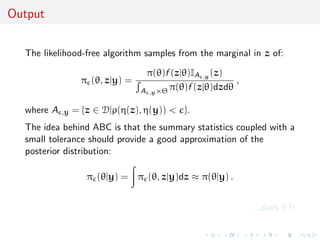

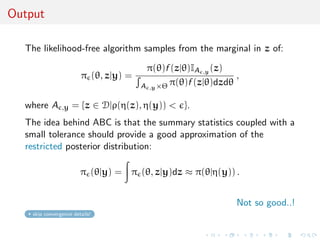

Approximate Bayesian computation (ABC) is a new empirical Bayes method for performing Bayesian inference when the likelihood function is intractable or unavailable in closed form. ABC replaces the likelihood with a non-parametric approximation based on simulating data under different parameter values and comparing simulated and observed data using summary statistics. This allows Bayesian inference to be performed even when direct calculation of the likelihood is not possible. However, ABC introduces an approximation error that is unknown without extensive simulation. Some view ABC as a true Bayesian approach for an estimated or noisy likelihood, while others see it as more of a computational technique that is only approximately Bayesian.

![Outline

Unavailable likelihoods

ABC methods

ABC as an inference machine

[A]BCel

Conclusion and perspectives](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/i-like-130515231914-phpapp01/85/slides-of-ABC-talk-at-i-like-workshop-Warwick-May-16-3-320.jpg)

![summary as an answer to Lange, Chi & Zhou [ISR, 2013]

“Surprisingly, the confident prediction of the previous generation that Bayesian methods would

ultimately supplant frequentist methods has given way to a realization that Markov chain Monte

Carlo (MCMC) may be too slow to handle modern data sets. Size matters because large data sets

stress computer storage and processing power to the breaking point. The most successful

compromises between Bayesian and frequentist methods now rely on penalization and

optimization.”

sad reality constraint that size does matter

focus on much smaller dimensions and on sparse summaries

many (fast) ways of producing those summaries

Bayesian inference can kick in almost automatically at this

stage](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/i-like-130515231914-phpapp01/85/slides-of-ABC-talk-at-i-like-workshop-Warwick-May-16-12-320.jpg)

![summary as an answer to Lange, Chi & Zhou [ISR, 2013]

“Surprisingly, the confident prediction of the previous generation that Bayesian methods would

ultimately supplant frequentist methods has given way to a realization that Markov chain Monte

Carlo (MCMC) may be too slow to handle modern data sets. Size matters because large data sets

stress computer storage and processing power to the breaking point. The most successful

compromises between Bayesian and frequentist methods now rely on penalization and

optimization.”

sad reality constraint that size does matter

focus on much smaller dimensions and on sparse summaries

many (fast) ways of producing those summaries

Bayesian inference can kick in almost automatically at this

stage](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/i-like-130515231914-phpapp01/85/slides-of-ABC-talk-at-i-like-workshop-Warwick-May-16-13-320.jpg)

![Econom’ections

Similar exploration of simulation-based and approximation

techniques in Econometrics

Simulated method of moments

Method of simulated moments

Simulated pseudo-maximum-likelihood

Indirect inference

[Gouri´eroux & Monfort, 1996]

even though motivation is partly-defined models rather than

complex likelihoods](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/i-like-130515231914-phpapp01/85/slides-of-ABC-talk-at-i-like-workshop-Warwick-May-16-14-320.jpg)

![Econom’ections

Similar exploration of simulation-based and approximation

techniques in Econometrics

Simulated method of moments

Method of simulated moments

Simulated pseudo-maximum-likelihood

Indirect inference

[Gouri´eroux & Monfort, 1996]

even though motivation is partly-defined models rather than

complex likelihoods](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/i-like-130515231914-phpapp01/85/slides-of-ABC-talk-at-i-like-workshop-Warwick-May-16-15-320.jpg)

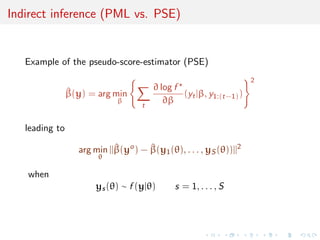

![Indirect inference

Minimise [in θ] a distance between estimators ^β based on a

pseudo-model for genuine observations and for observations

simulated under the true model and the parameter θ.

[Gouri´eroux, Monfort, & Renault, 1993;

Smith, 1993; Gallant & Tauchen, 1996]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/i-like-130515231914-phpapp01/85/slides-of-ABC-talk-at-i-like-workshop-Warwick-May-16-16-320.jpg)

![Consistent indirect inference

“...in order to get a unique solution the dimension of

the auxiliary parameter β must be larger than or equal to

the dimension of the initial parameter θ. If the problem is

just identified the different methods become easier...”

Consistency depending on the criterion and on the asymptotic

identifiability of θ

[Gouri´eroux & Monfort, 1996, p. 66]

Which connection [if any] with the B perspective?](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/i-like-130515231914-phpapp01/85/slides-of-ABC-talk-at-i-like-workshop-Warwick-May-16-19-320.jpg)

![Consistent indirect inference

“...in order to get a unique solution the dimension of

the auxiliary parameter β must be larger than or equal to

the dimension of the initial parameter θ. If the problem is

just identified the different methods become easier...”

Consistency depending on the criterion and on the asymptotic

identifiability of θ

[Gouri´eroux & Monfort, 1996, p. 66]

Which connection [if any] with the B perspective?](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/i-like-130515231914-phpapp01/85/slides-of-ABC-talk-at-i-like-workshop-Warwick-May-16-20-320.jpg)

![Consistent indirect inference

“...in order to get a unique solution the dimension of

the auxiliary parameter β must be larger than or equal to

the dimension of the initial parameter θ. If the problem is

just identified the different methods become easier...”

Consistency depending on the criterion and on the asymptotic

identifiability of θ

[Gouri´eroux & Monfort, 1996, p. 66]

Which connection [if any] with the B perspective?](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/i-like-130515231914-phpapp01/85/slides-of-ABC-talk-at-i-like-workshop-Warwick-May-16-21-320.jpg)

![Approximate Bayesian computation

Unavailable likelihoods

ABC methods

Genesis of ABC

ABC basics

Advances and interpretations

ABC as knn

ABC as an inference machine

[A]BCel

Conclusion and perspectives](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/i-like-130515231914-phpapp01/85/slides-of-ABC-talk-at-i-like-workshop-Warwick-May-16-22-320.jpg)

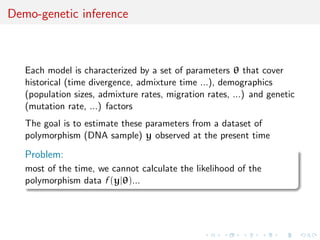

![Genetic background of ABC

skip genetics

ABC is a recent computational technique that only requires being

able to sample from the likelihood f (·|θ)

This technique stemmed from population genetics models, about

15 years ago, and population geneticists still contribute

significantly to methodological developments of ABC.

[Griffith & al., 1997; Tavar´e & al., 1999]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/i-like-130515231914-phpapp01/85/slides-of-ABC-talk-at-i-like-workshop-Warwick-May-16-23-320.jpg)

![Intractable likelihood

Missing (too much missing!) data structure:

f (y|θ) =

G

f (y|G, θ)f (G|θ)dG

cannot be computed in a manageable way...

[Stephens & Donnelly, 2000]

The genealogies are considered as nuisance parameters

This modelling clearly differs from the phylogenetic perspective

where the tree is the parameter of interest.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/i-like-130515231914-phpapp01/85/slides-of-ABC-talk-at-i-like-workshop-Warwick-May-16-31-320.jpg)

![Intractable likelihood

Missing (too much missing!) data structure:

f (y|θ) =

G

f (y|G, θ)f (G|θ)dG

cannot be computed in a manageable way...

[Stephens & Donnelly, 2000]

The genealogies are considered as nuisance parameters

This modelling clearly differs from the phylogenetic perspective

where the tree is the parameter of interest.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/i-like-130515231914-phpapp01/85/slides-of-ABC-talk-at-i-like-workshop-Warwick-May-16-32-320.jpg)

![A?B?C?

A stands for approximate

[wrong likelihood / pic?]

B stands for Bayesian

C stands for computation

[producing a parameter

sample]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/i-like-130515231914-phpapp01/85/slides-of-ABC-talk-at-i-like-workshop-Warwick-May-16-33-320.jpg)

![A?B?C?

A stands for approximate

[wrong likelihood / pic?]

B stands for Bayesian

C stands for computation

[producing a parameter

sample]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/i-like-130515231914-phpapp01/85/slides-of-ABC-talk-at-i-like-workshop-Warwick-May-16-34-320.jpg)

![A?B?C?

A stands for approximate

[wrong likelihood / pic?]

B stands for Bayesian

C stands for computation

[producing a parameter

sample]

ESS=155.6

θ

Density

−0.5 0.0 0.5 1.0

0.01.0

ESS=75.93

θ

Density

−0.4 −0.2 0.0 0.2 0.4

0.01.02.0

ESS=76.87

θ

Density

−0.4 −0.2 0.0 0.2

01234

ESS=91.54

θ

Density

−0.6 −0.4 −0.2 0.0 0.2

01234

ESS=108.4

θ

Density

−0.4 0.0 0.2 0.4 0.6

0.01.02.03.0

ESS=85.13

θ

Density

−0.2 0.0 0.2 0.4 0.6

0.01.02.03.0

ESS=149.1

θ

Density

−0.5 0.0 0.5 1.0

0.01.02.0

ESS=96.31

θ

Density

−0.4 0.0 0.2 0.4 0.6

0.01.02.0

ESS=83.77

θ

Density

−0.6 −0.4 −0.2 0.0 0.2 0.4

01234

ESS=155.7

θ

Density

−0.5 0.0 0.5

0.01.02.0

ESS=92.42

θ

Density

−0.4 0.0 0.2 0.4 0.6

0.01.02.03.0

ESS=95.01

θ

Density

−0.4 0.0 0.2 0.4 0.6

0.01.53.0

ESS=139.2

Density −0.6 −0.2 0.2 0.6

0.01.02.0

ESS=99.33

Density

−0.4 −0.2 0.0 0.2 0.4

0.01.02.03.0

ESS=87.28

Density

−0.2 0.0 0.2 0.4 0.6

0123](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/i-like-130515231914-phpapp01/85/slides-of-ABC-talk-at-i-like-workshop-Warwick-May-16-35-320.jpg)

![ABC methodology

Bayesian setting: target is π(θ)f (x|θ)

When likelihood f (x|θ) not in closed form, likelihood-free rejection

technique:

Foundation

For an observation y ∼ f (y|θ), under the prior π(θ), if one keeps

jointly simulating

θ ∼ π(θ) , z ∼ f (z|θ ) ,

until the auxiliary variable z is equal to the observed value, z = y,

then the selected

θ ∼ π(θ|y)

[Rubin, 1984; Diggle & Gratton, 1984; Tavar´e et al., 1997]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/i-like-130515231914-phpapp01/85/slides-of-ABC-talk-at-i-like-workshop-Warwick-May-16-37-320.jpg)

![ABC methodology

Bayesian setting: target is π(θ)f (x|θ)

When likelihood f (x|θ) not in closed form, likelihood-free rejection

technique:

Foundation

For an observation y ∼ f (y|θ), under the prior π(θ), if one keeps

jointly simulating

θ ∼ π(θ) , z ∼ f (z|θ ) ,

until the auxiliary variable z is equal to the observed value, z = y,

then the selected

θ ∼ π(θ|y)

[Rubin, 1984; Diggle & Gratton, 1984; Tavar´e et al., 1997]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/i-like-130515231914-phpapp01/85/slides-of-ABC-talk-at-i-like-workshop-Warwick-May-16-38-320.jpg)

![ABC methodology

Bayesian setting: target is π(θ)f (x|θ)

When likelihood f (x|θ) not in closed form, likelihood-free rejection

technique:

Foundation

For an observation y ∼ f (y|θ), under the prior π(θ), if one keeps

jointly simulating

θ ∼ π(θ) , z ∼ f (z|θ ) ,

until the auxiliary variable z is equal to the observed value, z = y,

then the selected

θ ∼ π(θ|y)

[Rubin, 1984; Diggle & Gratton, 1984; Tavar´e et al., 1997]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/i-like-130515231914-phpapp01/85/slides-of-ABC-talk-at-i-like-workshop-Warwick-May-16-39-320.jpg)

![A as A...pproximative

When y is a continuous random variable, strict equality z = y is

replaced with a tolerance zone

ρ(y, z)

where ρ is a distance

Output distributed from

π(θ) Pθ{ρ(y, z) < }

def

∝ π(θ|ρ(y, z) < )

[Pritchard et al., 1999]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/i-like-130515231914-phpapp01/85/slides-of-ABC-talk-at-i-like-workshop-Warwick-May-16-40-320.jpg)

![A as A...pproximative

When y is a continuous random variable, strict equality z = y is

replaced with a tolerance zone

ρ(y, z)

where ρ is a distance

Output distributed from

π(θ) Pθ{ρ(y, z) < }

def

∝ π(θ|ρ(y, z) < )

[Pritchard et al., 1999]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/i-like-130515231914-phpapp01/85/slides-of-ABC-talk-at-i-like-workshop-Warwick-May-16-41-320.jpg)

![ABC (simul’) advances

how approximative is ABC? ABC as knn

Simulating from the prior is often poor in efficiency

Either modify the proposal distribution on θ to increase the density

of x’s within the vicinity of y...

[Marjoram et al, 2003; Bortot et al., 2007, Sisson et al., 2007]

...or by viewing the problem as a conditional density estimation

and by developing techniques to allow for larger

[Beaumont et al., 2002]

.....or even by including in the inferential framework [ABCµ]

[Ratmann et al., 2009]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/i-like-130515231914-phpapp01/85/slides-of-ABC-talk-at-i-like-workshop-Warwick-May-16-53-320.jpg)

![ABC (simul’) advances

how approximative is ABC? ABC as knn

Simulating from the prior is often poor in efficiency

Either modify the proposal distribution on θ to increase the density

of x’s within the vicinity of y...

[Marjoram et al, 2003; Bortot et al., 2007, Sisson et al., 2007]

...or by viewing the problem as a conditional density estimation

and by developing techniques to allow for larger

[Beaumont et al., 2002]

.....or even by including in the inferential framework [ABCµ]

[Ratmann et al., 2009]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/i-like-130515231914-phpapp01/85/slides-of-ABC-talk-at-i-like-workshop-Warwick-May-16-54-320.jpg)

![ABC (simul’) advances

how approximative is ABC? ABC as knn

Simulating from the prior is often poor in efficiency

Either modify the proposal distribution on θ to increase the density

of x’s within the vicinity of y...

[Marjoram et al, 2003; Bortot et al., 2007, Sisson et al., 2007]

...or by viewing the problem as a conditional density estimation

and by developing techniques to allow for larger

[Beaumont et al., 2002]

.....or even by including in the inferential framework [ABCµ]

[Ratmann et al., 2009]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/i-like-130515231914-phpapp01/85/slides-of-ABC-talk-at-i-like-workshop-Warwick-May-16-55-320.jpg)

![ABC (simul’) advances

how approximative is ABC? ABC as knn

Simulating from the prior is often poor in efficiency

Either modify the proposal distribution on θ to increase the density

of x’s within the vicinity of y...

[Marjoram et al, 2003; Bortot et al., 2007, Sisson et al., 2007]

...or by viewing the problem as a conditional density estimation

and by developing techniques to allow for larger

[Beaumont et al., 2002]

.....or even by including in the inferential framework [ABCµ]

[Ratmann et al., 2009]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/i-like-130515231914-phpapp01/85/slides-of-ABC-talk-at-i-like-workshop-Warwick-May-16-56-320.jpg)

![ABC-NP

Better usage of [prior] simulations by

adjustement: instead of throwing away

θ such that ρ(η(z), η(y)) > , replace

θ’s with locally regressed transforms

θ∗

= θ − {η(z) − η(y)}T ^β

[Csill´ery et al., TEE, 2010]

where ^β is obtained by [NP] weighted least square regression on

(η(z) − η(y)) with weights

Kδ {ρ(η(z), η(y))}

[Beaumont et al., 2002, Genetics]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/i-like-130515231914-phpapp01/85/slides-of-ABC-talk-at-i-like-workshop-Warwick-May-16-57-320.jpg)

![ABC-NP (regression)

Also found in the subsequent literature, e.g. in Fearnhead-Prangle (2012) :

weight directly simulation by

Kδ {ρ(η(z(θ)), η(y))}

or

1

S

S

s=1

Kδ {ρ(η(zs

(θ)), η(y))}

[consistent estimate of f (η|θ)]

Curse of dimensionality: poor estimate when d = dim(η) is large...](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/i-like-130515231914-phpapp01/85/slides-of-ABC-talk-at-i-like-workshop-Warwick-May-16-58-320.jpg)

![ABC-NP (regression)

Also found in the subsequent literature, e.g. in Fearnhead-Prangle (2012) :

weight directly simulation by

Kδ {ρ(η(z(θ)), η(y))}

or

1

S

S

s=1

Kδ {ρ(η(zs

(θ)), η(y))}

[consistent estimate of f (η|θ)]

Curse of dimensionality: poor estimate when d = dim(η) is large...](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/i-like-130515231914-phpapp01/85/slides-of-ABC-talk-at-i-like-workshop-Warwick-May-16-59-320.jpg)

![ABC-NP (density estimation)

Use of the kernel weights

Kδ {ρ(η(z(θ)), η(y))}

leads to the NP estimate of the posterior expectation

i θi Kδ {ρ(η(z(θi )), η(y))}

i Kδ {ρ(η(z(θi )), η(y))}

[Blum, JASA, 2010]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/i-like-130515231914-phpapp01/85/slides-of-ABC-talk-at-i-like-workshop-Warwick-May-16-60-320.jpg)

![ABC-NP (density estimation)

Use of the kernel weights

Kδ {ρ(η(z(θ)), η(y))}

leads to the NP estimate of the posterior conditional density

i

˜Kb(θi − θ)Kδ {ρ(η(z(θi )), η(y))}

i Kδ {ρ(η(z(θi )), η(y))}

[Blum, JASA, 2010]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/i-like-130515231914-phpapp01/85/slides-of-ABC-talk-at-i-like-workshop-Warwick-May-16-61-320.jpg)

![ABC-NP (density estimations)

Other versions incorporating regression adjustments

i

˜Kb(θ∗

i − θ)Kδ {ρ(η(z(θi )), η(y))}

i Kδ {ρ(η(z(θi )), η(y))}

In all cases, error

E[^g(θ|y)] − g(θ|y) = cb2

+ cδ2

+ OP(b2

+ δ2

) + OP(1/nδd

)

var(^g(θ|y)) =

c

nbδd

(1 + oP(1))](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/i-like-130515231914-phpapp01/85/slides-of-ABC-talk-at-i-like-workshop-Warwick-May-16-62-320.jpg)

![ABC-NP (density estimations)

Other versions incorporating regression adjustments

i

˜Kb(θ∗

i − θ)Kδ {ρ(η(z(θi )), η(y))}

i Kδ {ρ(η(z(θi )), η(y))}

In all cases, error

E[^g(θ|y)] − g(θ|y) = cb2

+ cδ2

+ OP(b2

+ δ2

) + OP(1/nδd

)

var(^g(θ|y)) =

c

nbδd

(1 + oP(1))

[Blum, JASA, 2010]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/i-like-130515231914-phpapp01/85/slides-of-ABC-talk-at-i-like-workshop-Warwick-May-16-63-320.jpg)

![ABC-NP (density estimations)

Other versions incorporating regression adjustments

i

˜Kb(θ∗

i − θ)Kδ {ρ(η(z(θi )), η(y))}

i Kδ {ρ(η(z(θi )), η(y))}

In all cases, error

E[^g(θ|y)] − g(θ|y) = cb2

+ cδ2

+ OP(b2

+ δ2

) + OP(1/nδd

)

var(^g(θ|y)) =

c

nbδd

(1 + oP(1))

[standard NP calculations]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/i-like-130515231914-phpapp01/85/slides-of-ABC-talk-at-i-like-workshop-Warwick-May-16-64-320.jpg)

![ABC as knn

[Biau et al., 2013, Annales de l’IHP]

Practice of ABC: determine tolerance as a quantile on observed

distances, say 10% or 1% quantile,

= N = qα(d1, . . . , dN)

Interpretation of ε as nonparametric bandwidth only

approximation of the actual practice

[Blum & Fran¸cois, 2010]

ABC is a k-nearest neighbour (knn) method with kN = N N

[Loftsgaarden & Quesenberry, 1965]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/i-like-130515231914-phpapp01/85/slides-of-ABC-talk-at-i-like-workshop-Warwick-May-16-65-320.jpg)

![ABC as knn

[Biau et al., 2013, Annales de l’IHP]

Practice of ABC: determine tolerance as a quantile on observed

distances, say 10% or 1% quantile,

= N = qα(d1, . . . , dN)

Interpretation of ε as nonparametric bandwidth only

approximation of the actual practice

[Blum & Fran¸cois, 2010]

ABC is a k-nearest neighbour (knn) method with kN = N N

[Loftsgaarden & Quesenberry, 1965]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/i-like-130515231914-phpapp01/85/slides-of-ABC-talk-at-i-like-workshop-Warwick-May-16-66-320.jpg)

![ABC as knn

[Biau et al., 2013, Annales de l’IHP]

Practice of ABC: determine tolerance as a quantile on observed

distances, say 10% or 1% quantile,

= N = qα(d1, . . . , dN)

Interpretation of ε as nonparametric bandwidth only

approximation of the actual practice

[Blum & Fran¸cois, 2010]

ABC is a k-nearest neighbour (knn) method with kN = N N

[Loftsgaarden & Quesenberry, 1965]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/i-like-130515231914-phpapp01/85/slides-of-ABC-talk-at-i-like-workshop-Warwick-May-16-67-320.jpg)

![ABC consistency

Provided

kN/ log log N −→ ∞ and kN/N −→ 0

as N → ∞, for almost all s0 (with respect to the distribution of

S), with probability 1,

1

kN

kN

j=1

ϕ(θj ) −→ E[ϕ(θj )|S = s0]

[Devroye, 1982]

Biau et al. (2012) also recall pointwise and integrated mean square error

consistency results on the corresponding kernel estimate of the

conditional posterior distribution, under constraints

kN → ∞, kN /N → 0, hN → 0 and hp

N kN → ∞,](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/i-like-130515231914-phpapp01/85/slides-of-ABC-talk-at-i-like-workshop-Warwick-May-16-68-320.jpg)

![ABC consistency

Provided

kN/ log log N −→ ∞ and kN/N −→ 0

as N → ∞, for almost all s0 (with respect to the distribution of

S), with probability 1,

1

kN

kN

j=1

ϕ(θj ) −→ E[ϕ(θj )|S = s0]

[Devroye, 1982]

Biau et al. (2012) also recall pointwise and integrated mean square error

consistency results on the corresponding kernel estimate of the

conditional posterior distribution, under constraints

kN → ∞, kN /N → 0, hN → 0 and hp

N kN → ∞,](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/i-like-130515231914-phpapp01/85/slides-of-ABC-talk-at-i-like-workshop-Warwick-May-16-69-320.jpg)

![Rates of convergence

Further assumptions (on target and kernel) allow for precise

(integrated mean square) convergence rates (as a power of the

sample size N), derived from classical k-nearest neighbour

regression, like

when m = 1, 2, 3, kN ≈ N(p+4)/(p+8) and rate N− 4

p+8

when m = 4, kN ≈ N(p+4)/(p+8) and rate N− 4

p+8 log N

when m > 4, kN ≈ N(p+4)/(m+p+4) and rate N− 4

m+p+4

[Biau et al., 2012, arxiv:1207.6461]

Drag: Only applies to sufficient summary statistics](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/i-like-130515231914-phpapp01/85/slides-of-ABC-talk-at-i-like-workshop-Warwick-May-16-70-320.jpg)

![Rates of convergence

Further assumptions (on target and kernel) allow for precise

(integrated mean square) convergence rates (as a power of the

sample size N), derived from classical k-nearest neighbour

regression, like

when m = 1, 2, 3, kN ≈ N(p+4)/(p+8) and rate N− 4

p+8

when m = 4, kN ≈ N(p+4)/(p+8) and rate N− 4

p+8 log N

when m > 4, kN ≈ N(p+4)/(m+p+4) and rate N− 4

m+p+4

[Biau et al., 2012, arxiv:1207.6461]

Drag: Only applies to sufficient summary statistics](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/i-like-130515231914-phpapp01/85/slides-of-ABC-talk-at-i-like-workshop-Warwick-May-16-71-320.jpg)

![ABC inference machine

Unavailable likelihoods

ABC methods

ABC as an inference machine

Error inc.

Exact BC and approximate

targets

summary statistic

[A]BCel

Conclusion and perspectives](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/i-like-130515231914-phpapp01/85/slides-of-ABC-talk-at-i-like-workshop-Warwick-May-16-72-320.jpg)

![ABCµ

Idea Infer about the error as well as about the parameter:

Use of a joint density

f (θ, |y) ∝ ξ( |y, θ) × πθ(θ) × π ( )

where y is the data, and ξ( |y, θ) is the prior predictive density of

ρ(η(z), η(y)) given θ and y when z ∼ f (z|θ)

Warning! Replacement of ξ( |y, θ) with a non-parametric kernel

approximation.

[Ratmann, Andrieu, Wiuf and Richardson, 2009, PNAS]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/i-like-130515231914-phpapp01/85/slides-of-ABC-talk-at-i-like-workshop-Warwick-May-16-74-320.jpg)

![ABCµ

Idea Infer about the error as well as about the parameter:

Use of a joint density

f (θ, |y) ∝ ξ( |y, θ) × πθ(θ) × π ( )

where y is the data, and ξ( |y, θ) is the prior predictive density of

ρ(η(z), η(y)) given θ and y when z ∼ f (z|θ)

Warning! Replacement of ξ( |y, θ) with a non-parametric kernel

approximation.

[Ratmann, Andrieu, Wiuf and Richardson, 2009, PNAS]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/i-like-130515231914-phpapp01/85/slides-of-ABC-talk-at-i-like-workshop-Warwick-May-16-75-320.jpg)

![ABCµ

Idea Infer about the error as well as about the parameter:

Use of a joint density

f (θ, |y) ∝ ξ( |y, θ) × πθ(θ) × π ( )

where y is the data, and ξ( |y, θ) is the prior predictive density of

ρ(η(z), η(y)) given θ and y when z ∼ f (z|θ)

Warning! Replacement of ξ( |y, θ) with a non-parametric kernel

approximation.

[Ratmann, Andrieu, Wiuf and Richardson, 2009, PNAS]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/i-like-130515231914-phpapp01/85/slides-of-ABC-talk-at-i-like-workshop-Warwick-May-16-76-320.jpg)

![ABCµ details

Multidimensional distances ρk (k = 1, . . . , K) and errors

k = ρk(ηk(z), ηk(y)), with

k ∼ ξk( |y, θ) ≈ ^ξk( |y, θ) =

1

Bhk

b

K[{ k−ρk(ηk(zb), ηk(y))}/hk]

then used in replacing ξ( |y, θ) with mink

^ξk( |y, θ)

ABCµ involves acceptance probability

π(θ , )

π(θ, )

q(θ , θ)q( , )

q(θ, θ )q( , )

mink

^ξk( |y, θ )

mink

^ξk( |y, θ)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/i-like-130515231914-phpapp01/85/slides-of-ABC-talk-at-i-like-workshop-Warwick-May-16-77-320.jpg)

![ABCµ details

Multidimensional distances ρk (k = 1, . . . , K) and errors

k = ρk(ηk(z), ηk(y)), with

k ∼ ξk( |y, θ) ≈ ^ξk( |y, θ) =

1

Bhk

b

K[{ k−ρk(ηk(zb), ηk(y))}/hk]

then used in replacing ξ( |y, θ) with mink

^ξk( |y, θ)

ABCµ involves acceptance probability

π(θ , )

π(θ, )

q(θ , θ)q( , )

q(θ, θ )q( , )

mink

^ξk( |y, θ )

mink

^ξk( |y, θ)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/i-like-130515231914-phpapp01/85/slides-of-ABC-talk-at-i-like-workshop-Warwick-May-16-78-320.jpg)

![Wilkinson’s exact BC (not exactly!)

ABC approximation error (i.e. non-zero tolerance) replaced with

exact simulation from a controlled approximation to the target,

convolution of true posterior with kernel function

π (θ, z|y) =

π(θ)f (z|θ)K (y − z)

π(θ)f (z|θ)K (y − z)dzdθ

,

with K kernel parameterised by bandwidth .

[Wilkinson, 2013]

Theorem

The ABC algorithm based on the assumption of a randomised

observation y = ˜y + ξ, ξ ∼ K , and an acceptance probability of

K (y − z)/M

gives draws from the posterior distribution π(θ|y).](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/i-like-130515231914-phpapp01/85/slides-of-ABC-talk-at-i-like-workshop-Warwick-May-16-79-320.jpg)

![Wilkinson’s exact BC (not exactly!)

ABC approximation error (i.e. non-zero tolerance) replaced with

exact simulation from a controlled approximation to the target,

convolution of true posterior with kernel function

π (θ, z|y) =

π(θ)f (z|θ)K (y − z)

π(θ)f (z|θ)K (y − z)dzdθ

,

with K kernel parameterised by bandwidth .

[Wilkinson, 2013]

Theorem

The ABC algorithm based on the assumption of a randomised

observation y = ˜y + ξ, ξ ∼ K , and an acceptance probability of

K (y − z)/M

gives draws from the posterior distribution π(θ|y).](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/i-like-130515231914-phpapp01/85/slides-of-ABC-talk-at-i-like-workshop-Warwick-May-16-80-320.jpg)

![How exact a BC?

Pros

Pseudo-data from true model and observed data from noisy

model

Interesting perspective in that outcome is completely

controlled

Link with ABCµ and assuming y is observed with a

measurement error with density K

Relates to the theory of model approximation

[Kennedy & O’Hagan, 2001]

leads to “noisy ABC”: perturbates the data down to precision

ε and proceed

[Fearnhead & Prangle, 2012]

Cons

Requires K to be bounded by M

True approximation error never assessed](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/i-like-130515231914-phpapp01/85/slides-of-ABC-talk-at-i-like-workshop-Warwick-May-16-81-320.jpg)

![How exact a BC?

Pros

Pseudo-data from true model and observed data from noisy

model

Interesting perspective in that outcome is completely

controlled

Link with ABCµ and assuming y is observed with a

measurement error with density K

Relates to the theory of model approximation

[Kennedy & O’Hagan, 2001]

leads to “noisy ABC”: perturbates the data down to precision

ε and proceed

[Fearnhead & Prangle, 2012]

Cons

Requires K to be bounded by M

True approximation error never assessed](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/i-like-130515231914-phpapp01/85/slides-of-ABC-talk-at-i-like-workshop-Warwick-May-16-82-320.jpg)

![Noisy ABC for HMMs

Specific case of a hidden Markov model summaries

Xt+1 ∼ Qθ(Xt, ·)

Yt+1 ∼ gθ(·|xt)

where only y0

1:n is observed.

[Dean, Singh, Jasra, & Peters, 2011]

Use of specific constraints, adapted to the Markov structure:

y1 ∈ B(y0

1 , ) × · · · × yn ∈ B(y0

n , )](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/i-like-130515231914-phpapp01/85/slides-of-ABC-talk-at-i-like-workshop-Warwick-May-16-83-320.jpg)

![Noisy ABC for HMMs

Specific case of a hidden Markov model summaries

Xt+1 ∼ Qθ(Xt, ·)

Yt+1 ∼ gθ(·|xt)

where only y0

1:n is observed.

[Dean, Singh, Jasra, & Peters, 2011]

Use of specific constraints, adapted to the Markov structure:

y1 ∈ B(y0

1 , ) × · · · × yn ∈ B(y0

n , )](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/i-like-130515231914-phpapp01/85/slides-of-ABC-talk-at-i-like-workshop-Warwick-May-16-84-320.jpg)

![Noisy ABC-MLE

Idea: Modify instead the data from the start

(y0

1 + ζ1, . . . , yn + ζn)

[ see Fearnhead-Prangle ]

noisy ABC-MLE estimate

arg max

θ

Pθ Y1 ∈ B(y0

1 + ζ1, ), . . . , Yn ∈ B(y0

n + ζn, )

[Dean, Singh, Jasra, & Peters, 2011]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/i-like-130515231914-phpapp01/85/slides-of-ABC-talk-at-i-like-workshop-Warwick-May-16-85-320.jpg)

![Consistent noisy ABC-MLE

Degrading the data improves the estimation performances:

Noisy ABC-MLE is asymptotically (in n) consistent

under further assumptions, the noisy ABC-MLE is

asymptotically normal

increase in variance of order −2

likely degradation in precision or computing time due to the

lack of summary statistic [curse of dimensionality]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/i-like-130515231914-phpapp01/85/slides-of-ABC-talk-at-i-like-workshop-Warwick-May-16-86-320.jpg)

![Which summary for model choice?

Depending on the choice of η(·), the Bayes factor based on this

insufficient statistic,

Bη

12(y) =

π1(θ1)f η

1 (η(y)|θ1) dθ1

π2(θ2)f η

2 (η(y)|θ2) dθ2

,

is either consistent or inconsistent

[X, Cornuet, Marin, & Pillai, 2012]

Consistency only depends on the range of Ei [η(y)] under both

models

[Marin, Pillai, X, & Rousseau, 2012]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/i-like-130515231914-phpapp01/85/slides-of-ABC-talk-at-i-like-workshop-Warwick-May-16-90-320.jpg)

![Which summary for model choice?

Depending on the choice of η(·), the Bayes factor based on this

insufficient statistic,

Bη

12(y) =

π1(θ1)f η

1 (η(y)|θ1) dθ1

π2(θ2)f η

2 (η(y)|θ2) dθ2

,

is either consistent or inconsistent

[X, Cornuet, Marin, & Pillai, 2012]

Consistency only depends on the range of Ei [η(y)] under both

models

[Marin, Pillai, X, & Rousseau, 2012]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/i-like-130515231914-phpapp01/85/slides-of-ABC-talk-at-i-like-workshop-Warwick-May-16-91-320.jpg)

![Summary [of F&P/statistics)

optimality of the posterior expectation

E[θ|y]

of the parameter of interest as summary statistics η(y)!

[requires iterative process]

use of the standard quadratic loss function

(θ − θ0)T

A(θ − θ0)

recent extension to model choice, optimality of Bayes factor

B12(y)

[F&P, ISBA 2012, Kyoto]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/i-like-130515231914-phpapp01/85/slides-of-ABC-talk-at-i-like-workshop-Warwick-May-16-93-320.jpg)

![Summary [of F&P/statistics)

optimality of the posterior expectation

E[θ|y]

of the parameter of interest as summary statistics η(y)!

[requires iterative process]

use of the standard quadratic loss function

(θ − θ0)T

A(θ − θ0)

recent extension to model choice, optimality of Bayes factor

B12(y)

[F&P, ISBA 2012, Kyoto]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/i-like-130515231914-phpapp01/85/slides-of-ABC-talk-at-i-like-workshop-Warwick-May-16-94-320.jpg)

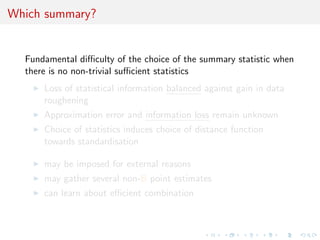

![Summary [about summaries]

Choice of summary statistics is paramount for ABC

validation/performances

At best, ABC approximates π(. | η(y)) [unavoidable]

Model selection feasible with ABC [with caution!]

For estimation, consistency if {θ; µ(θ) = µ0} = θ0 when

Eθ[η(y)] = µ(θ)

For testing consistency if

{µ1(θ1), θ1 ∈ Θ1} ∩ {µ2(θ2), θ2 ∈ Θ2} = ∅

[Marin et al., 2011]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/i-like-130515231914-phpapp01/85/slides-of-ABC-talk-at-i-like-workshop-Warwick-May-16-95-320.jpg)

![Summary [about summaries]

Choice of summary statistics is paramount for ABC

validation/performances

At best, ABC approximates π(. | η(y)) [unavoidable]

Model selection feasible with ABC [with caution!]

For estimation, consistency if {θ; µ(θ) = µ0} = θ0 when

Eθ[η(y)] = µ(θ)

For testing consistency if

{µ1(θ1), θ1 ∈ Θ1} ∩ {µ2(θ2), θ2 ∈ Θ2} = ∅

[Marin et al., 2011]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/i-like-130515231914-phpapp01/85/slides-of-ABC-talk-at-i-like-workshop-Warwick-May-16-96-320.jpg)

![Summary [about summaries]

Choice of summary statistics is paramount for ABC

validation/performances

At best, ABC approximates π(. | η(y)) [unavoidable]

Model selection feasible with ABC [with caution!]

For estimation, consistency if {θ; µ(θ) = µ0} = θ0 when

Eθ[η(y)] = µ(θ)

For testing consistency if

{µ1(θ1), θ1 ∈ Θ1} ∩ {µ2(θ2), θ2 ∈ Θ2} = ∅

[Marin et al., 2011]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/i-like-130515231914-phpapp01/85/slides-of-ABC-talk-at-i-like-workshop-Warwick-May-16-97-320.jpg)

![Summary [about summaries]

Choice of summary statistics is paramount for ABC

validation/performances

At best, ABC approximates π(. | η(y)) [unavoidable]

Model selection feasible with ABC [with caution!]

For estimation, consistency if {θ; µ(θ) = µ0} = θ0 when

Eθ[η(y)] = µ(θ)

For testing consistency if

{µ1(θ1), θ1 ∈ Θ1} ∩ {µ2(θ2), θ2 ∈ Θ2} = ∅

[Marin et al., 2011]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/i-like-130515231914-phpapp01/85/slides-of-ABC-talk-at-i-like-workshop-Warwick-May-16-98-320.jpg)

![Summary [about summaries]

Choice of summary statistics is paramount for ABC

validation/performances

At best, ABC approximates π(. | η(y)) [unavoidable]

Model selection feasible with ABC [with caution!]

For estimation, consistency if {θ; µ(θ) = µ0} = θ0 when

Eθ[η(y)] = µ(θ)

For testing consistency if

{µ1(θ1), θ1 ∈ Θ1} ∩ {µ2(θ2), θ2 ∈ Θ2} = ∅

[Marin et al., 2011]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/i-like-130515231914-phpapp01/85/slides-of-ABC-talk-at-i-like-workshop-Warwick-May-16-99-320.jpg)

![Empirical likelihood (EL)

Unavailable likelihoods

ABC methods

ABC as an inference machine

[A]BCel

ABC and EL

Composite likelihood

Illustrations

Conclusion and perspectives](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/i-like-130515231914-phpapp01/85/slides-of-ABC-talk-at-i-like-workshop-Warwick-May-16-100-320.jpg)

![Empirical likelihood (EL)

Dataset x made of n independent replicates x = (x1, . . . , xn) of

some X ∼ F

Generalized moment condition model

EF h(X, φ) = 0,

where h is a known function, and φ an unknown parameter

Corresponding empirical likelihood

Lel(φ|x) = max

p

n

i=1

pi

for all p such that 0 pi 1, i pi = 1, i pi h(xi , φ) = 0.

[Owen, 1988, Bio’ka, & Empirical Likelihood, 2001]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/i-like-130515231914-phpapp01/85/slides-of-ABC-talk-at-i-like-workshop-Warwick-May-16-101-320.jpg)

![Empirical likelihood (EL)

Dataset x made of n independent replicates x = (x1, . . . , xn) of

some X ∼ F

Generalized moment condition model

EF h(X, φ) = 0,

where h is a known function, and φ an unknown parameter

Corresponding empirical likelihood

Lel(φ|x) = max

p

n

i=1

pi

for all p such that 0 pi 1, i pi = 1, i pi h(xi , φ) = 0.

[Owen, 1988, Bio’ka, & Empirical Likelihood, 2001]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/i-like-130515231914-phpapp01/85/slides-of-ABC-talk-at-i-like-workshop-Warwick-May-16-102-320.jpg)

![Convergence of EL [3.4]

Theorem 3.4 Let X, Y1, . . . , Yn be independent rv’s with common

distribution F0. For θ ∈ Θ, and the function h(X, θ) ∈ Rs, let

θ0 ∈ Θ be such that

Var(h(Yi , θ0))

is finite and has rank q > 0. If θ0 satisfies

E(h(X, θ0)) = 0,

then

−2 log

Lel(θ0|Y1, . . . , Yn)

n−n

→ χ2

(q)

in distribution when n → ∞.

[Owen, 2001]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/i-like-130515231914-phpapp01/85/slides-of-ABC-talk-at-i-like-workshop-Warwick-May-16-103-320.jpg)

![Convergence of EL [3.4]

“...The interesting thing about Theorem 3.4 is what is not there. It

includes no conditions to make ^θ a good estimate of θ0, nor even

conditions to ensure a unique value for θ0, nor even that any solution θ0

exists. Theorem 3.4 applies in the just determined, over-determined, and

under-determined cases. When we can prove that our estimating

equations uniquely define θ0, and provide a consistent estimator ^θ of it,

then confidence regions and tests follow almost automatically through

Theorem 3.4.”.

[Owen, 2001]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/i-like-130515231914-phpapp01/85/slides-of-ABC-talk-at-i-like-workshop-Warwick-May-16-104-320.jpg)

![Raw [A]BCelsampler

Act as if EL was an exact likelihood

[Lazar, 2003]

for i = 1 → N do

generate φi from the prior distribution π(·)

set the weight ωi = Lel(φi |xobs)

end for

return (φi , ωi ), i = 1, . . . , N

Output weighted sample of size N](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/i-like-130515231914-phpapp01/85/slides-of-ABC-talk-at-i-like-workshop-Warwick-May-16-105-320.jpg)

![Raw [A]BCelsampler

Act as if EL was an exact likelihood

[Lazar, 2003]

for i = 1 → N do

generate φi from the prior distribution π(·)

set the weight ωi = Lel(φi |xobs)

end for

return (φi , ωi ), i = 1, . . . , N

Performance evaluated through effective sample size

ESS = 1

N

i=1

ωi

N

j=1

ωj

2](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/i-like-130515231914-phpapp01/85/slides-of-ABC-talk-at-i-like-workshop-Warwick-May-16-106-320.jpg)

![Raw [A]BCelsampler

Act as if EL was an exact likelihood

[Lazar, 2003]

for i = 1 → N do

generate φi from the prior distribution π(·)

set the weight ωi = Lel(φi |xobs)

end for

return (φi , ωi ), i = 1, . . . , N

More advanced algorithms can be adapted to EL:

E.g., adaptive multiple importance sampling (AMIS) of

Cornuet et al. to speed up computations

[Cornuet et al., 2012]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/i-like-130515231914-phpapp01/85/slides-of-ABC-talk-at-i-like-workshop-Warwick-May-16-107-320.jpg)

![Example: normal posterior

[A]BCel with two constraints

ESS=155.6

θ

Density

−0.5 0.0 0.5 1.0

0.01.0

ESS=75.93

θ

Density

−0.4 −0.2 0.0 0.2 0.4

0.01.02.0

ESS=76.87

θ

Density

−0.4 −0.2 0.0 0.2

01234

ESS=91.54

θ

Density

−0.6 −0.4 −0.2 0.0 0.2

01234

ESS=108.4

θ

Density

−0.4 0.0 0.2 0.4 0.6

0.01.02.03.0

ESS=85.13

θ

Density

−0.2 0.0 0.2 0.4 0.6

0.01.02.03.0

ESS=149.1

θ

Density

−0.5 0.0 0.5 1.0

0.01.02.0

ESS=96.31

θ

Density

−0.4 0.0 0.2 0.4 0.6

0.01.02.0

ESS=83.77

θ

Density

−0.6 −0.4 −0.2 0.0 0.2 0.401234

ESS=155.7

θ

Density

−0.5 0.0 0.5

0.01.02.0

ESS=92.42

θ

Density

−0.4 0.0 0.2 0.4 0.6

0.01.02.03.0

ESS=95.01

θ

Density

−0.4 0.0 0.2 0.4 0.6

0.01.53.0

ESS=139.2

Density

−0.6 −0.2 0.2 0.6

0.01.02.0

ESS=99.33

Density

−0.4 −0.2 0.0 0.2 0.4

0.01.02.03.0

ESS=87.28

Density

−0.2 0.0 0.2 0.4 0.6

0123

Sample sizes are of 25 (column 1), 50 (column 2) and 75 (column 3)

observations](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/i-like-130515231914-phpapp01/85/slides-of-ABC-talk-at-i-like-workshop-Warwick-May-16-116-320.jpg)

![Example: normal posterior

[A]BCel with three constraints

ESS=300.1

θ

Density

−0.4 0.0 0.4 0.8

0.01.0

ESS=205.5

θ

Density

−0.6 −0.2 0.0 0.2 0.4

0.01.02.0

ESS=179.4

θ

Density

−0.2 0.0 0.2 0.4

0.01.53.0

ESS=265.1

θ

Density

−0.3 −0.2 −0.1 0.0 0.1

01234

ESS=250.3

θ

Density

−0.6 −0.4 −0.2 0.0 0.2

0.01.02.0

ESS=134.8

θ

Density

−0.4 −0.2 0.0 0.1

01234

ESS=331.5

θ

Density

−0.8 −0.4 0.0 0.4

0.01.02.0

ESS=167.4

θ

Density

−0.9 −0.7 −0.5 −0.3

0123

ESS=136.5

θ

Density

−0.4 −0.2 0.0 0.201234

ESS=322.4

θ

Density

−0.2 0.0 0.2 0.4 0.6 0.8

0.01.02.0

ESS=202.7

θ

Density

−0.4 −0.2 0.0 0.2 0.4

0.01.02.03.0

ESS=166

θ

Density

−0.4 −0.2 0.0 0.2

01234

ESS=263.7

Density

−1.0 −0.6 −0.2

0.01.02.0

ESS=190.9

Density

−0.4 −0.2 0.0 0.2 0.4 0.6

0123

ESS=165.3

Density

−0.5 −0.3 −0.1 0.1

0.01.53.0

Sample sizes are of 25 (column 1), 50 (column 2) and 75 (column 3)

observations](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/i-like-130515231914-phpapp01/85/slides-of-ABC-talk-at-i-like-workshop-Warwick-May-16-117-320.jpg)

![Example: Superposition of gamma processes

Example of superposition of N renewal processes with waiting

times τij (i = 1, . . . , M, j = 1, . . .) ∼ G(α, β), when N is unknown.

Renewal processes

ζi1 = τi1, ζi2 = ζi1 + τi2, . . .

with observations made of first n values of the ζij ’s,

z1 = min{ζij }, z2 = min{ζij ; ζij > z1}, . . .

ending with

zn = min{ζij ; ζij > zn−1} .

[Cox & Kartsonaki, B’ka, 2012]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/i-like-130515231914-phpapp01/85/slides-of-ABC-talk-at-i-like-workshop-Warwick-May-16-118-320.jpg)

![Example: Superposition of gamma processes (ABC)

Interesting testing ground for [A]BCel since data (zt) neither iid

nor Markov

Recovery of an iid structure by

1. simulating a pseudo-dataset,

(z1 , . . . , zn ), as in regular

ABC,

2. deriving sequence of

indicators (ν1, . . . , νn), as

z1 = ζν11, z2 = ζν2j2 , . . .

3. exploiting that those

indicators are distributed

from the prior distribution

on the νt’s leading to an iid

sample of G(α, β) variables

Comparison of ABC and

[A]BCel posteriors

α

Density

0 1 2 3 4

0.00.20.40.60.81.01.21.4

β

Density

0 1 2 3 4

0.00.51.01.5

N

Density

0 5 10 15 20

0.000.020.040.060.08

α

Density

0 1 2 3 4

0.00.51.01.5

β

Density

0 1 2 3 4

0.00.20.40.60.81.0

N

Density

0 5 10 15 20

0.000.010.020.030.040.050.06

Top: [A]BCel

Bottom: regular ABC](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/i-like-130515231914-phpapp01/85/slides-of-ABC-talk-at-i-like-workshop-Warwick-May-16-119-320.jpg)

![Example: Superposition of gamma processes (ABC)

Interesting testing ground for [A]BCel since data (zt) neither iid

nor Markov

Recovery of an iid structure by

1. simulating a pseudo-dataset,

(z1 , . . . , zn ), as in regular

ABC,

2. deriving sequence of

indicators (ν1, . . . , νn), as

z1 = ζν11, z2 = ζν2j2 , . . .

3. exploiting that those

indicators are distributed

from the prior distribution

on the νt’s leading to an iid

sample of G(α, β) variables

Comparison of ABC and

[A]BCel posteriors

α

Density

0 1 2 3 4

0.00.20.40.60.81.01.21.4

β

Density

0 1 2 3 4

0.00.51.01.5

N

Density

0 5 10 15 20

0.000.020.040.060.08

α

Density

0 1 2 3 4

0.00.51.01.5

β

Density

0 1 2 3 4

0.00.20.40.60.81.0

N

Density

0 5 10 15 20

0.000.010.020.030.040.050.06

Top: [A]BCel

Bottom: regular ABC](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/i-like-130515231914-phpapp01/85/slides-of-ABC-talk-at-i-like-workshop-Warwick-May-16-120-320.jpg)

![Pop’gen’: A first experiment

Evolutionary scenario:

MRCA

POP 0 POP 1

τ

Dataset:

50 genes per populations,

100 microsat. loci

Assumptions:

Ne identical over all

populations

φ = (log10 θ, log10 τ)

uniform prior over

(−1., 1.5) × (−1., 1.)

Comparison of the original

ABC with [A]BCel

ESS=7034

log(theta)

Density

0.00 0.05 0.10 0.15 0.20 0.25

051015

log(tau1)

Density

−0.3 −0.2 −0.1 0.0 0.1 0.2 0.3

01234567

histogram = [A]BCel

curve = original ABC

vertical line = “true”

parameter](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/i-like-130515231914-phpapp01/85/slides-of-ABC-talk-at-i-like-workshop-Warwick-May-16-121-320.jpg)

![Pop’gen’: A first experiment

Evolutionary scenario:

MRCA

POP 0 POP 1

τ

Dataset:

50 genes per populations,

100 microsat. loci

Assumptions:

Ne identical over all

populations

φ = (log10 θ, log10 τ)

uniform prior over

(−1., 1.5) × (−1., 1.)

Comparison of the original

ABC with [A]BCel

ESS=7034

log(theta)

Density

0.00 0.05 0.10 0.15 0.20 0.25

051015

log(tau1)

Density

−0.3 −0.2 −0.1 0.0 0.1 0.2 0.3

01234567

histogram = [A]BCel

curve = original ABC

vertical line = “true”

parameter](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/i-like-130515231914-phpapp01/85/slides-of-ABC-talk-at-i-like-workshop-Warwick-May-16-122-320.jpg)

![ABC vs. [A]BCel on 100 replicates of the 1st experiment

Accuracy:

log10 θ log10 τ

ABC [A]BCel ABC [A]BCel

(1) 0.097 0.094 0.315 0.117

(2) 0.071 0.059 0.272 0.077

(3) 0.68 0.81 1.0 0.80

(1) Root Mean Square Error of the posterior mean

(2) Median Absolute Deviation of the posterior median

(3) Coverage of the credibility interval of probability 0.8

Computation time: on a recent 6-core computer

(C++/OpenMP)

ABC ≈ 4 hours

[A]BCel≈ 2 minutes](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/i-like-130515231914-phpapp01/85/slides-of-ABC-talk-at-i-like-workshop-Warwick-May-16-123-320.jpg)

![Pop’gen’: Second experiment

Evolutionary scenario:

MRCA

POP 0 POP 1 POP 2

τ1

τ2

Dataset:

50 genes per populations,

100 microsat. loci

Assumptions:

Ne identical over all

populations

φ =

(log10 θ, log10 τ1, log10 τ2)

non-informative uniform

Comparison of the original ABC

with [A]BCel

histogram = [A]BCel

curve = original ABC

vertical line = “true” parameter](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/i-like-130515231914-phpapp01/85/slides-of-ABC-talk-at-i-like-workshop-Warwick-May-16-124-320.jpg)

![Pop’gen’: Second experiment

Evolutionary scenario:

MRCA

POP 0 POP 1 POP 2

τ1

τ2

Dataset:

50 genes per populations,

100 microsat. loci

Assumptions:

Ne identical over all

populations

φ =

(log10 θ, log10 τ1, log10 τ2)

non-informative uniform

Comparison of the original ABC

with [A]BCel

histogram = [A]BCel

curve = original ABC

vertical line = “true” parameter](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/i-like-130515231914-phpapp01/85/slides-of-ABC-talk-at-i-like-workshop-Warwick-May-16-125-320.jpg)

![Pop’gen’: Second experiment

Evolutionary scenario:

MRCA

POP 0 POP 1 POP 2

τ1

τ2

Dataset:

50 genes per populations,

100 microsat. loci

Assumptions:

Ne identical over all

populations

φ =

(log10 θ, log10 τ1, log10 τ2)

non-informative uniform

Comparison of the original ABC

with [A]BCel

histogram = [A]BCel

curve = original ABC

vertical line = “true” parameter](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/i-like-130515231914-phpapp01/85/slides-of-ABC-talk-at-i-like-workshop-Warwick-May-16-126-320.jpg)

![Pop’gen’: Second experiment

Evolutionary scenario:

MRCA

POP 0 POP 1 POP 2

τ1

τ2

Dataset:

50 genes per populations,

100 microsat. loci

Assumptions:

Ne identical over all

populations

φ =

(log10 θ, log10 τ1, log10 τ2)

non-informative uniform

Comparison of the original ABC

with [A]BCel

histogram = [A]BCel

curve = original ABC

vertical line = “true” parameter](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/i-like-130515231914-phpapp01/85/slides-of-ABC-talk-at-i-like-workshop-Warwick-May-16-127-320.jpg)

![ABC vs. [A]BCel on 100 replicates of the 2nd experiment

Accuracy:

log10 θ log10 τ1 log10 τ2

ABC [A]BCel ABC [A]BCel ABC [A]B

(1) .0059 .0794 .472 .483 29.3 4.7

(2) .048 .053 .32 .28 4.13 3.3

(3) .79 .76 .88 .76 .89 .79

(1) Root Mean Square Error of the posterior mean

(2) Median Absolute Deviation of the posterior median

(3) Coverage of the credibility interval of probability 0.8

Computation time: on a recent 6-core computer

(C++/OpenMP)

ABC ≈ 6 hours

[A]BCel≈ 8 minutes](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/i-like-130515231914-phpapp01/85/slides-of-ABC-talk-at-i-like-workshop-Warwick-May-16-128-320.jpg)

![Comparison

On large datasets, [A]BCel gives more accurate results than ABC

ABC simplifies the dataset through summary statistics

Due to the large dimension of x, the original ABC algorithm

estimates

π θ η(xobs) ,

where η(xobs) is some (non-linear) projection of the observed

dataset on a space with smaller dimension

→ Some information is lost

[A]BCel simplifies the model through a generalized moment

condition model.

→ Here, the moment condition model is based on pairwise

composition likelihood](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/i-like-130515231914-phpapp01/85/slides-of-ABC-talk-at-i-like-workshop-Warwick-May-16-129-320.jpg)

![Conclusion/perspectives

abc part of a wider picture

to handle complex/Big Data

models

many formats of empirical

[likelihood] Bayes methods

available

lack of comparative tools

and of an assessment for

information loss](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/i-like-130515231914-phpapp01/85/slides-of-ABC-talk-at-i-like-workshop-Warwick-May-16-130-320.jpg)