Hydraulic pumping systems use pressurized power fluid to transmit energy downhole to a downhole pump. There are two main types of installations - fixed pumps that are permanently attached, and free pumps that can be circulated in and out of the well. Free pump installations use a bottomhole assembly with a sealing shoe and seals to allow the pump to be run in and out. This allows easy removal of the pump for maintenance or replacement without pulling tubing. The power fluid can be kept separate from produced fluids in a closed-loop system, or mixed together in an open system.

![HYDRAULIC PUMPING 6-11

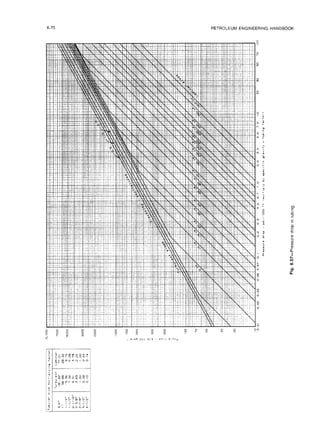

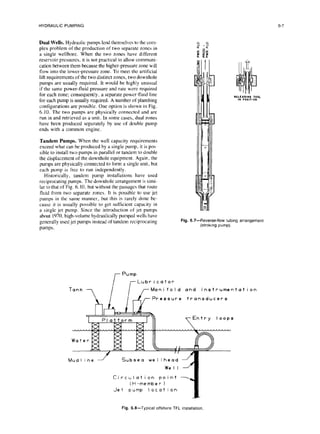

TABLE 6.1~-RECIPROCATING PUMP SPECIFICATIONS. MANUFACTURER “A”

Puma

Type F, Fe, FEB

23/8-in.

tubing

F201311

F201313

F201611

F201613

FE8201613

FE6201616

27/g-h.

tubing

F251611

F251613

F251616

FE252011

FE252013

FE252016

Type VFR

23/8-h.

tubing

VFR201611

VFR201613

VFR201616

VFR20161613

VFR20161616

27/8-h.

tubing

VFR252015

VFR252017

VFR252020

VFR25202015

VFR25202017

VFR25202020

Type V

27/-/n.

tubing

V-25-11-1

i-8

V-25-11-095

V-25-11-076

V-25-11-061

V-25-21-075

V-25-21-063

V-25-21-050

V-25-21-041

Type 220

23/-h. tubing

330-201610

330-201612

530-201615

27/-h. tubing

348-252012

348-252015

548-252017

548-252019

536-252020

Note Pump Size

F. FE, FEB. VFR Types

F

Disolacement

B/D oer strokeslmin

Puma

3.0 4.2

4.2 4.2

3.0 6.4

4.2 6.4

6.2 9.4

9.4 9.4

3.3 7.0

4.6 7.0

7.0 7.0

5.0 16.5

7.0 16.5

10.6 16.5

2.12 4.24

2.96 4.24

4.49 4.24

2.96 6.86

4.49 6.86

5.25 8.89

7.15 8.89

9.33 8.89

5.25 15.16

7.15 15.16

9.33 15.16

6.31 5.33

6.31 6.66

3.93 5.33

3.93 6.66

6.31 8.38

6.31 10.00

3.93 8.38

3.93 10.00

4.22 8.94

5.46 8.94

7.86 8.94

8.73 22.35

12.57 22.35

17.11 22.35

20.17 22.35

25.18 25.18

V Types

v

220 Sertes

3 Number of seals

20 Nommal tubing (2 I” ) 25 Nommal tubmg (2% I” ) 48 Stroke length p,

13 Engme (1 3 I” ) 11 Single engme (double = 21) 25 Nomlnal tubing (2% in.]

XX Second engine (VFR only) 118PIE 20 Engine (2 000 IO.)

11 Pump (1 1 in ) 12 Pump (1 200 m.)

Types F. FE. FEB are slngle-seal, internal-portmg; 220, VFR, and V are multiple-seal, external-pomng.

Engine

Rated Speed (B/D)

Enaine Total PIE

Puma

204

285

204

285

340

517

214

299

455

255

357

540

318

444

673

444

673

630

8.58

1,119

630

858

1,119

1,229

1,299

550

550

1,173

1,072

550

550

422

546

786

629

905

1,232

1,452

2,014

286 490 0.71

286 571 1.00

435 639 0.47

435 720 0.66

517 857 0.66

517 1,034 1.00

455 669 0.47

455 754 0.66

455 910 1.00

842 1,097 0.30

842 1,199 0.42

842 1.382 0.64

636 954 0.62

636 1,080 0.87

636 1,309 1.32

1,029 1,473 0.54

1,029 1,702 0.81

1,067 1,697 0.74

1,067 1,925 1.00

1,067 2,186 1.32

1,819 2,449 0.41

1,819 2,677 0.56

1,819 2,938 0.73

1,098 2,397 1.18

1,372 2,671 0.96

746 1,296 0.76

932 1,482 0.61

1,559 2,732 0.75

I;700 23772 0.63

1,173 1,723 0.50

1,400 1,950 0.41

894 1,316 0.49

894 1,440 0.63

894 1.680 0.89

1,609 2,238 0.40

1.609 2.514 0.57

11609 2,841 0.78

1,609 3,061 0.93

2,014 4,028 1.00

Maximum Rated

Speed

(strokes/min)

68

68

68

68

ii;

65

65

65

51

51

51

150

150

150

150

150

120

120

120

120

120

120

206

206

140

140

186

170

140

140

100

100

100

72

72

72

72

80](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/hydraulicpumping-220105163948/85/Hydraulic-pumping-10-320.jpg)

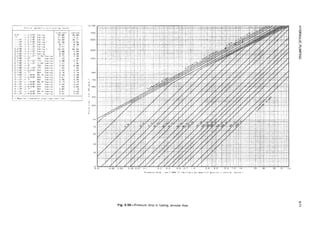

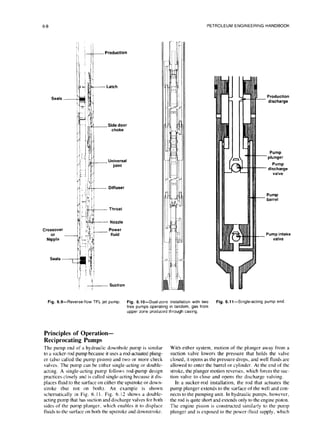

![HYDRAULIC PUMPING 6-17

Powerlift

I Powerlift

II

Fig. 6.17-Manufacturer “C” pump types forTable 6.3

where

F,, = downward force, Ibf,

P,]~ = power-fluid pressure, psi,

A<‘r-

- cross-sectional area of engine rod, sq in.,

AL’,’= cross-sectional area of engine piston.

sq in.,

PP> = pump suction pressure, psi,

A PP = cross-sectional area of pump plunger,

sq in., and

AP’ = cross-sectional area of pump rod, sq in.

The upward forces are

where

F,, = upward force, Ibf,

pcl/ = engine discharge pressure, psi, and

p,,‘l = pump discharge pressure. psi.

900 Series

Fig. &la-Manufacturer “D” pump types forTable 6.4

924 Series

Equating the upward and downward forces and solving

for the power-fluid pressure at the pump gives

P,,~=P<,<I

+P~JA,,~ -A,rY(A,, -A,,.)

-p,u(A, -A,,Y(A, -A<,,). . .(8)

If PPCi

=pF/, as is the case in open power-fluid systems,

then

~,>t.=~,d’ +(A, -A,,V(*,,,, -*,,)I

-P,JA, -A,,V(A, -A,,). .(9)

Eq. 8 can also be written as

P/~=P~,~/+(P~~-P,,~)[(A,,~ -A,,V(A, -Aw)l.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . ..__.. (10)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/hydraulicpumping-220105163948/85/Hydraulic-pumping-16-320.jpg)

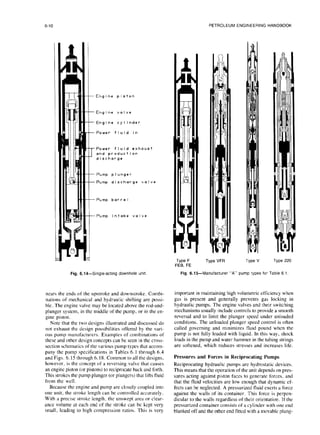

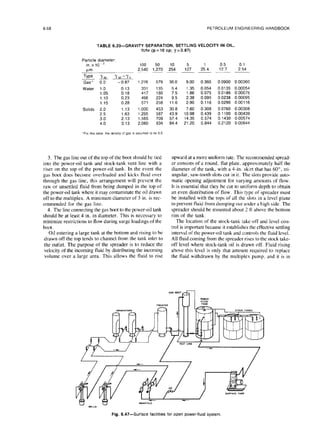

![6-18 PETROLEUM ENGINEERING HANDBOOK

-Force : lb

/

L Area of face of plunger : I in2

f!Fluid pressure = 1000 psi i Fluid pressure : 1000 psi

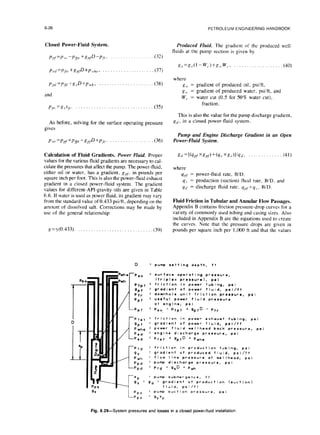

Fig. 6.19-Pressure and force ina static

plunger and cylinder

assembly.

Fig. 6.20-Pressure, force,and flow ina dynamic plunger and

cylinderassembly.

The same analysis for the upstroke would give the same

answer because this double-acting pump is completely

symmetrical.

Fig. 6.23 shows a balanced downhole unit with a single-

acting pump end. First, for the downstroke. the down-

ward forces are

F,I =P,>~(A,,J +p,,, (A,,,, -A,,), __, .(]I)

and the upward forces arc

F,, =P,,/(A,,, -A,,-) +/~,,/(A,,. -AP’.)+p,dA,,,‘)

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . (12)

In this pump. the areas of the engine and pump rods are

half that of their respective pistons and plungers:

A,,.=A,,/2 . . ..(13)

and

A,],.=A,,,J2. (14)

Equating the upward and downward forces, substituting

Eqs. 13 and 14, and solving for the power-fluid pressure.

P,,/ 8 g*ves

~,,~=~,dl +A,~,,IA,)-p,,,(A,,IA,). (15)

Evaluating the force balance for the upstroke gives

F,/ =P c,r/

(Ac,>

)i-p,> (A,,,I-A,,.) _. (16)

and

..,....,,....,,,,.,.,.,.,,, (17)

Eqs. 13. 14, 16, and 17 give

~pr = 21’,></

-p,d 1-A ,,,I/A e,,)-I’,” (A,,, /Ac/l). (18)

Note that if prcf =ppn, which is the case in an open

power-fluid installation, Eqs. 1.5and 18 become the same:

p,,/=~,x/(l +A,/*,,,)-p,,,,(A,,,,IA,). .(19)

Eq. 19 for the single-acting pump shown in Fig. 6.23 can

be made identical to Eq. 9 for the double-acting pump

shown in Fig. 6.22 by observing that, because of Eqs.

13 and 14,

A,/A, =(A,,,, -A,,)/(A, -A,,). . (20)

Because it appears frequently in pressure calculations

with hydraulic pumps, the term (A,,p -A,,,.)/(A,,,l -A,,)

is frequently simplified to P/E. This is sometimes called

the “P over E ratio” of the pump and is the ratio of the

net area of the pump plunger to the net area of the engine

piston. With this nomenclature. Eq. 8 for a closed power-

fluid installation becomes

P/f=Ped +p~d(PIE)-p,,,~(PIE), (21)

where PIE=(A, -*,,.)/(A, -A,,.).

Eq. 9 for an open power-fluid installation becomes

~,,~=p,,(,[ 1+ (PIE)] -pps(PIE). . . (22)

This approach has found widespread acceptance among

the manufacturers of downhole pumps, and the ratio P/E

is included in all their pump specifications (see examples

in Tables 6.1 through 6.4).

P/E values greater than 1.Oindicate that a pump plunger

is larger than the engine piston. This would be appropri-

ate for shallow, low-lift wells. P/E values less than 1.0

are typical of pumps used in deeper. higher-lift wells. In

some pumps, the P/E value is also the ratio of pump dis-

placement to engine displacement, but corrections for fluid](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/hydraulicpumping-220105163948/85/Hydraulic-pumping-17-320.jpg)

![6-28 PETROLEUM ENGINEERING HANDBOOK

Pressure Relationships Used

To Estimate Producing BHP

The pressure relationships of Eqs. 2 1and 22 can be rear-

ranged to give the pump intake pressure p,,, in terms of

the other system pressures and the PIE ratio of the pump.

For the closed power-fluid system,*

For the open power-fluid system,

j7,' =p,,‘/-(p,l,-p,,,,)/(P/E). (49)

If the appropriate relationships from Eqs. 32 through

38 are used. the equation for the closed power-tluid system

becomes**

-(plr,+X,,l.D+P,,h~,)]I(PIE), (50)

where g, =x(1 in a closed power-fluid system.

For the open power-tluid system, the relationship is

-(pf;,+g,,D+P,,,,)]/(P/E). ., ..(51)

These equations can be used directly. but several prob-

lems arise. Several friction terms must be evaluated, each

with a degree of uncertainty. The term p,. for the losses

in the pump is the least accurate number because pump

wear and loading can affect it. To avoid the uncertainty

in friction values. a technique called the “last-stroke

method” is often used. With this method. the power-tluid

supply to the well is shut off. As the pressure in the sys-

tem bleeds down. the pump will continue to stroke at slow-

er rates until it takes its last stroke before stalling out.

The strokes can be observed as small kicks on the power-

fluid pressure gauge at the wellhead. The power-fluid

pressure at the time of the last stroke is that required to

balance all the fluid pressures with zero flow and zero

pump speed. At zero speed. all the friction terms are zero,

cxccpt p/,., which has a minimum value of SOpsi. which

simplifies Eqs. 50 and 5 I. With the friction terms re-

moved, the last stroke relationship for the closed power-

fluid system becomes

(g,,tD+P,,,lrc,)]/(P/E). (52)

For the open power-fluid system the relationship is

-(,~I,D+l,,,.,,)II(PIE). (53)

‘Eq 48 IS dewed from Eq 21 and Eq 49 IS dewed from Eq 22

“Eq 50 IS dewed lrom Eq 21 and Eq 51 IS dewed from Eq 22

These relationships have proved to be very effective in

determining BHP’s. ” However, they are limited to wells

that produce little or no gas for the reasons discussed in

the section on Multiphase Flow and Pump Discharge Pres-

sure. Eqs. 50 and 51 can be used in gassy wells if the

hydrostatic-pressure and flowline-pressure terms arc re-

placed by a pump discharge pressure from a vertical mul-

tiphase flowing gradient correlation. The equations for

the last-stroke method, however, present a further prob-

lem because they require the gradient at a no-flow condi-

tion. The multiphase-flow correlations show a significant

variation of pressure with velocity. Wilson, in Brown,’

suggests subtracting the friction terms from the flowing

gradient for evaluating Eqs. 52 and 53 or attempting to

determine pf,. more accurately for use in the evaluation

of Eqs. 50 and 5 I, The method suggested here is to use

a multiphase-flow correlation for determining ~~~~1

at the

normal operating point of the pump. With the same cor-

relation for the same proportions of liquid and gas, de-

termine what the pPll pressure would be at a low tlow

rate, corresponding to the conditions when the pump is

slowing down to its last stroke. By plotting the two values

of p,,(/ obtained, we can extrapolate to what pprl would

be at zero flow. This value can be used to replace the

hydrostatic-head and flowline-pressure terms.

Selecting an Appropriate PIE Ratio. As previously dis-

cussed, large values of P/E are used in shallow wells and

small values in deeper wells. The larger the value of P/E,

the higher the surface operating pressure to lift fluid

against a given head will be. The multiplex pumps offered

by the manufacturers are rated up to 5,000 psi, but few

hydraulic installations use more than 4,000 psi except in

very deep wells. About 80 to 90% of the installations use

operating pressures between 2,200 and 3,700 psi. With

the simplifying assumptions of an all-water system, no

friction, 500-psi pump friction, 4,000-psi operating pres-

sure. and a pumped-off well, Eqs. 22, 33, and 36 lead to

(P/E),,,, =3,500/0.433/l,, =8.000/L,,, . . . . . . ..(54)

where L,, =net lift, ft.

Eq. 54 is useful in initial selection of an appropriate

PIE ratio in installation design. The actual final determi-

nation of the surface operating pressure will depend on

calculation of the actual gradients and losses in the sys-

tem and on the particular pump’s P/E ratio.

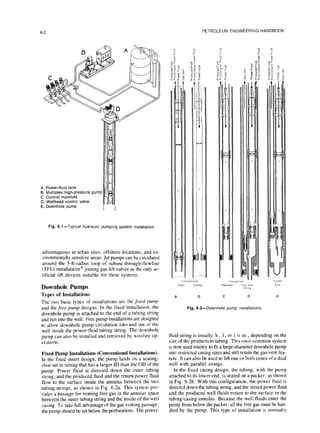

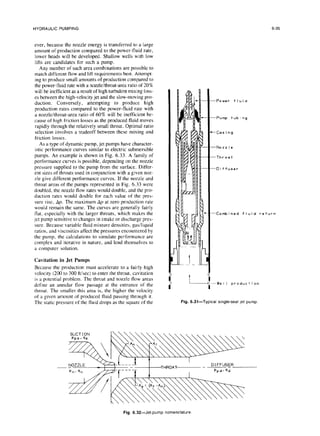

Equipment Selection and Performance Calculations

Equipment selection involves matching the characteris-

tics of hydraulic pumping systems to the parameters of

a particular well or group of wells. A worksheet and sum-

mary of equations are given in Table 6.7.

Once a downhole unit has been selected and its power-

fluid pressure and rate determined. an appropriate power

supply pump must be matched to it. The section on sur-

face equipment and pumps provides a detailed descrip-

tion of the types of pumps used for powering hydraulic

pumping systems. Specifications for some of the pumps

typically used can be found in Tables 6. I through 6.4

(Figs. 6.15 through 6.18).

A troubleshooting guide is provided in Tables 6.8

through 6. IO.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/hydraulicpumping-220105163948/85/Hydraulic-pumping-27-320.jpg)

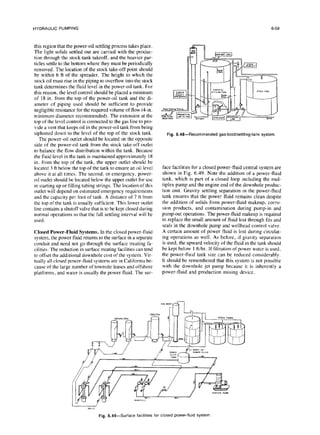

![HYDRAULIC PUMPING 6-29

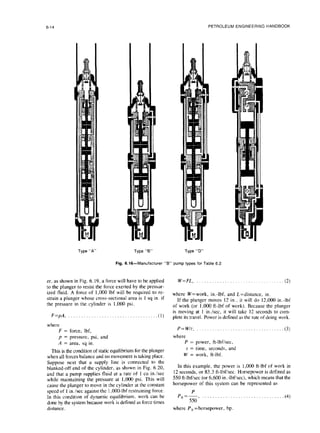

TABLE 6.7-WORKSHEET AND SUMMARY OF EQUATIONS FOR RECIPROCATING PUMPS

Well Identification

Example Problem 3

Vertical

setting

depth, ft 9,000

Tubing length,ft 9000

Tubing ID,in. 2.441

Tubrng OD, In. 2.875

Return ID, in. 4.892

Wellhead pressure,psi 100

Gas specific

gravity 0.75

011gravity,

“API 40

Power fluid

specific

gravity 0.82

Produced 011specific

gravtty 0.82

Water specific

gravity

Power fluid

gradient,

psiift

Produced oilgradient,psilft

Water gradient,psilft

Oilviscosity,

cSt

Water viscosity,

cSt

GOR, scflbbl

Water cut,%

Surface temperature, OF

Bottomhole temperature, OF

1.03

0.357

0.357

0.446

2

0.485

100

70

100

200

Expected net lift,

ft 7,800 Vented? Yes- No2

Desired production,B/D 250

Pump intakepressure at above rate,psi 500

Installation:

Casing i/ Parallel

_

OPF r, CPF

Step 1 -(P/O max

=8,000/L, = 1.03 (Eq. 54)

Step a--Maximum pump efficiency

Eprmax,

(Fig.6.27)

97

% (Vented)

% (Unvented)

Step 3-Minimum recommended pump displacement (Eq. 31):

qp =9,/; ~Epmax, xEp~,nt,

= 250/(0.8x0.97 x 0.85)= 379 B/D

max

Step 4-Select pump from Tables 6.1 through 6.4 with P/E lessthan or equal to value from Step 1 and a maximum rated

pump displacement equal to or greaterthan the value from Step 3

Pump designation:

Manufacturer B Type A 2% x 11/4-11/4

in.

PIE 1.oo

Rated displacement, B/D 492

Pump, BIDlstrokeslmin 4.92

Engine, BIDlstrokeslmin 5.02

Maximum rated speed, strokes/min 100

Step S-Pump speed:

N= qsW,~,,xl x Epc,ntr)l2WO.97xO.W

q,lN,,x =

= 61.6 strokes/min

4921100

Step B-Calculate power-fluid

rate(assume 90% engine efficiency,

E,)

qpf= N(q,/N,,,)/E, = 61.6(502/100)/0.90

= 344 B/D

Step 7-Return fluid

rateand properties-OPF system

a. Totalfluid

rate: power fluid

rate,

qp, = 344 BID

+ productronrate,9r = 250 BID

= totalrate,

qd = 594 BID

b.Water cut:

Water power fluid

(Eq. 44)

WC, = (9Pf+ W,q,)J9, =

Oil power fluid

(Eq. 45)

wcd=wcq,/q,=07x250/594=o.29

c. Vscosity (Eq.42)

v,,,

=(I - Wcd)vo + Wcdvw =(I -0.29)2+0.29x0.485= 1.56 cSt

d. Suction gradient(Eq. 40)

gs=g~(l-W,)+g,W,=0.357(1-0.7)+0.446x0.7=0.419psl/fi

e. Return gradient(Eq 41)

gd = [(9,(

xg,,) +(9s xg,)]/q, =[(344x 0.357)+(250 x0.419)1/594=0.383 psrlft

f. Gas/liquidratro

(Eq. 47)

F,, =q,(l - W,)R/q,=250(1 -0.7)100/594=12.6 scilbbl

Note: For vented installations,

use solutionGOR (Frg.6.27)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/hydraulicpumping-220105163948/85/Hydraulic-pumping-28-320.jpg)

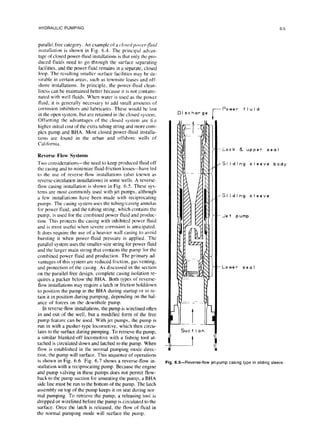

![6-30 PETROLEUM ENGINEERING HANDBOOK

TABLE 6.7-WORKSHEET AND SUMMARY OF EQUATIONS FOR RECIPROCATING PUMPS (continued)

Step B-Return fluid

ratesand properties-closed power-fluid

systems. Because the power fluid

and produced fluid

are kept

separate,the power returnconduit carriesthe flow ratefrom Step 6, with power-fluid

gradientand viscosity.

The production

returnconduit carriesthe desired production ratewith productiongradient,

water cut,viscosity,

and GOR.

a. Power-fluid

returnrate BID

b. Production returnrate BID

Step g--Return friction:

Ifa gas lift

chart or vertical

multiphase flowinggradientcorrelation

(see Chap. 5) isused forreturn

flow calculations,

itwill

already includefriction

values and the flowline

backpressure. Use of gas lift

chartsor correlations

is

suggested if

the gas/liquid

ratio

from Step 7 isgreaterthan IO.The value from such a correlation

can be used directly

in Step

llc withoutcalculating

friction

values. Ifa gas-lift

chart or vertical

flow correlation

isnot used, then with the values from Steps

7 and 8, as appropriate,

determine the returnconduit friction(s)

from the chartsor equations inAppendix 6.

1.Open power-fluid

friction

pfd = psi.

2. Closed power-fluid

friction

a. power returnpter

=- psi.

b. production returnptd=- psi.

Step lo-Power-fluid friction:

With the power-fluid

ratefrom Step 6, use the appropriatechartsor equations in Appendix B to

determine the power-fluid

friction

loss.

Power fluid

friction

prpt= 4.4 psi.

Step 11-Return pressures:

a.Open power-fluid

system (Eq. 33)

Ppd=Pfd+i?dD+P,= psi.

b.Closed power-fluid

system (Eqs. 37 and 38)

1.P ed=Plet+!?~D+Pwhe=--- psi

2.P,d=P,+!7,D+P,= psi

c. Ifa vertical

multiphase flowinggradientcorrelation

ISused insteadof Eqs. 33, 37, or 38, then ppd =3,500 psi,

Step 12-Required engine pressure ppf:

a. Open power-fluid

system (Eq. 22)

p,,=ppd[l+(P/E)]-pps(P/E)=3,500[1+1]-500(1)=6,500psi.

b.Closed power-fluid

system (Eq. 21)

Ppf ‘Ped +Ppd(PIE)-Pp,(PIE)= psi

Step 13-Calculate pump friction

a. Rated pump displacement,qp =492 B/D

b. Rated engine displacement,qe = 502 B/D

c.Totaldisplacement,qtm = 994 B/D

d. “8” value (Table 6.5)= 0.000278

e. N/N,,, = 61.61100=0.616

f.f,=~/100+0.99=2/100+0.99=1.01 (Eq. 28)

g. Pump friction

(Eq. 29 or Fig.6.24)

pb =yF,(50)(7.1ee9” jNINmax

plr=0.82(1.01)(50)[7.1eoooo278~994~]06’6

= 164 psi.

Step 14-Required surface operatingpressure p, (Eq. 36):

pso =pp, +ptpf-gprD+pr, =6,500+4.4-0.357(9,000)+ 164=3:455 psi

Step 15-Required surface horsepower, assuming 90% surface efficiency

(Eq. 5):

P, =qp,xp,, x0.000017/E, =344x3,455x0.000017/0.9=22.4 hp.

Step 16-Summary:

Pump designation-Manufacturer B Type A 21/z

x 1X-1% in.

Pump speed, strokeslmin 61.6

Production rate,B/D 250

Power fluid

rate,B/D 344

Power fluid

pressure,psi 3,455

Surface horsepower 22.4

Step 17-Triplex options (from manufacturer specification

sheet,Tables 6.16 through 6.18):

Type

J-30 D-323-H

Plunger size,in. 1% 1‘/a

Revolutionslmin 450 300

Flow rateat revolutionslmin

(B/D) 400 399

Maximum pressure rating,

psi 3,590 4.000

Horseoower 26 26](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/hydraulicpumping-220105163948/85/Hydraulic-pumping-29-320.jpg)

![HYDRAULIC PUMPING 6-45

TABLE 6.15-WORKSHEET AND SUMMARY OF EQUATIONS FOR JET PUMPS (continued)

Step P-Discharge pressure (Eq. 31) ifF,, i 10

pld from Appendix B. Pfd =-

P/,d =/‘fd +SdD+Pwh Ppd =

Step 3-Use vertical

multiphase flow correlation

ifFg, > IO to determine ppd

ppd = 1,780

Step 4-Calculate pressure ratio

(Eq. 58)

Fpo =(ppd -P~~Y(P~ -P& F,, = 0.318

Step 5-Calculate mass flow ratio

(Eq. 64)

F ~~~[1+~~8(~~“]~~-~,1+~~~~~

mm = F m,D,=0.791

9,X9”

1,756

0.305

1.04

1,746

0.300

1.09

Step g--Use value of F,, in Fig.6.34 to findF,,D from farthest

curve to right

at thatvalue of F,,. Note value of F,,.

F,, = 0.25 0.25 0.25

F mKJg =1.04 1.06 1.10

Step 7-Compare Fmfog from Step 5 with FmfDs from Step 6. IfwithinV/o, go to Step 8. Ifnot,correctqs by Eq. 71.

qspew)= q,~o,,,FmrD,

‘Fnm5

then returnto Step 6.1.a

9 sinewi

= 657 670 676

Part C-Hardware and finalcalculations

Step l-Pick throatsizeclosestto

A, = F =0.0412 sq in. Actual throatarea = 0.0441

al? size= 9

Step 2-Cavitation limited

flow (Eq. 72)

A,-An

9,,=4s,xy-

cm

qsc = 1,037

Step 3-Hydraulic horsepower (Eq. 5)

P, =q* xp,, x0.000017

Step 4-Triplex power at 90% efficiency

P, =35

=39

A, =0.0103 p so= 2,500 qs= 676

A, = 0.0441 qn= 820 P ps= 1,000

I= = 0.235

aD P,= 39

Triplexoptions(from manufacturer specification

sheet,Tables 6.16 through 6.18)

Type

D-323-H J-60

Plunger size,in. 1% 1%

revlmin 400 400

Flow rateat revlmin,B/D 945 945

Maximum rating,

pressure psi 2,690 2,690

Horsepower 44.6 44.6

K-l00

1a/4

221

945

2,740

44.6](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/hydraulicpumping-220105163948/85/Hydraulic-pumping-44-320.jpg)

![HYDRAULIC PUMPING

6-69

The compressibility of gas is a function of three

variables-gas specific gravity. temperature. and pressure.

for turbulent tlow, where

Q =f(yK, T, p). . .(A-@

A gas compressibility equation programmed for the

computer relates these variables as follows:

i,=A+Bp,+(l-A)e-‘-H(p,/10)~, _. (A-9)

where

AP, =

p=

pip =

L=

9=

d=

yP=

f=

=

=

friction pressure drop, psi,

weighted average viscosity. up.

weighted average kinematic viscosity, cSt,

length of tubing. ft,

quantity of oil flowing, B/D.

ID of tubing, in.,

weighted average specific gravity,

weighted average friction factor

WwG)

0.0361 (~I~)".z'/(dv)O~l'.

A=-0.101-0.36T,+1.3868(T,-0.919)”5. (A-10)

Transition from laminar to turbulent flow occurs when

the Reynolds number (NR~) is greater than 1,200.

B=0.021+0.04275/(7--0.65).

r,=(T+460)/(175+307y,),

p,=p~~/(701-47y,).

C=p,(D+Ep,+Fpr4). .

D=0.6222-0.224T,.. . . . .

E=O.O657/(T,-0.86)-0.037,

~=0.32~l-19.53’r~-1)1, _.

and

...... (A-l 1)

...... (A- 12)

...... (A-13)

...... (A-14)

...... (A-15)

...... (A-16)

...... (A-17)

H=0.]22e]-ll.“‘TI-~“I , .,,,........,.... (A-18)

where

Pi- = reduced pressure, and

T, = reduced temperature.

Appendix B-Friction Relationships

Because hydraulic pumping systems require greater cir-

culating volumes of fluid than other artificial lift systems,

the proper determination of friction losses is important.

This subject is thoroughly covered by F.B. Brown and

C.J. Coberly38 and includes the effect of viscosity gra-

dients, laminar to turbulent transitions, proper equivalent

diameters for annulus passages, and tubing eccentricity

in casing/tubing annular flow passages. Their results are

summarized in the following equations.

Circular Sections-Tubing

~=0.01191~. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . ..(B-1)

where

v = velocity, ftisec,

q = quantity of oil flowing, B/D, and

d = diameter of tubing, in.

Ap/=7.95x10-6$ . . . . . . .(B-2)

for laminar flow and

Ap~=N46&~$ . . ..t...... (B-3)

G-4)

Annular Sections-Flow Between Tubing and Casing

Laminar flow:

~=0.01191

9

d,2-d22

and

APT=

(d, -d2)2(dl’ -dzz)(1+l.5e’)’ “’

(B-6)

where

Ap, = friction pressure drop, psi,

p = weighted average viscosity, cp.

L = length of annulus, ft,

q = flow, B/D.

d, = ID of outer tube, in.,

dz = OD of inner tube, in.,

e = eccentricity of tubes=2d3/(d I -d?), and

d3 = distance inner tube is off center, in.

Turbulent Flow:

Ap’.f

=

(d, -d*)(d, 2-dz2)2

where

Appt.=

GE

L=

yQ=

friction pressure drop, psi,

flow, B/D,

length of annulus, ft,

weighted average specific gravity

(water= 1.O),

dl = ID of outer tube, in.,

dz = OD of inner tube, in.,

d3 = OD of coupling (inner tube), in..

e= eccentricity=(d, -d3)/(d1 -d2),

J‘= @(dvplp) =0.0361(Flp)“~2’ /(dv)“,2’, and

dP = weighted average kinematic viscosity, cSt.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . (B-7)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/hydraulicpumping-220105163948/85/Hydraulic-pumping-68-320.jpg)