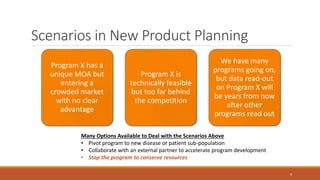

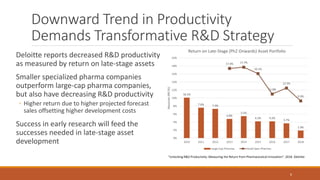

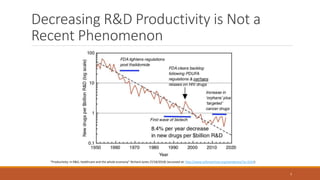

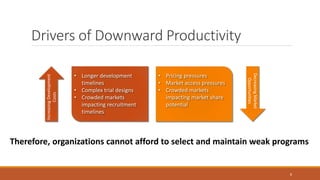

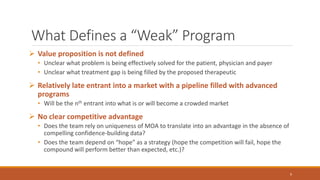

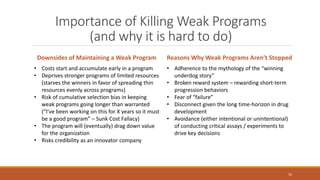

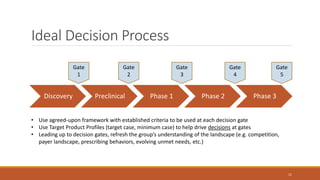

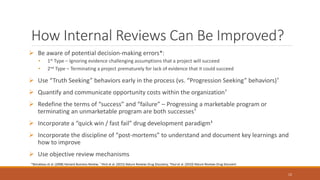

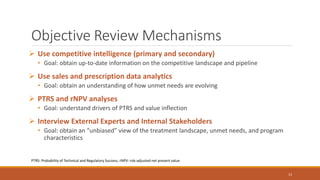

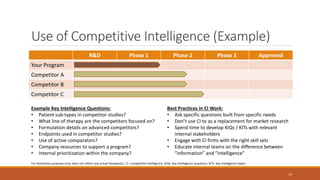

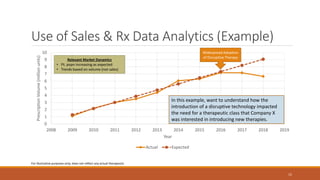

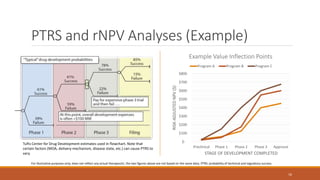

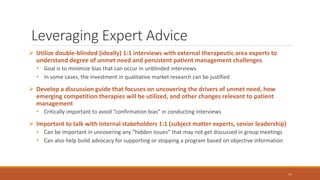

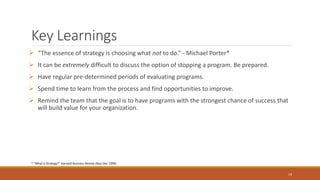

The document discusses effective strategies for terminating weak programs in pharmaceutical R&D to enhance productivity amidst declining trends. It highlights the importance of using objective review mechanisms, such as competitive intelligence and data analytics, to inform decision-making and evaluate the viability of programs. Additionally, it emphasizes the necessity of shifting corporate culture to accept program termination as a strategic success rather than a failure.