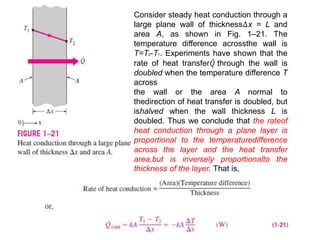

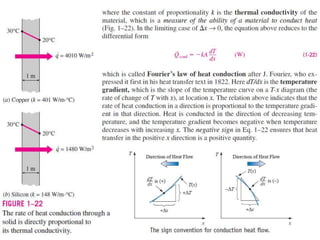

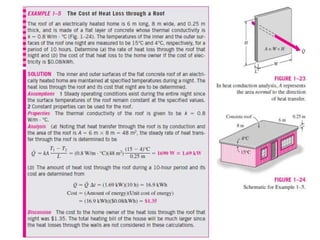

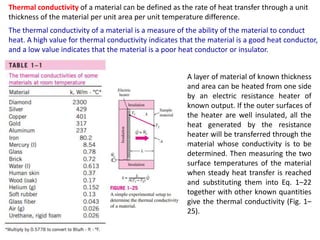

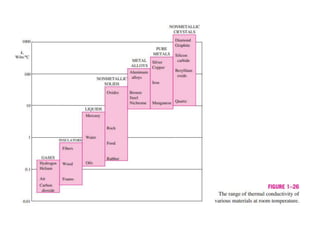

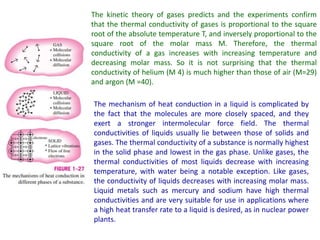

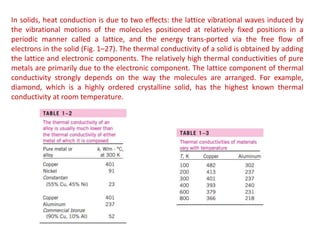

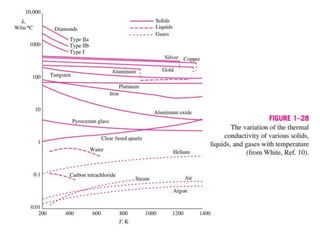

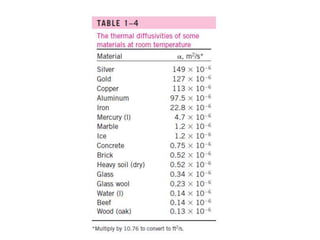

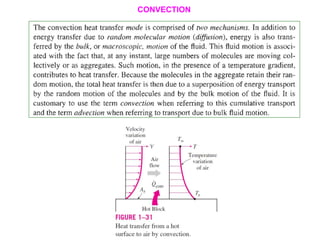

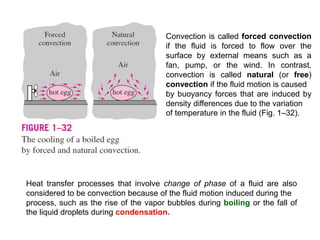

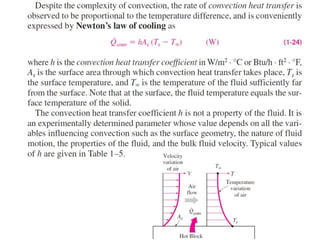

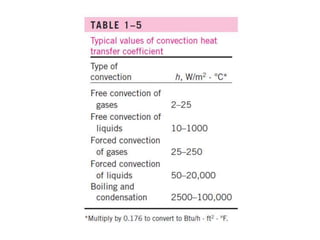

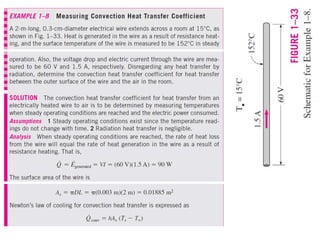

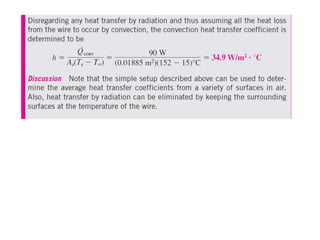

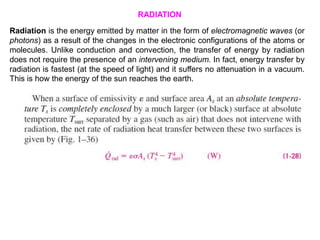

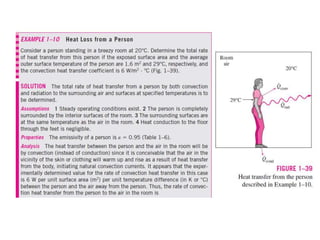

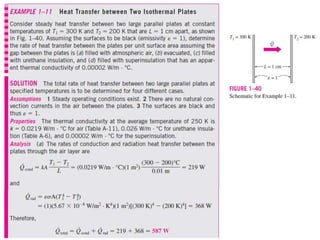

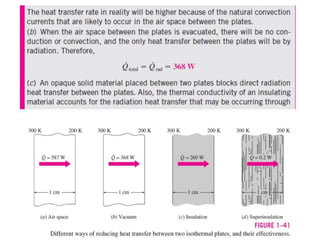

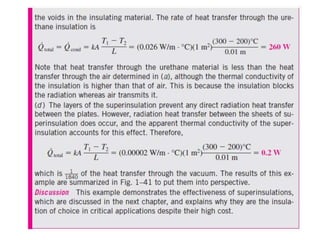

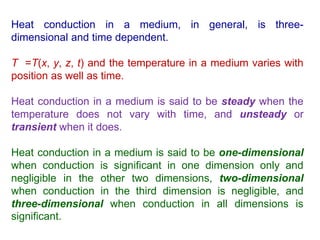

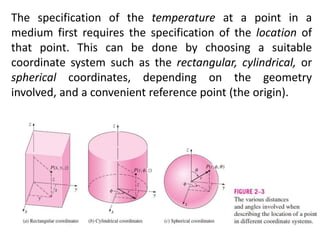

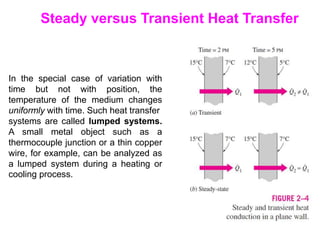

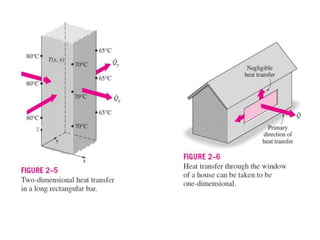

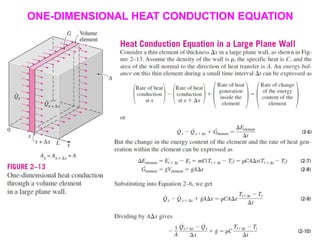

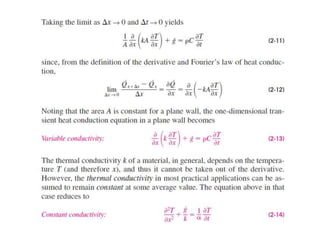

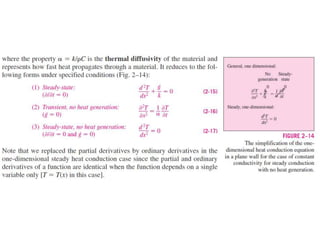

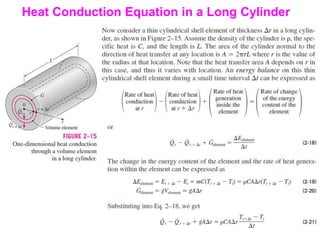

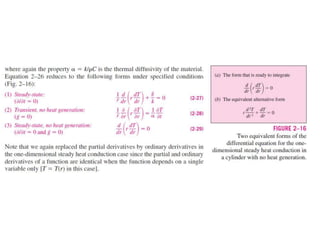

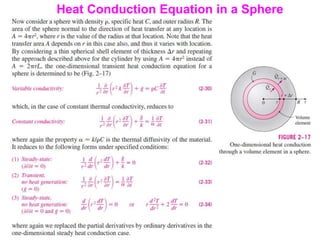

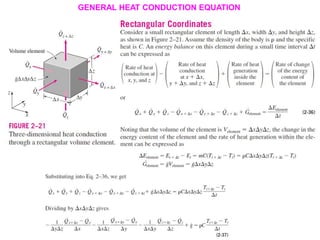

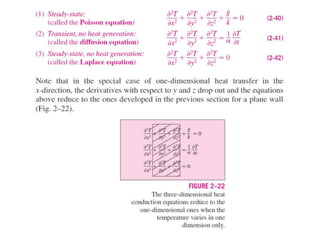

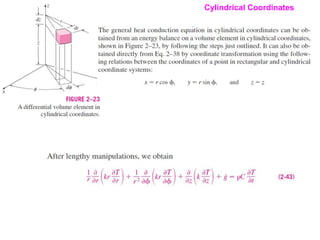

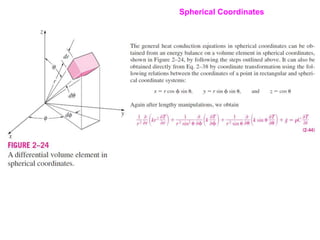

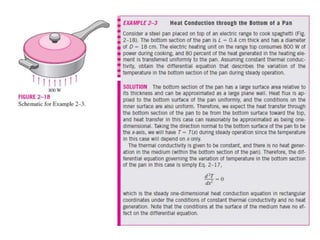

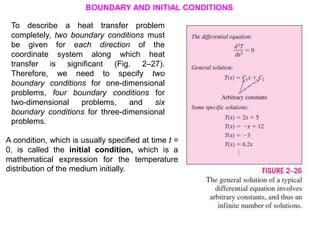

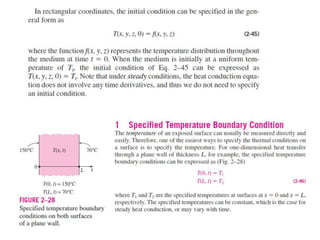

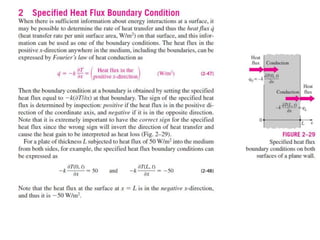

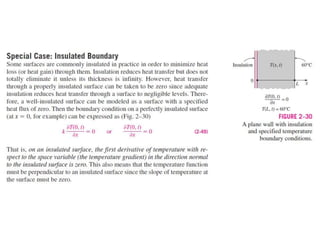

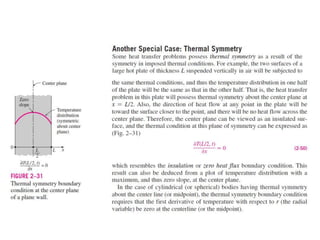

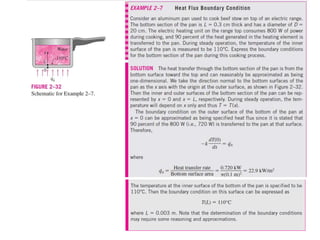

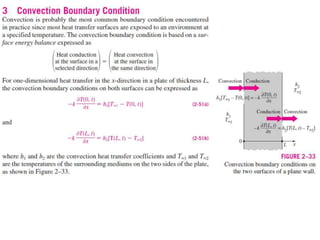

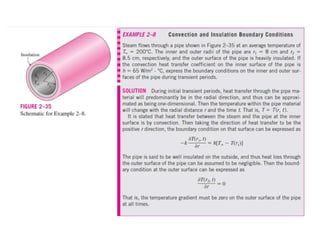

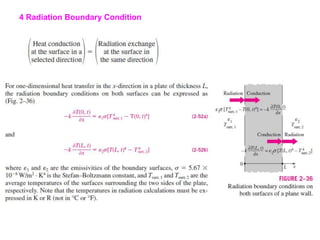

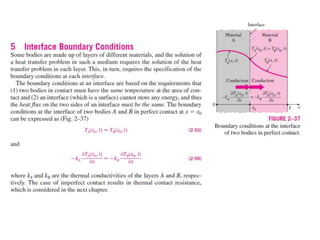

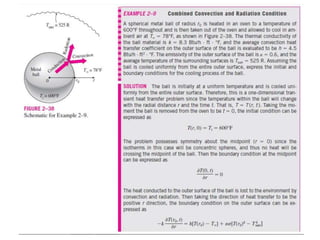

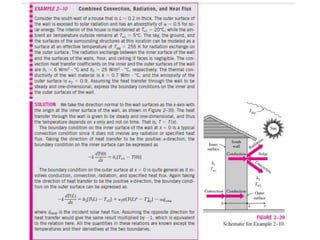

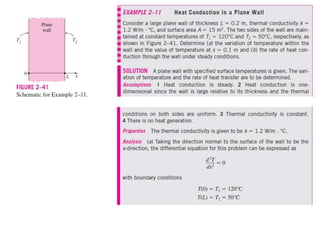

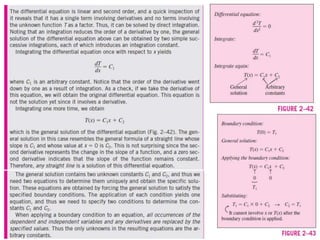

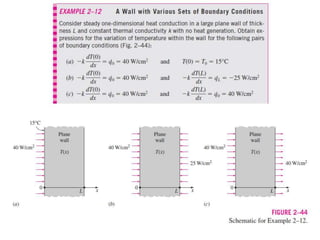

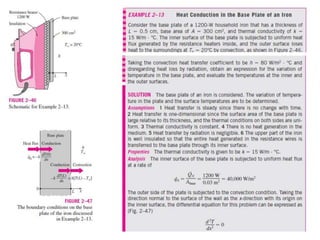

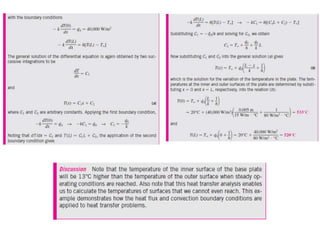

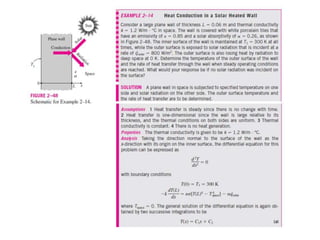

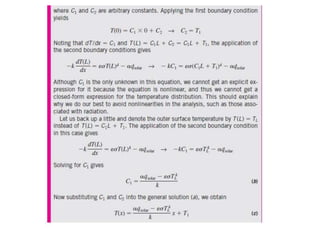

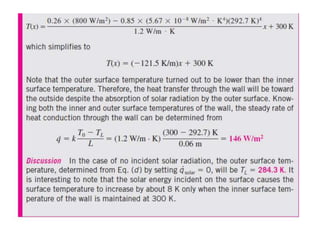

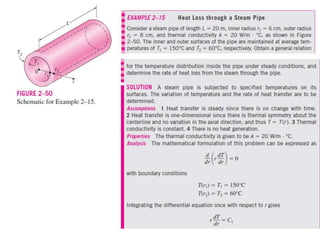

This document discusses different heat transfer mechanisms including conduction, convection, and radiation. Conduction involves the transfer of energy between particles through interactions at the molecular level in solids, liquids, and gases. Convection involves the transfer of heat by the motion of fluids and can be natural or forced. Radiation involves the emission of electromagnetic waves and does not require a medium to transfer heat. The document also discusses thermal conductivity, diffusivity, boundary and initial conditions, and the heat conduction equation in different coordinate systems.