This document provides an introduction to heat transfer and discusses the three main modes of heat transfer: conduction, convection, and radiation.

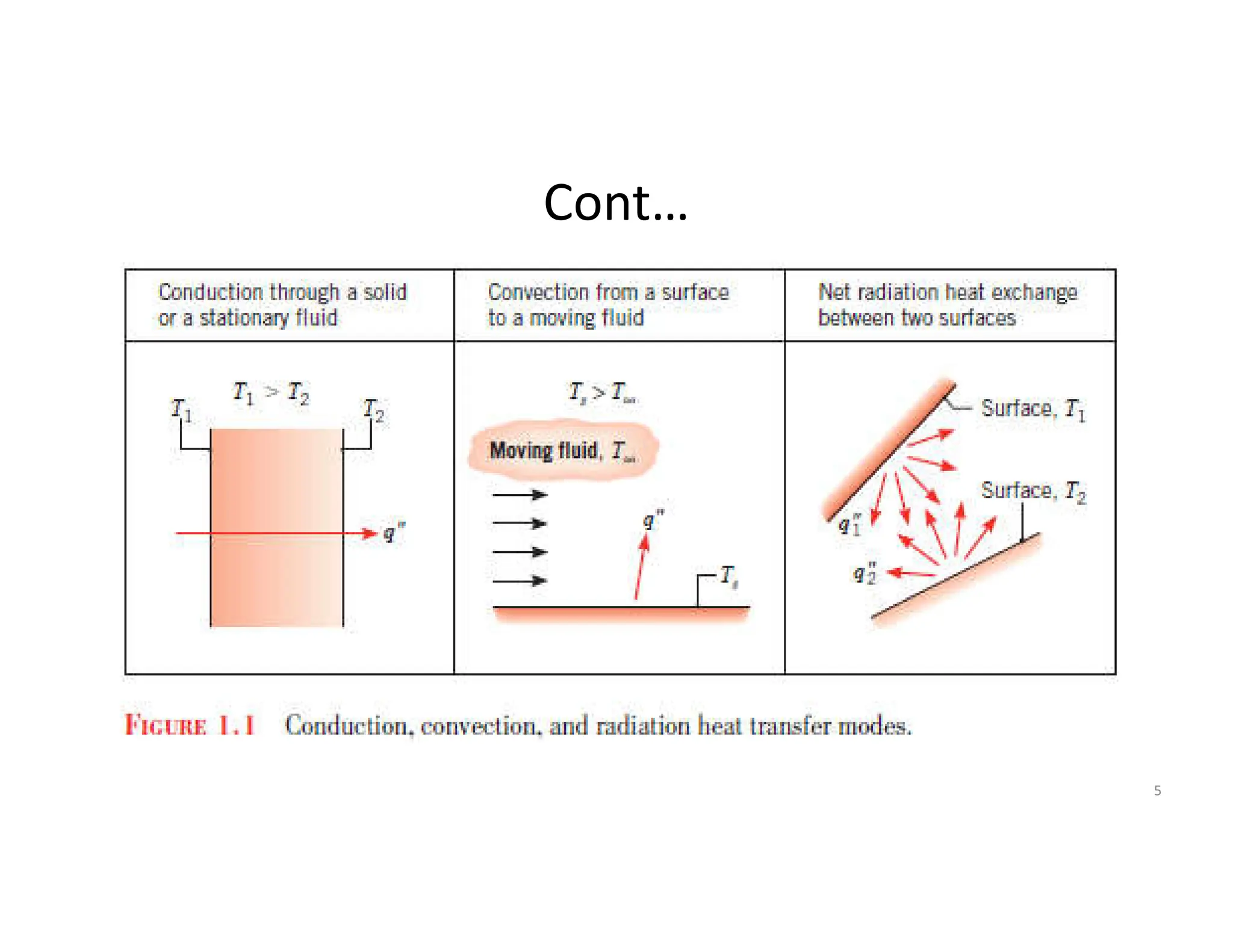

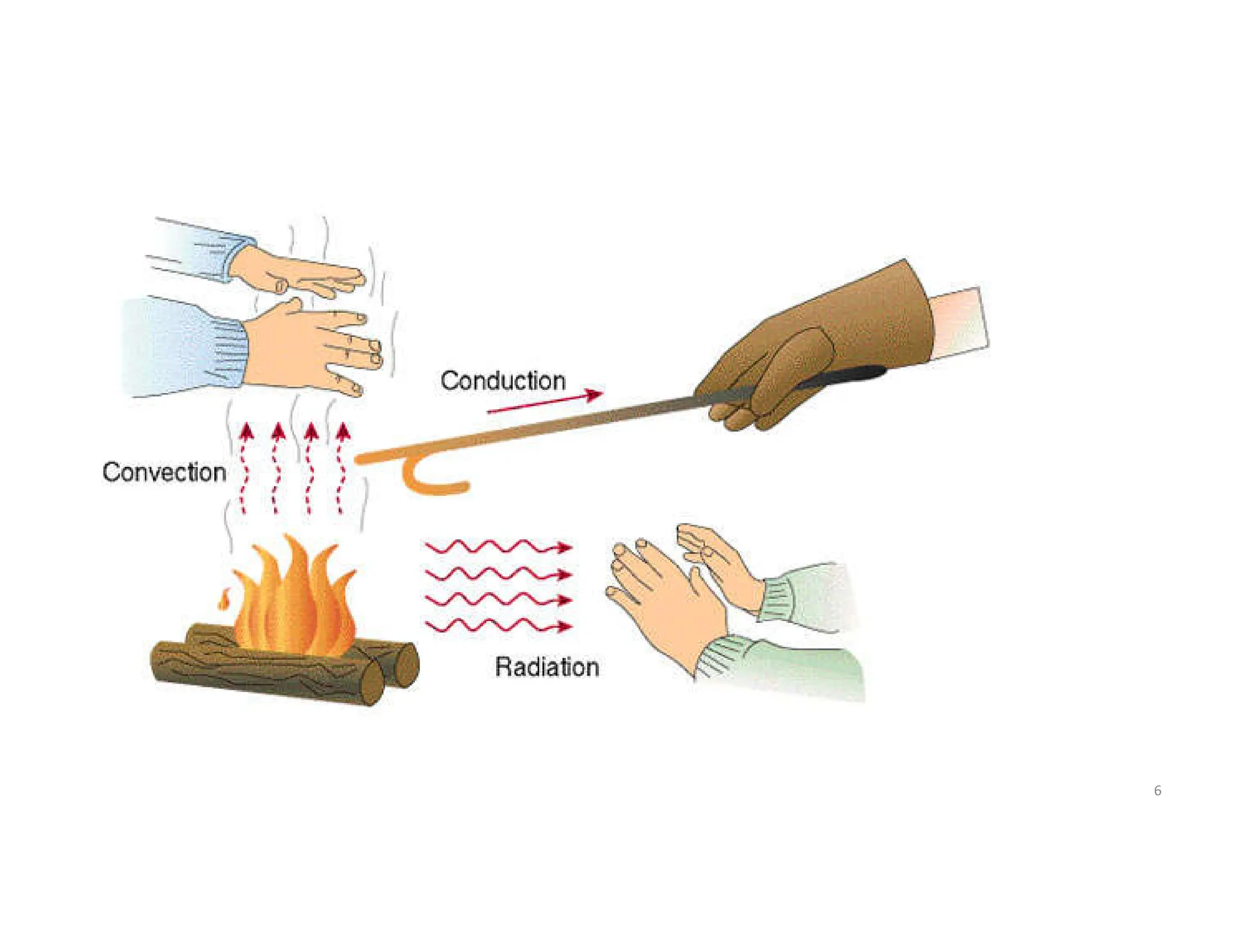

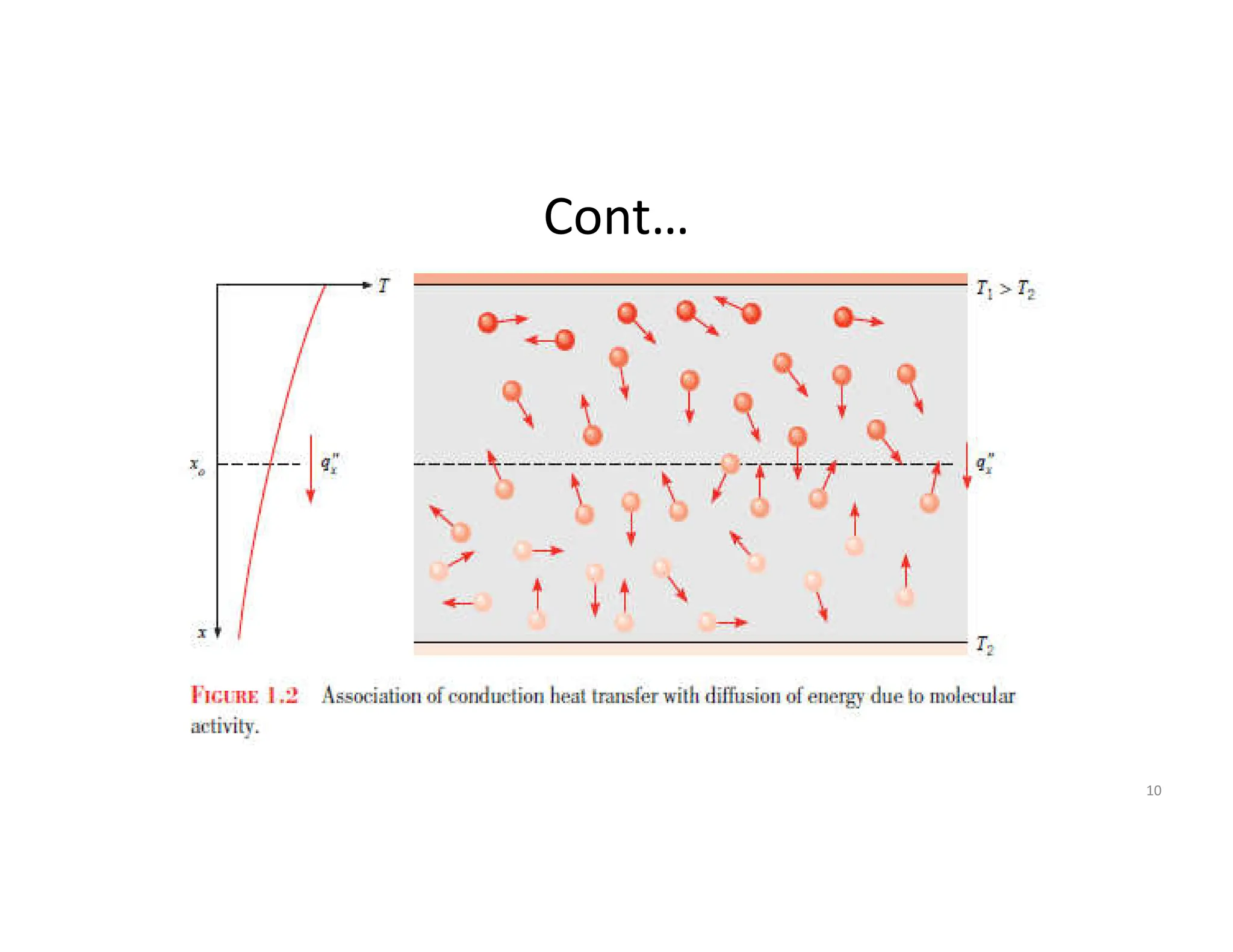

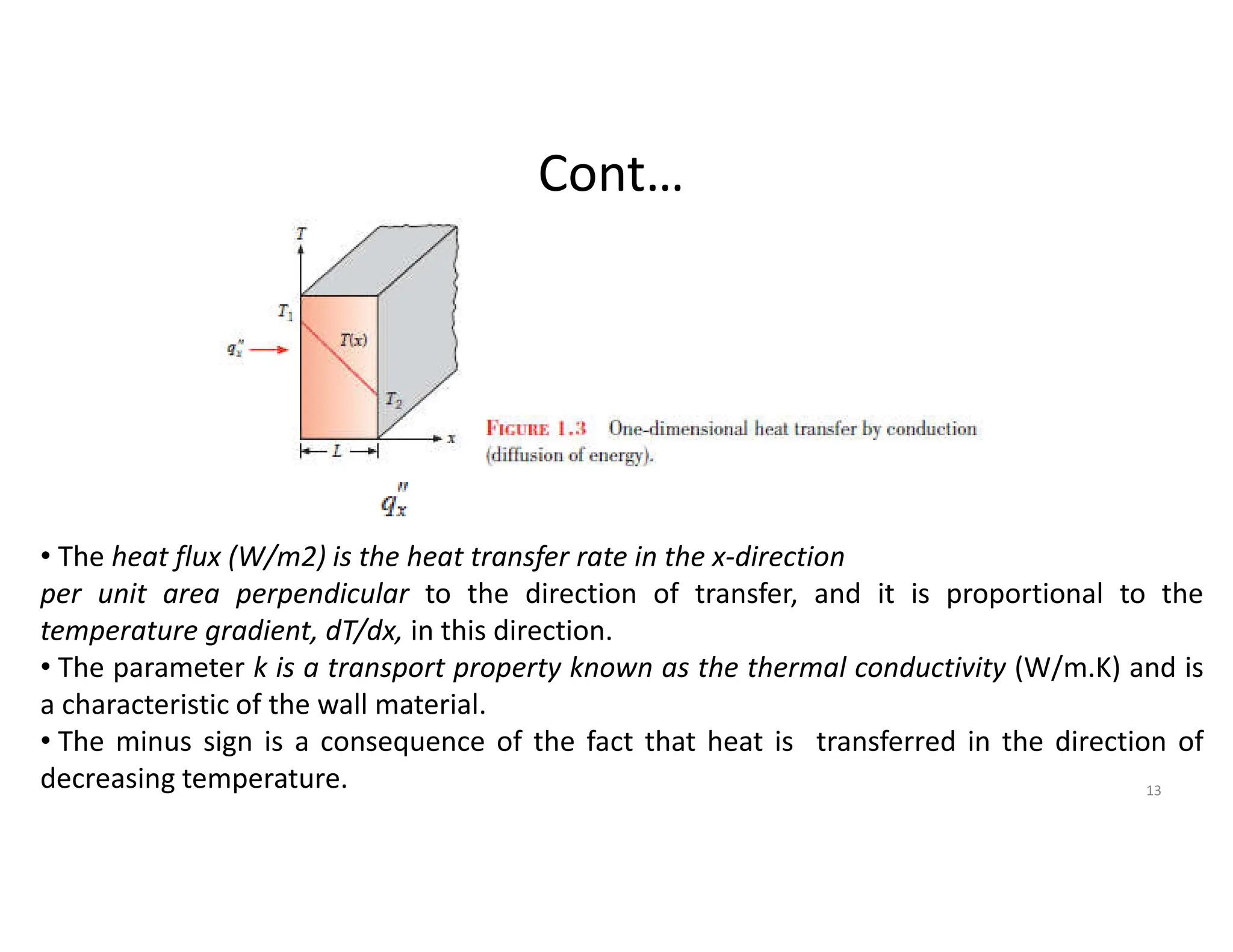

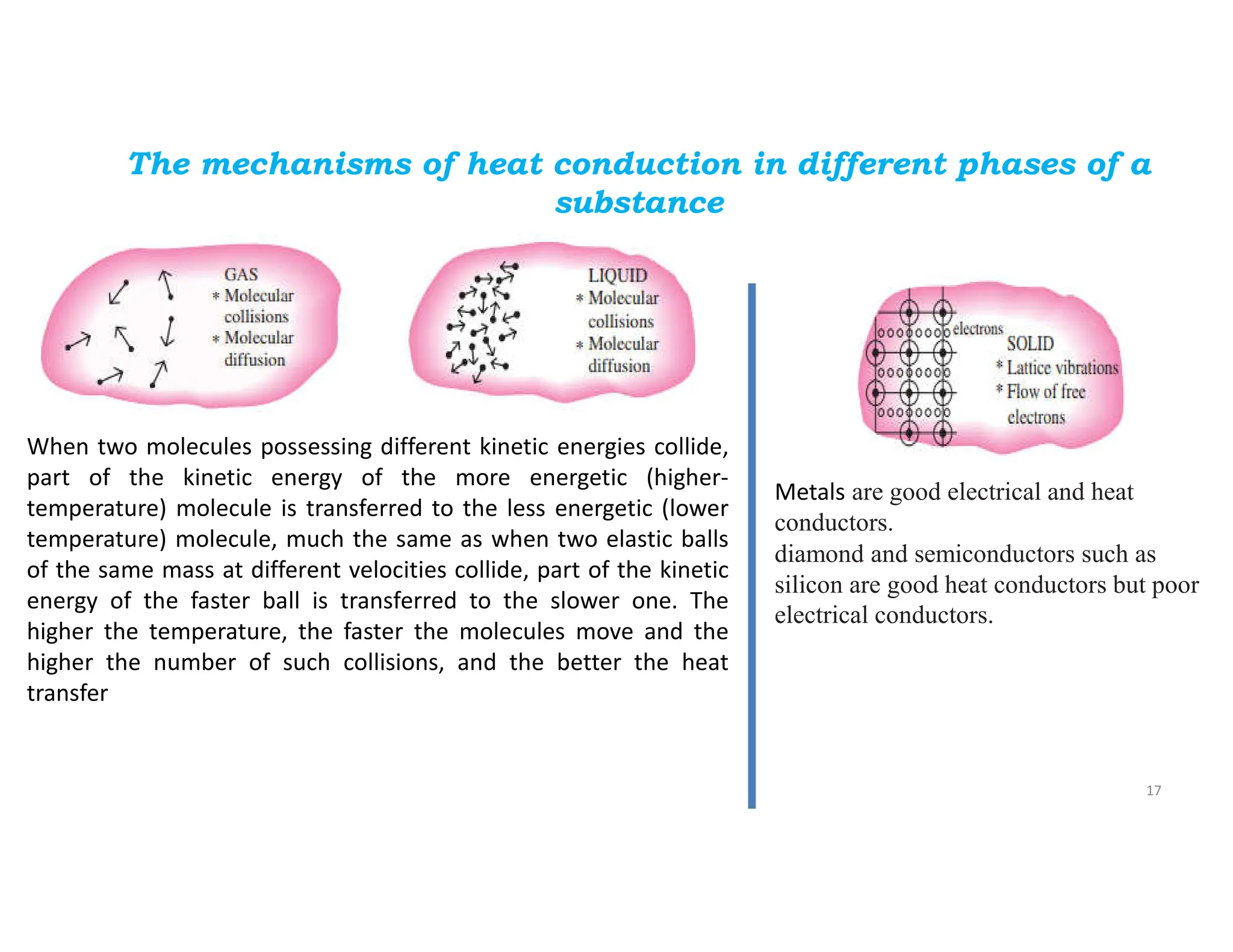

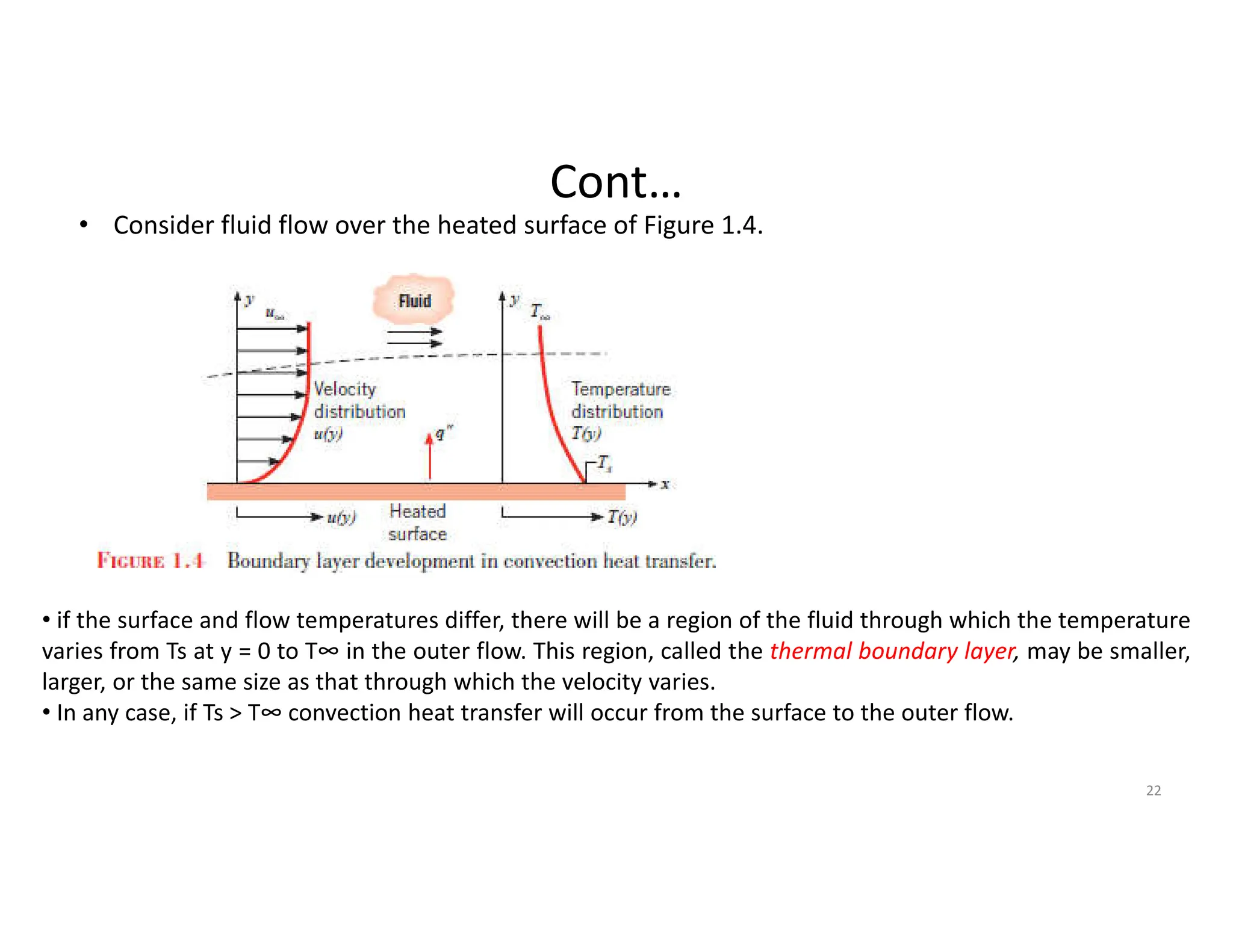

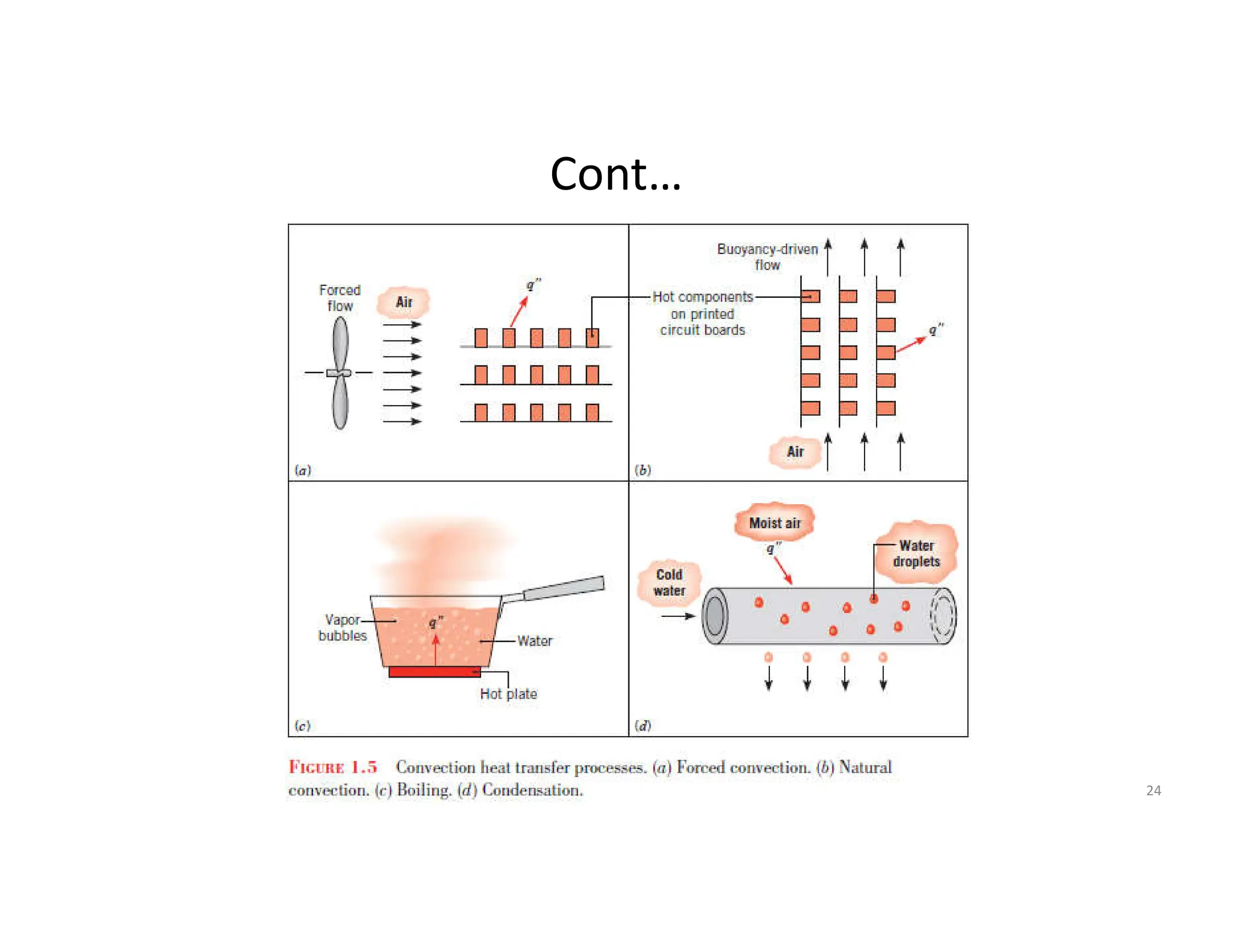

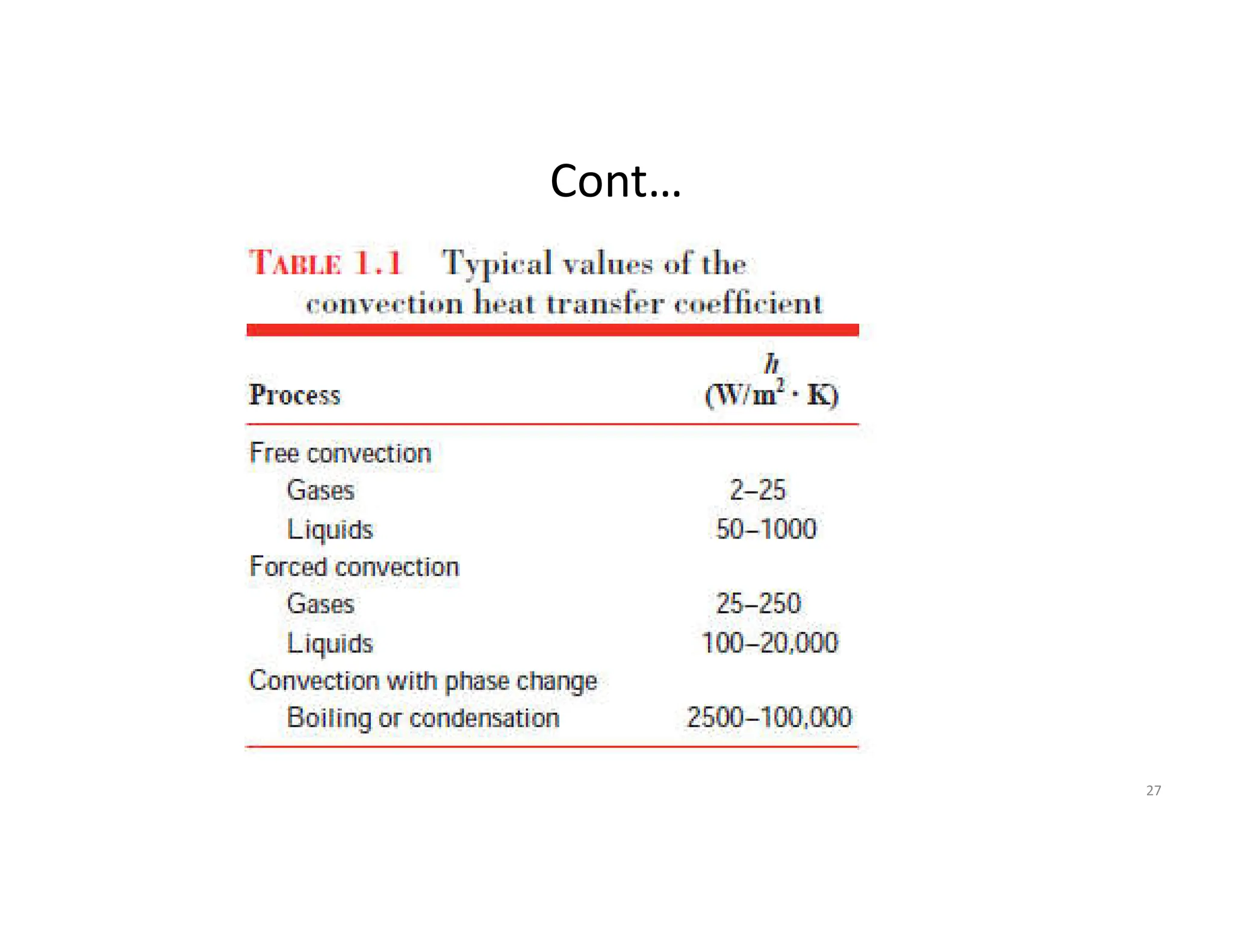

It defines heat transfer as the transfer of thermal energy due to a temperature difference and explains that conduction refers to heat transfer through a stationary solid or fluid medium, convection refers to heat transfer between a surface and moving fluid, and radiation refers to heat transfer via electromagnetic waves between surfaces.

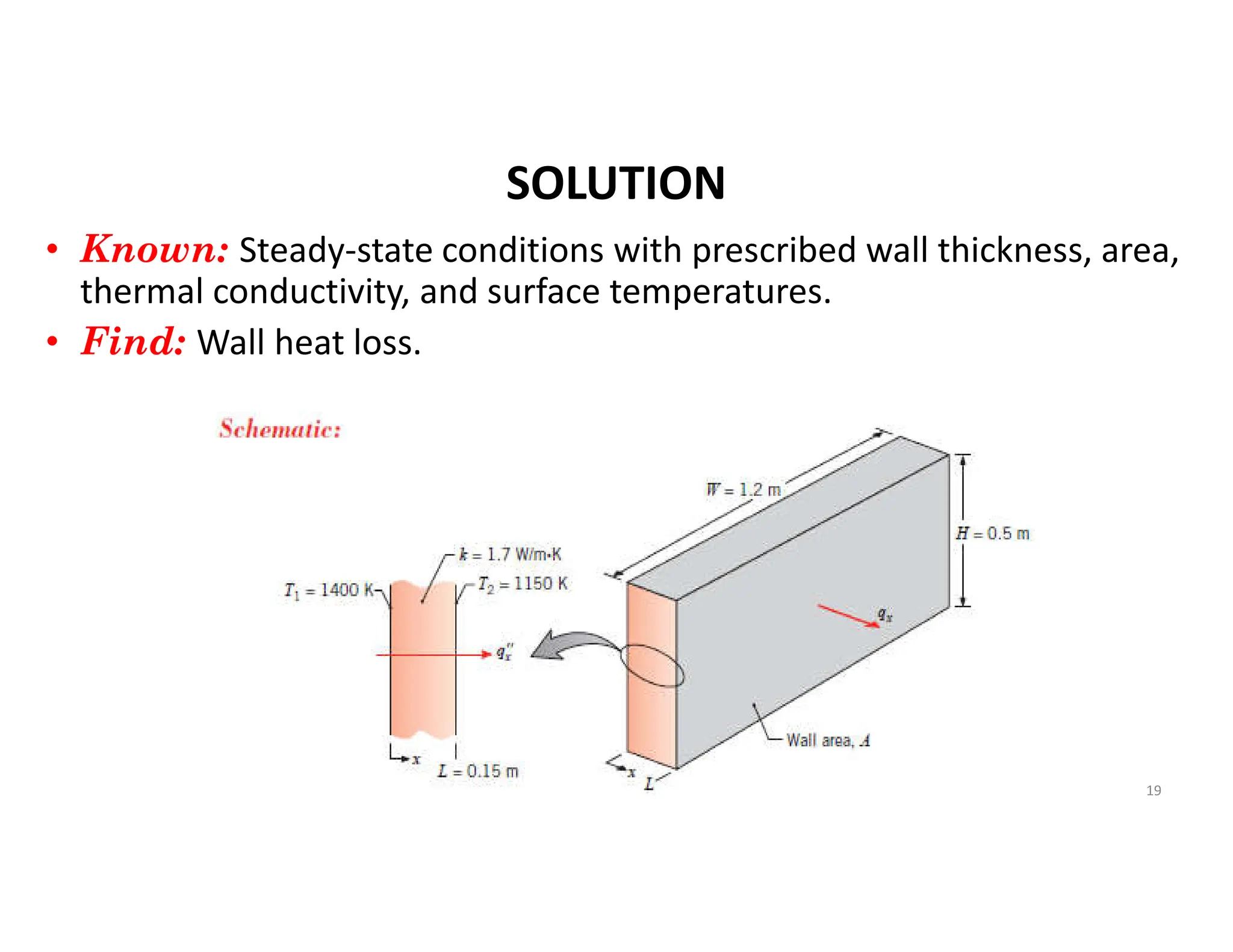

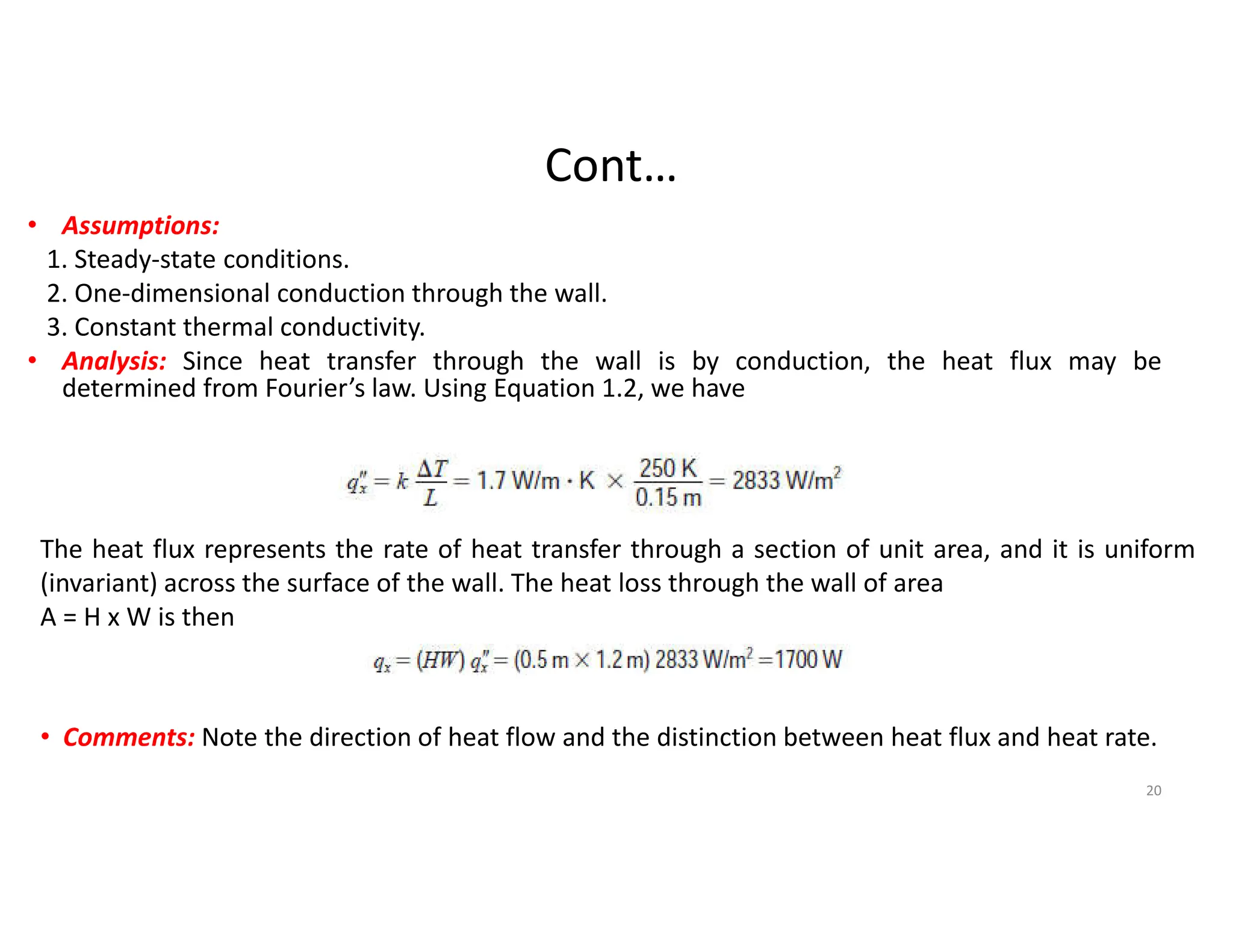

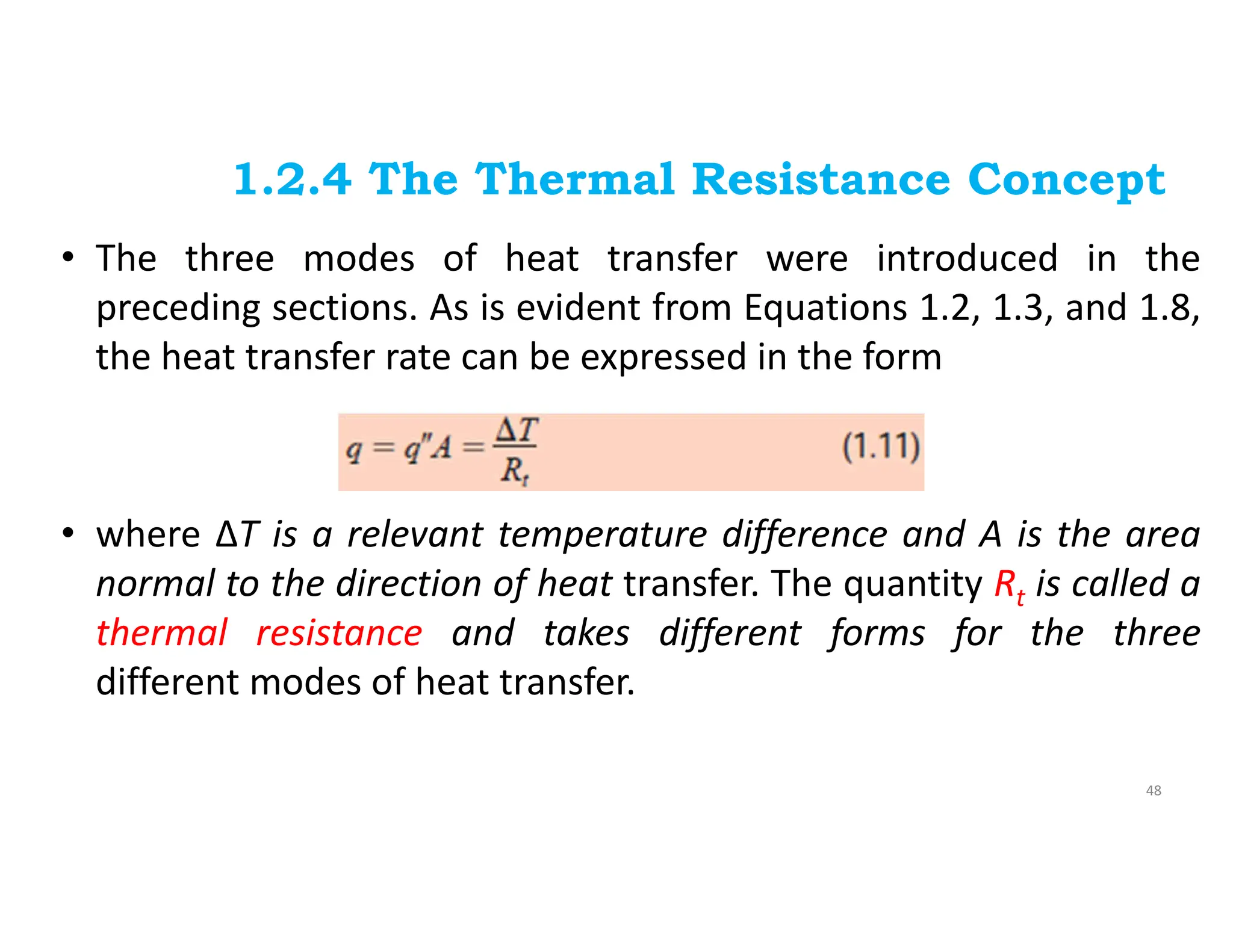

The document also presents the key equations for calculating heat transfer rates by each mode, including Fourier's law for conduction heat transfer rate and Newton's law of cooling for convective heat transfer rate.