This document presents the design and implementation of MySQL/JVM, a framework for embedding the Java Virtual Machine (JVM) runtime environment into the MySQL database server. This allows stored procedures and functions in MySQL to be written in the Java programming language, leveraging Java's robust libraries. Currently, MySQL only supports a basic procedural language for stored procedures. MySQL/JVM aims to address this limitation and enable functionality like XML validation and encryption that are difficult to implement in MySQL's native language.

![MySQL/JVM

A Framework for Enabling Java Language Stored Procedures in MySQL

Kevin Tankersley

Sacred Heart University

5151 Park Avenue

Fairfield, CT 06825

tankersleyk@sacredheart.edu

Abstract

Database procedural languages tend to be special-purpose lan-

guages, with constructs and libraries designed to support common

data access methods and flow control. To provide support for tasks

which cannot be solved with such basic data access functional-

ity, many database vendors embed the runtime environment of a

more general-purpose language in the database server, allowing

stored programs to be written in this external language. Such an

approach leverages the work that has already gone into design-

ing, implementing, and testing the runtime library of the external

language, while maintaining a low learning curve for advanced

functionality since many developers will already be fluent in this

external language. This paper presents the design, implementation,

and use of the MySQL/JVM system, a framework for embedding

the Java Virtual Machine runtime environment into the MySQL

database server to allow stored procedures and stored functions

in the MySQL database to be written in the Java programming

language.

Categories and Subject Descriptors H.2.3 [Database Manage-

ment]: Languages—Database (persistent) programming languages;

D.3.4 [Programming Languages]: Processors—Run-time environ-

ments; D.3.3 [Programming Languages]: Language Constructs

and Features—Data types and structures

General Terms Design, Languages, Security

Keywords MySQL, Java Native Interface, JNI, Stored Proce-

dures, SQL/JRT, ISO/IEC 9075-13

1. Introduction

Most relational database systems provide a procedural language,

which allows stored procedures to be hosted in the database to en-

capsulate common business logic, and allows user defined stored

functions to be created to calculate common metrics. The nature

of these languages and the robustness of the library of functions

available to them can vary widely from one vendor to another. For

example, MySQL includes a procedural language which offers ba-

sic control flow and has a fairly small library, Microsoft SQL Server

Permission to make digital or hard copies of all or part of this work for personal or

classroom use is granted without fee provided that copies are not made or distributed

for profit or commercial advantage and that copies bear this notice and the full citation

on the first page. To copy otherwise, to republish, to post on servers or to redistribute

to lists, requires prior specific permission and/or a fee.

offers control flow and basic exception handling with a larger li-

brary, and Oracle includes an object-oriented language with a fairly

robust library.

Given that the majority of the procedures hosted inside a

database system will be primarily intended to execute basic al-

gorithms over data sets and cursors, most of the functionality that

developers will need is present even in the least feature-rich stored

procedure languages. There are tasks, however, for which features

typically found in the libraries of more general purpose languages

may be needed. For example, processing and transmitting XML

documents has become a more common task in many databases

as XML standards have become widely accepted for data transfer.

Security policies for sensitive data may require custom encryption

routines and processes. Access to the file system, or to network

sockets, may be needed to acquire or export data. The degree of

support for these tasks is generally low in most database procedu-

ral languages.

To solve such problems, several database vendors allow stored

procedures to be written in a general purpose programming lan-

guage (in addition to the database native procedural language) in

order to expose the libraries provided by that language to devel-

opers. For example, the Oracle database allows stored procedures

to be written in the Java language, and Microsoft’s SQL Server

allows stored procedures to be written in any of the .NET lan-

guages. Further, all versions of the standard definition of the SQL

language since SQL:2003 [1] have consisted of 14 parts, one of

which (SQL/JRT [2], [5]) is dedicated entirely to defining the be-

havior of Java language stored procedures within a database server.

Currently, however, the MySQL database does not provide support

for Java language stored procedures.

This paper will present the MySQL/JVM system, a project

which integrates the Java Virtual Machine runtime environment

into the MySQL database server process to allow stored procedures

to be written in the Java language. The balance of this section will

present the features and characteristics of stored procedures in the

MySQL database. Section 2 will present the scope of the project,

and Section 3 will discuss the high level design. In section 4, lower

level design issues and noteworthy highlights of the implementa-

tion will be presented.

1.1 Stored Procedures, Functions, and Triggers

Relational databases are ubiquitous in application architecture.

Most of the major information systems used by a typical orga-

nization rely on a relational database server for their data storage

and retrieval needs. The role of the database as the originator of](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/1098c2f3-e28c-4b9d-a1b5-fc236967b210-160513172820/75/Graduate-Project-Summary-1-2048.jpg)

![data and the final destination of data makes it a good candidate to

assume data access control functionality. The centralization of the

database and the use of network protocols for data transfer also

makes it a potential performance bottleneck. The result has been

a migration of some program logic out of the applications making

use of the database and into the database itself, in the form of stored

procedures.

The term stored procedures will be used here to mean subrou-

tines which are stored in a location accessible to a database server

process and which the process may execute in response to an event

or on behalf of a client. Some distinction is typically made between

stored procedures and stored functions (or user-defined functions),

namely that stored functions can return a value to the caller. Further

distinction can be made between stored procedures and triggers on

the basis that triggers are not called explicity by a client but are in-

stead executed on the occurrence of some predefined event. When

such distinctions are important in the following sections, they will

be mentioned explicity; Otherwise the use of the term stored pro-

cedures throughout the rest of this paper will broadly refer to all of

these classes of stored code.

Migrating common business logic out of applications and into

stored procedures can bring several benefits. Stored procedures

may be able to implement logic containing multiple decision points

more efficiently than a client application, since a stored procedure

does not need to make each data request over the network. On many

systems, the statements in the procedure are precompiled, so that

executing a stored procedure will be faster than executing a block

of the same statements. Implementing stored procedures makes the

business logic they encapsulate reusable across applications. Stored

procedures can also be used to create fine-grained access control

policies.

1.2 Stored Procedures in the MySQL Database

MySQL is a relational database management system. Development

on the MySQL project began as early as 1994, and the features of

the server have grown steadily since. MySQL now supports most

of the SQL:1999 standard, and has become extremely popular, with

more than 100 million distributions to date. The MySQL server is

widely used as the underlying data store backing many web appli-

cations. The source code for the MySQL server is freely available

under the terms of the GNU General Public License.

Stored procedures were added to MySQL in its fifth version

in 2005. The syntax for creating and executing stored procedures

loosely adheres to the SQL:2003 Persistent Stored Module stan-

dard [3] (see [11] for full details concerning stored procedure syn-

tax and features). The stored procedure language provides flow

control via such statements as IF, LOOP, and WHILE; a BEGIN ...

END syntax for blocks; a DECLARE statement for variable declara-

tion and a SET statement for variable assignment; OPEN, CLOSE,

and FETCH statements for cursors; a RETURN statement for func-

tions; and a DECLARE ... HANDLER for exception handling. User

defined types, packages, and objects are not supported. The lan-

guage provides about 250 functions and operators for control flow,

string manipulation, mathematics, date and time manipulation, type

casting, XML processing, aggregation, spatial data manipulation,

binary data operations, encryption and compression.

1.3 Limitations of Stored Procedures in MySQL

The procedural statements and function libraries discussed in sec-

tion 1.2 are certainly sufficient for a large number of tasks related

to data processing, but they do not provide much support for more

advanced functionality. Below are several use cases that cannot be

easily achieved by using the existing stored procedure language of

MySQL. Each case could be implemented within individual ap-

plications instead of in the database, of course, but such a solu-

tion would lose all of the benefits discussed in section 1.1. When

databases do provide robust, general purpose libraries, the choice

of whether to implement common business logic in the database

or in each application that uses the data is an important design de-

cision. The following cases would be good candidates for stored

procedures, if MySQL had sufficient support to develop solutions

for them:

1. The database regularly receives and stores XML documents

which are supposed to adhere to a particular XML Schema.

The documents are generated independently by several source

systems, each implemented in different languages and using

different XML platforms. To detect and control errors, it would

be desirable for the database to ensure the validity of each

document and to verify that it does conform to the expected

schema.

2. The database needs to store sensitive information in an en-

crypted form. Symmetric encryption is deemed unsuitable due

to problems in properly protecting the shared encryption key.

A public key encryption protocol is desired to protect the most

sensitive data; Preferably one which does not have to be re-

implemented in each client application.

3. An organization is employing a service-oriented application ar-

chitecture, and valuable data services are available over the net-

work. It would be both costly and undesirable for the function-

ality made available by these services to be re-implemented in

the database. It would be ideal if a procedure could be written

to access such services whenever the database needs them.

2. Scope

Bringing Java language stored procedures to MySQL is a very

high-level goal. Both the Java runtime environment and the MySQL

database are complex systems, which can in fact already interact

independently over network protocols. Further, Java technology

is highly standardized, by way of the Java Community Process.

Expert groups consisting of representatives from multiple product

vendors draft technology specifications in the form of Java Speci-

fication Requests, which in turn become the standards to adhere to

when working with a Java technology area.

The SQL language is also governed by a defining standard (the

most recent version of which is defined by [4]). The standard con-

sists of the nine interrelated parts in Table 1, each of which is iden-

tified by a standard ID (e.g. ISO/IEC 9075-1:2008), a full name

(e.g. Information Technology–Database Language–SQL– Part 1:

Framework), and a short mnemonic identifier (e.g. SQL/Frame-

work).

Official claims of conformance to one of the nine parts of this

standard are verified by a conformance audit. No vendor currently

claims full official conformance to all nine parts of the standard,

and some vendors do not pursue official conformance at all, choos-

ing instead simply to design their products to comply with the stan-

dards as much as possible but to make exceptions or extensions as

needed. The features and behavior of the MySQL database server

comply closely with several of the nine parts of the SQL standard.

In particular, the stored procedure language used by MySQL is one

of the few vendor languages that closely conforms to the language

specified in the SQL/PSM substandard for defining stored routines.

It is noteworthy that part 13 (SQL/JRT) defines a standard for Java

stored procedures that builds on the syntax and standards defined in](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/1098c2f3-e28c-4b9d-a1b5-fc236967b210-160513172820/75/Graduate-Project-Summary-2-2048.jpg)

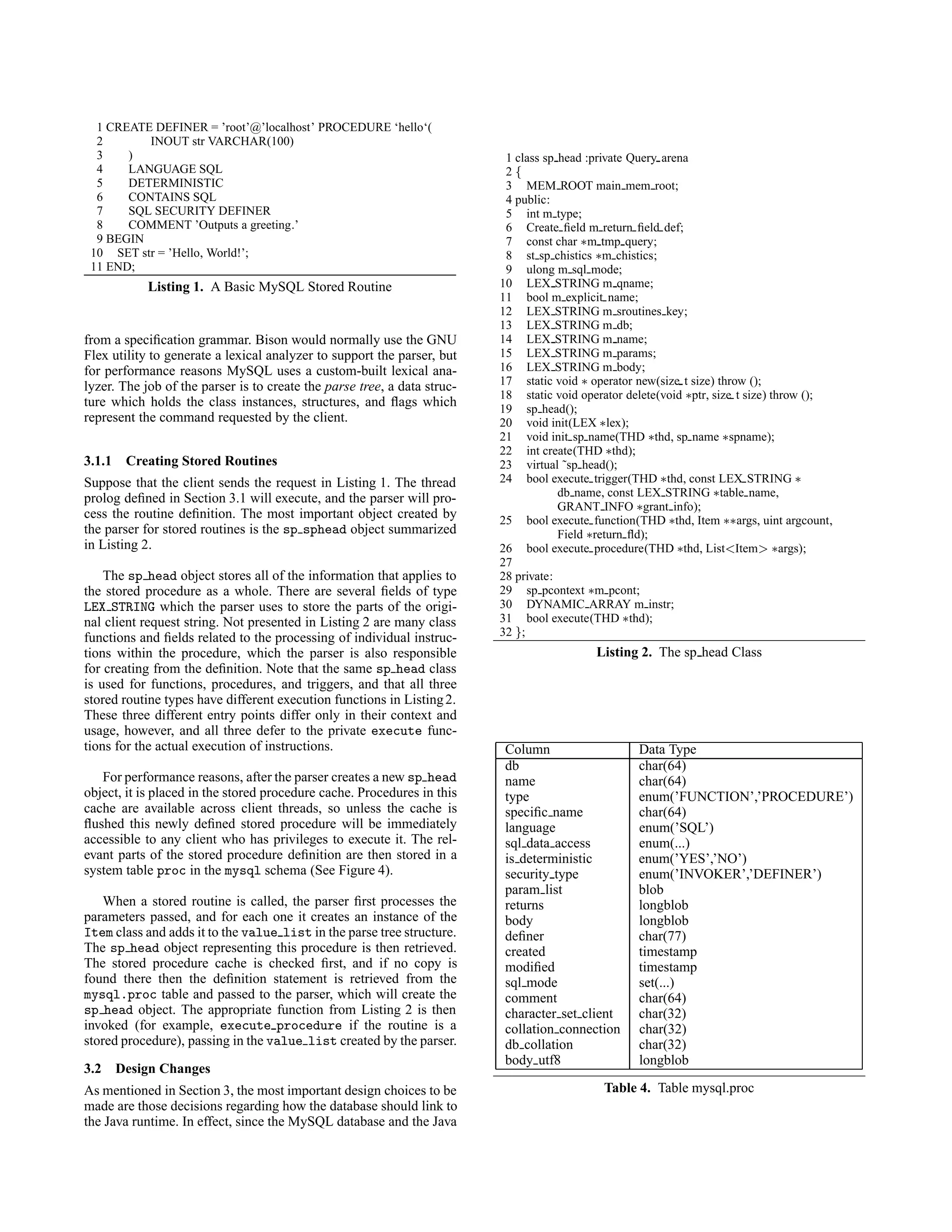

![ISO/IEC ID Name Mnemonic

9075-1:2008 Framework SQL/Framework

9075-2:2008 Foundation SQL/Foundation

9075-3:2008 Call-Level Interface SQL/CLI

9075-4:2008 Persistent Stored Modules SQL/PSM

9075-9:2008 Management of External Data SQL/MED

9075-10:2008 Object Language Bindings SQL/OLB

9075-11:2008 Information and Definition

Schemas

SQL/Schemata

9075-13:2008 SQL Routines and Types Us-

ing the Java TM Programming

Language

SQL/JRT

9075-14:2008 XML-Related Specifications SQL/XML

Table 1. ISO/IEC 9075:2008 Substandards

Feature Feature Name Compliance

1 J511 Commands In Scope

2 J521 JDBC data types Out of Scope

3 J531 Deployment No Compliance

4 J541 SERIALIZABLE Out of Scope

5 J551 SQLDATA Out of Scope

6 J561 JAR privileges Out of Scope

7 J571 NEW operator Out of Scope

8 J581 Output parameters In Scope

9 J591 Overloading Out of Scope

10 J601 SQL-Java paths No Compliance

11 J611 References Out of Scope

12 J621 External Java routines In Scope

13 J622 External Java types Out of Scope

14 J631 Java signatures In Scope

15 J641 Static fields Out of Scope

16 J651 Information Schema Out of Scope

17 J652 Usage tables Out of Scope

Table 2. SQL/JRT Feature Sets

SQL/PSM. Since the stored routine language in MySQL is already

in close compliance with SQL/PSM, defining what levels of con-

formance this project will have with the elements of the SQL/JRT

standard are the primary scope decisions to be made.

2.1 ISO Standard Compliance

The SQL/JRT ISO standard [4] is a large standard. In fact, it is large

enough that it groups the feature requirements it defines into sev-

enteen feature sets. Table 2 defines whether each of the seventeen

feature sets are in scope, out of scope, or will not be a conformance

target for this project. Features which are in scope for this project

will be implemented in close compliance to the SQL/JRT specifi-

cation. Features which are out of scope will not be implemented,

but the implementation will be structured such that they can be

added in the future. Features which are not compliance targets will

not be implemented, and it is unlikely that they could be added to

the system without a substantial redesign. The presence of such

features does not necessarily preclude a claim of conformance to

the specification, however. An official claim of conformance to

the specification requires, at a minimum, one of the features J621,

J541, or J551 together with one of the features J511 or J531.

The features can be even more broadly classified as those which

support the definition and execution of Java stored routines, those

which support the definition and execution of user defined Java

types, those which define the interaction between the database and

the Java runtime environment, and those which define the tables

and views which should be exposed as database metadata. The pri-

mary scope of this project is to integrate the Java Virtual Machine

into the database engine and to provide an API through which calls

can be made from the Java runtime to the database or vice-versa.

The project will comply closely with the feature sets in Table 2

which fall within that scope.

The SQL/JRT specification devotes roughly half of the features

it defines to defining and invoking Java routines, and devotes the

other half to defining and using Java language user-defined types.

Any feature relating to the creation of user-defined types with the

Java language is out of scope, and left for future development.

Since MySQL does not currently have any support for user-defined

types, even in the host language, such a change would be too large

of a task to complete within the timeframe of the project. Such a

type system could be added later, though, and could easily leverage

the framework which will be built to support routine calls.

For reasons discussed in Section 3, the subsystem for locating

Java classfiles will differ significantly from the recommendations in

SQL/JRT. As a result, the system will not comply with the features

in Table 2 relating to the deployment of Java classfiles and the

resolution of Java paths. Further, it would not be reasonable to bring

the system into compliance with these features without a major re-

write (possibly a total re-write). As mentioned above, this does not

mean that an official claim of compliance could not be made, since

a minimal claim of compliance can be made without either of the

features J531 or J601.

2.2 Other Scope Considerations

Within the features defined in Section 2.1, there are still a num-

ber of scope decisions to be made. The SQL/JRT standard defines

the features that a compliant database server must provide from a

fairly high level, but it does not provide many mandates concerning

the design details related to implementing those features. In partic-

ular, there are several subsystems which the Java runtime and the

MySQL database server have in common. Ideally, a seamless inte-

gration would fully integrate each such subsystem. Since there will

not be sufficient time to provide a full integration of each subsys-

tem, the remainder of this section will discuss the scoping decisions

for each major touch point between the database and the Java run-

time.

2.2.1 Access Control

Security in MySQL is managed in a fairly standard way through

a remote login process and access control lists. The access control

lists control access to resources such as tables, views, and stored

procedures. The access control allows actions such as CREATE,

DROP, SELECT, and EXECUTE against these resources, and these ac-

tions can either be explicitly allowed (GRANT) or denied (REVOKE).

(See [11] for a more complete listing of MySQL access control

commands).

Security in the Java runtime, however, is managed rather differ-

ently. The default security model for the Java runtime assigns per-

missions based on the notion of a CODESOURCE, which is primarily

a combination of a URL identifying where an archive originated

and possibly a cryptographic signature of the code. This policy

essentially allows local Java code to execute with access to the en-

tire runtime, but restricts the access of remotely downloaded code

such as Java Applets. This default policy is difficult to integrate

in a meaningful way with the user-driven access control policy of

MySQL. It should be noted that a custom security policy could be

written by system administrators, and there are Java Specifications

and APIs which allow user-driven access control to be enforced -](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/1098c2f3-e28c-4b9d-a1b5-fc236967b210-160513172820/75/Graduate-Project-Summary-3-2048.jpg)

![see [6] for more details on access control options in Java.

The Java runtime provides access to some very powerful re-

sources (e.g. network sockets and file operations), which is exactly

why it is useful as a language for stored routines. Some of these

might use significant memory or processor resources, however,

which can be a big problem in a database server which is typically

multi-user and performance-sensitive. Ultimately, the database ad-

ministrator is the individual responsible for ensuring that access

control is setup optimally. The database administrator should have

a simple way to control access to the various sensitive resources

in the Java runtime. Ideally this would come in the form of ex-

tending the GRANT and REVOKE actions to include Java resources

(e.g. ‘GRANT OPEN SOCKET TO USER1’ or ‘GRANT WRITE FILE

TO USER2’). The implementation differences between the Java se-

curity model and the MySQL security model currently make this

an unreasonable goal, although it is an interesting area for future

development.

2.2.2 Output

Several database vendors provide a channel across which basic

messages can be sent from a stored procedure. Microsoft SQL

Server, for example, provides a print statement, and the Oracle

database provides the dbms output.put line procedure. In some

cases, the client may even choose whether or not information re-

ceived through this channel will be processed, making it a useful

tool for diagnostics information or debugging information.

The MySQL database, however, does not provide such a chan-

nel. This is more than just a missing feature in the language - the

TCP protocol which the client and server use to communicate does

not even define any structure which could be used to pass such data

(see [10] for a description of the MySQL network protocol).

The scope of this project is certainly limited to the server pro-

cess itself. Even a small change to the communication protocol

would render all existing clients unable to connect to the server. As

such, no diagnostic channel will be created or assumed. The Java

runtime, however, frequently sends output to the user through the

System.out and System.err streams. With no convenient way to

redirect these to the user, they will end up in the MySQL server log

files. This is almost certainly not the ideal place for them, especially

since the MySQL log file conventionally follows a specific format

for its diagnostic messages. A future enhancement could disable

these streams in the most harmless way possible, or might redirect

them to a special Java log file.

2.2.3 Data Type Translation

At the moment when a Java routine is called, the parameters must

be translated from their MySQL data type to the equivalent Java

data type. For stored functions, the same holds for the return value

at the time the Java method completes. Only data type mappings

which can map to and from Java primitive types will be consid-

ered in scope for this project, with the exception of mappings to

and from java.lang.String and mappings to and from one-

dimensional arrays of char and byte. Mappings to and from any

other Java reference type are not in scope. This is an issue of time,

not feasibility, so the design of the parameter translation should

be easily extensible to accomodate future mappings to and from

more complex MySQL types which call for a Java reference type

to properly represent them. Since no straightforward mapping ex-

ists for result sets, there will not be any way in this version of the

system for a Java routine to return a result set. Adding parameter

support for result sets and cursors would be another interesting area

Charset Description Default collation

big5 Big5 Traditional Chinese big5 chinese ci

dec8 DEC West European dec8 swedish ci

cp850 DOS West European cp850 general ci

hp8 HP West European hp8 english ci

koi8r KOI8-R Relcom Russian koi8r general ci

latin1 cp1252 West European latin1 swedish ci

latin2 ISO 8859-2 Central European latin2 general ci

swe7 7bit Swedish swe7 swedish ci

ascii US ASCII ascii general ci

ujis EUC-JP Japanese ujis japanese ci

sjis Shift-JIS Japanese sjis japanese ci

hebrew ISO 8859-8 Hebrew hebrew general ci

tis620 TIS620 Thai tis620 thai ci

euckr EUC-KR Korean euckr korean ci

koi8u KOI8-U Ukrainian koi8u general ci

gb2312 GB2312 Simplified Chinese gb2312 chinese ci

greek ISO 8859-7 Greek greek general ci

cp1250 Windows Central European cp1250 general ci

gbk GBK Simplified Chinese gbk chinese ci

latin5 ISO 8859-9 Turkish latin5 turkish ci

armscii8 ARMSCII-8 Armenian armscii8 general ci

utf8 UTF-8 Unicode utf8 general ci

ucs2 UCS-2 Unicode ucs2 general ci

cp866 DOS Russian cp866 general ci

keybcs2 DOS Kamenicky Czech-Slovak keybcs2 general ci

macce Mac Central European macce general ci

macroman Mac West European macroman general ci

cp852 DOS Central European cp852 general ci

latin7 ISO 8859-13 Baltic latin7 general ci

cp1251 Windows Cyrillic cp1251 general ci

cp1256 Windows Arabic cp1256 general ci

cp1257 Windows Baltic cp1257 general ci

binary Binary pseudo charset binary

geostd8 GEOSTD8 Georgian geostd8 general ci

cp932 SJIS for Windows Japanese cp932 japanese ci

eucjpms UJIS for Windows Japanese eucjpms japanese ci

Table 3. Supported Character Sets

for future development.

With respect to java.lang.String parameters and char[]

parameters, some consideration needs to be given to the character

set encodings that can be used in MySQL and in the Java runtime.

Table 3 lists the character set encodings supported in MySQL 5.1

(see [11] for details). The two-byte UCS2 Unicode character set

will be used as the common encoding to translate all other charac-

ter sets into before being passed into the Java runtime. This means

that any character not in the Unicode Basic Multilingual Plane can-

not be represented, although MySQL provides no support for such

characters at the moment anyway.

2.2.4 Other Server/Runtime Communication

The MySQL database server has an extensible exception handling

mechanism, which includes the DECLARE ... HANDLER stored

procedure instruction for exception catching. The Java language

includes a very powerful exception handling mechanism, although

the behavior of uncaught exceptions which propogate all the way

out of the entry method is necessarily defined by the runtime. In-

tegration of these two exception handling mechanisms will be in

scope, so uncaught Java exceptions should continue to propogate

outward from the Java routine as MySQL exceptions. Further, new

exceptions will be created for errors resulting from incorrect Java](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/1098c2f3-e28c-4b9d-a1b5-fc236967b210-160513172820/75/Graduate-Project-Summary-4-2048.jpg)

![routine definitions or errors in parameter translation.

The Java runtime makes calls into a database using the Java

Database Connectivity API (JDBC, the msot recent version of

which is defined in the Java community process specification JSR-

54). The JDBC API provides a fixed interface for all database ven-

dors, and it is up to each vendor to provide an implementation

of that interface (called a JDBC driver) for their product. These

drivers communicate with the database server by opening a TCP

connection to the server, providing login credentials, sending the

desired command, and receiving the appropriate result. For Java

code which is not running on the same machine as the MySQL

server, this is an effective communication mechanism. Java stored

procedures, however, will be executing not only on the same ma-

chine as the database server, but in the same process. It could po-

tentially be much faster for JDBC calls to make a direct call to

the appropriate function in the MySQL server, rather than send-

ing commands over TCP sockets that require authorization, state-

ment parsing, and result interpretation. Unfortunately, the JDBC

API is prohibitively large, so a general-purpose native driver is

out of scope. However, as a special exception, the custom class-

loader class edu.sacredheart.cs.myjvm.MyClassLoader (see

Section 3.2.3) does make direct calls to native MySQL functions

without routing anything over a TCP connection.

3. Design

The features scoped in Section 2 could be added to the MySQL

server in a number of ways, and the design of additions and modifi-

cations to the server could affect issues like the platform avaiability

of the server, the performance of the Java routines, and the memory

consumption of client threads.

The most pressing design issue is the choice of how to in-

voke the Java Virtual Machine and call class methods within it.

The available design choices differ primarily in how tightly inte-

grated the MySQL server and the JVM become. At one extreme,

the MySQL server could simply make a system() call or similar,

invoking the java binary executable and passing the class name,

path, and arguments as strings. At the other extreme, the source

code for the JVM could be included with that of the MySQL server,

and MySQL could make direct calls into the internal processing

logic of the JVM. Section 3.2 presents the major design decisions

made in this project, and Section 3.2.2 presents the design deci-

sions made specifically to enable the MySQL server to make calls

into the JVM.

Before presenting these design decisions, it will be useful to

summarize the current MySQL server design. The server is actually

quite complex, offering platform-independent support for features

like threads, transactions, locking, logging, and replication. A full

presentation of the server design is beyond the scope of this paper,

but a summary of the design elements which support the use of

stored routines will be presented in Section 3.1.

3.1 MySQL Design

The MySQL server is implemented as a fairly standard client-server

application. When the server is first started, it goes through an ini-

tialization procedure, setting up the structures and parameters that

it will need to properly serve requests (see [10] for a much more

complete description of the server initialization process and many

other details of the server implementation). After initialization, the

server begins listening for network connections (the default port

that it listens on is port 3306, although administrators can change

this). From this point on, the main server thread does very little

other than listen for incoming connections and spawn new threads

:Client :Server :ClientThread :Parser :ParseTree

t

request()

create(thd)

handle one connection(thd)

do command(thd)

dispatch command(thd,packet)

mysql parse(thd,command)

create()

return()

mysql execute command(thd)

Figure 1. MySQL New Thread Prolog

to handle them.

Once a client is authenticated and a thread has been created

for it, the typical flow of events proceeds as in Figure 1. Af-

ter the client makes a request, the server creates a new thread to

handle the request. The thread begins execution by calling the

handle one connection server function. This calls the do command

server function, which calls the dispatch command server func-

tion, which invokes the parser via the mysql parse function. The

parser then parses the input, creating a parse tree class with objects

and structures representing the client request. The parser then calls

the execute server function, after which processing will differ ac-

cording to the type of command which the client requested.

This thread initialization prolog demonstrates a few features of

the design of the server. Firstly, note that the server is not sub-

divided into loosely coupled subsystems or classes. Most of the

core server features are implemented as globally accessible func-

tions. Features added to the server more recently, however, are

more likely to be encapsulated in classes. Secondly, this prolog in-

troduces a few of the elements which will be most important in the

design of Java routines.

After the server creates a new thread in Figure 1, most of the

remaining function calls pass a variable named thd. This variable

is a MySQL thread descriptor, and it is passed as the first argu-

ment to almost every function in the core server library. The thread

descriptor contains basically all data structures that are relevant to

a specific client request. This includes the objects which actually

represent the operating system thread, but also much more, such as

the parse tree, flags and states, references to the protocol handlers

and the table handlers, object caches, and status variables.

One element of the thread initialization prolog which is a sepa-

rate module is the parser. MySQL uses the GNU Bison parser gen-

erator to create a parser for the language understood by MySQL](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/1098c2f3-e28c-4b9d-a1b5-fc236967b210-160513172820/75/Graduate-Project-Summary-5-2048.jpg)

![runtime are already functional systems separately, this amounts

to saying that the most crucial element of their integration is the

boundary between the two systems.

The primary vehicle for that integration will be the Java Native

Interface (JNI). Section 3.2.1 discusses the JNI in general, and

Section 3.2.2 discusses the design of a subsystem which manages

the JVM linkage using JNI. Section 3.2.3 discusses the choice of

where and how to store compiled Java code so that the database

can find and execute it at runtime, and Sections 3.2.4 and 3.2.5

discuss changes to the objects introduced in Section 3.1.1 to add

Java routine functionality.

3.2.1 The Java Native Interface

The Java Native Interface is an API which provides a powerful bi-

directional communication channel between native code and code

running within the Java Virtual Machine. The JNI can be an ideal

framework with which to integrate C or C++ applications with Java

applications. A brief introduction to the JNI will be presented here,

but the interested reader can find much more detail in [8].

Since the Java Virtual Machine is not a specific software pack-

age, but rather a standard which many vendors have provided im-

plementations for, the features exposed through the JNI treat the

internal structure of the JVM as a black box. This is accomplished

through the use of the JNI environment pointer, defined in the

header file jni.h as type JNIEnv *. The environment pointer pro-

vides an interface through which requests for services can be made

from the JVM without revealing the internal structure of the virtual

machine.

The JNI basically allows running Java methods to call C or C++

(“native”) functions, and it allows running C or C++ code to call

methods of Java classes. Calls from Java to native code are facili-

tated by the native keyword in Java, which informs the compiler

that the definition of a method will be provided by a C or C++ func-

tion from a library which will be linked at runtime. The appropriate

function to call is determined either by following specific naming

conventions and exporting the function from a shared library, or

by explicitly registering the appropriate native function with the

JVM at runtime. Making calls from native code to Java methods

is achived through the JNI invocation interface. The invocation in-

terface allows native code to create an instance of the JVM, then

create class instances within the created JVM and call methods on

those classes.

Since the JVM is multithreaded, the JNI provides a mechanism

for native code to interact with the JVM in a multithreaded way. A

request can be made to attach the current native thread to the JVM,

which creates a new instance of java.lang.Thread to represent

the native thread in the JVM and provides an environment pointer

to the native thread through which it can request JVM services.

Since the Java language allows method overloading, it is neces-

sary to identify methods with both their name and their signature.

The signature of a method is formatted using the internal signa-

ture format defined in the JVM specification (see [9]). In this for-

mat, primitive types are represented with a single character, and

reference types have a form similar to Ljava/lang/String; in

which the type name begins with L and ends with ; and consists

of the fully-qualified name in between, with packages separated

by slashes. Arrays of any type are represented by prepending a

number of [ characters equal to the depth of the array to the type

name, so that a three-dimensional array of strings would be iden-

tified as [[[Ljava/lang/String;. This type format is important

1 #include ”jni.h”

2

3 class MyJVM {

4 // Using latest version of JNI, version 1.4

5 static const jint vm version = JNI VERSION 1 4;

6 // Singleton instance of this class

7 static class MyJVM ∗myjvm;

8 // The pointer to the JNI jvm descriptor

9 JavaVM ∗jvm;

10 // Environment descriptor for main thread

11 JNIEnv ∗env;

12 public:

13 static MyJVM ∗getMyJVM();

14 int startMyJVM();

15 int restartMyJVM();

16 int shutdownMyJVM();

17 ˜MyJVM();

18 JNIEnv ∗attachThread();

19 int detachThread();

20 static const unsigned char sigmap[NUM STATES] [

NUM CHARS];

21 static const unsigned char chmap[NUM ASCII CHARS];

22 private:

23 MyJVM();

24 };

Listing 3. The MyJVM Class

to understand when working with the JVM, as many calls need to

specify either a variable type or a method signature in this way.

3.2.2 Linking to the Java Virtual Machine

Linking to the JVM will be acomplished by the class MyJVM, pre-

sented in Listing 3. The class will encapsulate all of the JNI-related

processing that needs to be done to create and attach to the virtual

machine, so that other parts of the server do not have to make JNI

calls or even include JNI headers.

The MyJVM class is implemented as a singleton. During the

server intialization process described in Section3.1, the getMyJVM()

function will be called for the first time, which will in turn call the

private constructor to create the static instance myjvm. Subsequent

calls to the getMyJVM() function by native client threads will re-

turn this static instance. This design guarantees that there will never

be more than one JVM defined in a single database instance. Native

client threads can also call the attachThread() function to attach

the current native thread to this JVM.

The arrays sigmap and chmap implement the finite state ma-

chine in Figure 2 which parses the language of method signatures

mentioned in Section 3.2.1. They are defined at the JVM level in

part because the internal method signature format is defined by

the JVM and in part because this ensures that the arrays will not

be defined more than once in the application. In Figure 2, transi-

tions labelled with α represent the character set [a-zA-Z0-9$ ]

(which are defined in [9] to be legal to use as part of a Java class

name), and the transitions labelled β represent the character class

[ZBCSIJFD] (the JNI single character representations of the Java

primitive types).

3.2.3 Locating Java Class Files

After linking to the JVM, the next most pressing decision to make

is where and how to store the Java code. The simplest solution

would be to store the Java classes on the file system of the same](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/1098c2f3-e28c-4b9d-a1b5-fc236967b210-160513172820/75/Graduate-Project-Summary-7-2048.jpg)

![0 1

2

3 4 5

6 7

8

9 10 11

12

13

(

β

[

β

[

L

L

α

α

/

α

;

)

V

β

[

L

β

[

L α

α ;

/

α

Figure 2. Method Signature Parser

physical or virtual machine that the database instance is running

on. This is, in fact, the solution which the ISO specifications [2, 5]

assume systems will use. There are a number of potential problems

with this solution, however. The most pressing concern is that this

solution requires that all developers who will be allowed to write

Java routines be given access to the file system that the database

resides on. The database is a very sensitive resource, and access

to the file system of a server is a very powerful privilege to grant

on such a sensitive resource. Further, this increases the surface

area which must be reliably secured. Security concerns aside, stor-

ing Java code locally also makes administration more difficult, as

database administrators would then have to work partly with the

file system and partly with the database to properly manage privi-

leges and resolve issues.

Given these drawbacks, this project will not assume that Java

code is stored in individual class files on the database server.

Rather, the Java code will be stored in a table in the mysql schema.

Of course, this means that ultimately the Java code is stored on the

file system used by the database, but this code will be stored in files

which are already secured and managed by the database itself, and

administrative tasks related to this code can be carried out using

only the features of the database. Table 5 describes the jclass

table which Java code will be stored in.

The biggest drawback to storing java code in the database itself

is that the runtime environment will not know how to find it. Java

code is located by the runtime with the use of Classloaders, and the

default Classloader searches the file system directories specified by

a classpath variable to find class bytecode representations when

resolving new class references. However, for flexibility, custom

Classloaders can be created which locate Java bytecode by other

means, and in fact these Classloaders can be arranged hierarchi-

cally such that a Classloader delegates the task of locating a class

first to its parent, and then employs its own techniques if the parent

Classloader is unable to find the requested class (see [7] for a more

thorough treatment of the subject).

To locate the Java class files stored in the jproc table, the cus-

tom Classloader MyClassLoader (see Listing 4) will be added to

the Classloader chain of the first class defined as part of executing

a Java routine. For performance reasons, the work of actually re-

trieving the class definition from the database is done by the native

method findClass0, which makes a direct call into the MySQL

Field Type Description

class name varchar(200) The fully-qualified name

of the class

package name varchar(100) The package which the

class resides in

internal name varchar(200) The fully qualified name

of the class, in JVM inter-

nal format

library name char(50) The name of the JAR

archive which this class

was loaded from

short name varchar(100) The unqualified name of

the class

major version tinyint(3) The major class version

number

minor version tinyint(3) The minor class version

number

platform version enum(...) The java platform version

which this class was com-

piled under

is interface enum(...) Indicates whether or not

this class is an interface

modifiers set(...) Indicates what modifiers

were listed for this class

size int(10) The size of the bytecode

for this class, in bytes

created timestamp The date this class was

loaded into the database

bytecode longblob The binary definition of

this class

Table 5. The mysql.jclass Table

1 package edu.sacredheart.cs.myjvm.launcher;

2

3 public final class MyClassLoader extends ClassLoader {

4 @Override

5 protected Class<?> findClass(String name) throws

ClassNotFoundException { ... };

6 private native byte[] findClass0(String className);

7 }

Listing 4. The MyClassLoader Class

table handler for the jclass table and retrieves the bytecode. A

similar set of native calls for more general features such as exe-

cuting queries, opening and iterating over cursors, and managing

transaction could be the basis for a fully native JDBC Driver.

In addition to locating class files, the decision to store Java

code in the database also raises the question of how to catalog

methods and resources. As for methods, to simplify the design,

only static class methods will be permissible as Java routines. Any

attempt to allow instance methods to be used as Java routines

would necessarily imply that the database has to have a means of

creating class instances. Further, restricting routines defintions to

statically defined methods imposes no loss of generality, since a

static wrapper method could be written to perform any instantiation

which the database itself could be expected to perform. To keep

a catalog of which methods are available in which classes, the

tool which loads classes into the mysql.jclass table should also

populate the mysql.jmethod table described in Table 6. This table

tracks which static methods are available in which classes, and

provides method level details for summary and analysis.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/1098c2f3-e28c-4b9d-a1b5-fc236967b210-160513172820/75/Graduate-Project-Summary-8-2048.jpg)

![Field Type Description

signature varchar(1000) The fully-qualified class

name and parameter list

for the method

class name varchar(200) The fully-qualified class

name for the method

method name varchar(100) The name of the method

method descriptor varchar(500) The JNI method descrip-

tor for the method

num args int(11) The number of parame-

ters the method accepts

has return enum(...) Indicates whether or not

this method has a return

value

return type varchar(100) If the method has a return

value, this is the fully-

qualified type which is re-

turned

modifiers set(...) The list of modifiers

which the method was

defined with

throws exceptions enum(...) Indicates whether or not

this method throws any

checked exceptions

exceptions varchar(300) A list of the exceptions

thrown by this method, if

any

Table 6. The mysql.jmethod Table

Field Type Description

resource name varchar(200) The file name (minus the

path)

file name varchar(300) The file name, with the

patch included

package name varchar(100) The name of the java

pacakge which this re-

source is contained in

library name char(50) The name of the JAR file

which this resource was

loaded from

size int(10) unsigned The size of this resource,

in bytes

contents longblob The resource, represented

in raw binary form

Table 7. The mysql.jresource Table

It is also necessary to track class resources in the database.

Resources are file system objects which would be stored with the

Java class file definitions and accessible at runtime. Frequently,

this includes objects like property configuration files, XML-based

configuration files, or documents like XSD Schemas. As with

class files, resource files will be stored in the database, in the

mysql.jresource table defined in Table 7.

3.2.4 Creating Java Stored Routines

A primary goal of this project is that calling Java routines should

be as similar as possible to calling native routines. From a design

perspective, that means that the classes and tables presented in Sec-

tion 3.1.1 should also be used to represent Java routines. Making all

changes internally within the functions which are already defined

in these classes will ensure that calling and executing Java routines

1 CREATE DEFINER = ’root’@’localhost’ PROCEDURE ‘hello‘(

2 IN str VARCHAR(100)

3 )

4 LANGUAGE JAVA PARAMETER STYLE JAVA

5 EXTERNAL NAME ’edu.sacredheart.cs.myjvm.hello.Hello(

java.lang.String)’;

6 DETERMINISTIC

7 CONTAINS SQL

8 SQL SECURITY DEFINER

9 COMMENT ’Outputs a greeting.’;

Listing 5. A Basic Java Stored Routine

Column Data Type Change

external name varchar(1000) Column added

language enum(’SQL’,’JAVA’) Column can now store ei-

ther SQL or JAVA

is external enum(’YES’,’NO’) Column added

body longblob Can now be null, since

the ‘body’ of external

routines is stored else-

where

body utf8 longblob Can now be null, since

the ‘body’ of external

routines is stored else-

where

Table 8. Changes to the mysql.proc table

is as seamless as possible.

Changes will obviously have to be made to the grammar itself,

to accomodate the slightly different syntax required for defining

Java routines. Note that there are directives in Listing 1 between

the end of the parameter list and the beginning of the body of

the routine. These directives are referred to as the characteristics

of the routine. The ISO standard [5] distinguishes Java routines

from native ones using a new set of options for these character-

istics, as in Listing 5. Specifically, the LANGUAGE characteristic

may now specify JAVA, and an optional PARAMETER STYLE JAVA

characteristic may now appear. Routines defined in languages other

than the database native language are referred to as external lan-

guages in the specifications, so the characteristic EXTERNAL NAME

is followed by a string which tells the database where to find the

code for the routine. For example, in Listing 5, the bytecode for

the class edu.sacredheart.cs.myjvm.hello should be in the

mysql.jclass table, and this class should have a static method

named Hello described in the mysql.jmethod table which takes

a single String argument.

As mentioned in Section 3.1.1, the most important data struc-

tures in the creation of a stored procedure are the table mysql.proc

and the class sp head. The mysql.proc table will be modified

as summarized in Table 8. The design of the sp head class will

not change very much (of course the implementation of some of

the functions in it will need modification), but a single new pri-

vate class variable of type MyJThread will be added. See Listing 7

in Section 3.2.5 for a description of the MyJThreadClass class.

Note that the sp head class in Listing 2 has a member variable of

pointer type st sp chistics. This structure defines the charac-

teristics of the routine, and the definition of this structure with the

needed changes for Java routines is presented in Listing 6.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/1098c2f3-e28c-4b9d-a1b5-fc236967b210-160513172820/75/Graduate-Project-Summary-9-2048.jpg)

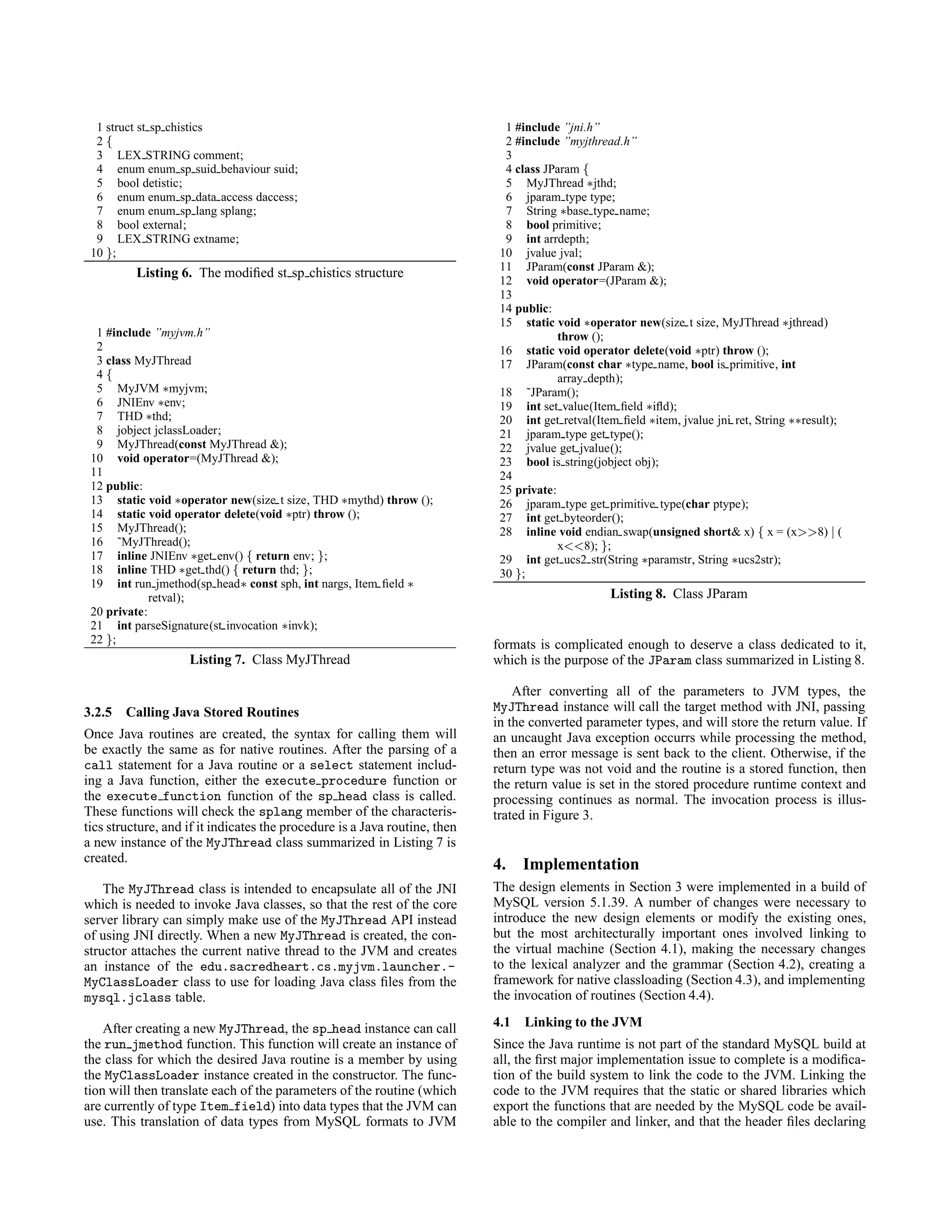

![:Server :Parser :SpHead :MyJThread :Loader :JParam :JVM

t

parse()

create()

call()

create()

attach()

create()

run jmethod(sp head *sph, Item field *params)

loadClass()

jparams = create(params)

invoke(jparams)

return()

return()

return()

Figure 3. Java Routine Invocation

any needed prototypes are available to the compiler. To meet these

requirements, the shared library jvm.dll and the import library

jvm.lib (for Windows platforms) were copied to the sql/lib

source code directory, and the header file jni.h was copied to the

sql/include source code directory. These files are available from

any standard Java Development Kit.

MySQL uses a cross-platform build system named CMake1

to manage the build process. CMake allows the developer to de-

fine abstract libraries, which be sets of code files from the current

project, code files from other project, or shared native libraries.

The CMake buils system is rather interesting in that it does not ac-

tually build the project. Rather, it generates a configuration file for

the development file or build system of your choice. For instance,

on Windows platforms, CMake can generate Visual Studio solution

files, and on Linux platforms it can generate makefiles. The CMake

system maintains a set of properties for each library that the user

defines, and allows these libraries to be linked, and when it is run

the appropriate commands or syntax will be generated in the target

build system to effectively carry out the declared directive. The

major changes made to the CMake configuration file are presented

in Listing 9.

Although making the shared JVM library, the imported JVM

library (on Windows), and the jni.h header file available to the

build system is enough to compile and link the application, the full

Java Runtime Environment is required when executing the applica-

tion in order for the application to operate successfully. Further, the

JRE must be compatible with the shared JVM library linked by the

build system. Compiling the application under a Java 6 JVM and

then running the application under a Java 5 JRE will likely lead to

crashes.

1 http://www.cmake.org

1 SET (JVM HOME ${PROJECT SOURCE DIR}/sql/lib )

2 SET (JNI HOME ${PROJECT SOURCE DIR}/sql/include )

3

4 INCLUDE DIRECTORIES( ${JNI HOME}/include )

5

6 ADD LIBRARY(jvm SHARED IMPORTED)

7

8 SET TARGET PROPERTIES(jvm PROPERTIES

9 IMPORTED IMPLIB ${JVM HOME}/lib/jvm.lib

10 IMPORTED LOCATION ${JVM HOME}/lib/jvm.dll

11 IMPORT PREFIX ””

12 IMPORT SUFFIX .dll

13 )

14

15 SET (MYSQLD CORE LIBS mysys zlib dbug strings yassl

taocrypt vio regex sql jvm)

16 TARGET LINK LIBRARIES(mysqld ${

MYSQLD CORE LIBS} ${

MYSQLD STATIC ENGINE LIBS})

Listing 9. CMakeList.txt

4.2 Modifying the Grammar

Fortunately, since the MySQL language for routines is already

strongly compliant with the ISO standard [1], only a fairly small

set of changes had to be made to the language processing subsys-

tem. Since new keywords need to be added to the grammar, the

first changes to make are in the lexical analyzer. MySQL uses a

custom lexical analyzer which relies on constructing a perfect hash

of symbols at compile time. The symbols are defined in lex.h,

and the keywords JAVA, PARAMETER, STYLE, EXTERNAL, and NAME

were added to the definition of syntactic symbols.

For parsing, MySQL uses the GNU Bison parser generator.

Bison creates the parser from a language specification grammar,

which for MySQL is defined in the file sql yacc.yy. For each

symbol added to lex.h, a corresponding %token was added to

the header of the grammar. The production rule for stored routine

characteristics (See Section 3.1.1 for a discussion and examples of

routine characteristics) was then modified as in Listing 10. Note

the presence of the LANGUAGE SYM JAVA SYM rule, which allows

a routine to be declared as a Java routine, and the EXTERNAL SYM

NAME SYM TEXT STRING sys rule which sets the external prop-

erty of the sp chistics object in the parse tree and stores the fully

qualified name of the Java method in the extname field.

Beyond this, only two other changes to the grammar are nec-

essary. A stored routine is normally ended with an sp proc stmt

production rule, which can be a single statment or a BEGIN...END

block. External routines will not have such a statement, however,

as the “body” of external routines is defined in a separate code file.

Listing 11 relaxes the condition that a stored procedure statement

cannot be empty for external routines. Additionally, stored func-

tions must include a RETURN statement as one of the statements in

the sp proc stmt body. However, external functions will not have

such a RETURN statement, as the return value will be managed sep-

arately by the language runtime. Listing 12 shows modifications to

the sf tail production rule which relax this constraint for exter-

nal functions.

4.3 Classloading

Implementing native classloading was one of the most interesting

challenges of this project. The design ideas were discussed in Sec-

tion 3.2.3, but a number of choices remain for implementation.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/1098c2f3-e28c-4b9d-a1b5-fc236967b210-160513172820/75/Graduate-Project-Summary-11-2048.jpg)

![1 static int

2 db find jclass(THD ∗thd, const char ∗name, st bytecode ∗∗clazz

)

3 {

4 TABLE ∗table;

5 int ret;

6 char ∗ptr;

7

8 ∗clazz= 0; // In case of errors

9 if (!(table= open jclass table for read(thd, &

open tables state backup)))

10 DBUG RETURN(SP OPEN TABLE FAILED);

11

12 st bytecode ∗tmp= (st bytecode ∗) alloc root( thd−>mem root

, sizeof(st bytecode) );

13 if ((ptr= get field(thd−>mem root,

14 table−>field[

15 MYSQL JCLASS FIELD INTERNAL NAME

16 ])) == NULL)

17 {

18 ret= SP GET FIELD FAILED;

19 goto done;

20 }

21 tmp−>name= ptr;

22 tmp−>len= table−>field[MYSQL JCLASS FIELD SIZE

]−>val int();

23

24 if ((ptr= get field(thd−>mem root,

25 table−>field[

26 MYSQL JCLASS FIELD BYTECODE

27 ])) == NULL)

28 {

29 ret= SP GET FIELD FAILED;

30 goto done;

31 }

32

33 tmp−>data= ptr;

34 (∗clazz)= tmp;

35

36 close system tables(thd, &open tables state backup);

37 table= 0;

38

39 ret= SP OK;

40 ...

41 DBUG RETURN(ret);

42 }

Listing 14. The db find jclass Function

named RegisterNatives. The MyJThread constructor will reg-

ister the findClass0 method of the MyClassLoader class to a

function named get jclass bytes, which is presented in List-

ing 16. The MyJThread constructor then creates an instance of the

MyClassLoader class, which will be used as the defining class-

loader for the class which is called when the MyJThread object is

executed. See Listing 15 for the full MyJThread constructor (with

some exception handling elided).

At this point, native classloading is now setup. If the Java class

invoked when the MyJThread instance runs encounters a class def-

inition which is not yet defined in the runtime, the defining class-

loader for that class (namely, the MyClassLoader instance which

was created in the MyJThread constructor) will first delegate to

its parent classloader (which would be the bootstrap classloader,

in this instance). The bootstrap classloader will be unable to find

the class definitions, since they exist in database tables and not

on the file system, so it will indicate failure. The MyClassLoader

instance will then call the native method defineClass0, which

1 MyJThread::MyJThread() {

2 myjvm= MyJVM::getMyJVM();

3 env= myjvm−>attachThread();

4 ...

5 // Thread Bootstrapping: Natively define the

MyClassLoader loader

6 st bytecode ∗my cls loader cd= sp find jclass(thd, ”edu

.sacredheart.cs.myjvm.launcher.MyClassLoader”)

;

7

8 jclass myClassLoaderClass= env−>DefineClass(

my cls loader cd−>name, NULL, (jbyte ∗)

my cls loader cd−>data, my cls loader cd−>

len);

9 ...

10 jclass launchClassLoader = env−>FindClass(

MY JAVA ENTRY CLASSLOADER);

11 // Linkage: Native method registration

12 JNINativeMethod nm;

13 nm.name= ”findClass0”;

14 nm.signature= ”(Ljava/lang/String;)[B”;

15 nm.fnPtr= &get jclass bytes;

16 env−>RegisterNatives(launchClassLoader, &nm, 1);

17 ...

18 // Create classloader instance

19 jmethodID myClassLoaderCtor= env−>GetMethodID(

myClassLoaderClass, ”<init>”, ”()V”);

20 ...

21 jclassLoader= env−>NewObject(myClassLoaderClass,

myClassLoaderCtor);

22 ...

23 }

Listing 15. MyJThread Constructor

1 #include ”myjthread.h”

2

3 jbyteArray JNICALL get jclass bytes(JNIEnv ∗env, jobject obj,

jstring lkp class nm)

4 {

5 // Get the THD∗ for this pthread

6 THD ∗thd= my pthread getspecific ptr(THD∗, THR THD);

7 const char ∗class name = env−>GetStringUTFChars(

lkp class nm, false);

8 st bytecode ∗clazz= sp find jclass(thd, class name);

9 env−>ReleaseStringUTFChars(lkp class nm, class name);

10 jbyteArray data= env−>NewByteArray(clazz−>len);

11 env−>SetByteArrayRegion(data, 0, clazz−>len, (jbyte ∗)

clazz−>data );

12 return data;

13 }

Listing 16. MyClassLoader Callback

has been linked to the function get jclass bytes. Note that

code running inside the JVM is making a direct call to the

get jclass bytes function, which is running in the same process

space, rather than opening a new Socket and making a database re-

quest over JDBC. This is a strong advantage to the tight coupling

that JNI provides for an integration project like this, and it is easy

to see how a similar set of linked functions could be created to

construct a fully native JDBC driver.

4.4 Invocation

With classloading setup and working, all that remains is to create

the functions which invoke the target methods of Java routines.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/1098c2f3-e28c-4b9d-a1b5-fc236967b210-160513172820/75/Graduate-Project-Summary-13-2048.jpg)

![This responsibility belongs to the run jmethod function, which

is presented in Listings 17 and 18. The first half of the function

deals with finding and loading the correct Java class file, finding

the method details from the mysql.jmethod table, parsing the

method signature, and using the JParam class to translate the rou-

tine parameters from MySQL data types to Java data types. The

second half of the function makes JNI calls to execute the method,

passing in the correctly translated parameters, and saves the return

value (if the return type is not void), which is then set as the return

value of the routine.

The run jmethod function starts by calling the sp find jmethod

function. This function similar to the sp find jclass function

in that it accesses the mysql.jmethod table with native table

handlers and stores the information for the desired method in a

structure in memory. The parser in Figure 2 is then called on this

structure, and it will parse the method signature and create an ar-

ray of parameter and return types appropriate for this method. The

sp find jclass method is then called to get the bytecode for

the class which defines the target method. This class is then de-

fined using a JNI DefineClass call. Note that the instance of the

MyClassLoader class created in the constructor is passed in this

call to DefineClass. This makes the jClassLoader instance of

the MyClassLoader class the defining classloader for this class,

which means that the jClassLoader instance will be called upon

when any other unknown class is encountered in this method call

(as described in Section 4.3). The JNI ID of the target method is

then retrieved with a JNI call to GetStaticMethodID. The reason

for requiring methods which implement Java routines to be static

is evident here - if instance methods were allowed, what instance

would be used to get the JNI Method ID? No instance of the target

class is readily available, although the class itself is, which makes

retrieving static methods straightforward.

The final loop in Listing 17 translates the routine parameters

from their MySQL data type (an instance of the Item field class)

to their associated Java data type. This is done primarily with the

get jvalue function in the JParam class, which is dedicated

solely to translating data between MySQL types and Java types.

All MySQL integer types are allowed to translate to some Java nu-

meric type, and the MySQL float and double types will translate

as well. The exact precision numeric type cannot be translated to

any Java primitive, although in the future it could be translated to

a Java object type. It is worth noting that MySQL allows integer

data types to be either signed or unsigned, whereas Java allows

only signed types. This means that an incompatibility may arise

at runtime if the value passed in an unsigned mysql type is too

large to fit into the corresponding Java signed type. For example,

the TINYINT type in MySQL is a one-byte value, so its unsigned

variant can store numbers from 0 to 255. The Java byte primitive

is also a one-byte value, but it is always signed so it can only accept

values from −128 to 127. If an unsigned TINYINT with a value of

250 is passed to a method where a byte is accepted, an exception

will be raised and the caller will be notified.

Some special consideration is given to character types during

data type translation. The MySQL CHAR and VARCHAR data types

will map to the Java types byte[], char[], or java.lang.String.

The implementation of this mapping needs careful treatment, how-

ever, since MySQL and Java use different character set encodings

for strings. MySQL allows character data to be stored in many

encodings, as listed in Table 3. Java, on the other hand, stores all

string and character data internally using the UTF-16 encoding.

MySQL does not currently have support for UTF-16, although it

does support the older UCS2 encoding, and UTF-16 is backwards-

1 int MyJThread::run jmethod(sp head∗ const sph, int nargs,

Item field ∗retval)

2 {

3 st invocation ∗invk= sp find jmethod(thd, sph−>

m chistics−>extname.str);

4

5 int sig parse ret= this−>parseSignature(invk);

6 ...

7 st bytecode ∗target def= sp find jclass(thd, invk−>

className);

8 ...

9 jclass target class= env−>DefineClass(target def−>

name, jclassLoader, (jbyte ∗) target def−>data,

target def−>len);

10 ...

11 jmethodID target method= env−>GetStaticMethodID(

target class, invk−>methodName, invk−>

internalSignature);

12 ...

13 sp rcontext ∗rctx= thd−>spcont;

14 jvalue ∗target method params= (jvalue ∗) alloc root(thd−>

mem root, nargs ∗ sizeof(jvalue) );

15 if(nargs)

16 {

17 for(int k= 0; k < nargs; k++)

18 {

19 Item field ∗nxt arg= (Item field ∗) rctx−>get item(k);

20 int cast failed= invk−>jparams[k]−>set value(nxt arg);

21 if(cast failed)

22 {

23 my error(ER JPARAM CAST, MYF(0), k+1, invk−>

fullSignature);

24 return ER JPARAM CAST;

25 }

26 target method params[k]= invk−>jparams[k]−>

get jvalue();

27 }

28 }

Listing 17. Invoking Java Routines (Part 1)

compatible with UCS2. The general procedure, then, will be to

convert MySQL strings from whatever encoding they are currently

in to UCS2, and the create Java strings or characters using this UCS2

data. There is one more implementation issue here, though, and

that is the fact that UCS2 is a multi-byte data format (each character

is represented by two bytes). This means that big-endian and little-

endian systems may have different expectation as to the layout of

this data in memory. The JParam class therefore has functions to

detect the endian-ness of the platform and swap the bytes in each

UCS2 character if the translation is not in the correct endian mode

for the platform. The allowed data type translations are listed in

Table 9, in which square brackets indicate the MySQL type can

map to a one-dimensional array of the Java type, ‘Y’ indicates that

the two types can map, and ‘S’ indicates that the two types can map

but that unsigned values could potentially overflow.

The rest of the run jmethod function is presented in List-

ing 18. After translating the routine parameters to Java types, the

target method is invoked. If the return type is void, the function

returns, otherwise the return value is stored in the jni ret vari-

able. The JParam class is then used to translate this value back

into a MySQL type, which is stored in the return value field. At this

point the Java routine has been called successfully, and the MySQL

server completes via its usual path and returns results to the caller

over the network connection.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/1098c2f3-e28c-4b9d-a1b5-fc236967b210-160513172820/75/Graduate-Project-Summary-14-2048.jpg)

![1 jvalue jni ret;

2

3 switch(invk−>jreturn−>get type())

4 {

5 case JPARAM TYPE VOID :

6 env−>CallStaticVoidMethodA(target class, target method

, target method params);

7 ...

8 break;

9 case JPARAM TYPE BOOLEAN :

10 jni ret.z= env−>CallStaticBooleanMethodA(target class,

target method, target method params);

11 break;

12 case JPARAM TYPE BYTE :

13 jni ret.b= env−>CallStaticByteMethodA(target class,

target method, target method params);

14 break;

15 case JPARAM TYPE CHAR :

16 jni ret.c= env−>CallStaticCharMethodA(target class,

target method, target method params);

17 break;

18 case JPARAM TYPE SHORT :

19 jni ret.s= env−>CallStaticShortMethodA(target class,

target method, target method params);

20 break;

21 case JPARAM TYPE INT :

22 jni ret.i= env−>CallStaticIntMethodA(target class,

target method, target method params);

23 break;

24 case JPARAM TYPE LONG :

25 jni ret.j= env−>CallStaticLongMethodA(target class,

target method, target method params);

26 break;

27 case JPARAM TYPE FLOAT :

28 jni ret.f= env−>CallStaticFloatMethodA(target class,

target method, target method params);

29 break;

30 case JPARAM TYPE DOUBLE :

31 jni ret.d= env−>CallStaticDoubleMethodA(target class,

target method, target method params);

32 break;

33 case JPARAM TYPE OBJECT :

34 jni ret.l= env−>CallStaticObjectMethodA(target class,

target method, target method params);

35 break;

36 case JPARAM TYPE UNKNOWN :

37 // Fall−through

38 default :

39 return 1;

40 }

41 ...

42 String ∗ret bytes;

43 if(invk−>jreturn−>get retval(retval, jni ret, &ret bytes))

44 {

45 return 1;

46 }

47 retval−>save str value in field(retval−>field, ret bytes);

48 return 0;

49 }

Listing 18. Invoking Java Routines (Part 2)

Java Types

B S I J F D Z C Str

M CHAR [] [] Y

y BINARY []

S TEXT [] [] Y

Q BLOB

L ENUM

SET

T BIT S Y

y TINYINT S Y Y Y Y

p BOOLEAN S Y Y Y Y

e SMALLINT S Y Y

s MEDIUMINT S Y

INT S Y

BIGINT S

FLOAT Y

DOUBLE Y

DECIMAL

DATE

DATETIME

TIMESTAMP

TIME

YEAR S Y Y

Table 9. Allowed data type translations

5. Summary and Future Work

The design of the project’s major architectural elements leaves

room for the addition of several new features in the future. Several

optimization features could improve the performance or memory

profile of Java routines, and a number of additional features could

be added which would considerably extend the flexibility or usabil-

ity of Java routines in the server.

For performance optimization and administration purposes, it

would be interesting to create several new server variables related

to Java routines. MySQL server variables control many aspects of

the system, such as the size of certain object caches and memory

pools. Modifying these configuration variables is an important part

of performance optimization, and it could be important to manage

JVM variables in the same way. For instance, such variables could

control the amount of memory allocated to the JVM, or the size of

the stack allocated for each thread.

To further optimize performance, a caching structure could be

implemented for the Java bytecode lookups and the Java routine

definitions. MySQL makes use of caches for many other database

objects, including stored procedure definitions, statements, and

some result sets, all to good effect.

It would be interesting to integrate the Java Authentication and

Authorization Services into the system, so that user-based access

control could be seamlessly integrated. Such a security solution

would ideally also involve extending the set of available GRANT

and REVOKE targets, so that database administrators could manage

access to sensitive Java resources the same way they manage access

to sensitive database resources.

The most interesting additional feature that could be added to

this framework would be support for a fully native JDBC driver. A

native driver would give much better performance for JDBC calls

than routing requests and responses over TCP, even if the packets

are travelling over the loopback interface on the server. A native

JDBC driver would take full advantage of the fact that the JVM

and the database are running in the same process space, and the

native classloader described in Section 4.3 demonstrates that the](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/1098c2f3-e28c-4b9d-a1b5-fc236967b210-160513172820/75/Graduate-Project-Summary-15-2048.jpg)

![framework would support such a driver.

An even more ambitious goal would be to implement the

other half of the ISO specification and bring user defined types

to MySQL using the Java language. This would require a much

more extensive change to the grammar than that which was imple-

mented here, but the payoff could be worth the effort, as MySQL

does not support any form of user-defined types at the present time.

Finally, the data type translation layer could be extended. This

layer currently support translations for basic interger and floating

point types, as well as character and string types. Support could be

added for date and time types, exact numeric types, and even more

exotic types like ENUM, SET, or GEOMETRY types.

The primary goal of this project, however, which was to build a

robust and extensible framework for linking the MySQL database

server to the Java runtime environment, has been very successful.

The MySQL/JVM framework provides a fully functional environ-

ment for loading, creating, and calling Java routines; a manage-

able framework for storing and locating class files; and a well-

encapsulated API for invoking Java methods and translating data

types. Further optimizations could be applied, and more features