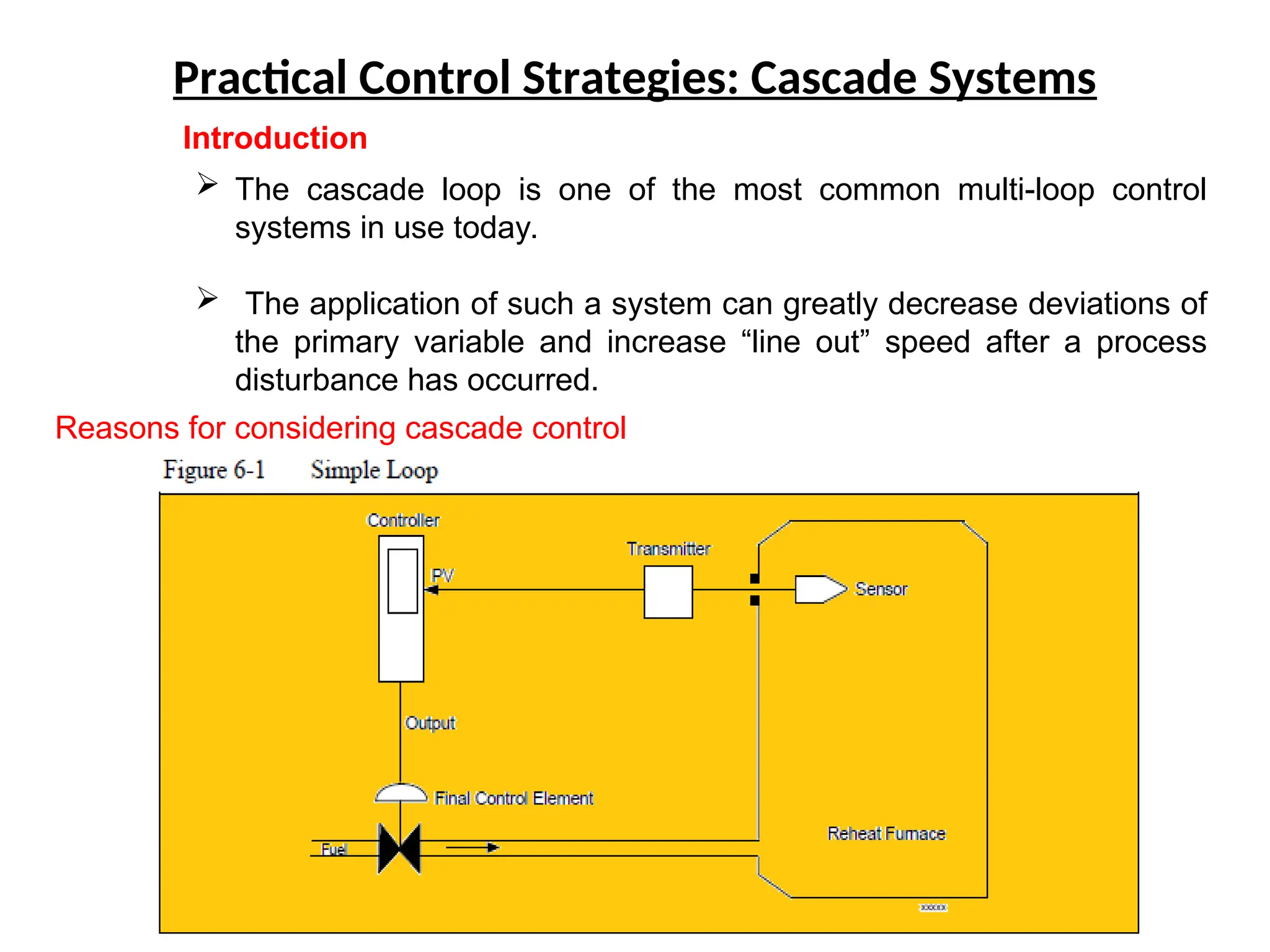

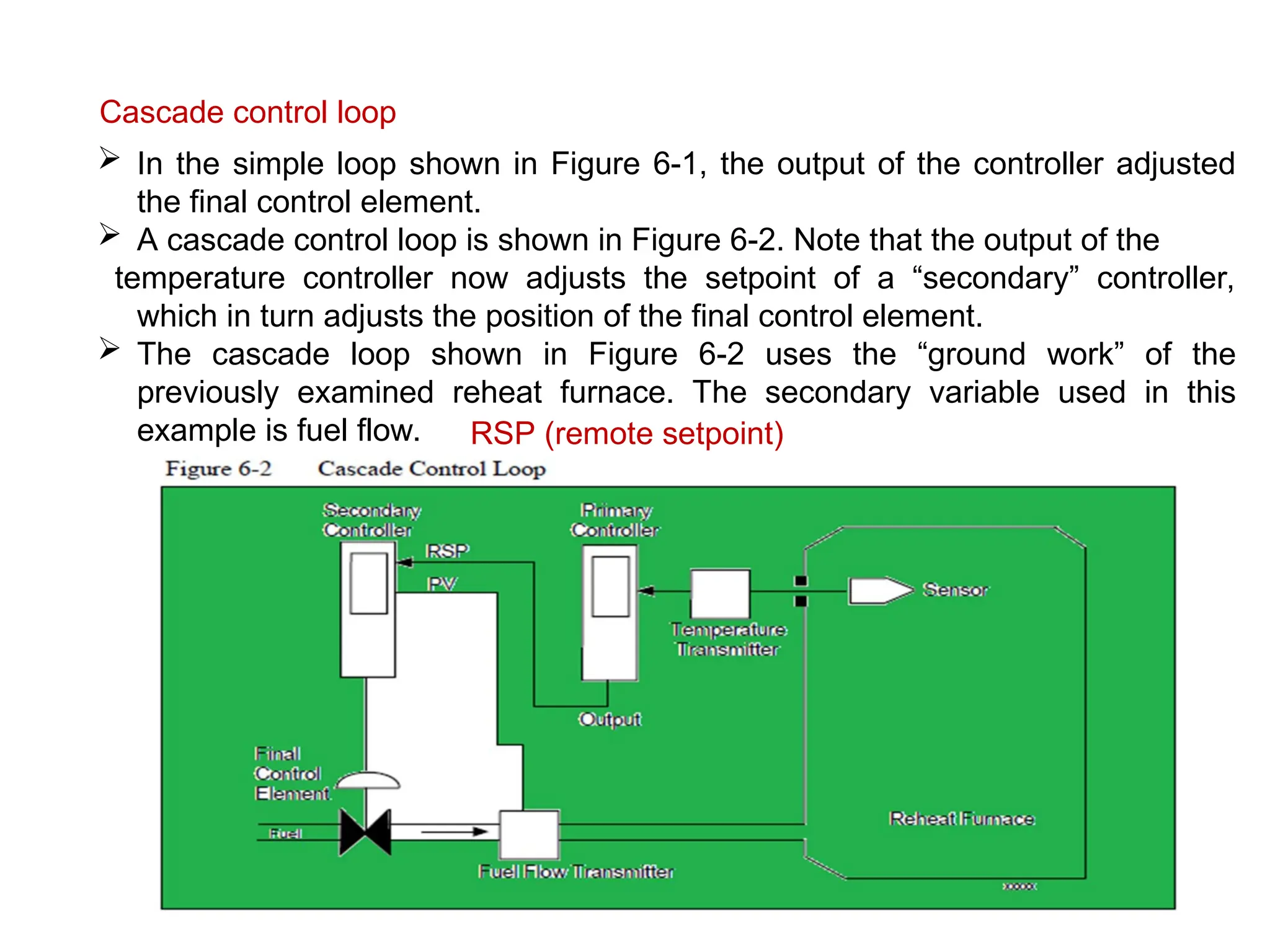

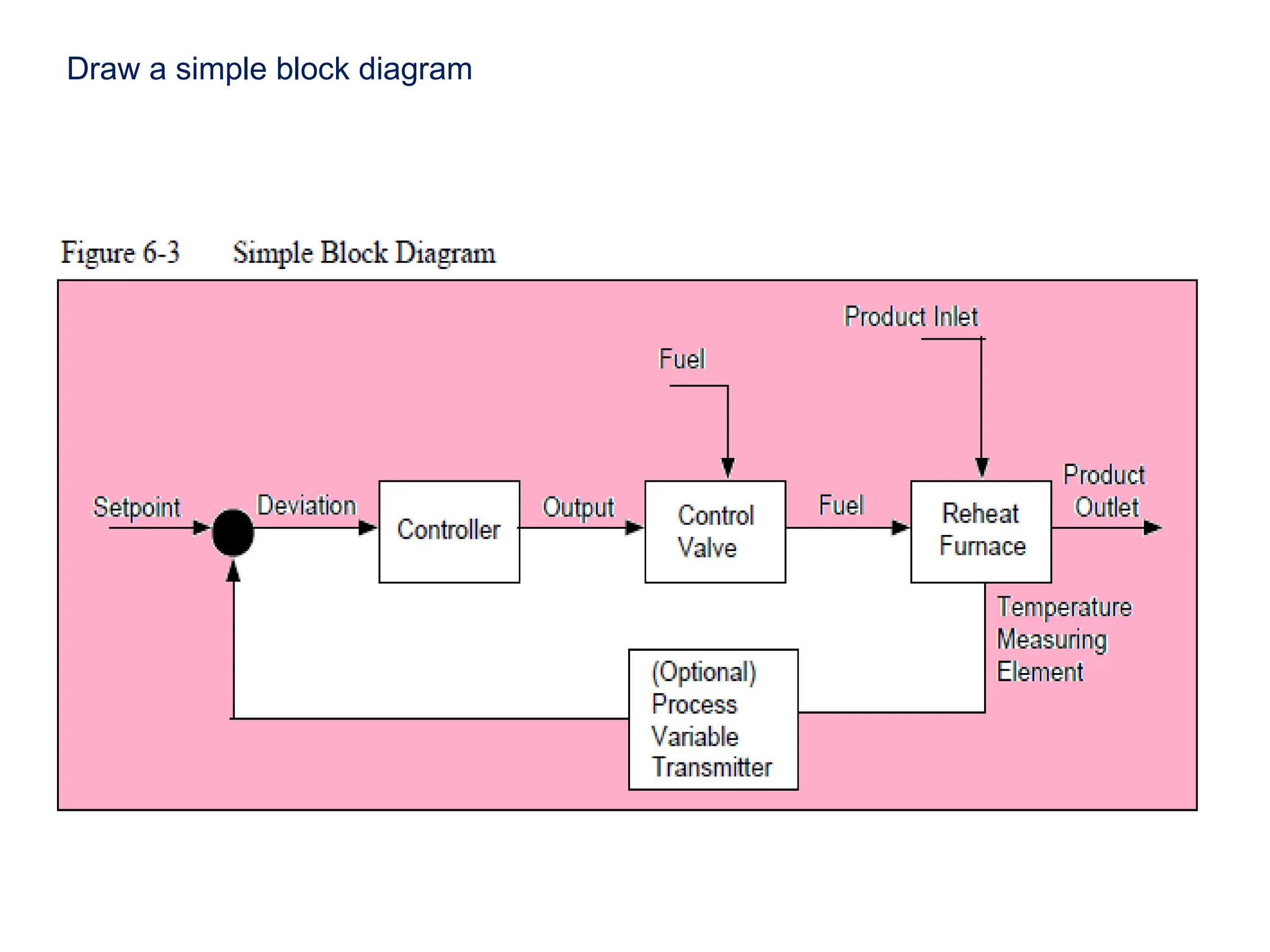

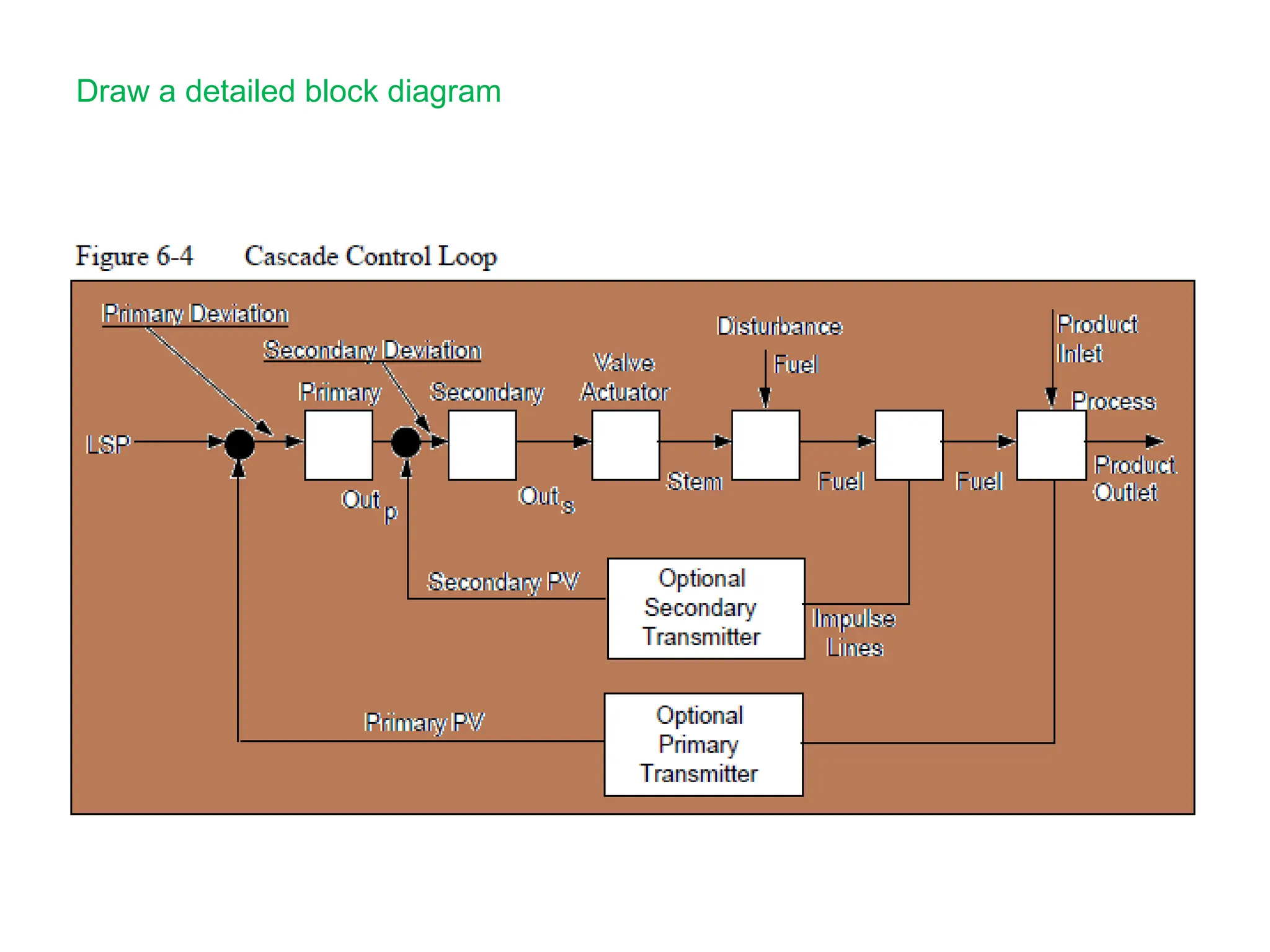

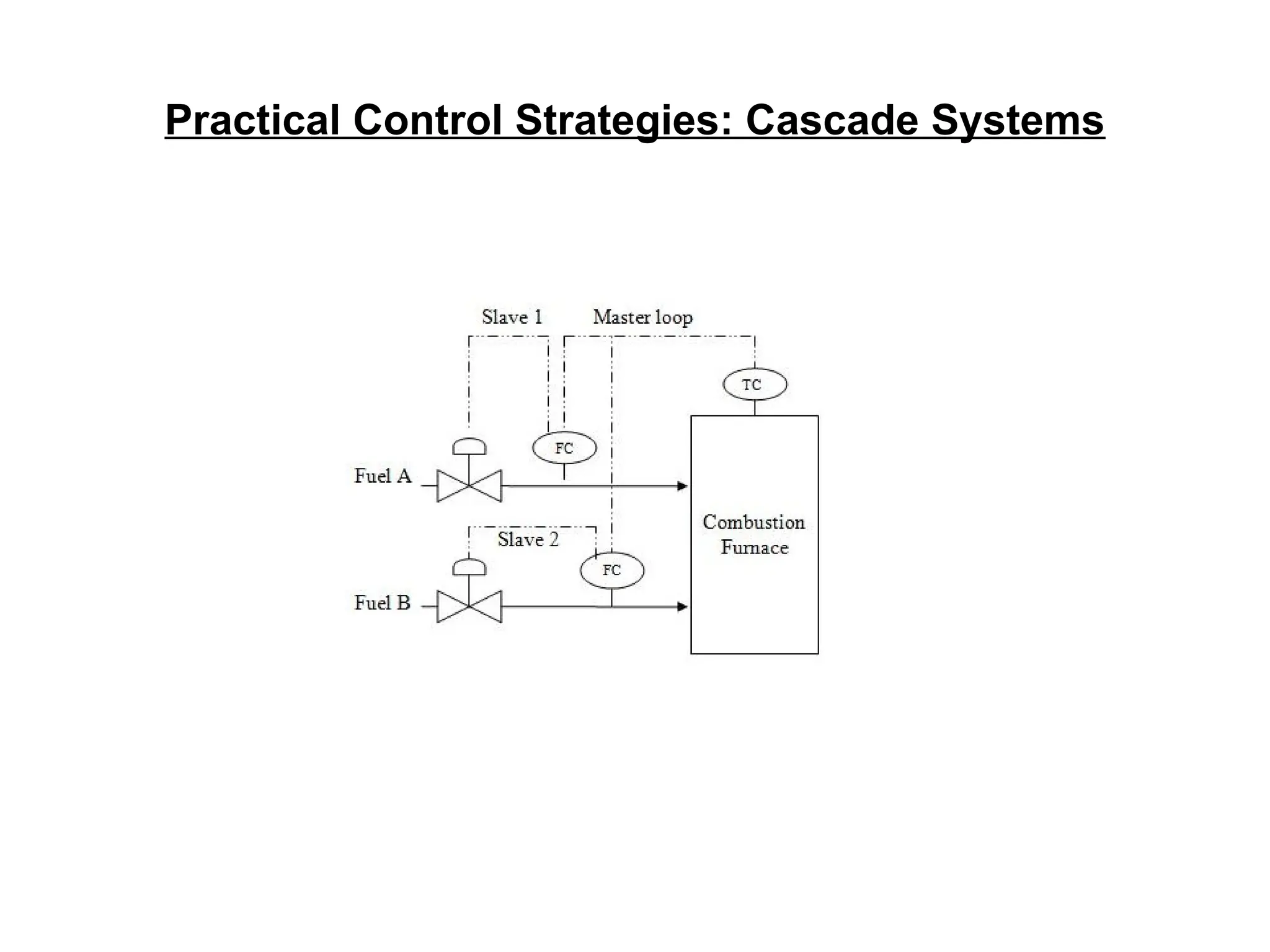

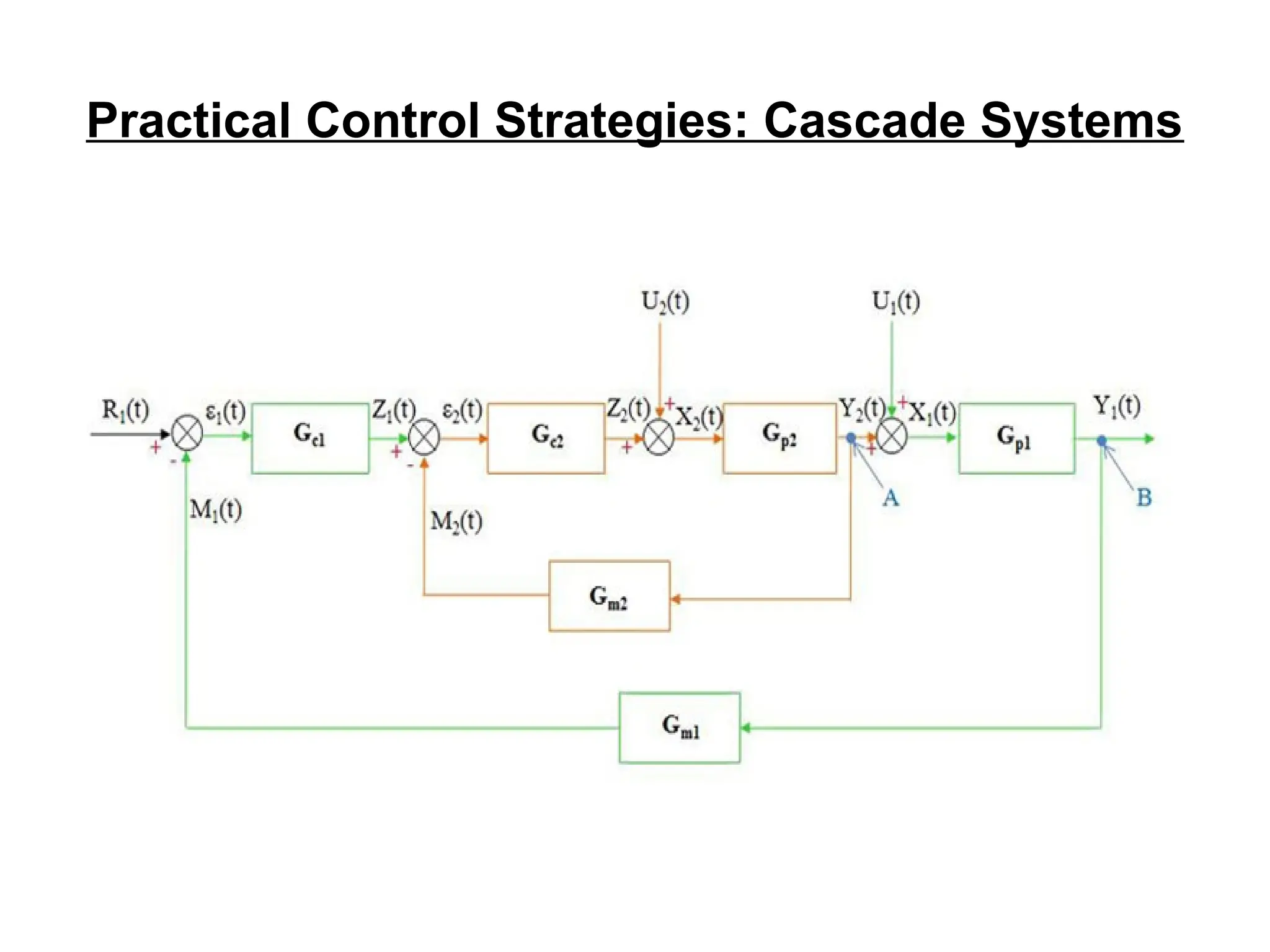

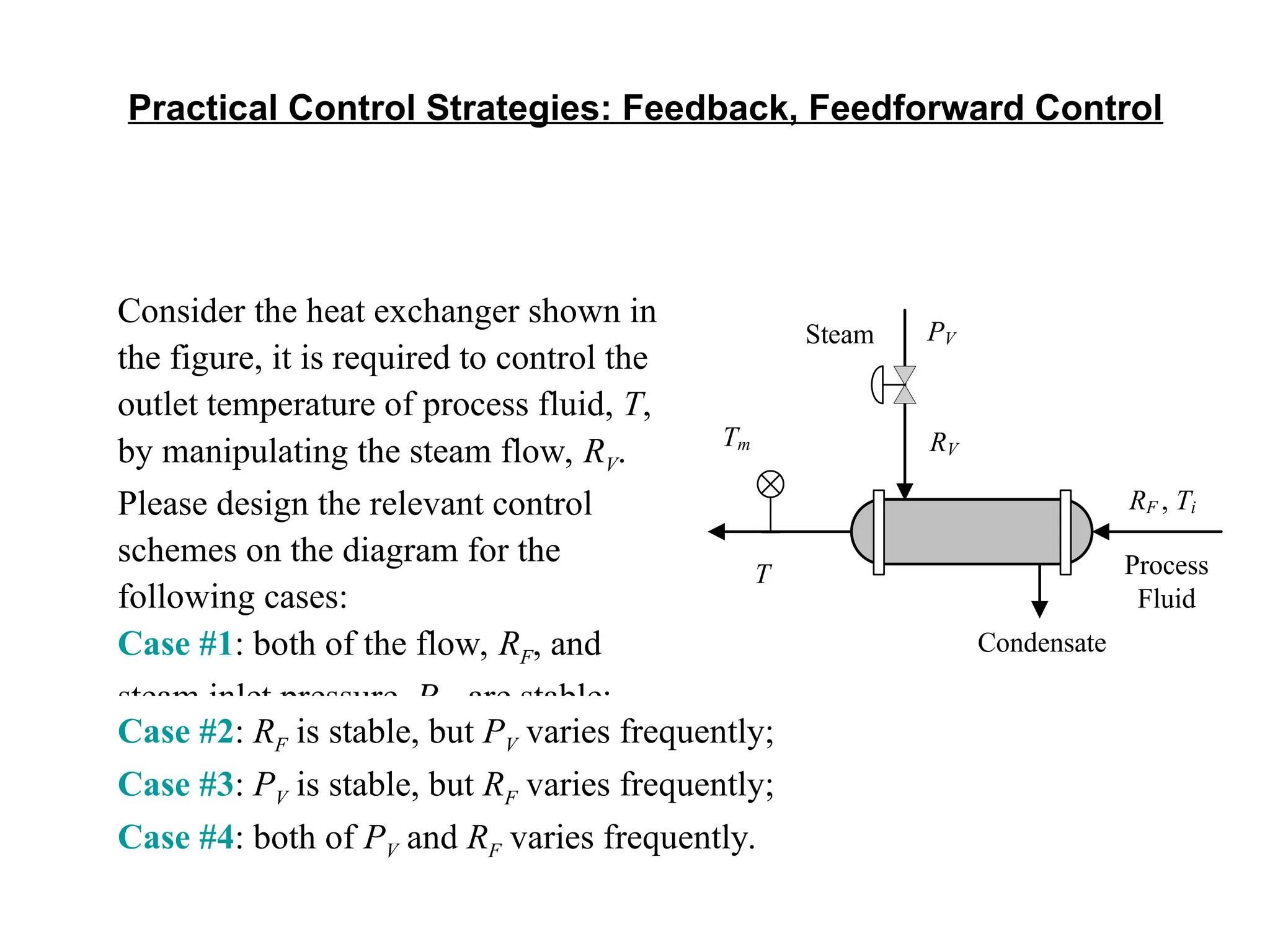

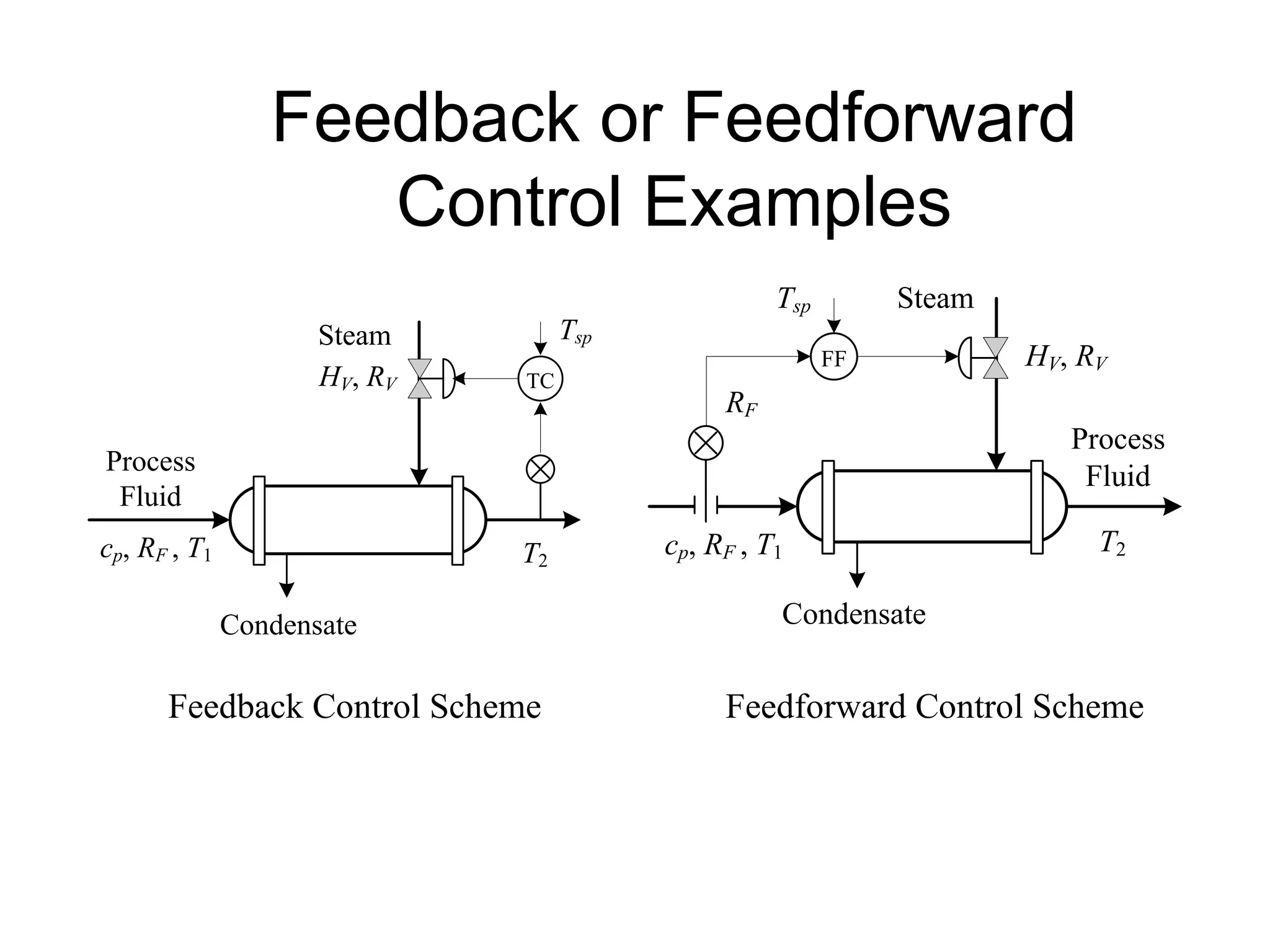

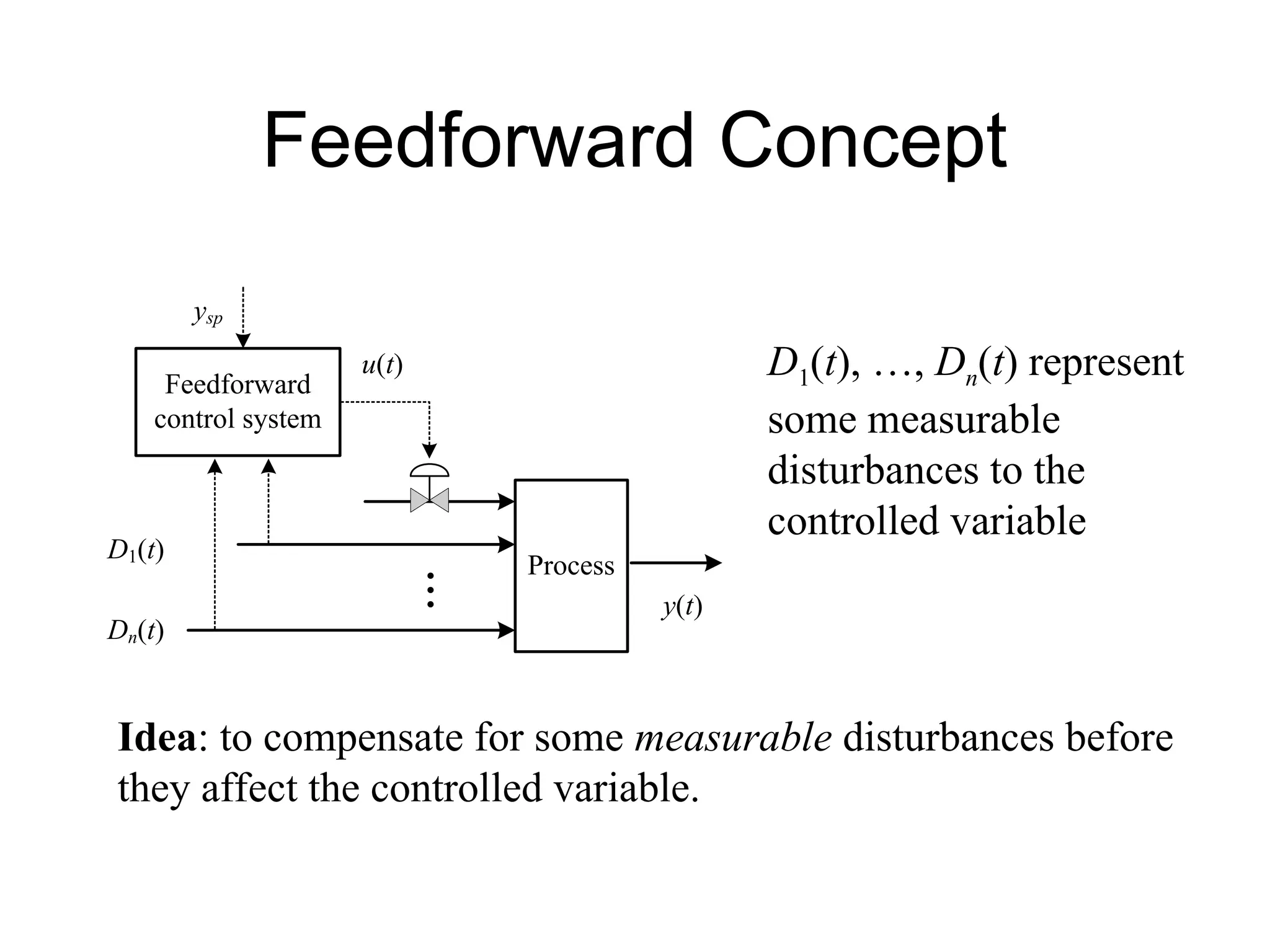

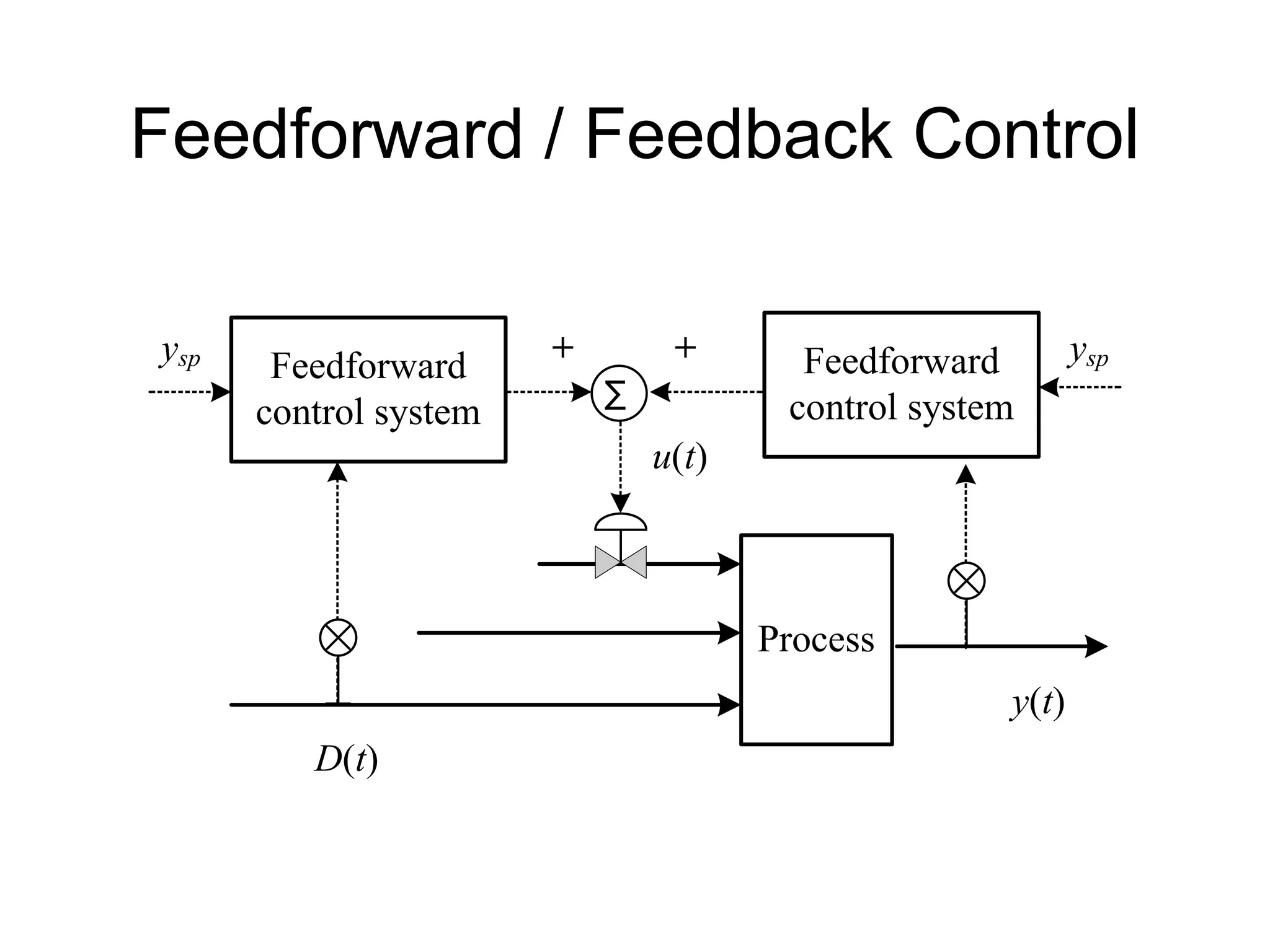

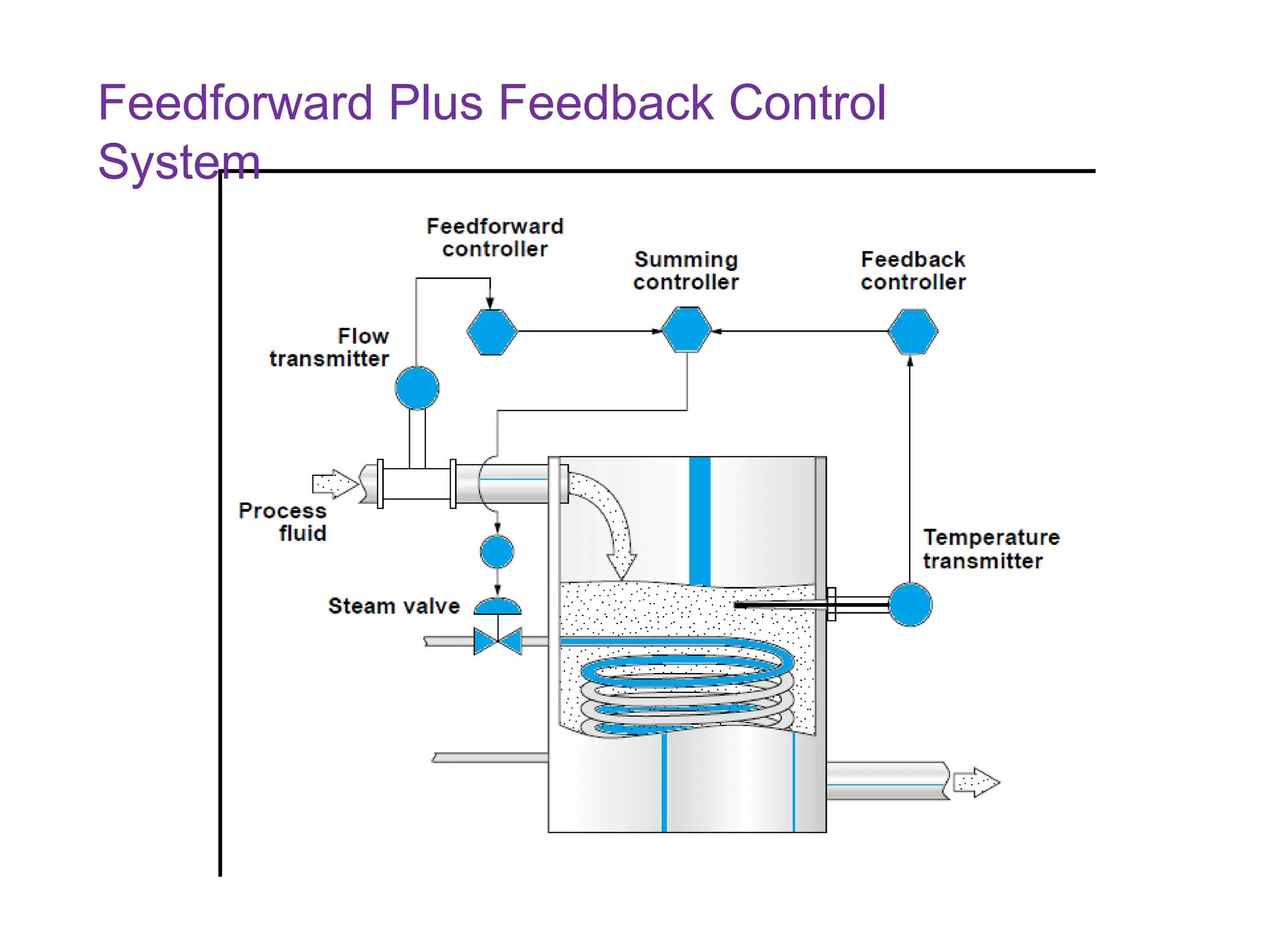

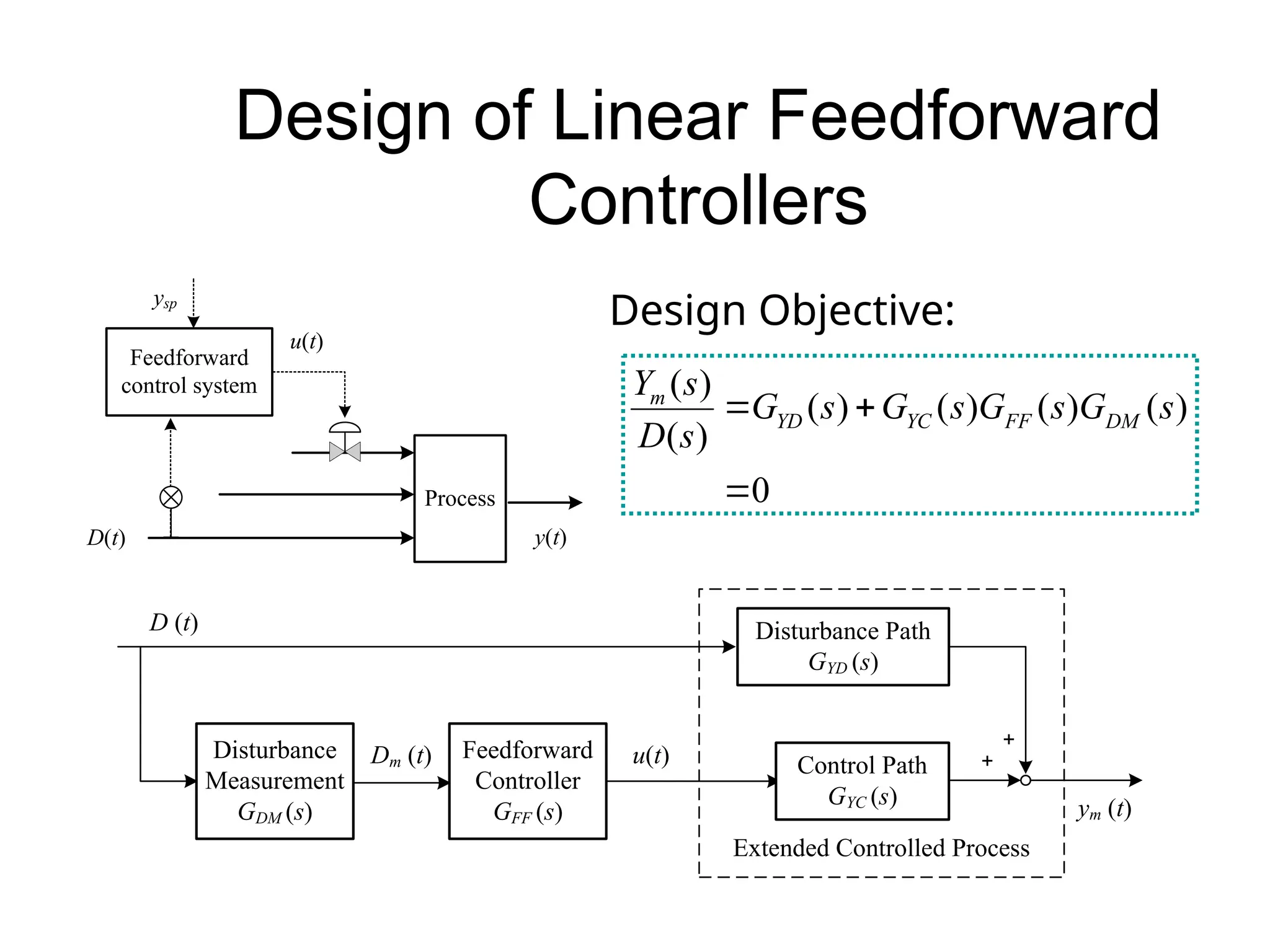

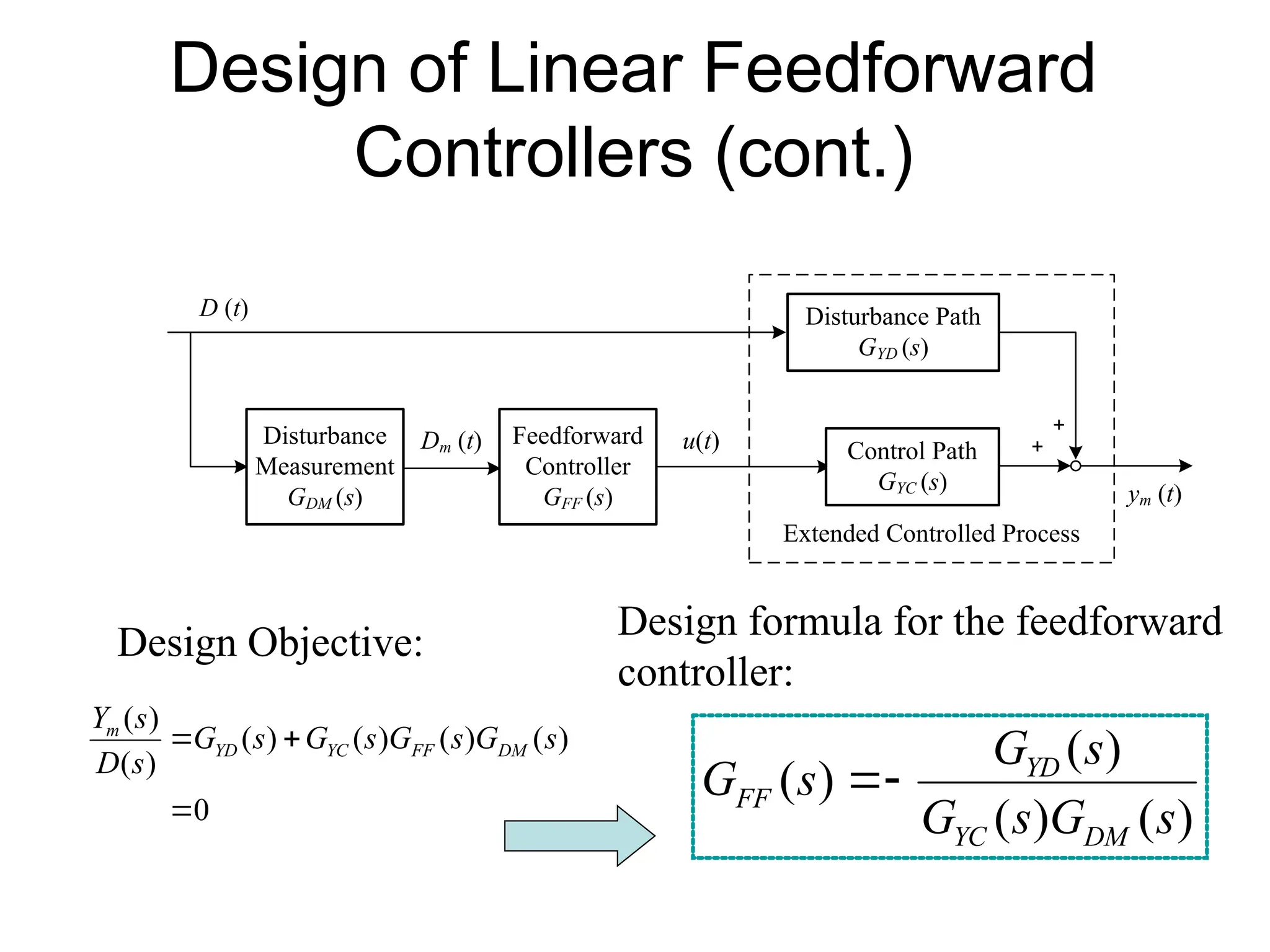

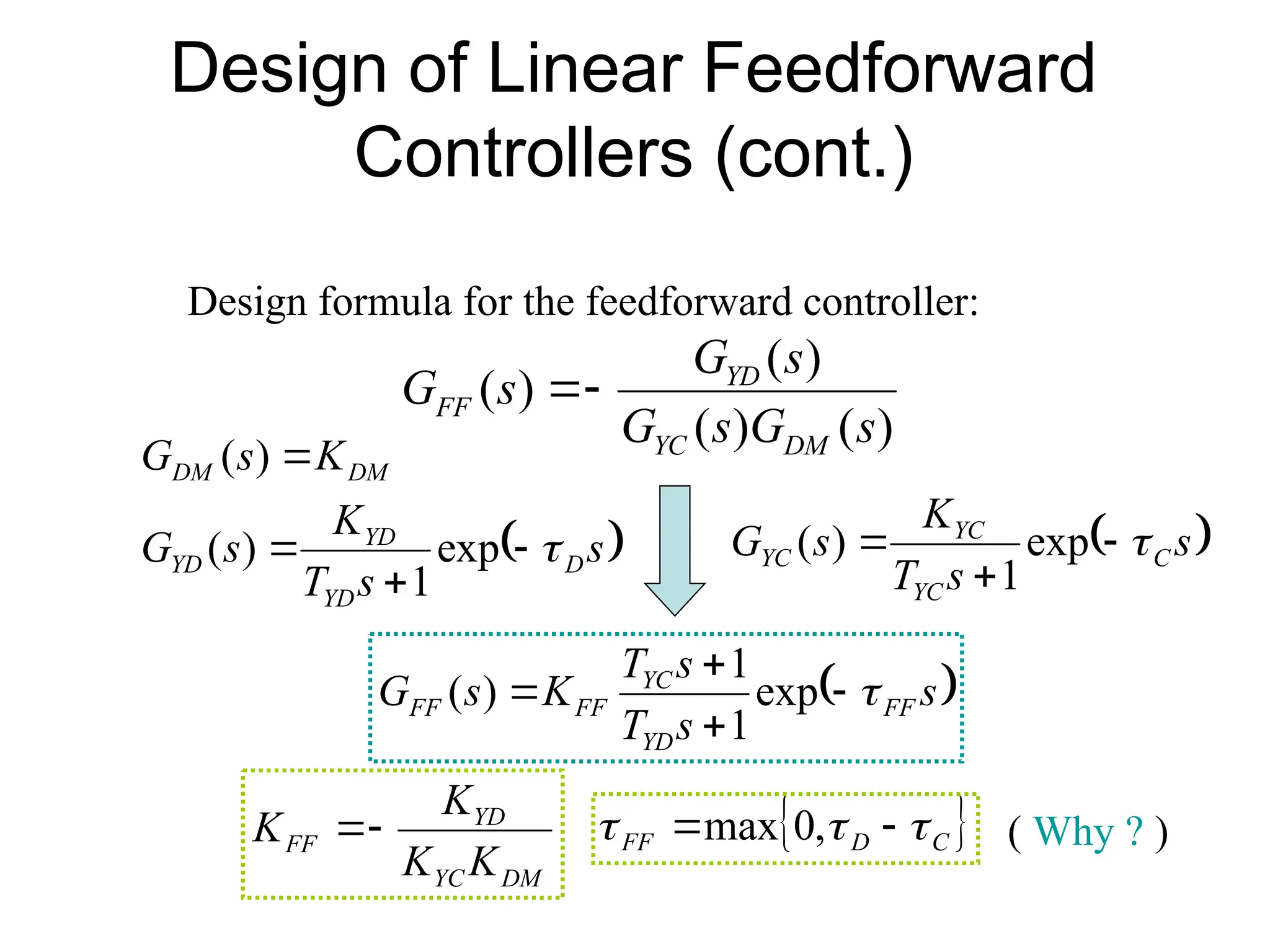

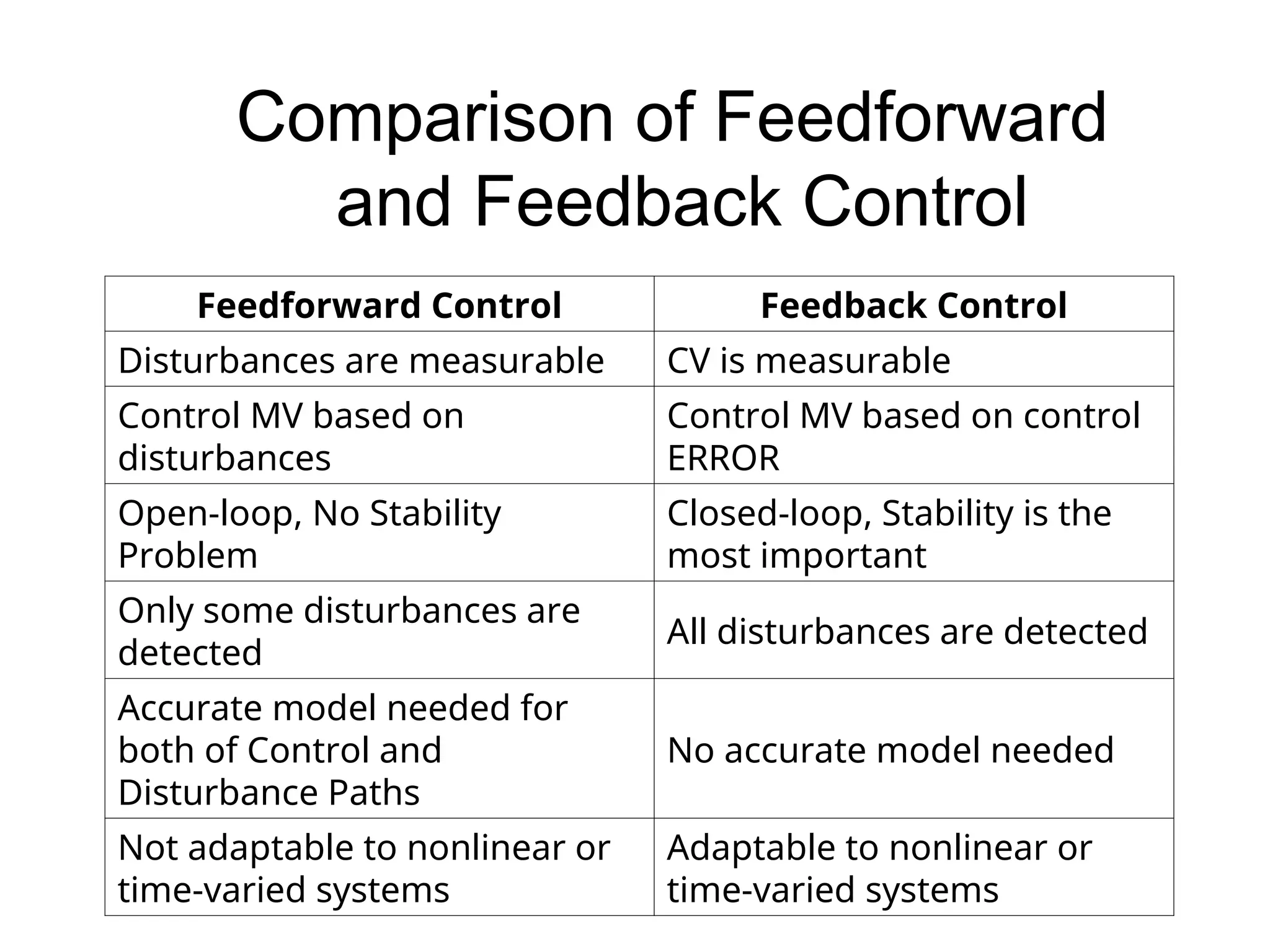

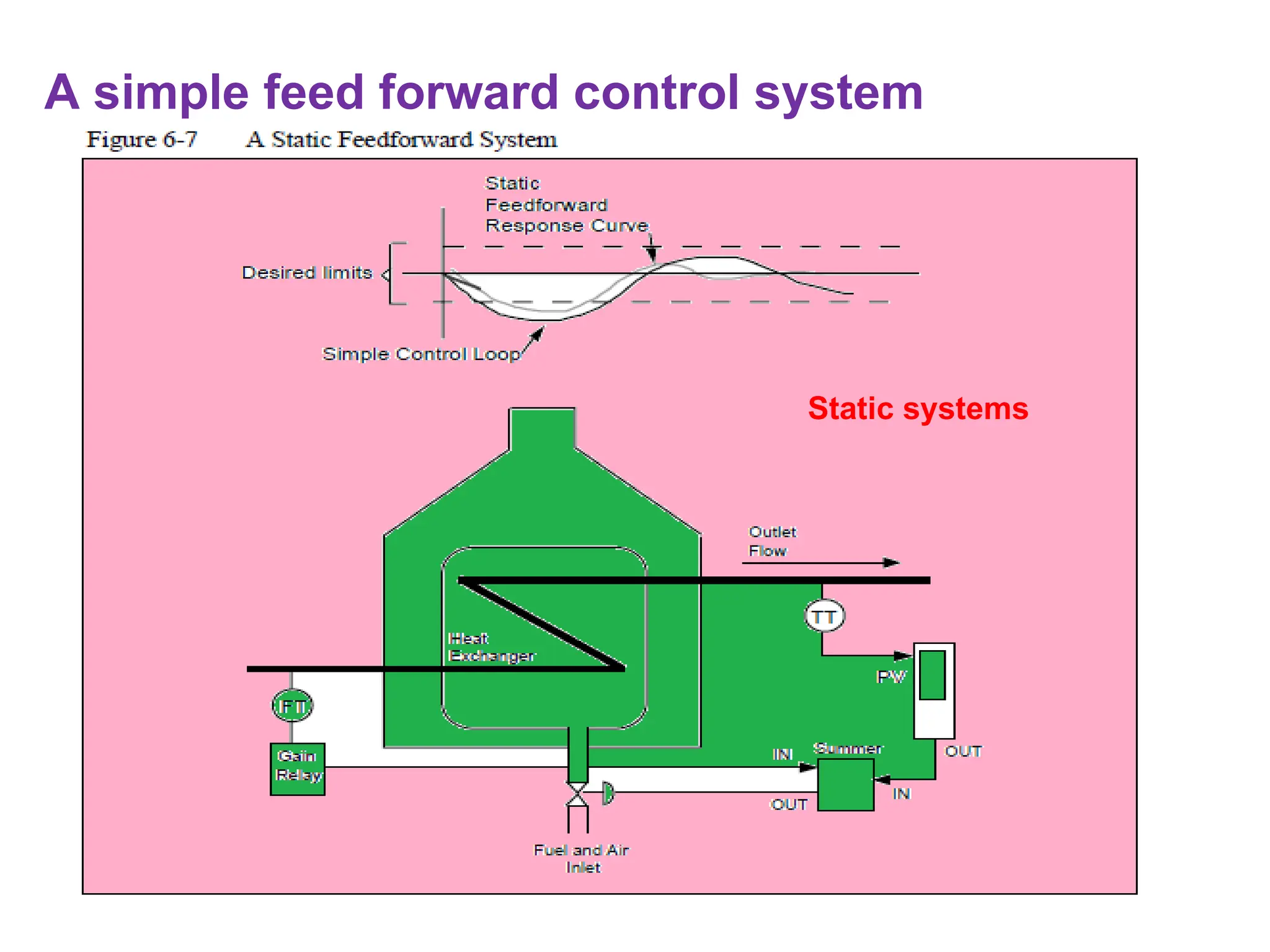

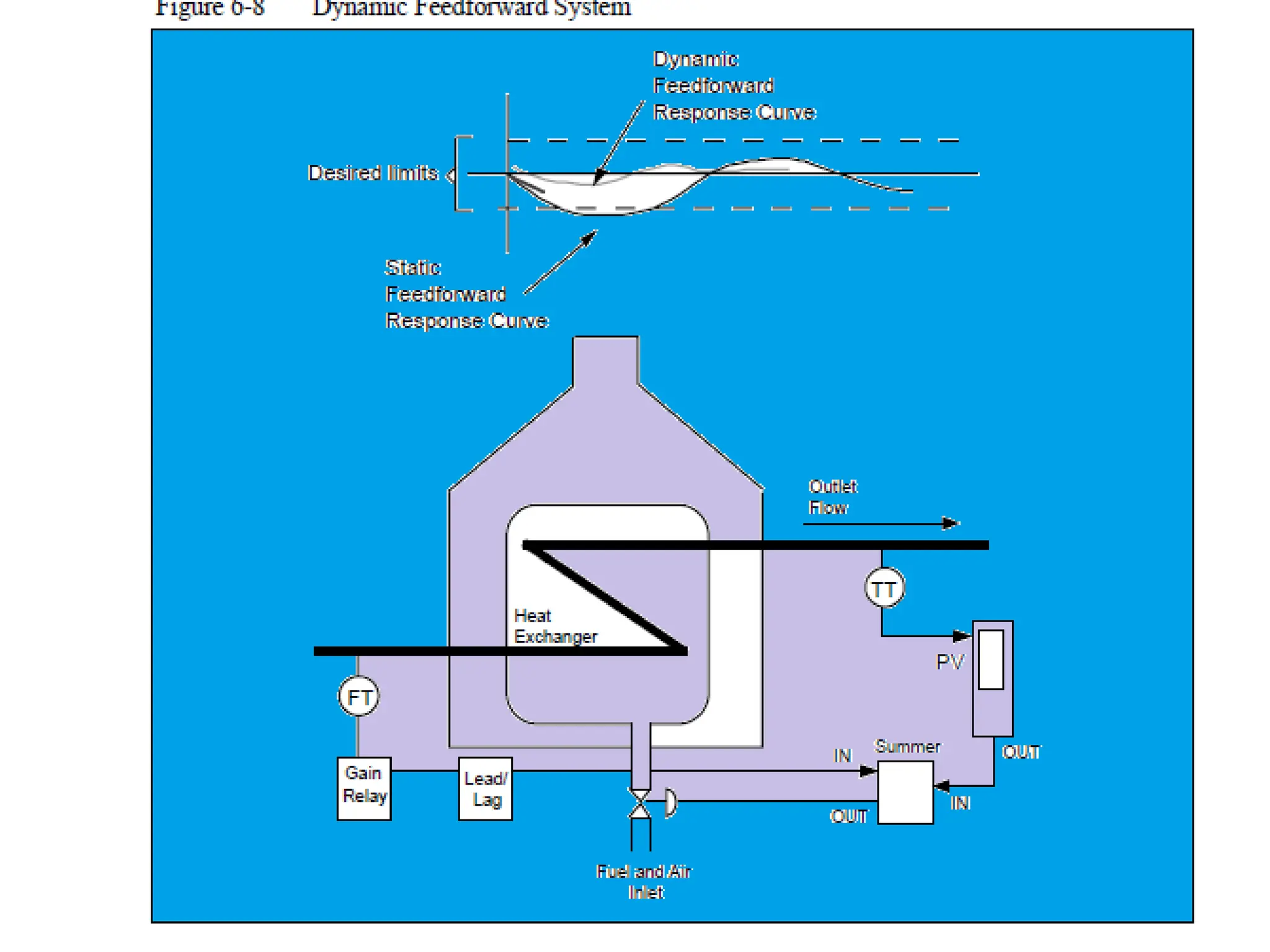

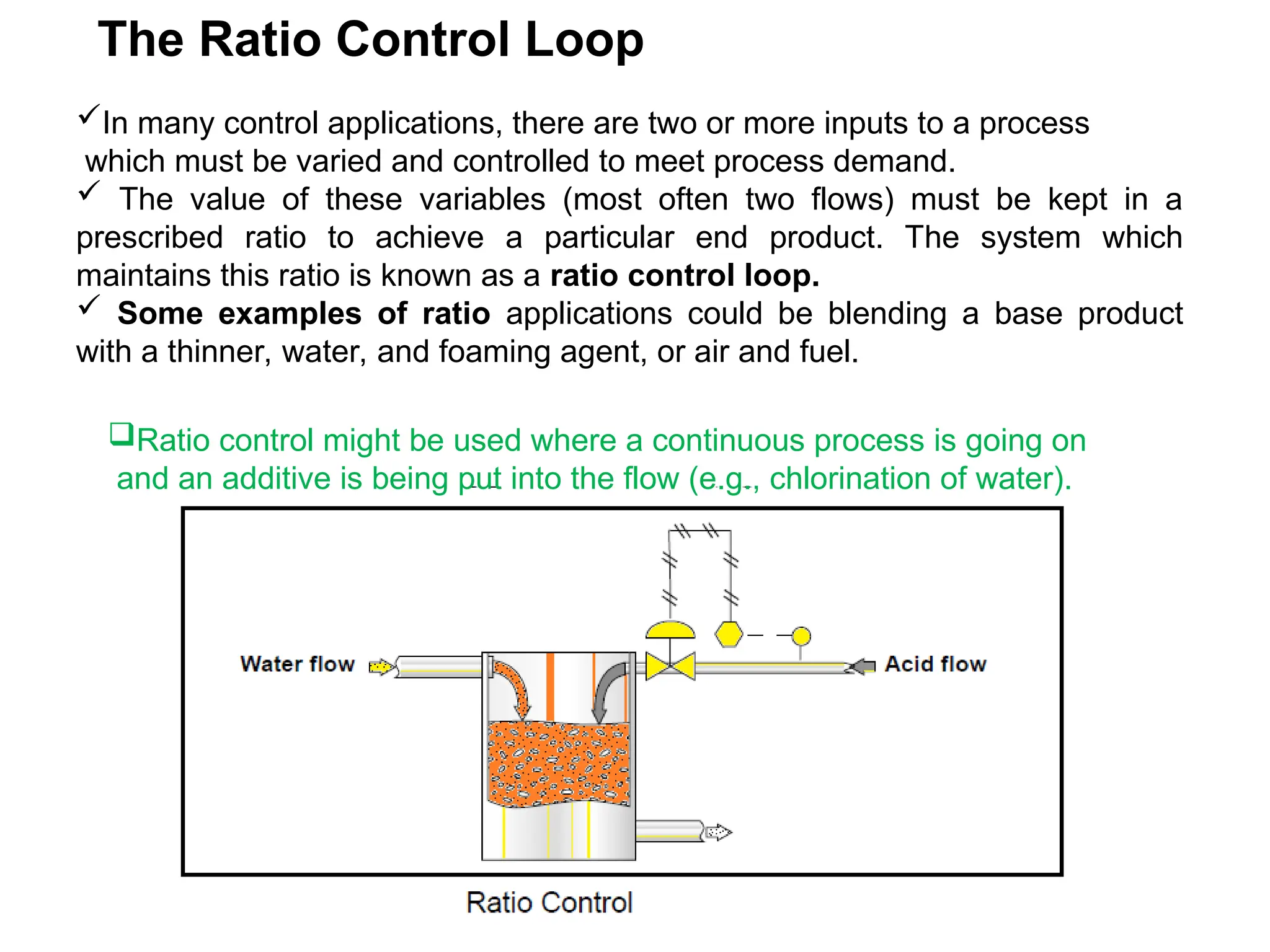

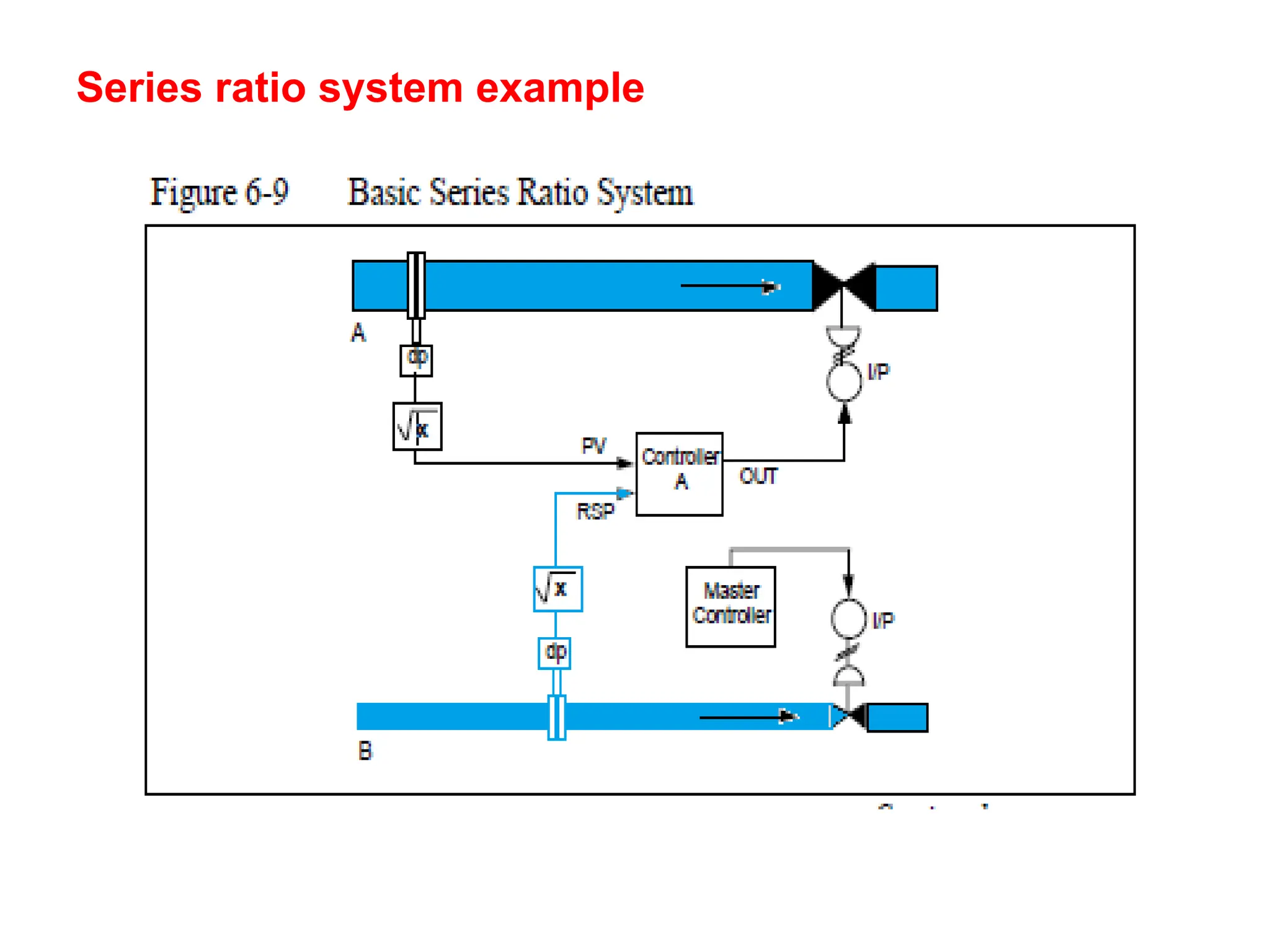

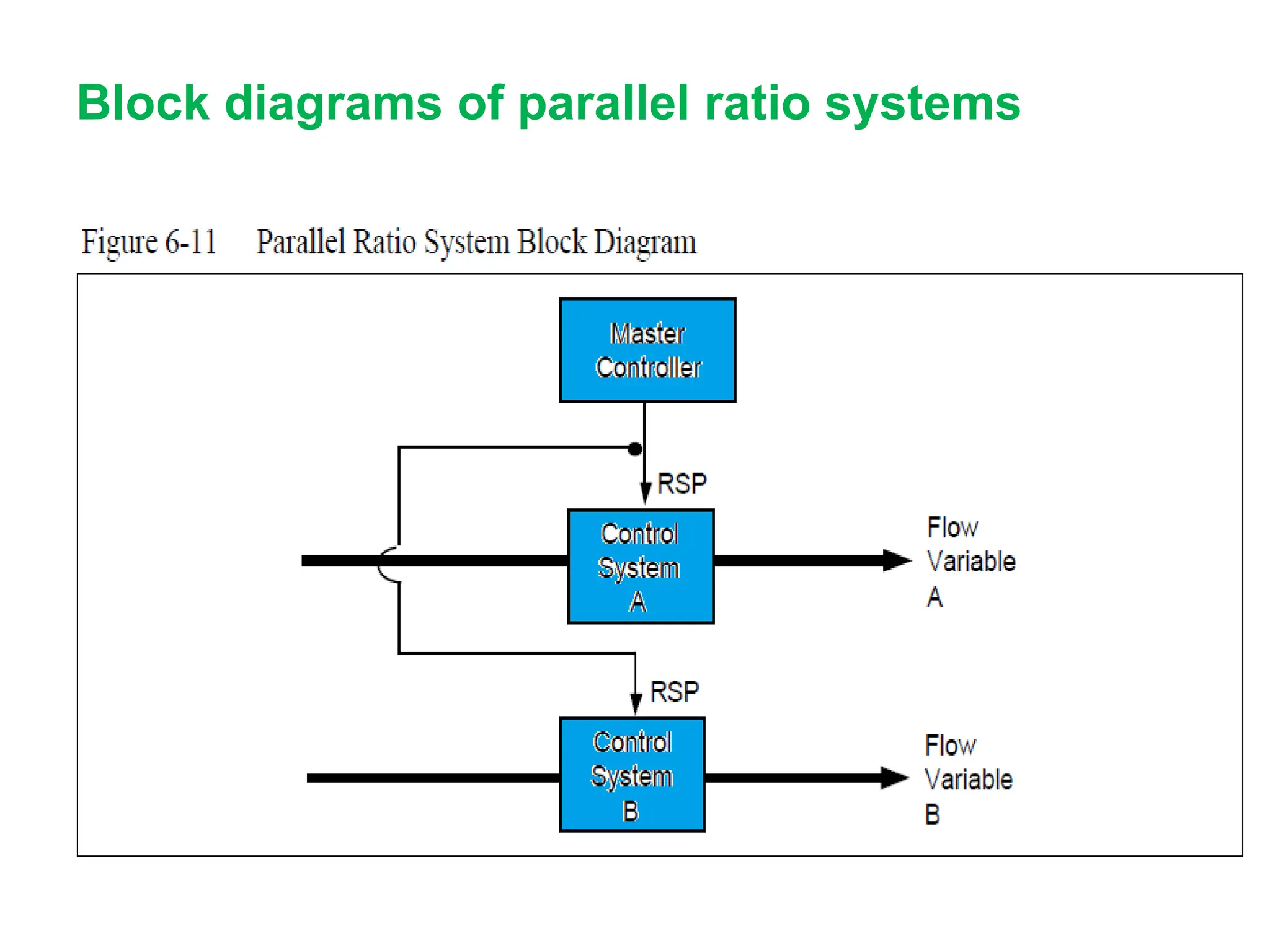

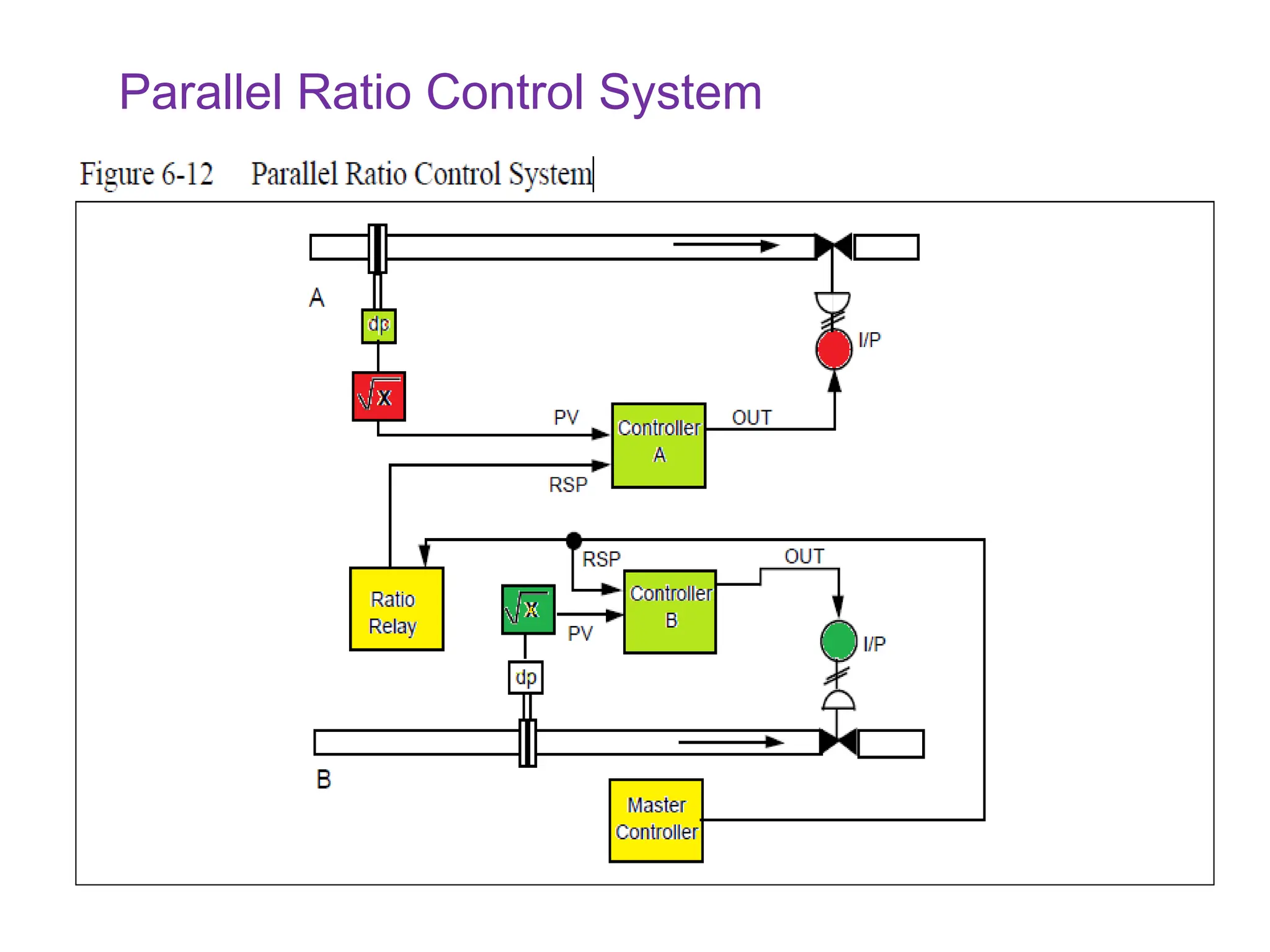

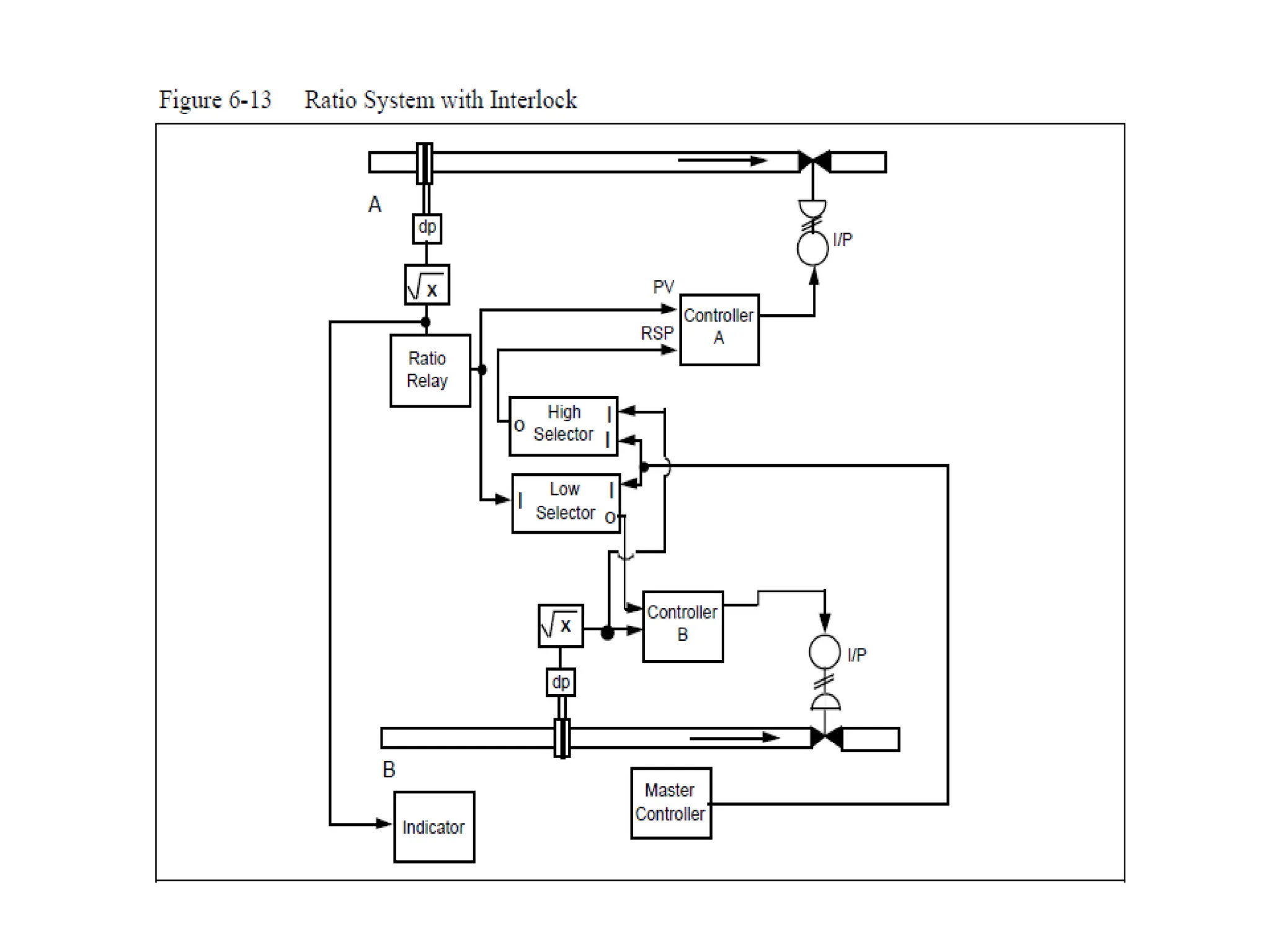

The document outlines the fundamentals of process control, highlighting various practical control strategies such as cascade, ratio, dead time, feedforward, and feedback control. It delves into the structure and advantages of cascade control systems, which utilize a primary loop to monitor a controlled variable and a secondary loop for adjusting disturbances, substantially improving system responsiveness and stability. Additionally, the document discusses the design considerations and the importance of choosing appropriate secondary variables for effective cascade control, as well as the benefits and limitations of different control approaches.