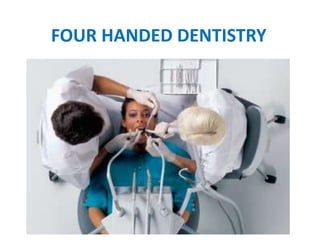

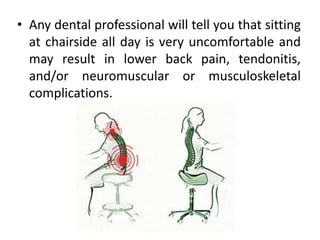

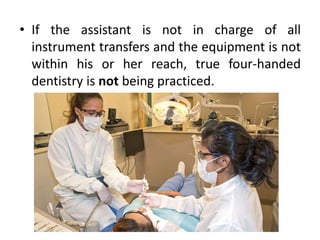

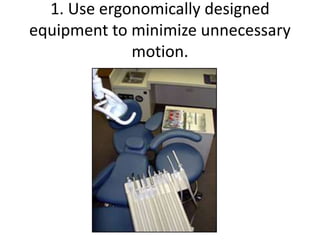

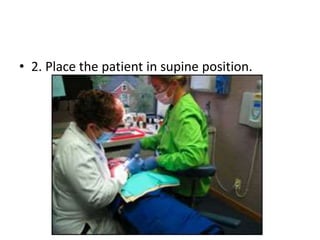

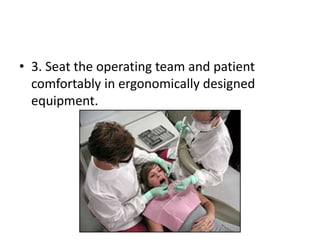

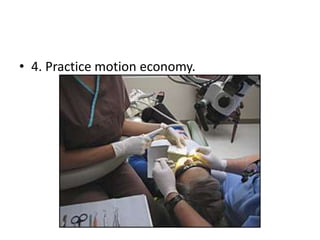

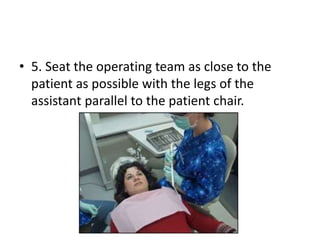

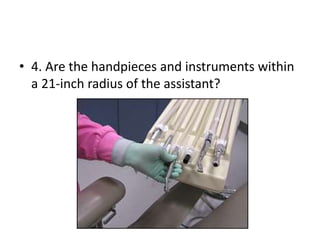

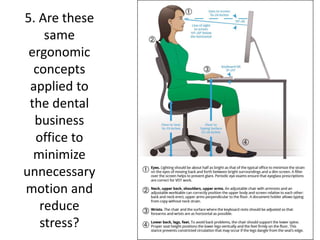

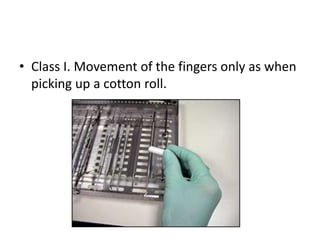

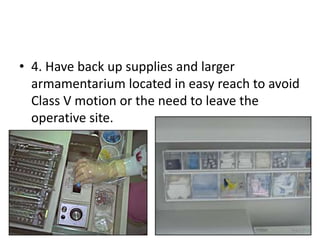

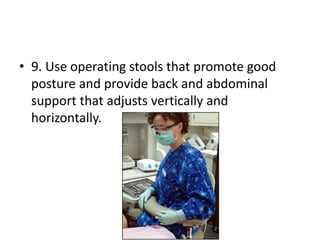

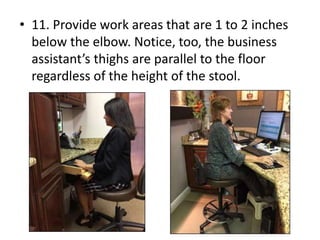

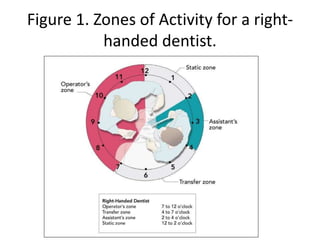

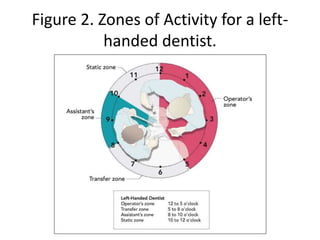

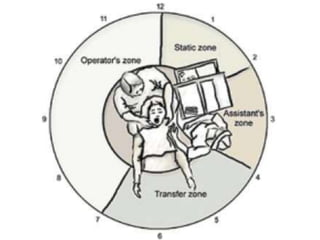

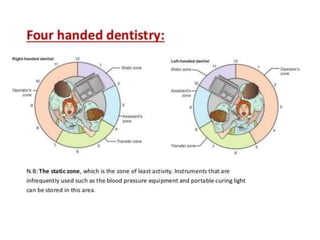

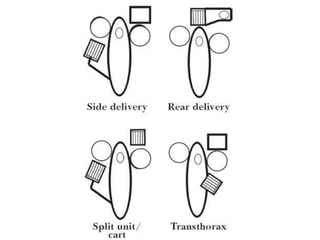

Four-handed dentistry involves the dental assistant assisting the dentist by handling instruments and equipment to reduce strain on the dentist and increase efficiency. It is based on principles like minimizing unnecessary motions, positioning equipment ergonomically, and having the assistant and dentist work closely together in designated zones. Following concepts such as four-handed dentistry can help reduce strain, improve productivity, and make the dental team more comfortable.