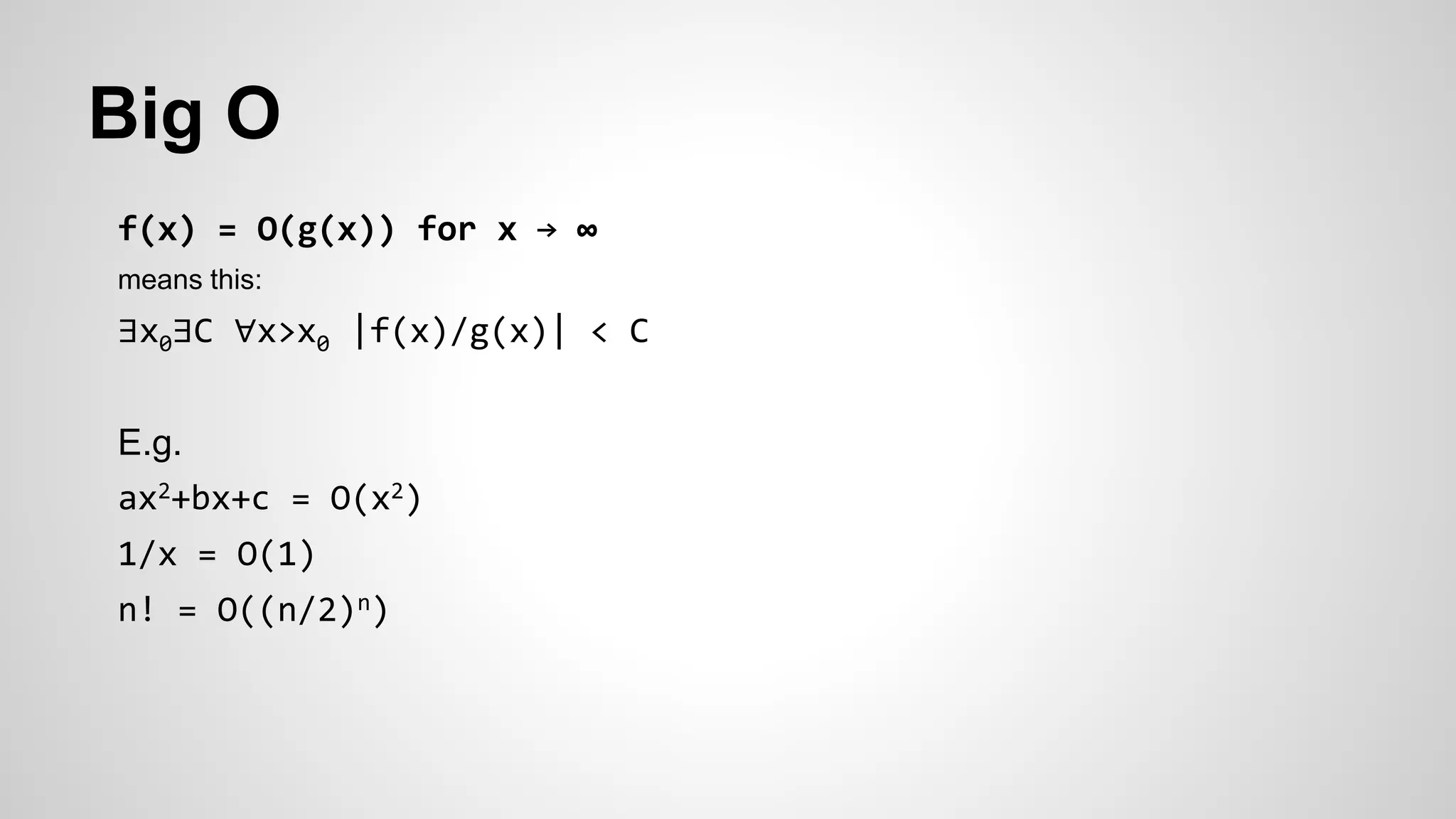

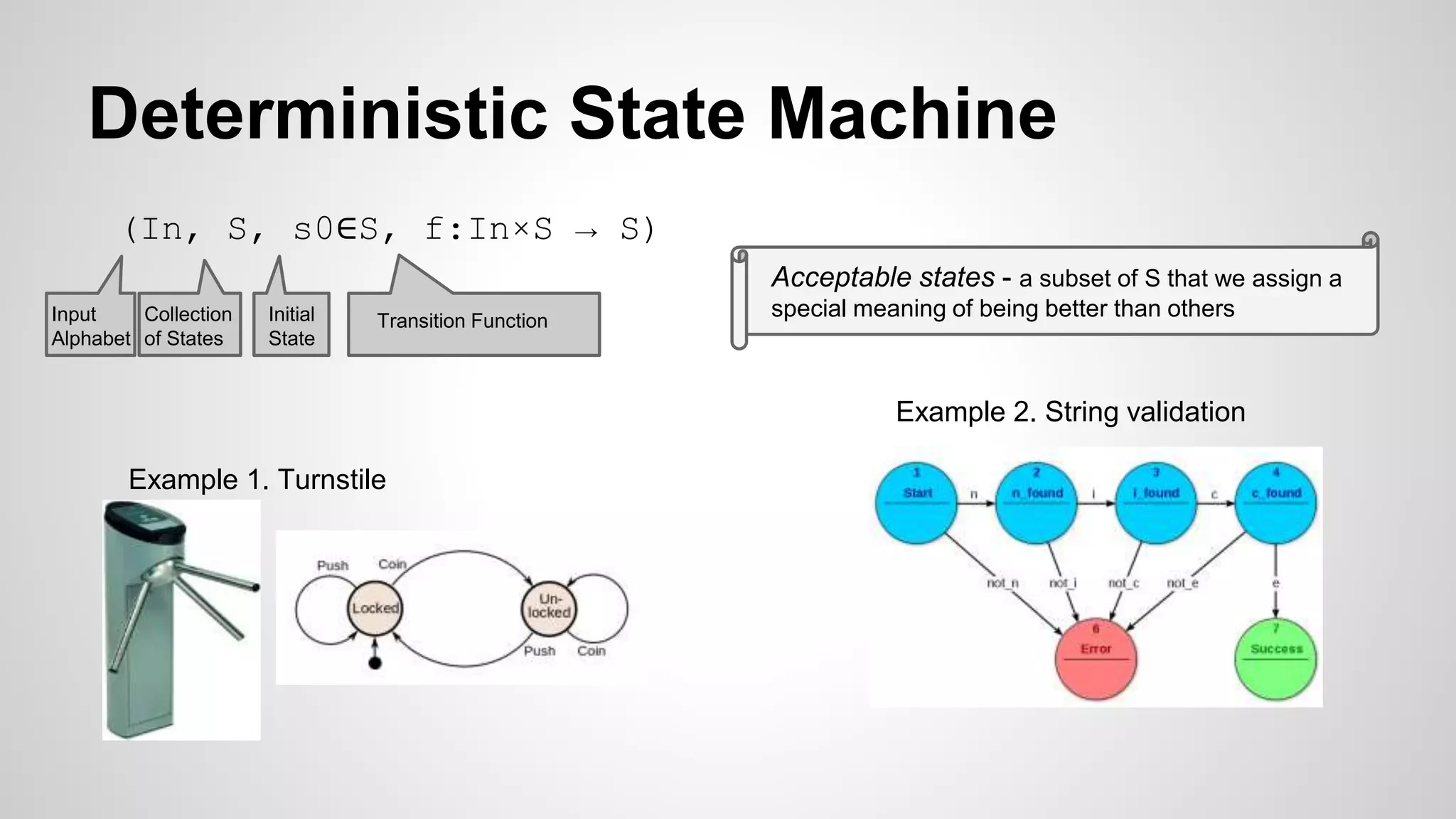

The document discusses formal methods in software, focusing on deterministic and nondeterministic finite state machines (FSMs), their definitions, and examples. It introduces the concepts of transitions, acceptable states, and the relationship between regular languages and FSMs, including how to construct regular languages and grammars. Additionally, it covers the complexities of parsing regular expressions and various illustrative examples and references.

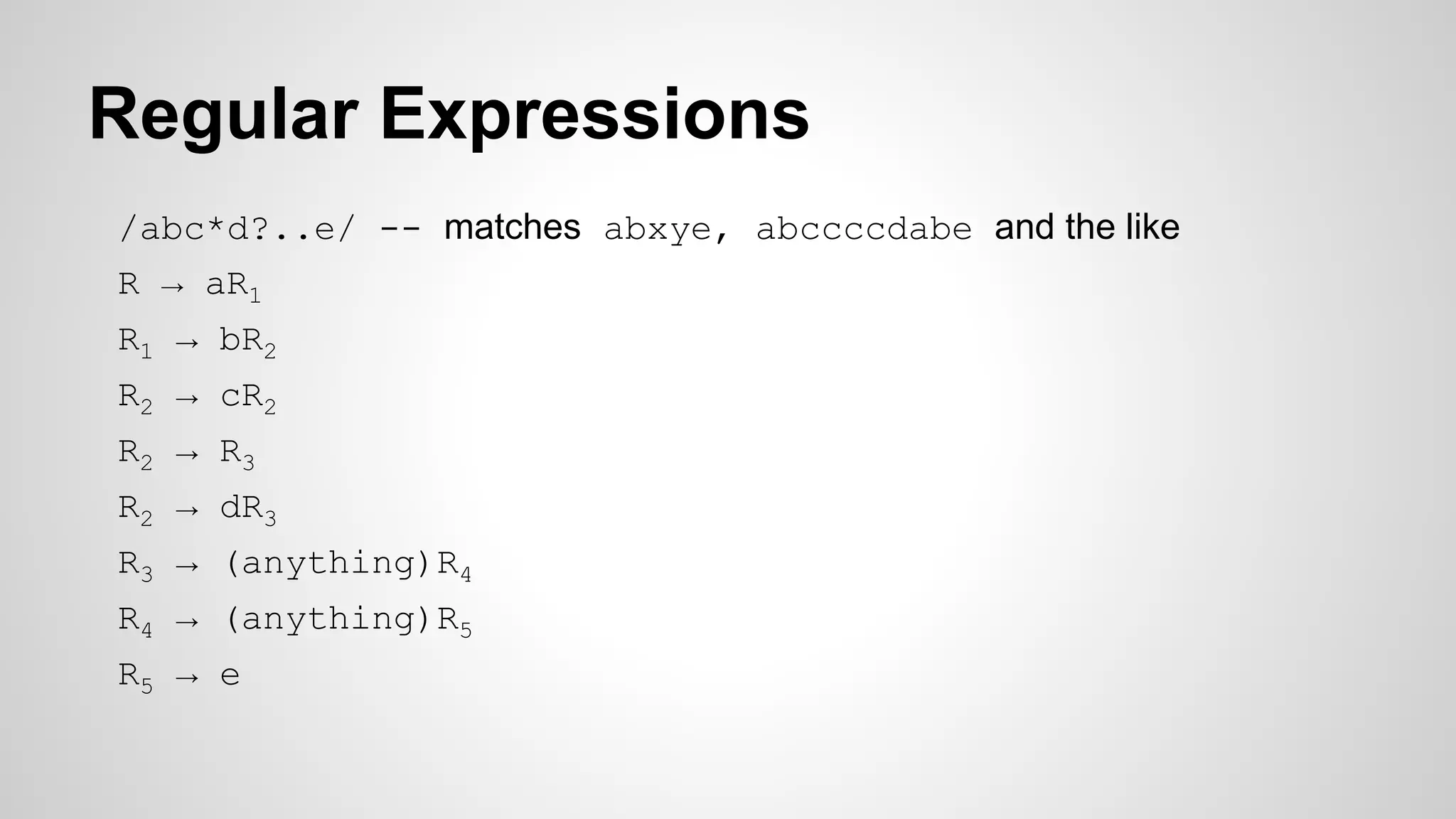

![Parsing Regular Expressions

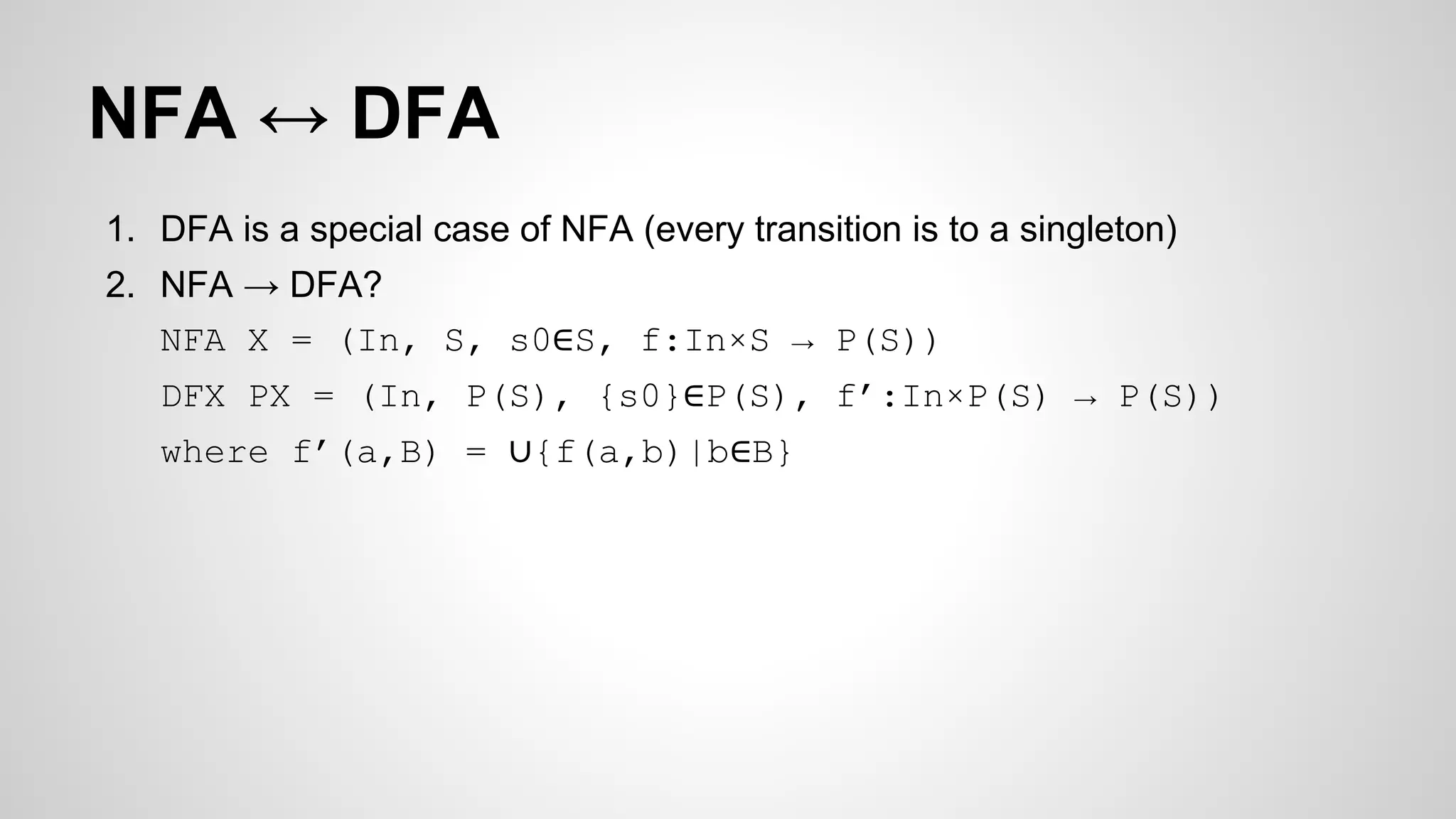

The problem with NFA - exponential time, O(2n). E.g. a?nan against an

Can transform to DFA;

then it’s linear,

O(n) (but may take space).

A simple example in Scala: https://gist.github.com/vpatryshev/3778294

The example is tricky: it’s not an FSM; it uses call stack.

main(int c,char**v){return!m(v[1],v[2]);}m(char*s,char*t){return*t-42?*s?63==*t|*s==*t&&m(s+1,t+1):!*t:m(s,t+1)||*s&&m(s+1,t);}](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/formalmethods-2-languagesandmachines-140401210012-phpapp01/75/Formal-methods-2-languages-and-machines-15-2048.jpg)