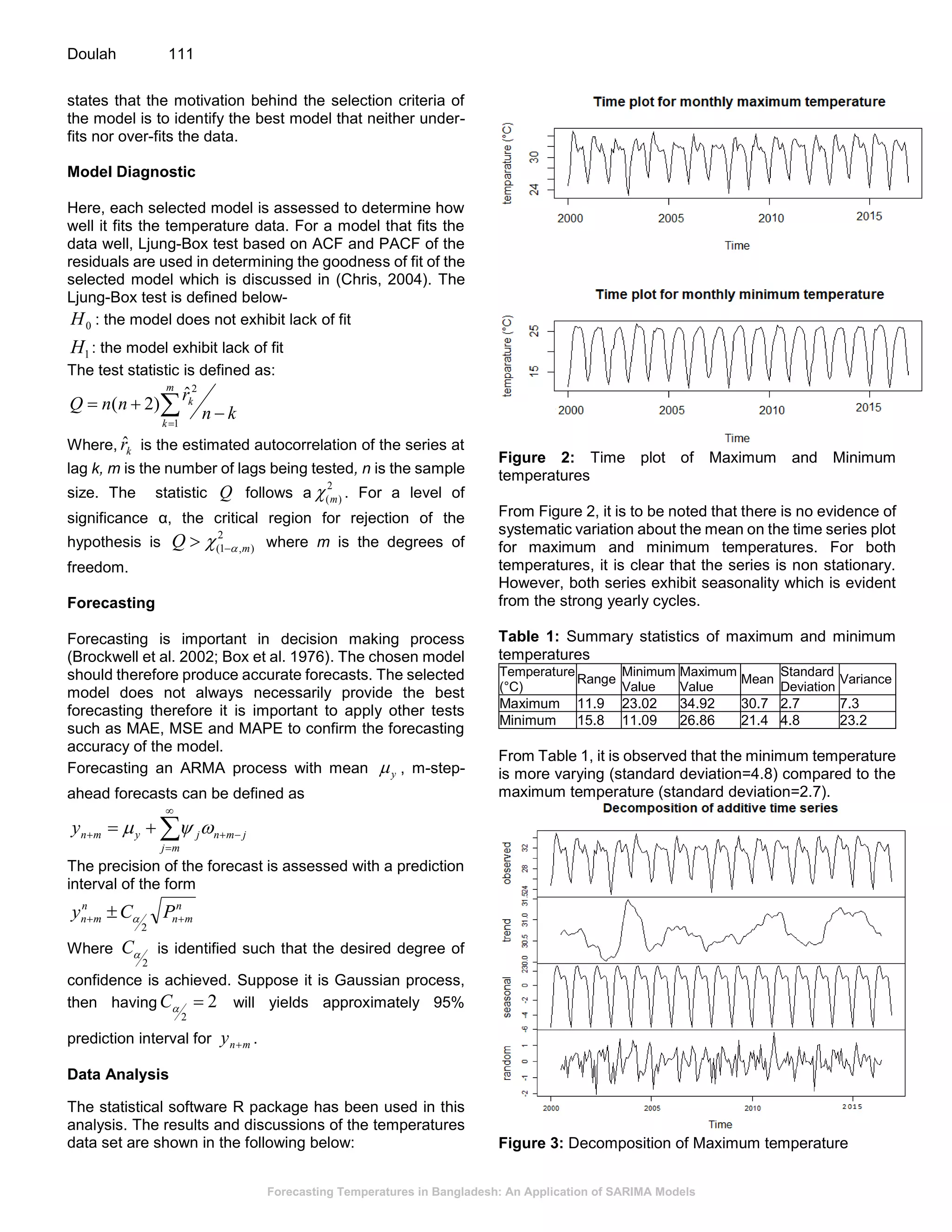

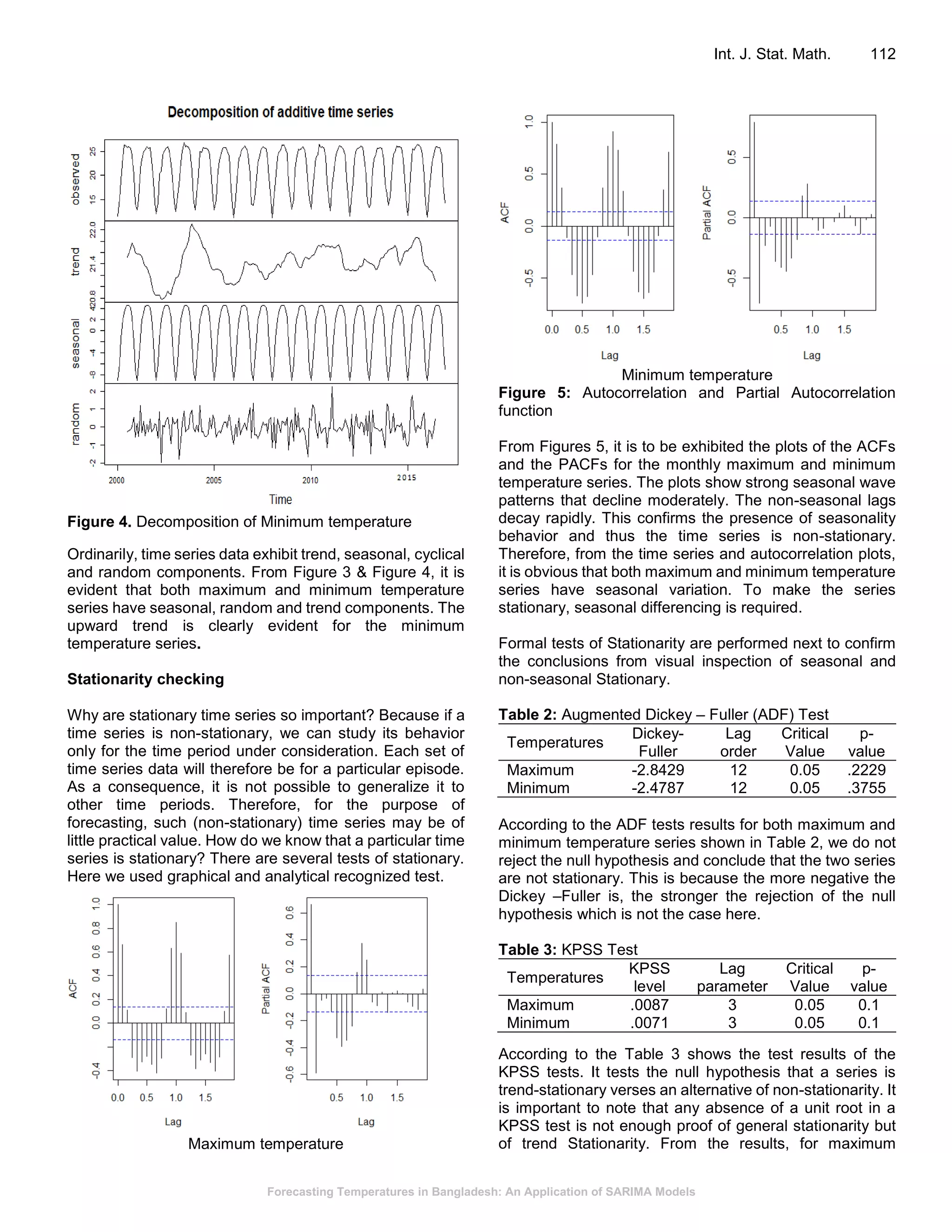

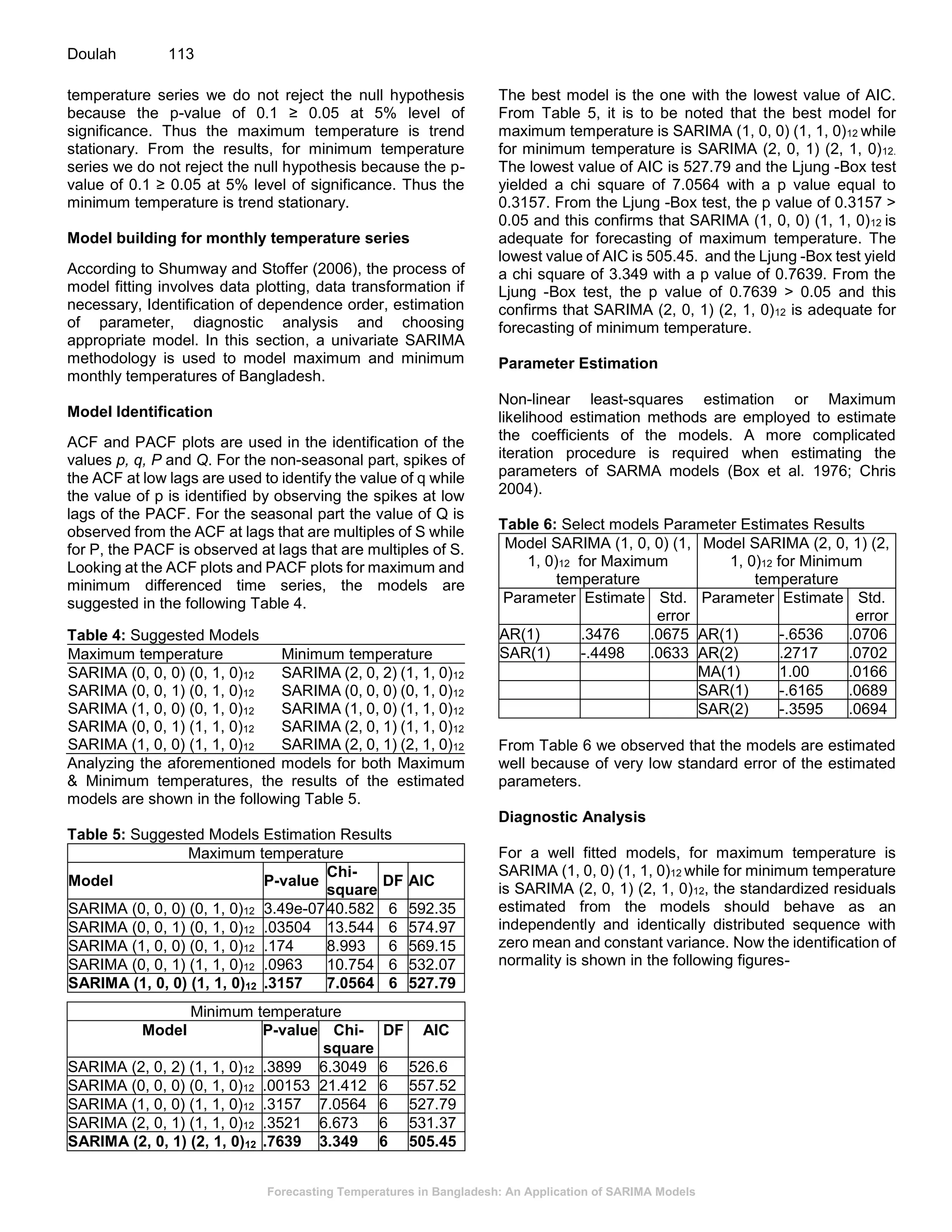

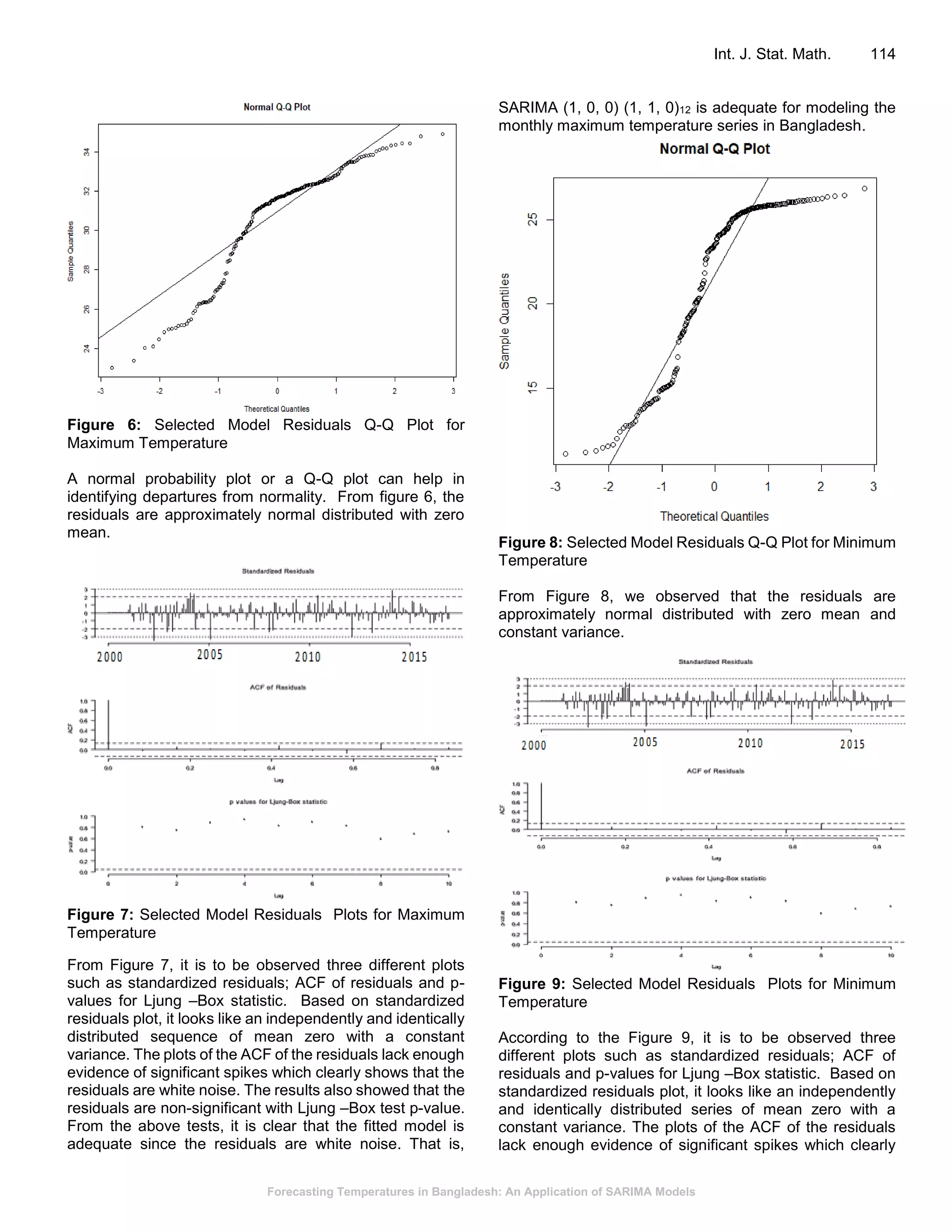

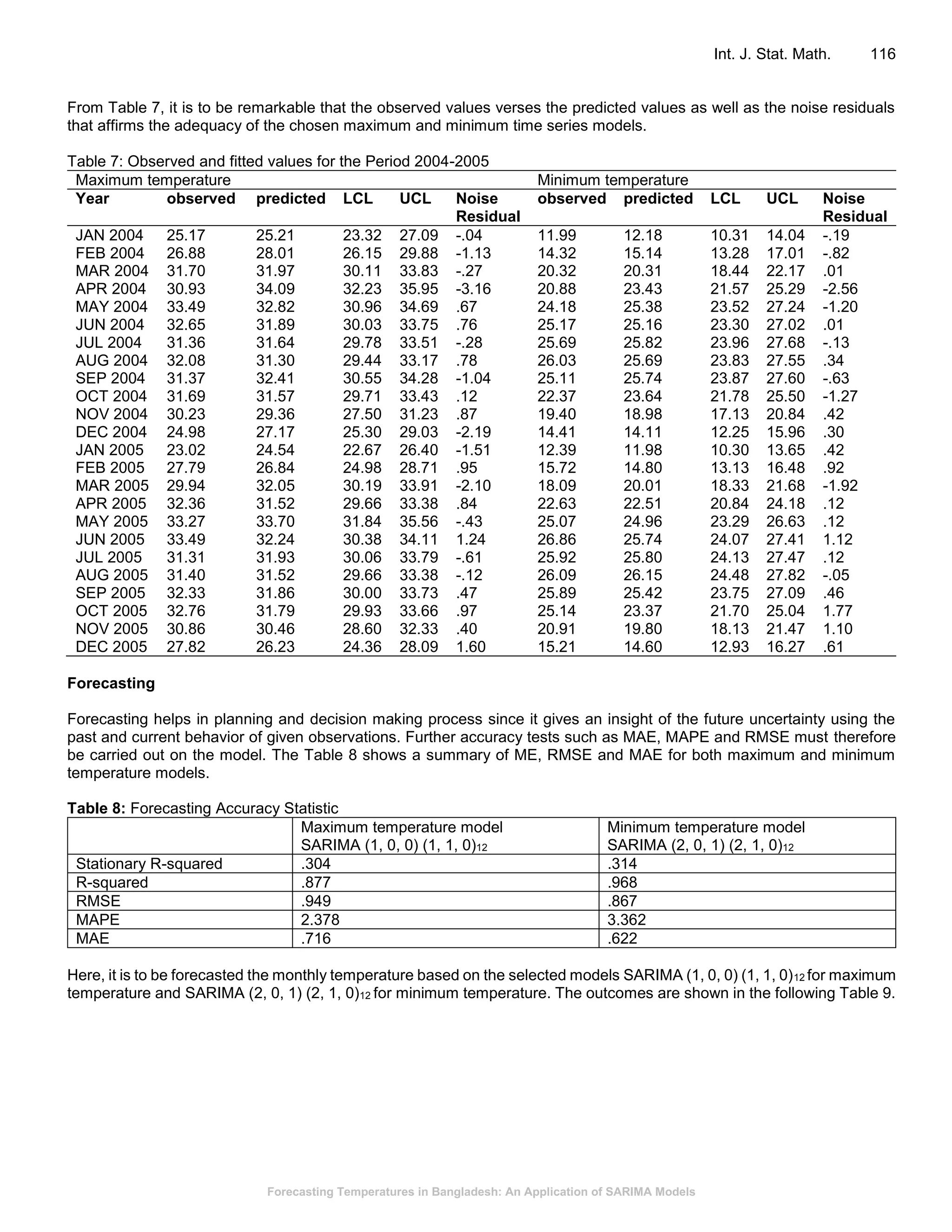

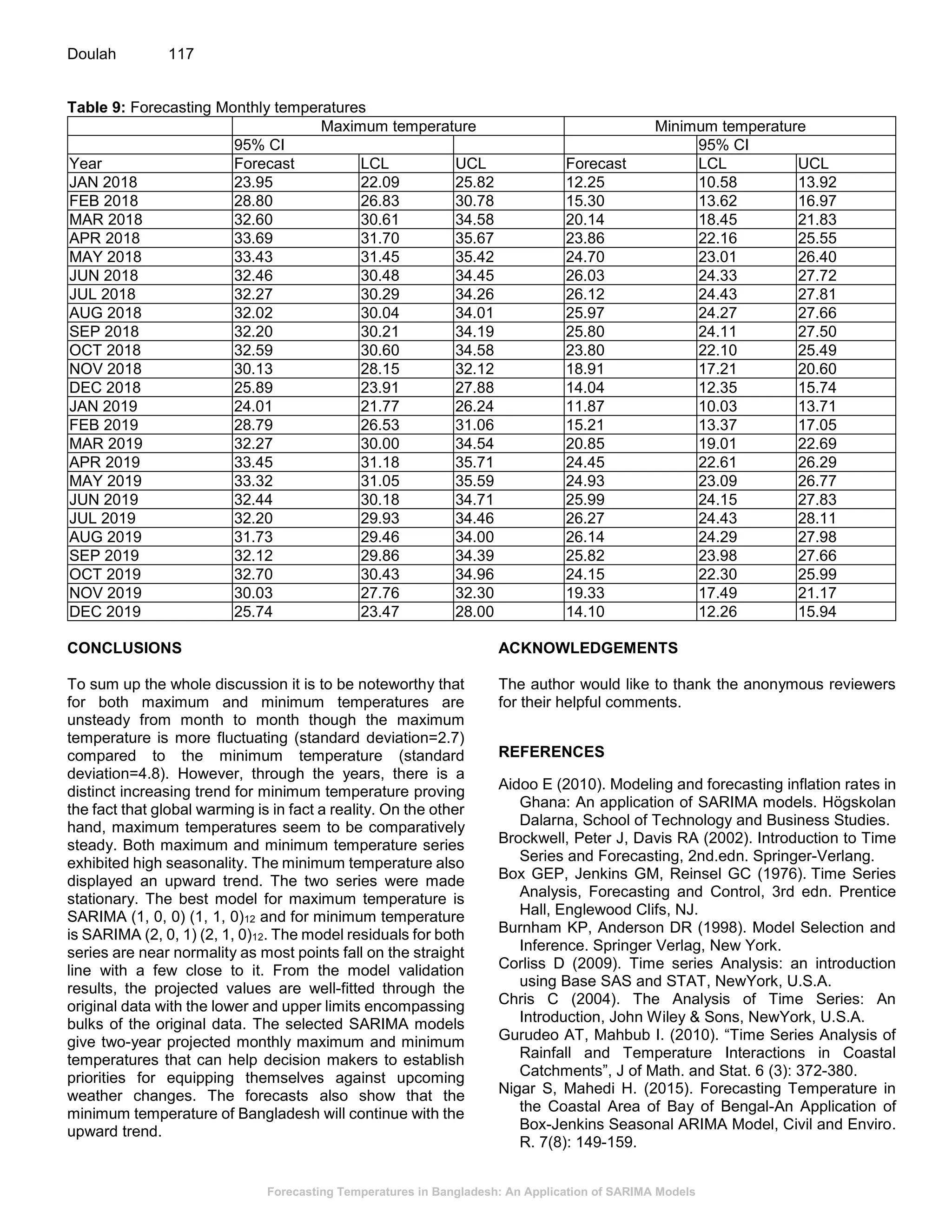

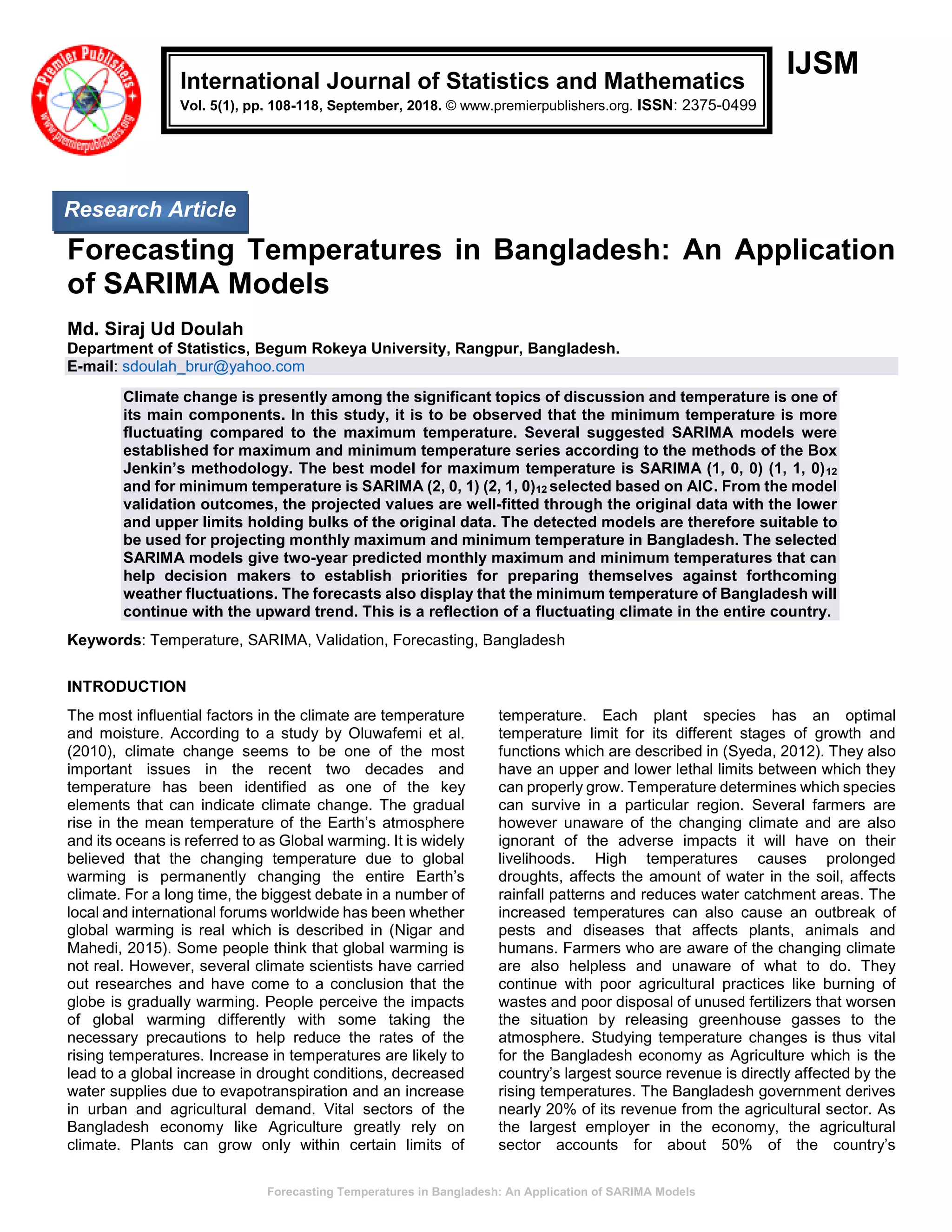

This document presents a study on forecasting temperatures in Bangladesh using SARIMA models, highlighting the significant fluctuations in minimum temperatures compared to maximum temperatures. The best models identified for maximum and minimum temperatures are SARIMA(1, 0, 0)(1, 1, 0)12 and SARIMA(2, 0, 1)(2, 1, 0)12, respectively, with validation showing accurate fitting to original data. The forecasts predict an upward trend in minimum temperatures, indicating the necessity for climate-related planning in sectors such as agriculture, which is vital for the Bangladeshi economy.

![Forecasting Temperatures in Bangladesh: An Application of SARIMA Models

Doulah 109

employment. In addition, more than 70% of Bangladesh

population living in rural areas depends on agricultural

related activities for their daily livelihoods. Climatic studies

on temperature are therefore vital for the survival of the

agricultural sector as the key source of revenue to the

government of Bangladesh.

Temperature is one of the key elements of climate and it is

important to various sectors of the economy like

Agriculture. Temperature affects water sources, pests that

attack plants, animals and human diseases. Despite the

increasing climate changes, majority of Bangladeshi

citizens are still not well informed. Analyzing and

forecasting of temperature changes will thus help various

stakeholders and government to plan in advance in order

to counter climate related disasters. The objective of this

research is to build a time series model and use this model

to analyze and forecast the variation in maximum and

minimum temperature in Bangladesh in order to inform

stakeholders who depend directly or indirectly on it to plan

in advance.

METHODOLOGY

Average Maximum and Minimum Monthly temperature

data covering Bangladesh has been collected from the

Bangladesh Meteorological Department (BMD). This data

was recorded in monthly basis covering an 18 year period

from January 2000 to December 2017 (www.data.gov.bd).

The temperatures are measured in degrees Celsius. The

temperature data is a continuous univariate time series as

it contains a single variable (temperature) which is

measured at every instant of time. However, this data was

merged into monthly intervals transforming it to a discrete

univariate time series.

The Box-Jenkins Method

This study follows the Box-Jenkins methodology for

modeling. The following conceptual framework proposed

by Box et al. (1976) is considered in this study.

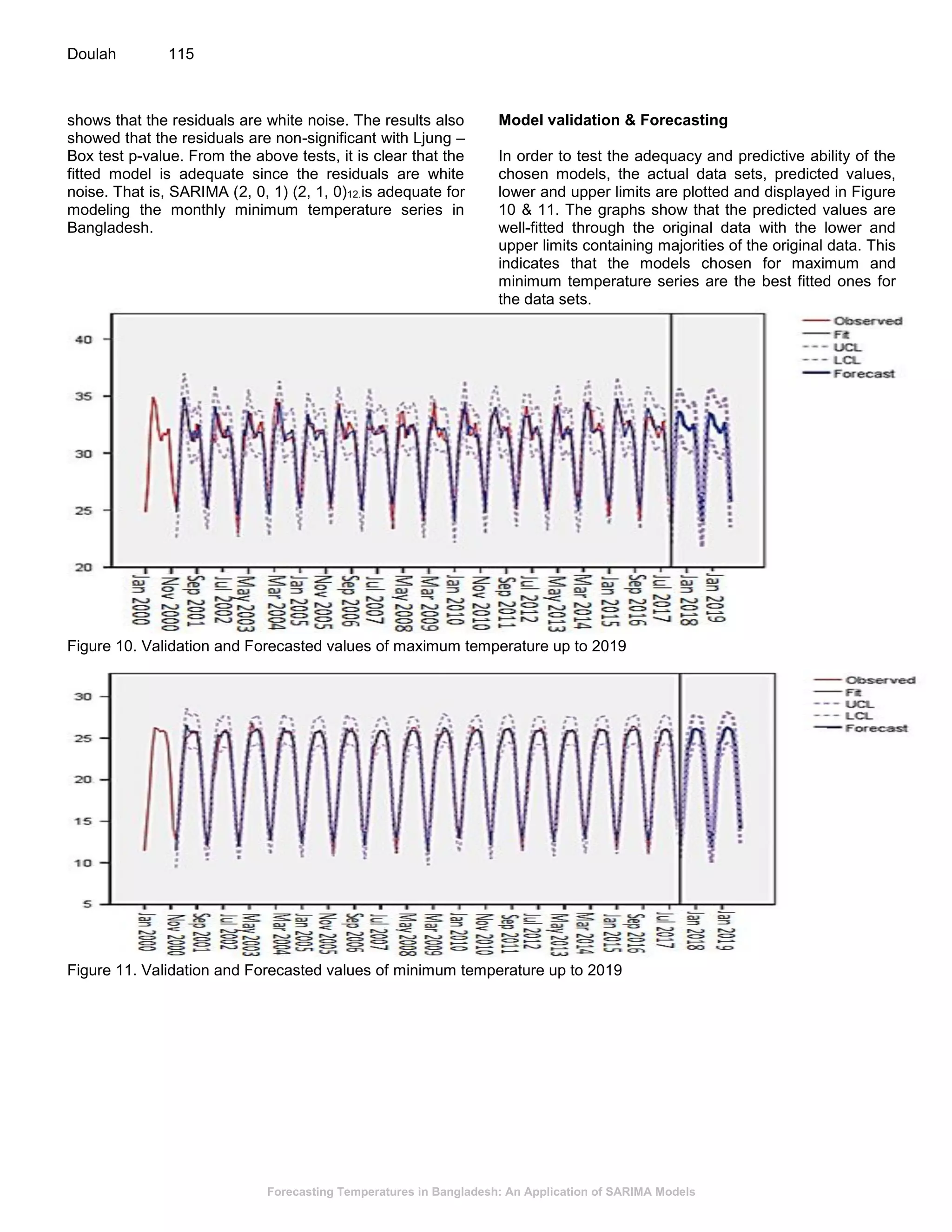

Figure 1. Box- Jenkins ARIMA Model

Seasonal ARIMA (SARIMA) Model

Gurudeo and Mahbub (2010) alludes that most natural

factors like temperature have strong seasonal

Components. It is therefore necessary to use

autoregressive and moving average polynomials that

identify with the seasonal lags. One such model is the

SARIMA model. SARIMA model is an extension of ARIMA

model and it is applied when the series contains both

seasonal and non-seasonal behavior. SARIMA model is

sometimes called the multiplicative seasonal

autoregressive integrated moving average and is denoted

by SARIMA (p,d,q)(P,D,Q)S. The Seasonal AR can be

written as:

tt

s

p yB )(

The Seasonal MA can be written as

t

s

Qt By )(

The seasonal differencing is expressed as

sttt

s

yyyB )1(

Combining the above equations, we get SARIMA

t

s

Qqt

Dsds

pp BByBBBB )()()1()1)(()( 0

Where the constant equals

)]1)(1[( 110 pp

Where p represents non-seasonal AR order, d represents

non seasonal differencing, q represents non seasonal MA

order, P represents seasonal AR order, D represents

seasonal differencing, Q represents seasonal MA order, S

represents seasonal order (for monthly data S = 12 ) ty

represents time series data at period t, B is the backward

shift operator (

k

t t kB y y ) and t is the random shock

(white noise error).

Stationarity Analysis

One of the important types of data used in empirical

analysis is time series data. The empirical work based on

time series data assumes that the underlying time series

is stationary. The time series analysis based on the

stationary time series data. In this section we briefly

discuss on stationary and non-stationary time series. A

stochastic process is said to be stationary if its mean and

variance are constant over time. Otherwise it will be non-

stationary. Why are stationary time series so important?

Because if a time series is non-stationary, we can study its

behavior only for the time period under consideration.

Each set of time series data will therefore be for a

particular episode. As a consequence, it is not possible to

generalize it to other time periods. Therefore, for the

purpose of forecasting, such (non-stationary) time series

may be of little practical value. How do we know that a

particular time series is stationary? There are several tests

of stationary. Here we used graphical and analytical

recognized test. Graphical test: if we depend on common

sense, it would seem that the time series depicted in figure](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/pdf-180918151412/75/Forecasting-Temperatures-in-Bangladesh-An-Application-of-SARIMA-Models-2-2048.jpg)