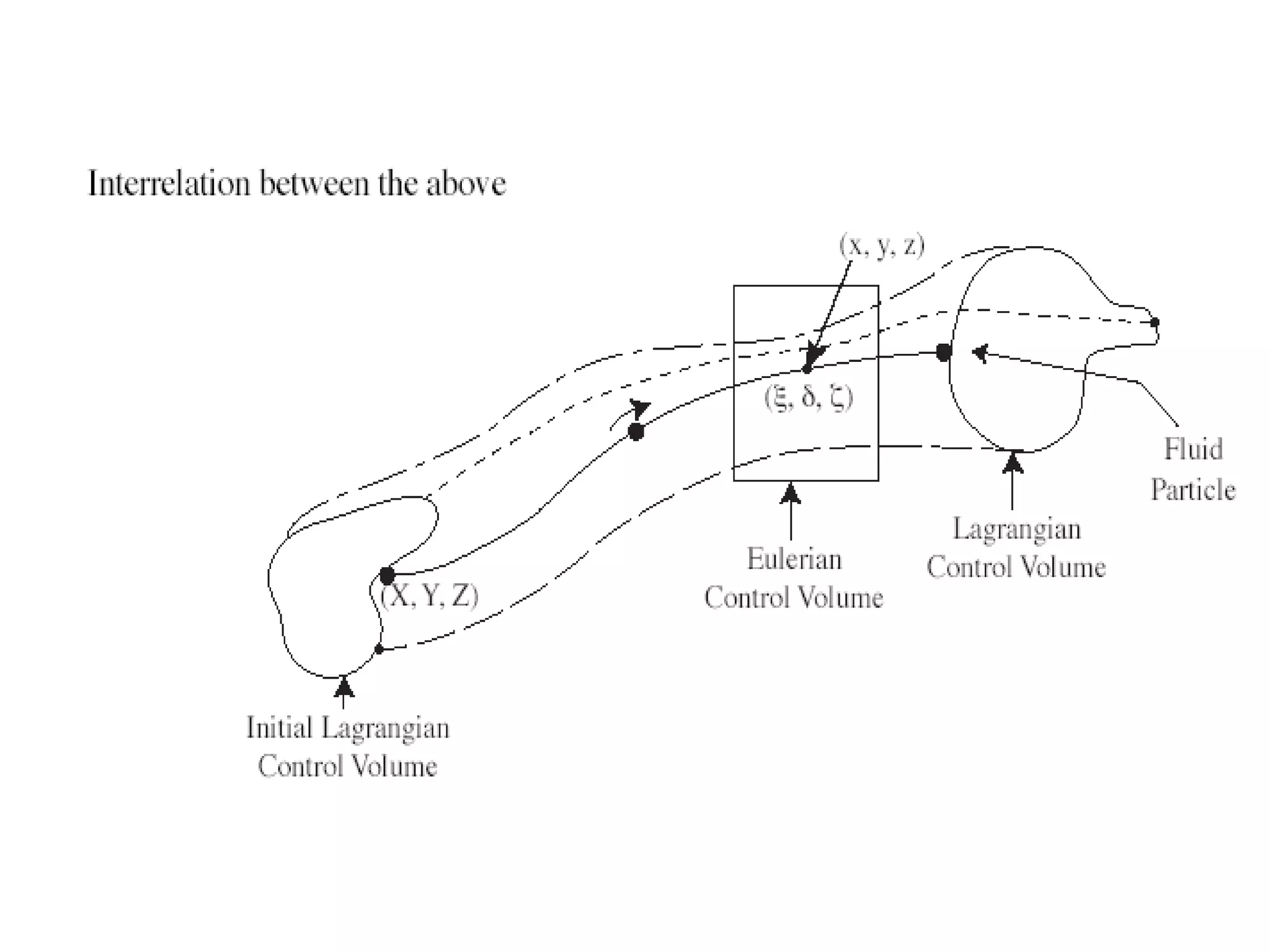

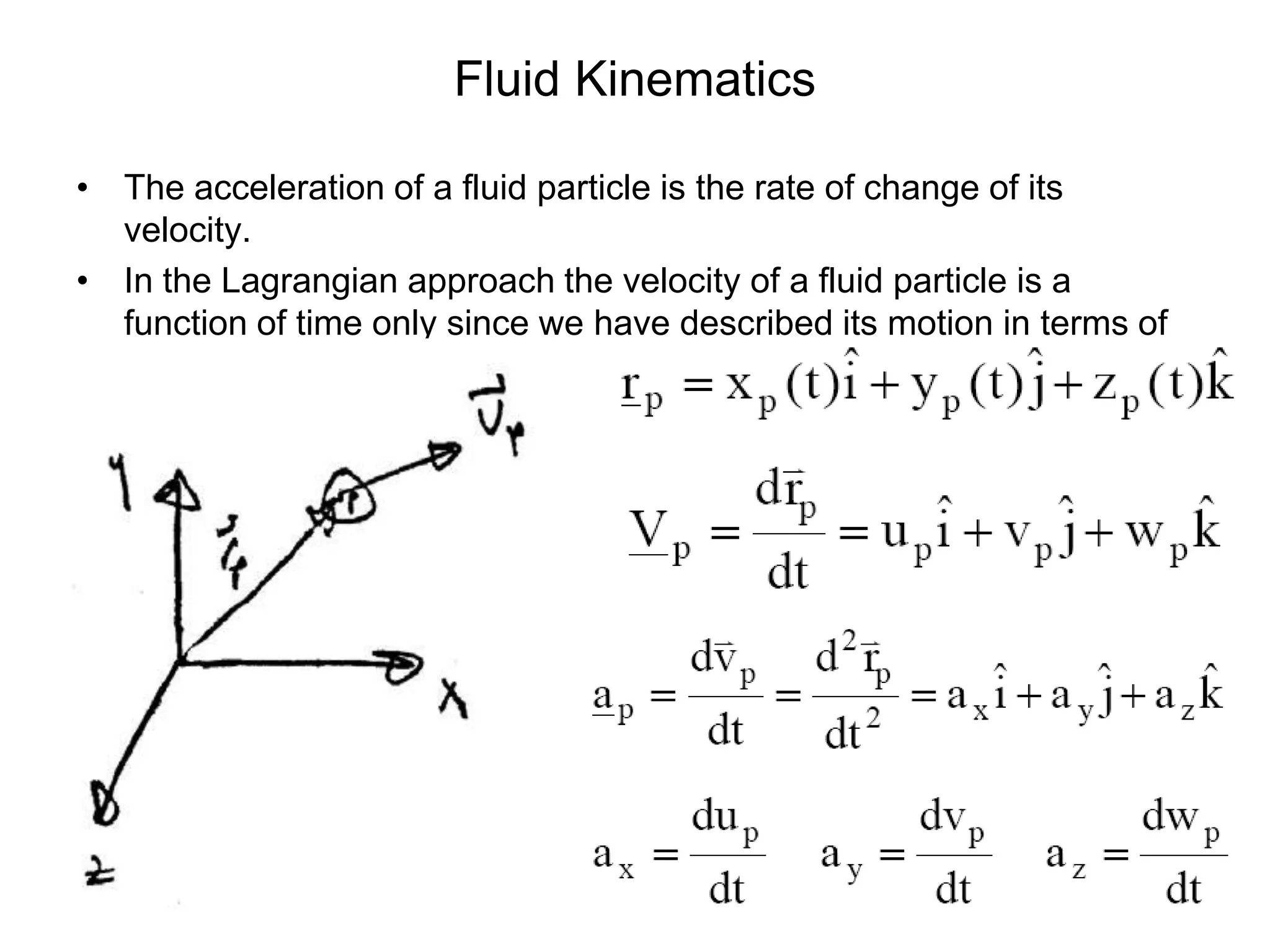

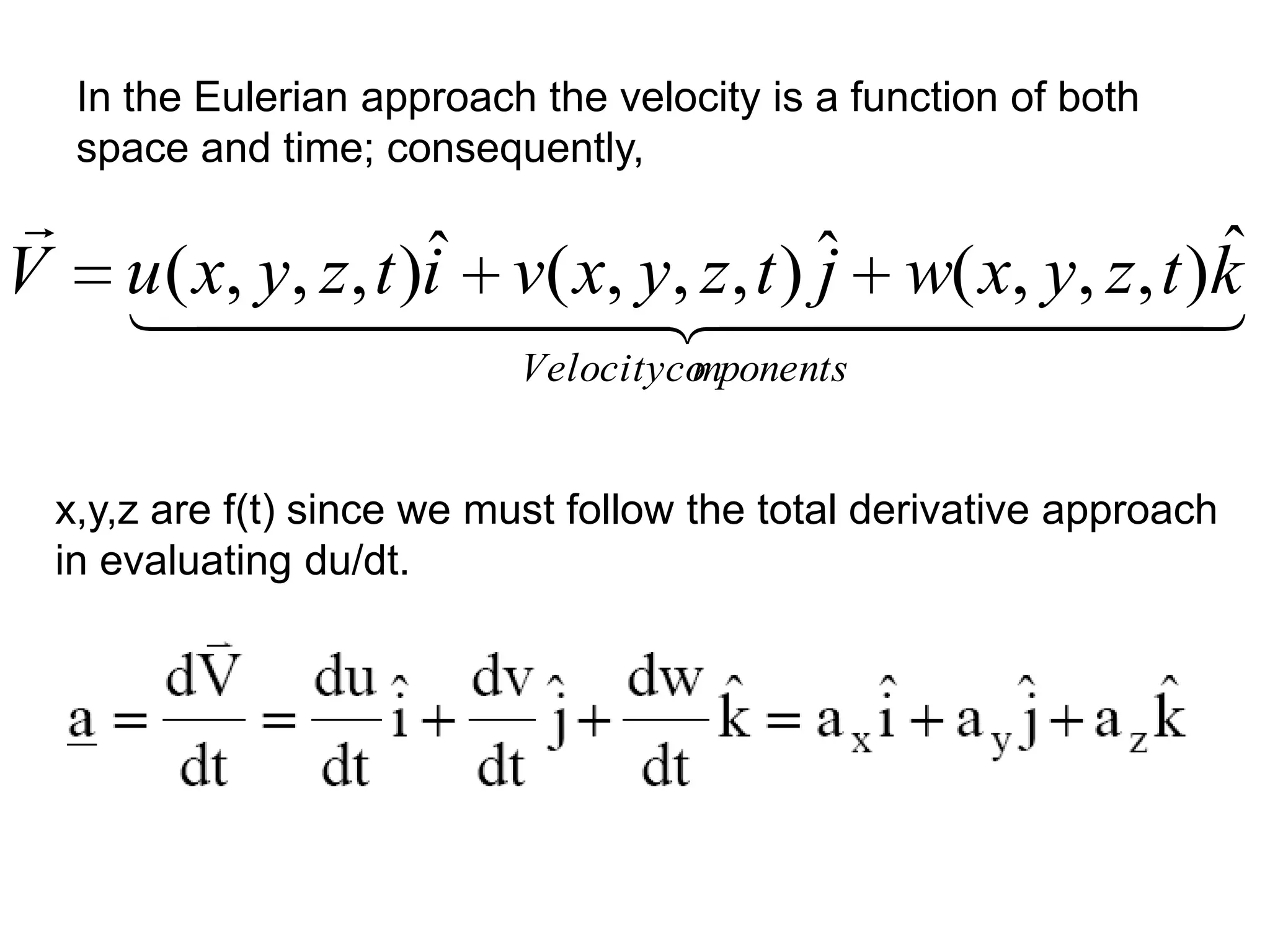

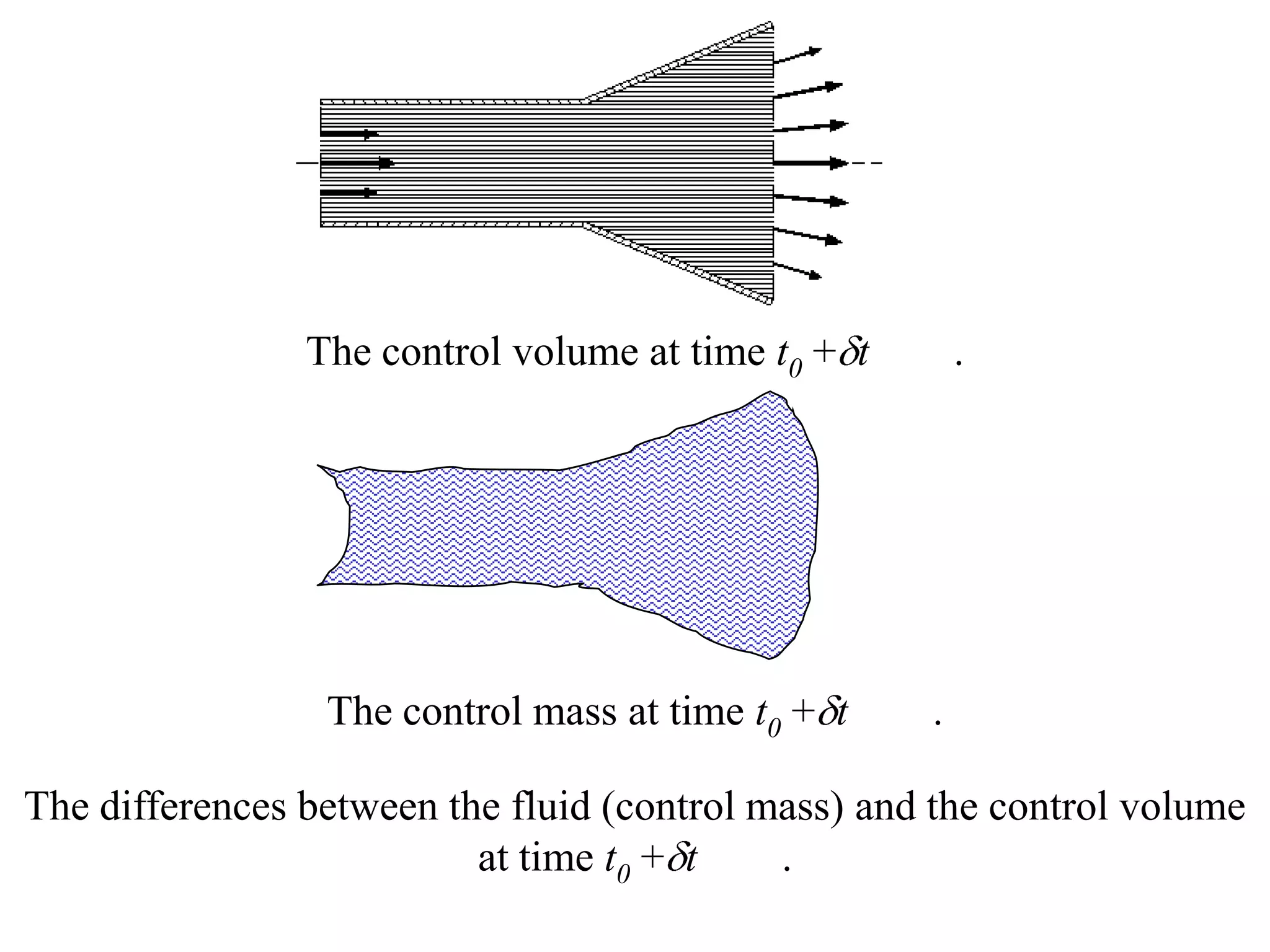

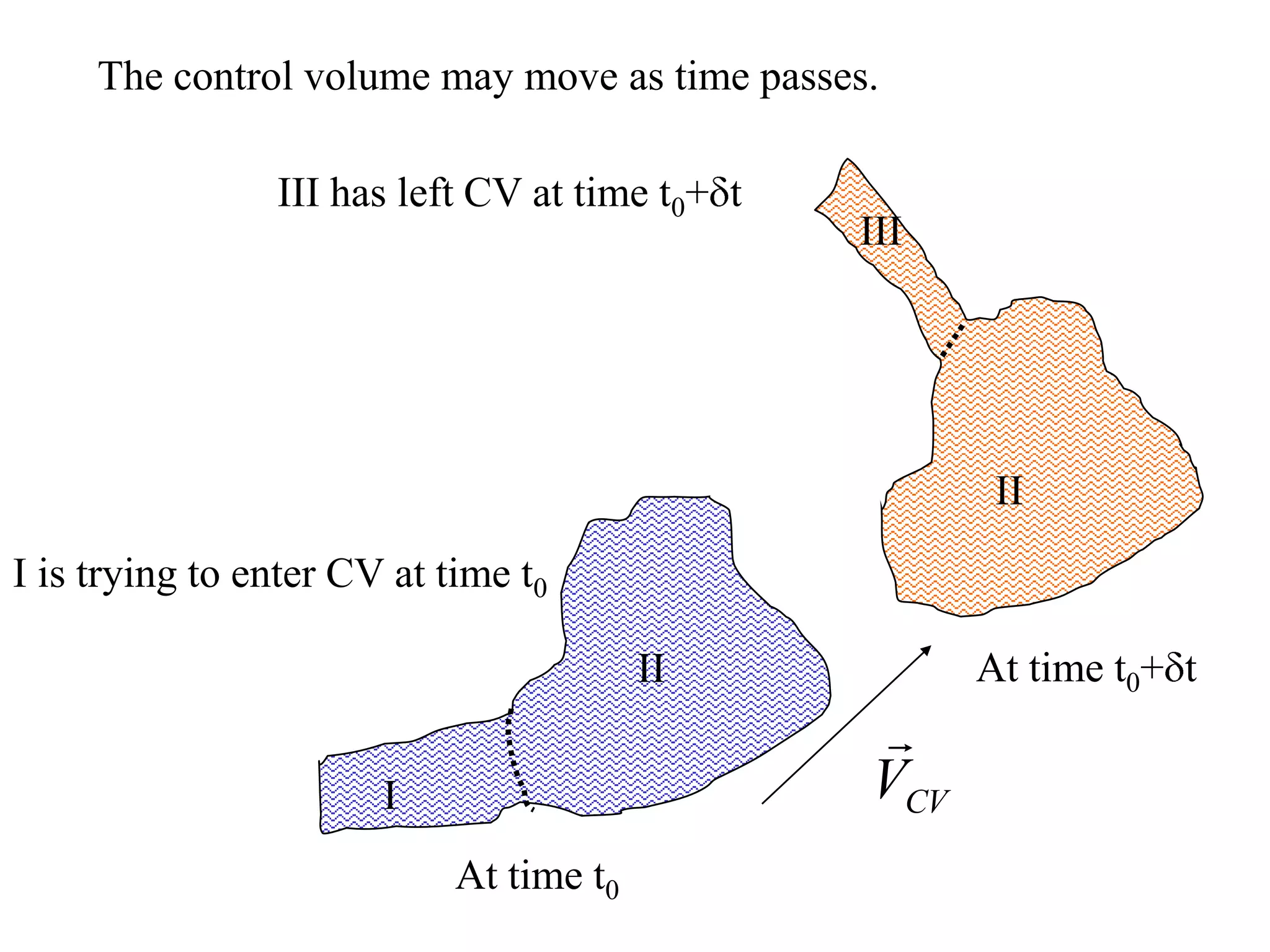

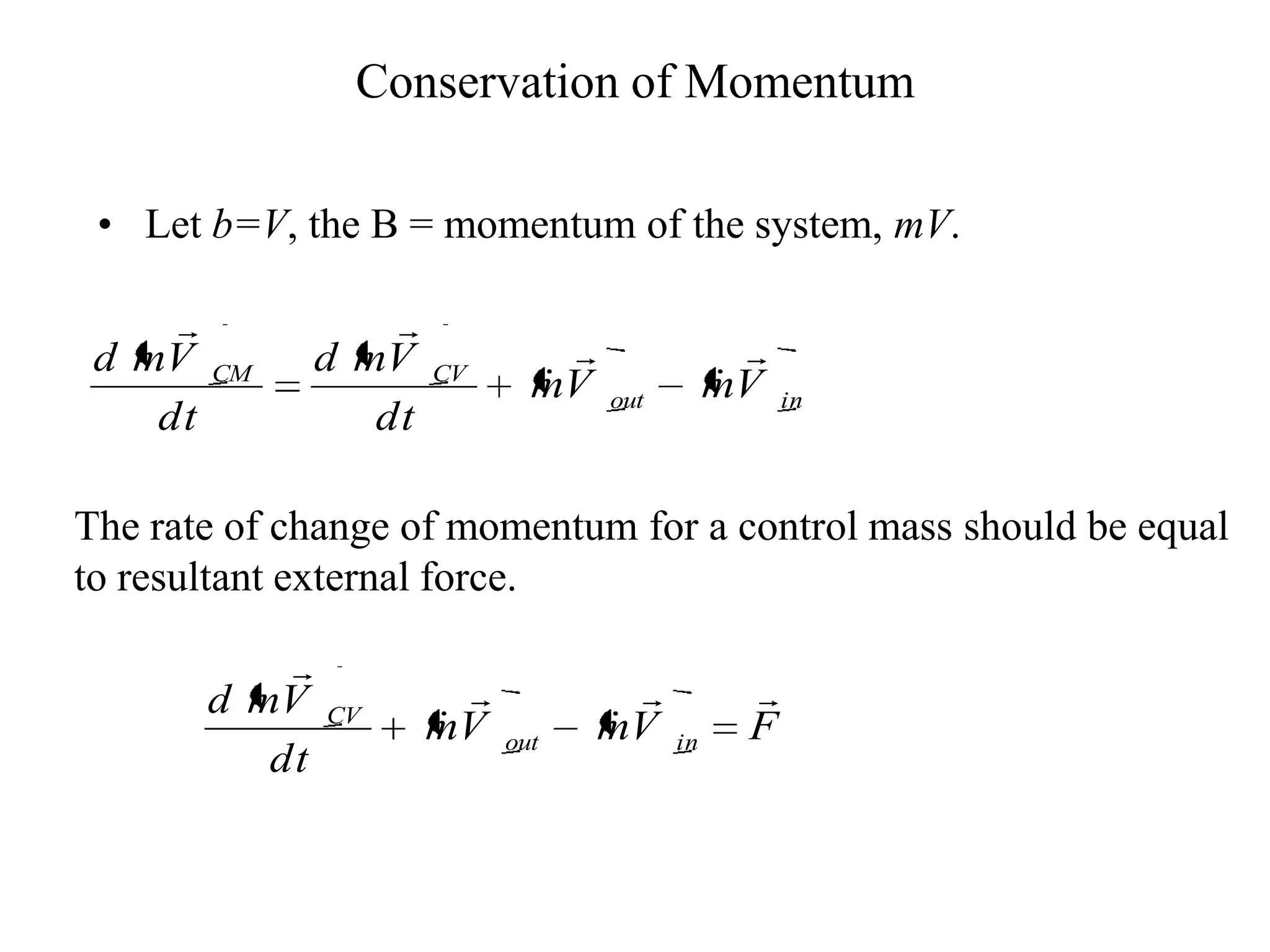

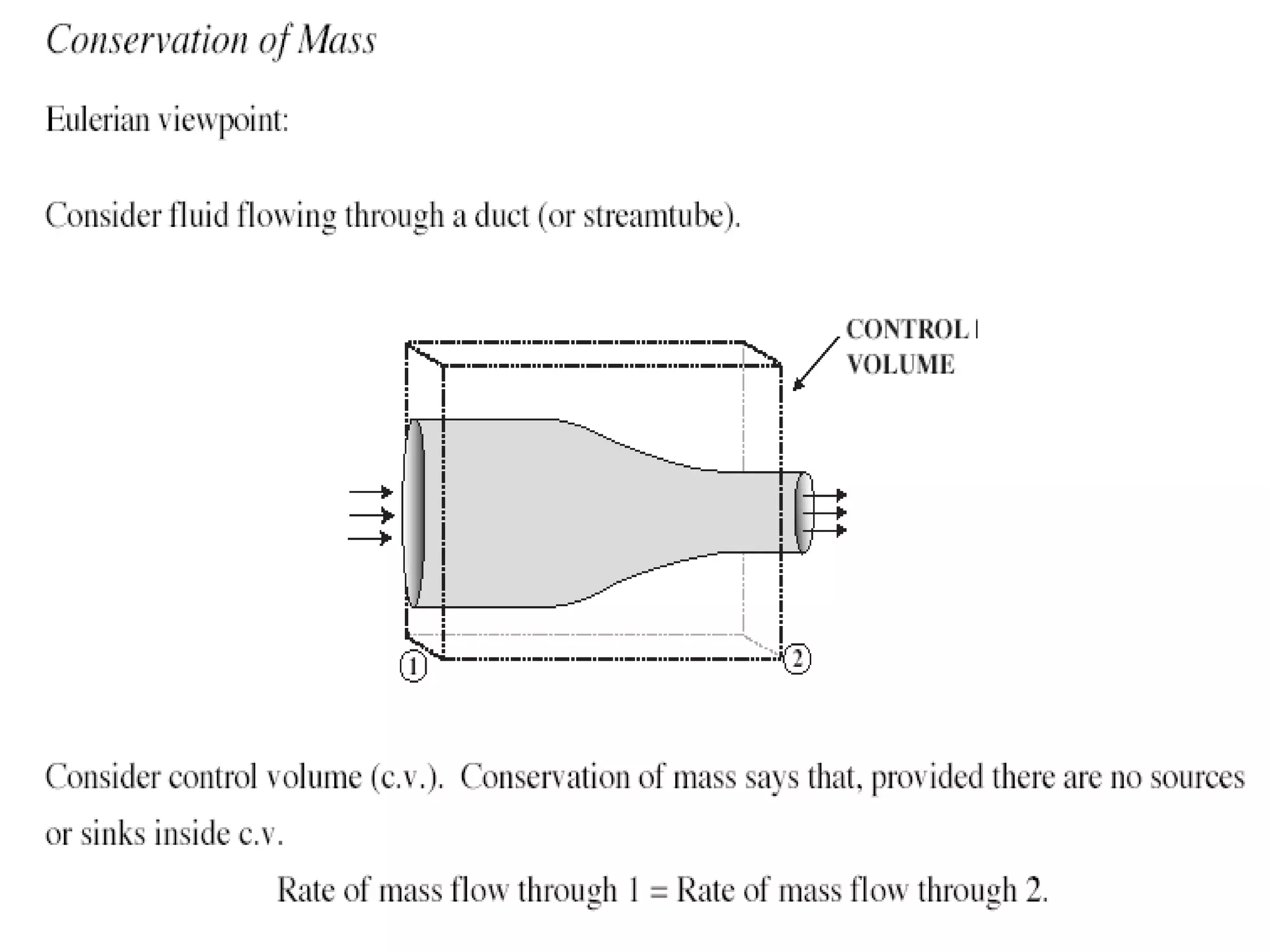

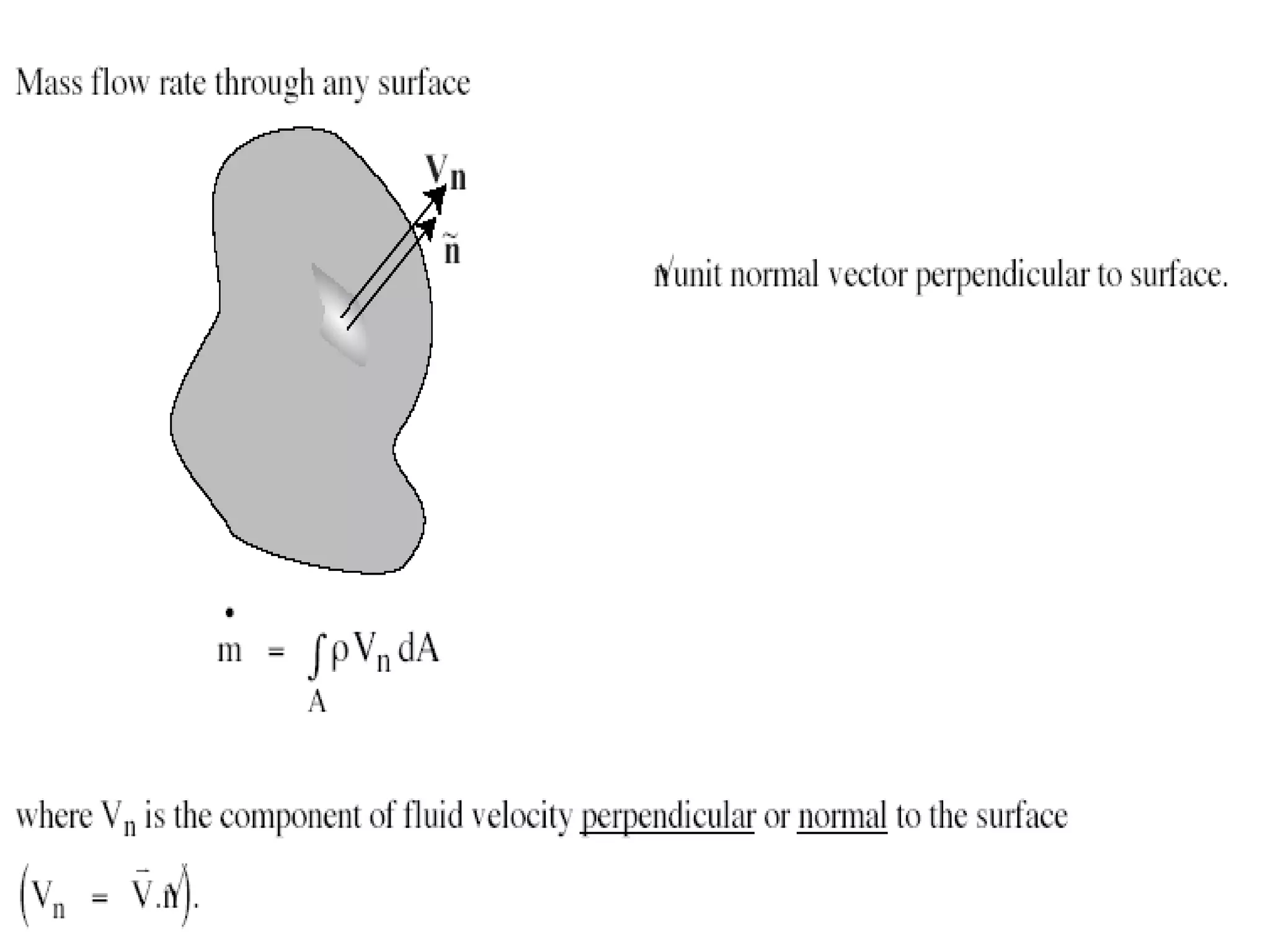

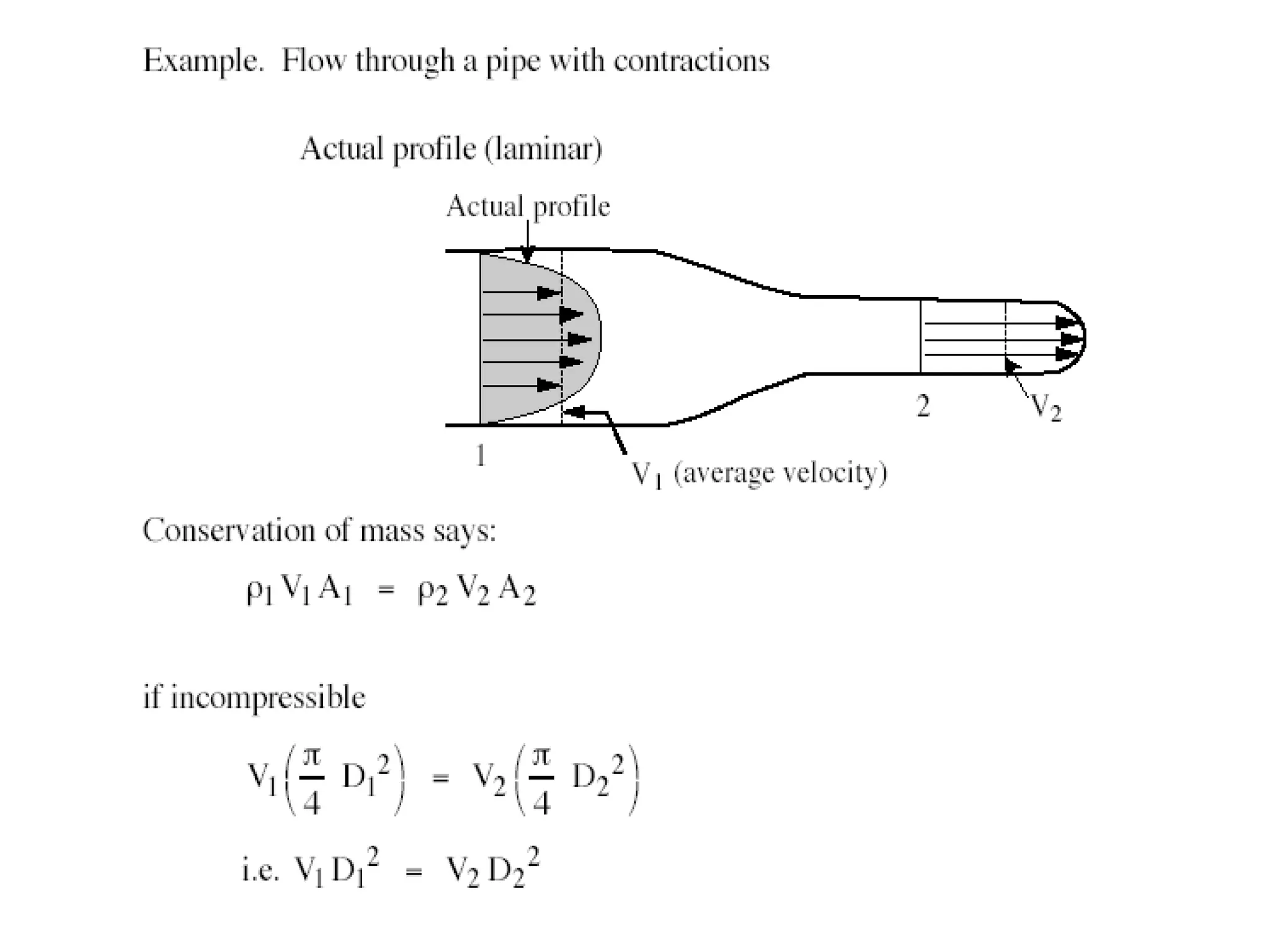

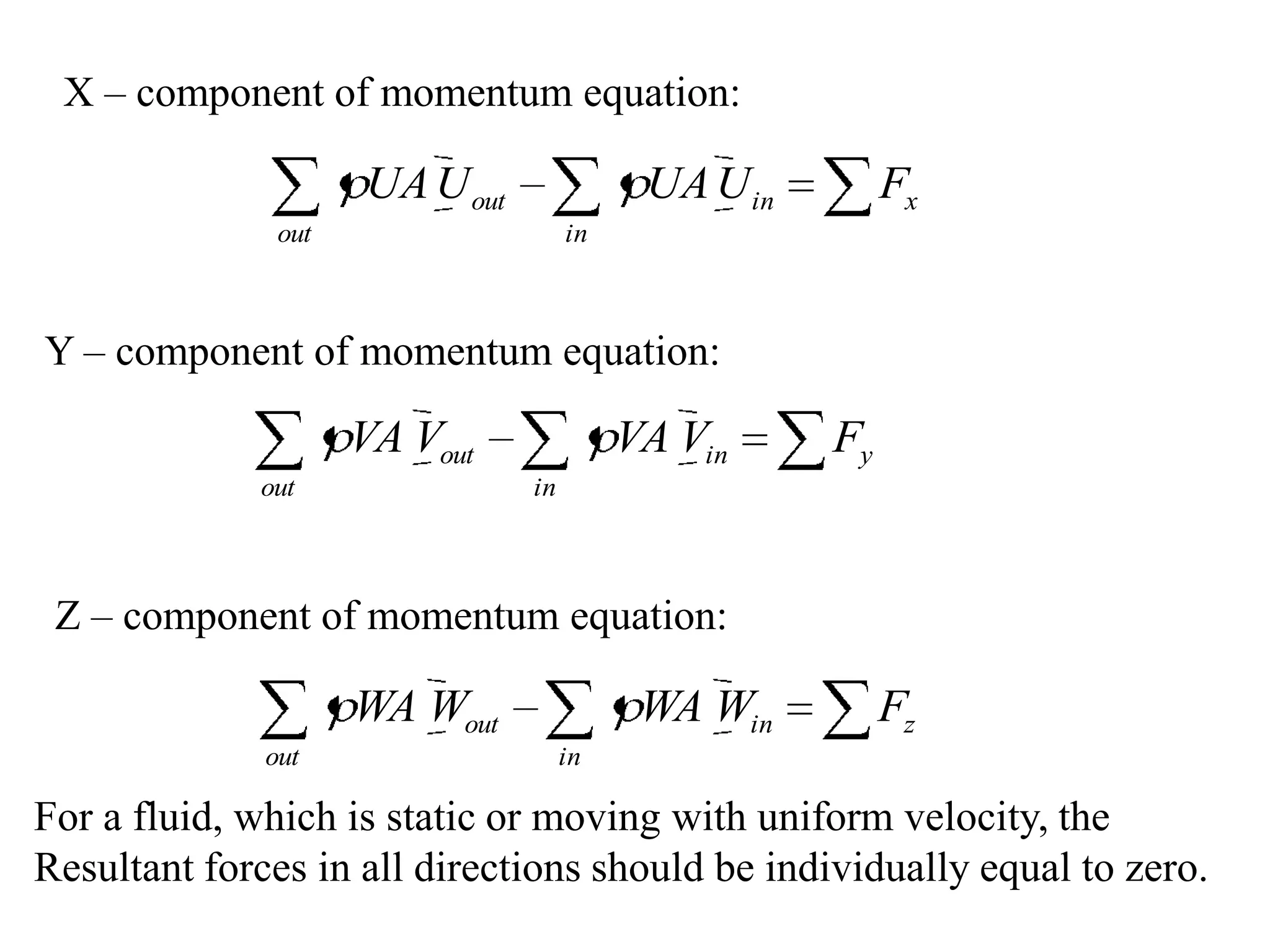

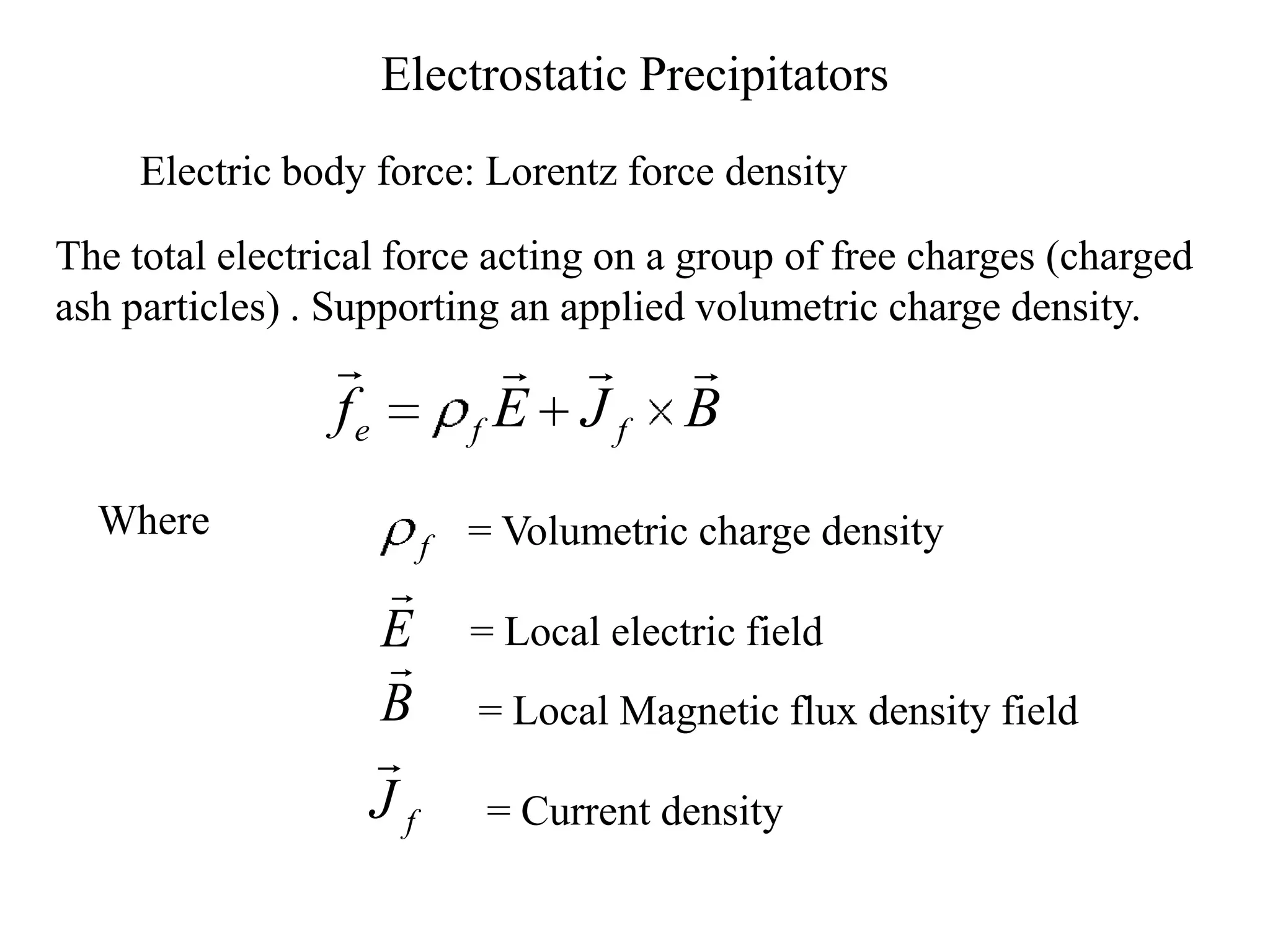

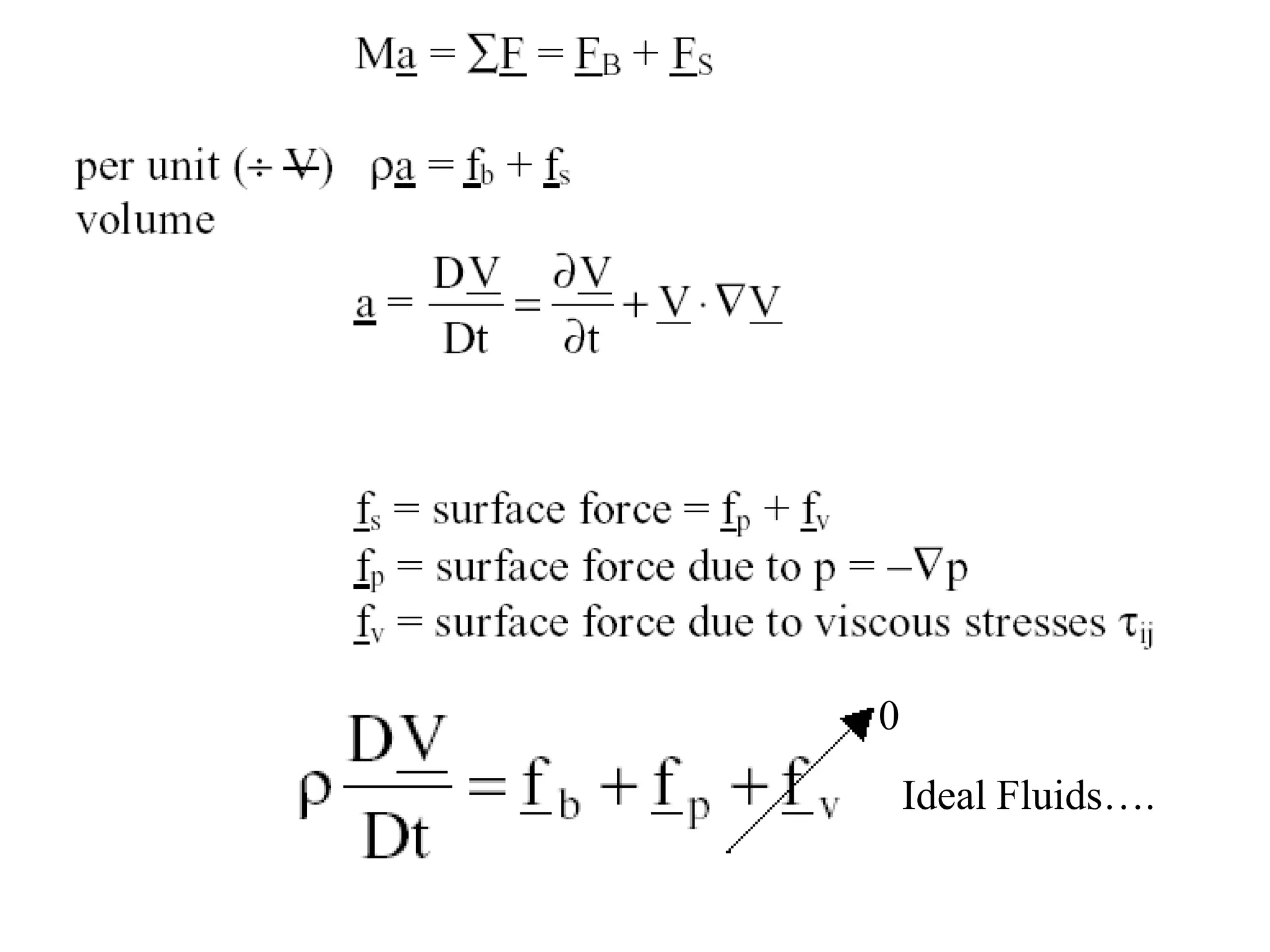

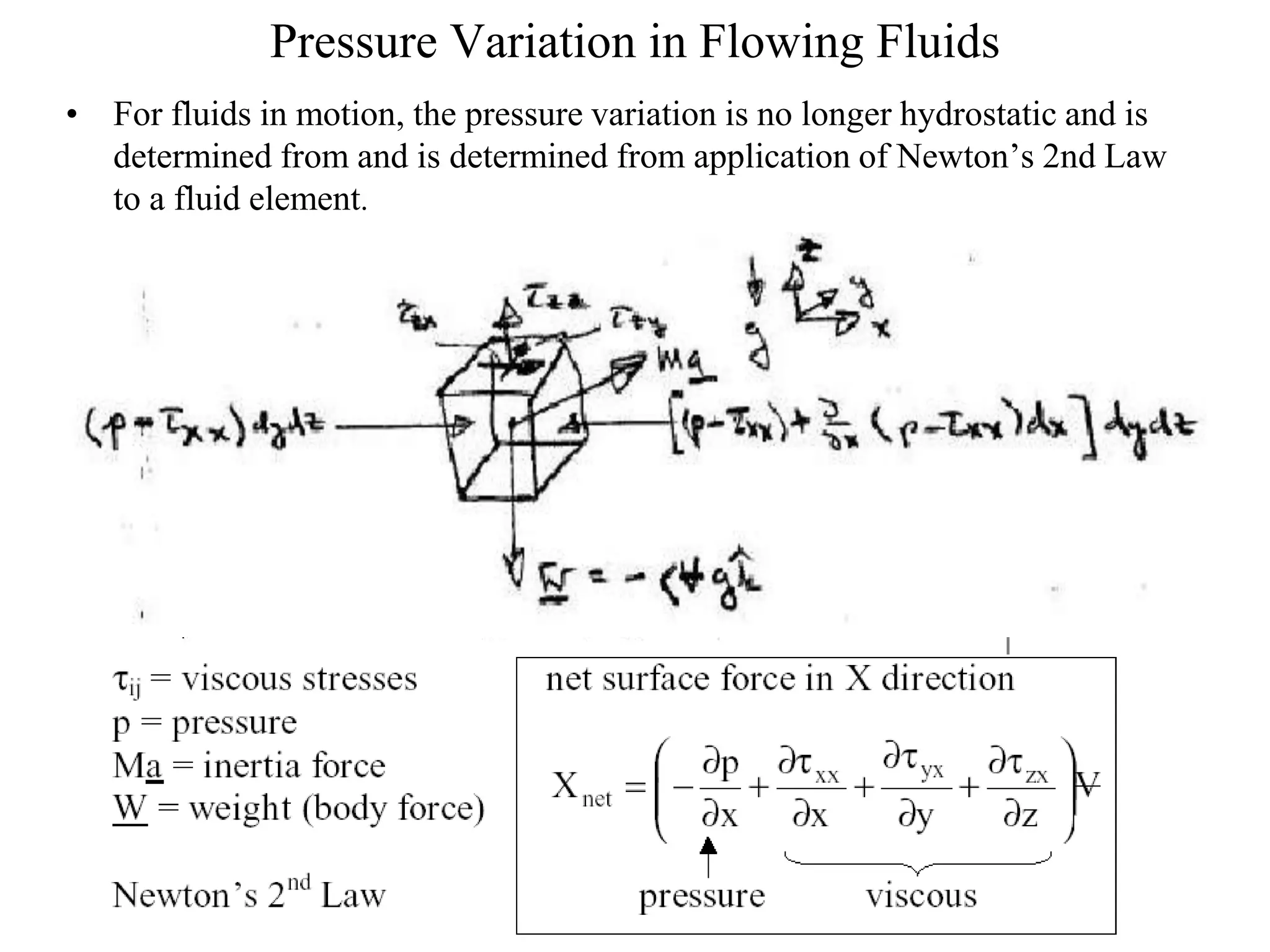

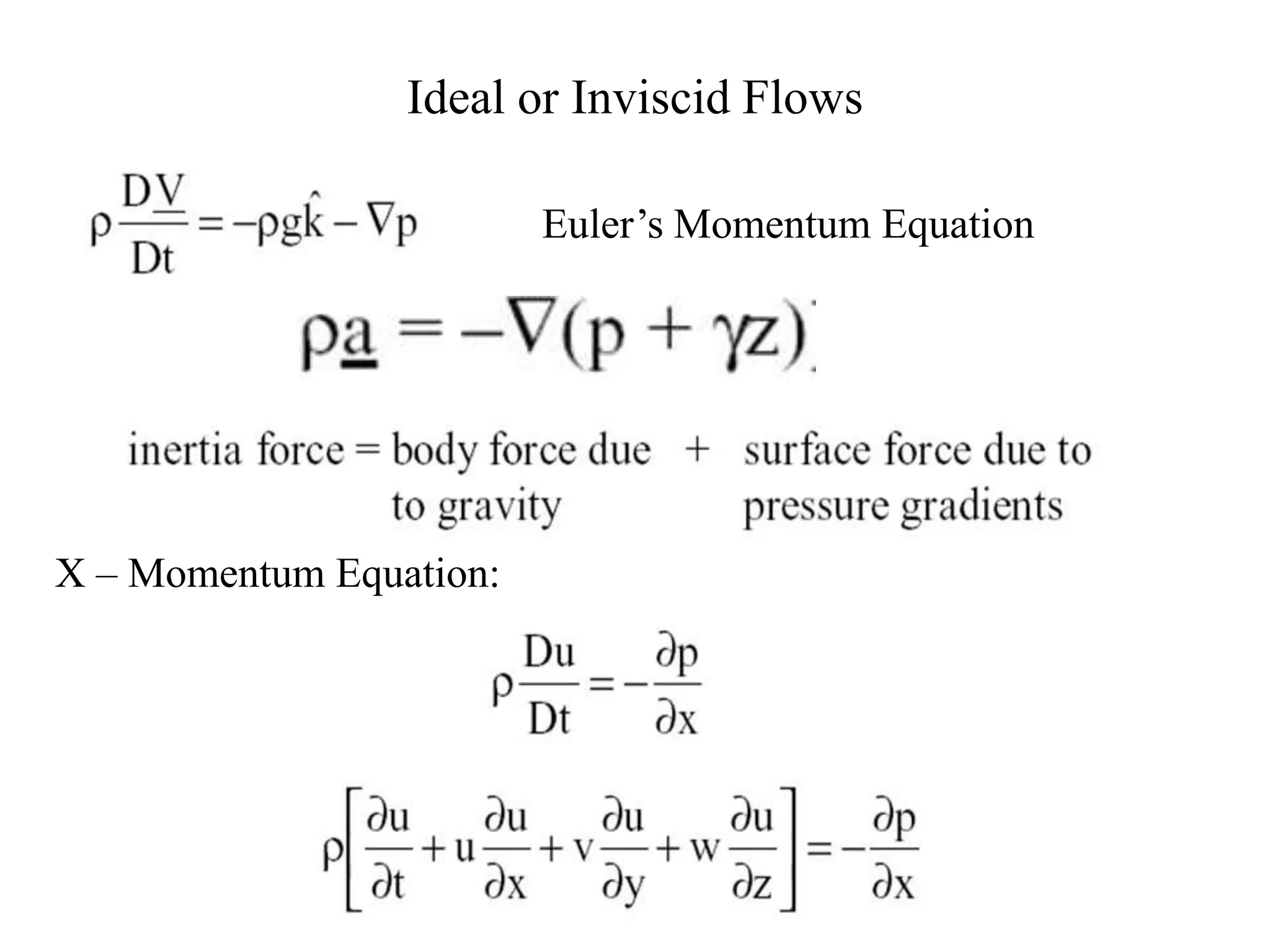

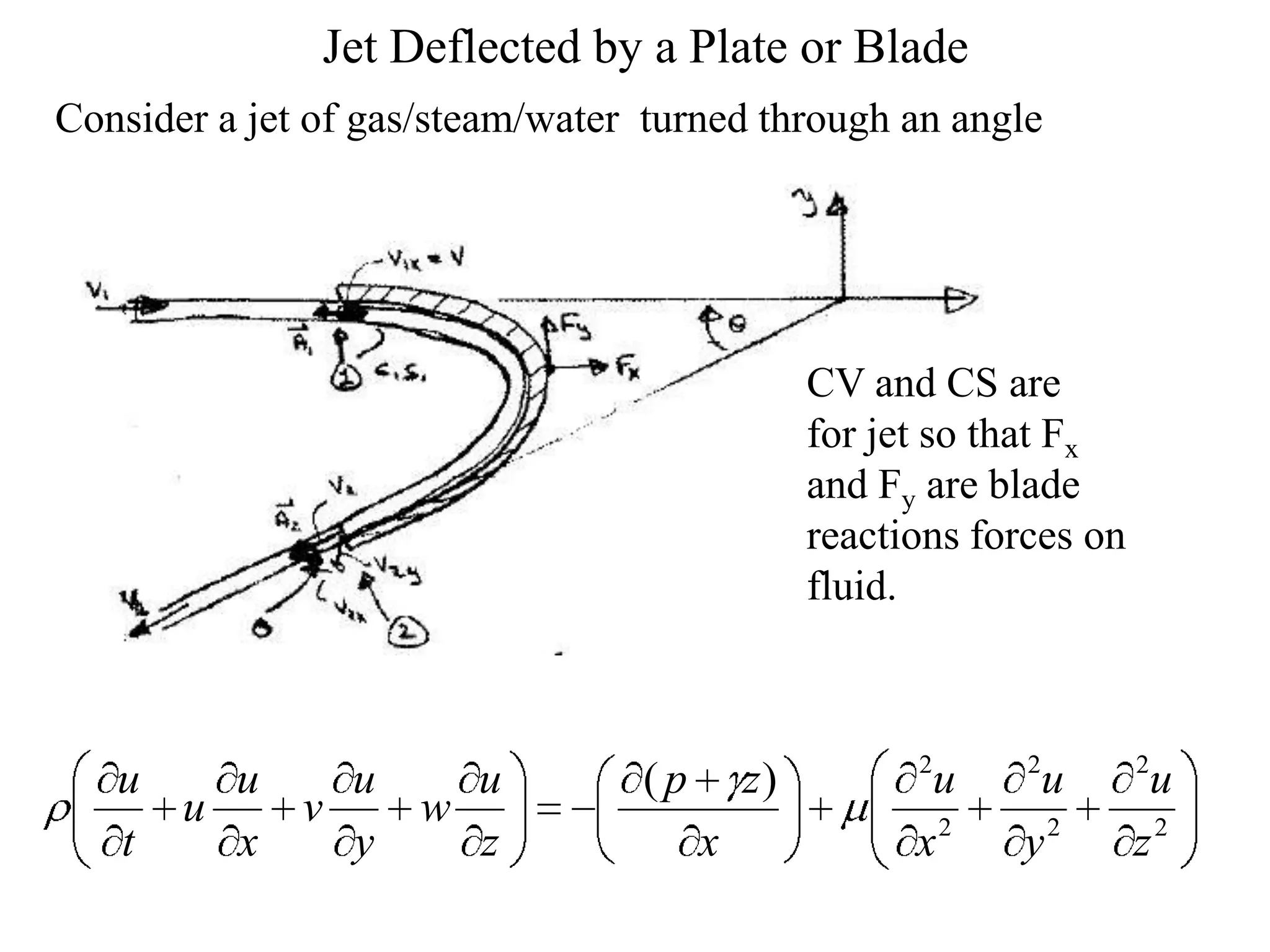

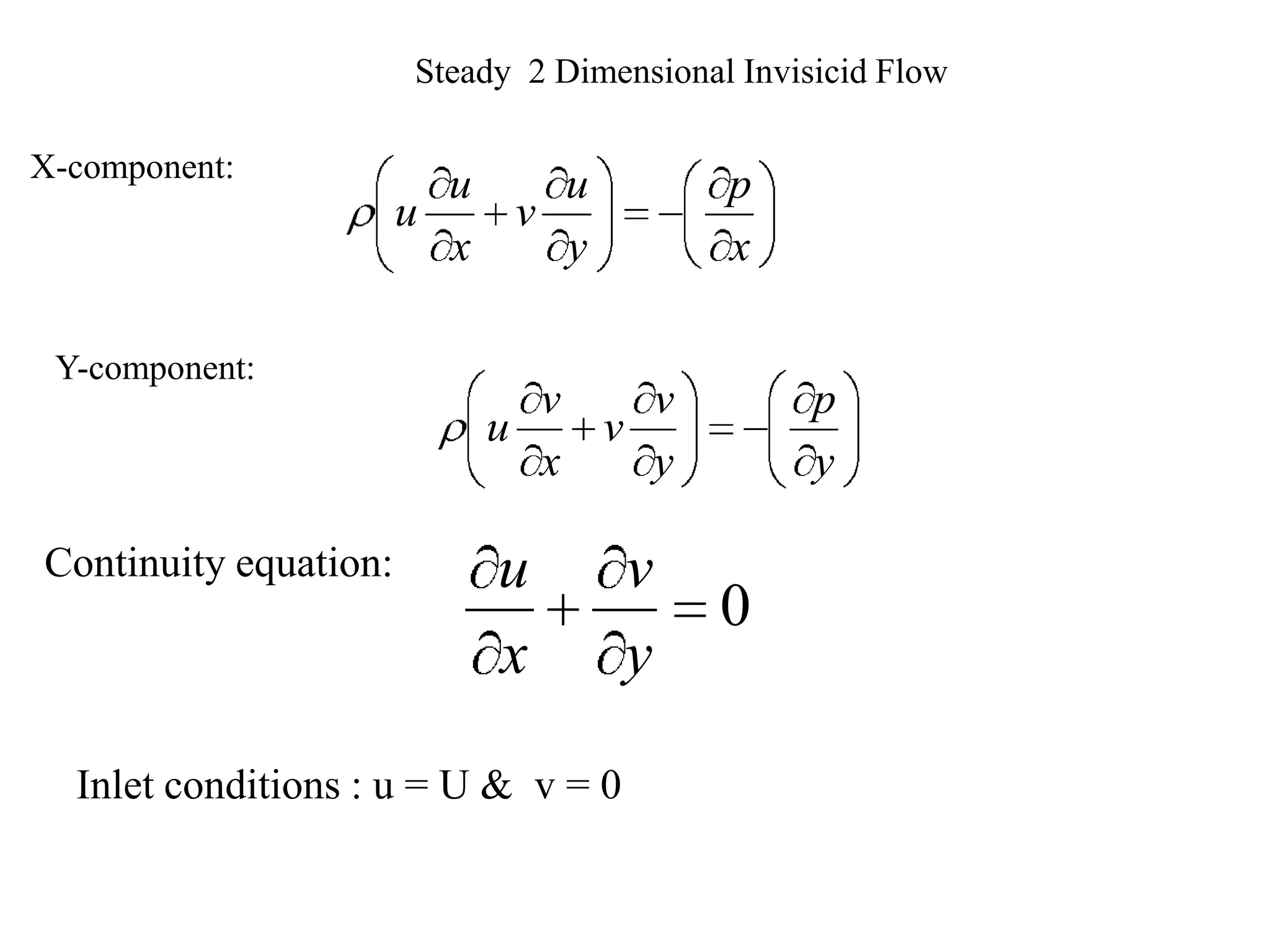

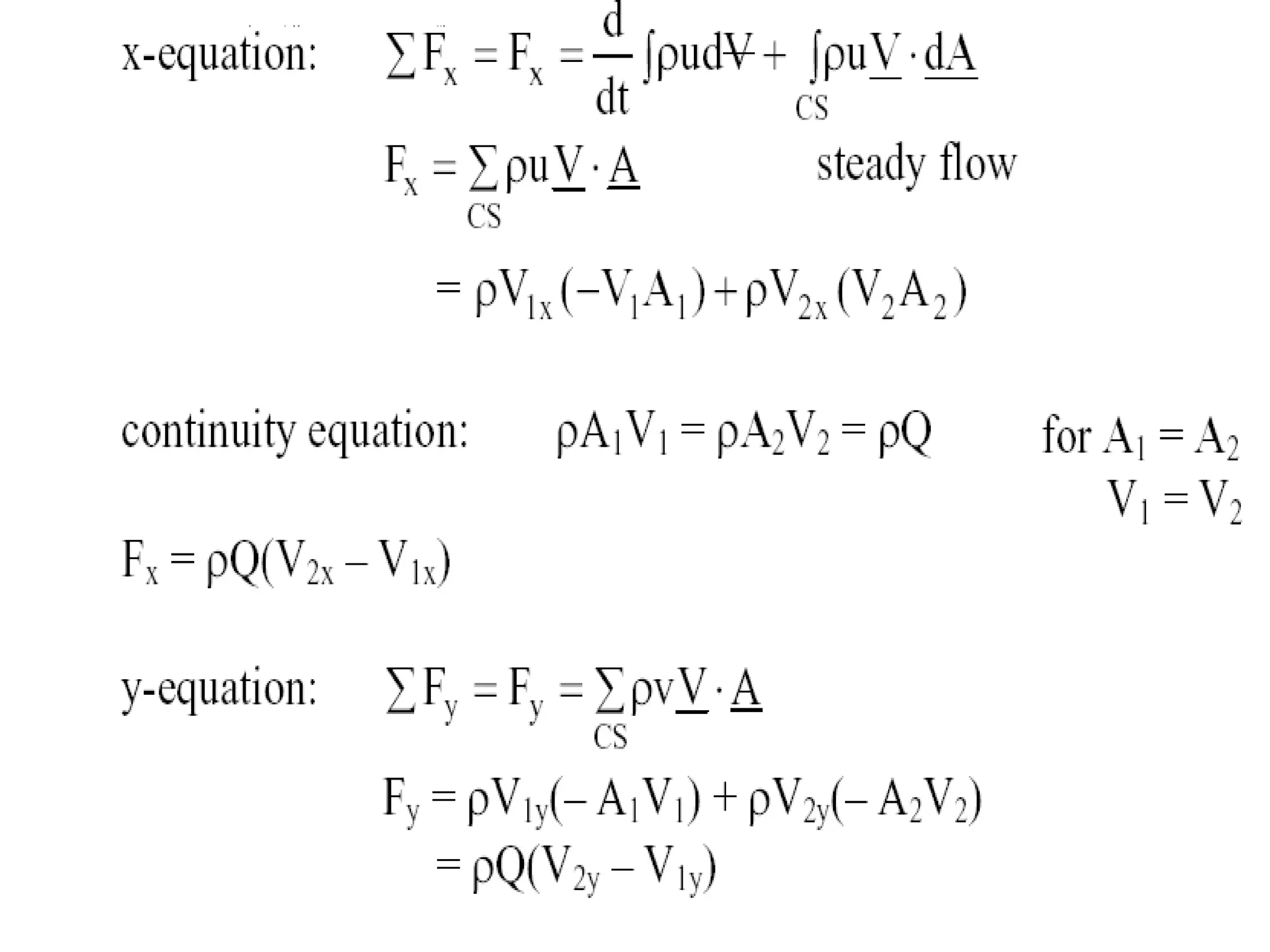

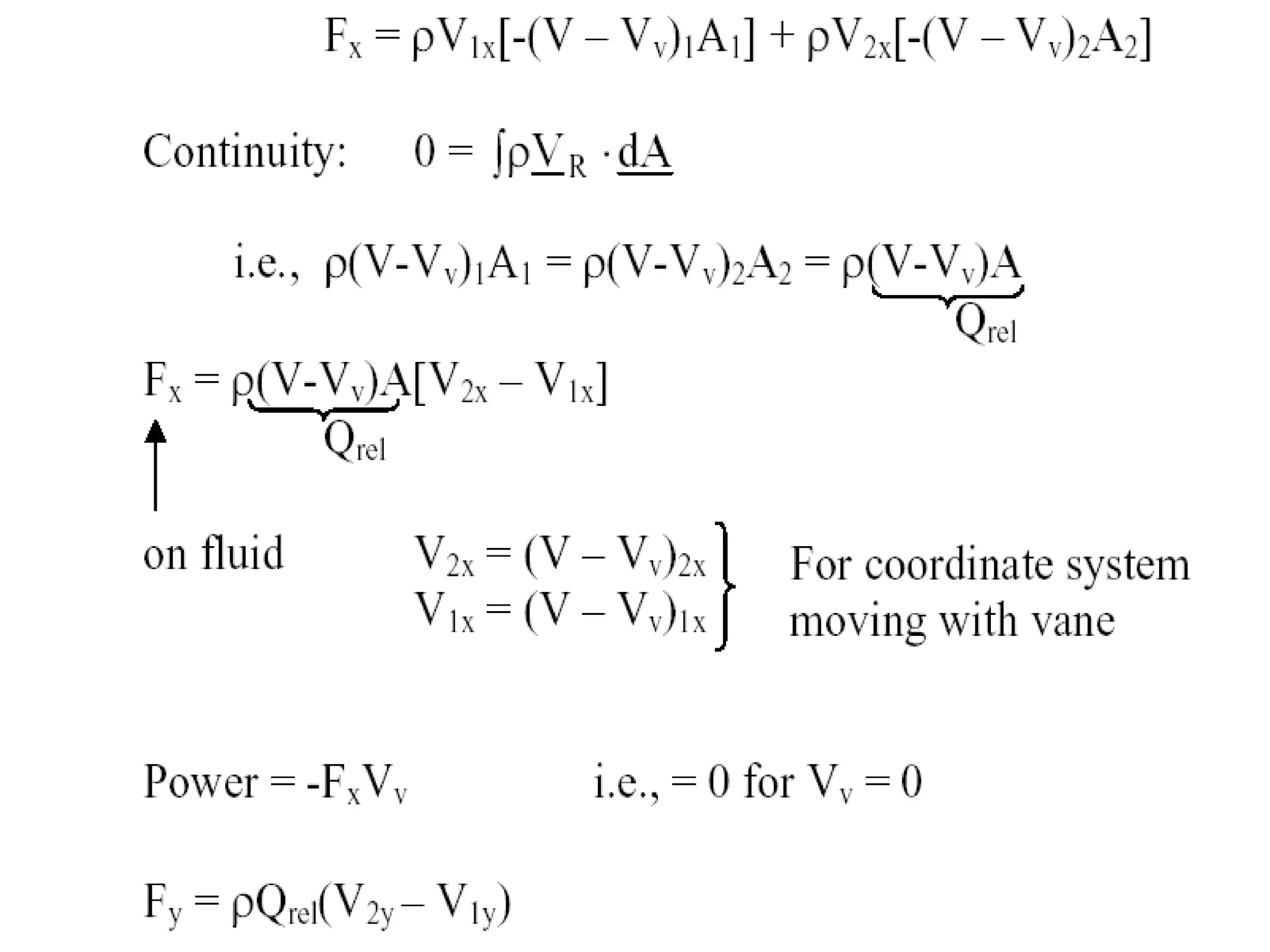

This document provides information about mathematical models for fluid mechanics. It discusses key concepts like streamlines, streamtubes, fluid kinematics, and the conservation laws applied to control volumes using Reynolds Transport Theorem. It also covers fluid properties like pressure variation, ideal fluids, comparison of inertial and viscous forces, and Euler's equation for one-dimensional flow. Important applications of the momentum equation are also highlighted, including jet deflection by a plate and the Navier-Stokes equations in differential form.