This document describes the development of a magnetic component design environment. It includes the development of an automated core loss measurement system to characterize magnetic materials, a database to store measurement data, and a design software tool. The core loss measurement system allows for easy and automated measurement of core loss over a range of frequencies and flux densities. Measured data is stored in a database, which can be accessed by the design software to enable accurate prediction of core losses during the design process. Validation measurements on inductors showed errors between predicted and measured losses and temperatures were less than 10%, demonstrating the effectiveness of the design environment for improving magnetic component design.

![Chapter 2

Magnetic Materials Overview and

Comparison

The history of magnetism begins in the 6th century B.C. when the Greek philosopher Thales discovered

magnetic properties of a mineral called magnetite. He noticed that his walking stick that had a metal ending

was attracted by a rock made of magnetite. However, the first scientific study on magnetism was published

in 1600 by William Gilbert, where the physical background of magnetic forces was explained. Later, the

science of electromagnetism was shaped by scientists like Faraday, Maxwell, Oersted and Hertz.

Parallel to the developments in the magnetic theory, considerable attention was focused on understanding

different magnetic materials and producing materials with desirable characteristics. Since the performance

of magnetic components used in power electronics and in other fields of electrical engineering greatly de-

pends on material characteristics, there is always a need to produce materials with better characteristics.

However, there is no perfect magnetic material that would meet all the designers requirements. Therefore

designing magnetic components is always a tradeoff between cost, size and performance indexes. Because

of this, knowing the characteristics of different magnetic materials and their advantages and disadvantages

is essential for the process of designing magnetic components.

This chapter gives a systematic overview of the magnetic materials used in modern day power elec-

tronics. It lists advantages and disadvantages of different material groups. This gives the basis for their

comparison, which is a first step in magnetic component design. Moreover, manufacturing processes for

each of the groups are described. This is important for better understanding all the differences and similari-

ties between different material groups.

2.1 Classification of Magnetic Materials

According to their magnetic properties, all materials can be classified in three groups [1], [3]:

• Diamagnetic materials

• Paramagnetic materials

3](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/b2c598c0-acc4-4f16-a555-962d4c8820c3-160325211659/85/Final_report-17-320.jpg)

![CHAPTER 2. MAGNETIC MATERIALS OVERVIEW AND COMPARISON

Diamagnetic Paramagnetic Ferromagnetic

Superconductor Cesium Cobalt

Graphite Aluminum Iron

Copper Lithium Nickel

Lead Magnesium

Silver Sodium

Water

Table 2.1: Some typical representatives of diamagnetic, paramagnetic and ferromagnetic materials.

• Ferromagnetic materials

Diamagnetic materials (Diamagnets) are materials that have magnetic permeability less than µ0 (relative

permeability is less than 1). These materials cause the lines of magnetic flux to curve away from the ma-

terial and hence it appears as they create a magnetic field opposed to an external magnetic field. Such a

behavior is common to most of materials present in nature (and often these materials are referred to as non-

magnetic). However, the effect of repulsion when exposed to external magnetic field is so weak that it is

usually not noticed at all. The only exceptions are superconductors which completely exclude the lines of

magnetic flux and can be regarded as perfect diamagnets.

Paramagnetic materials (Paramagnets) have relative permeability slightly higher than one. These ma-

terials are slightly magnetized in the presence of external magnetic field. However, in the absence of the

external magnetic field these materials retain no magnetization.

Ferromagnetic materials (Ferromagnets) have relative permeability much greater than one (typically

from 10 to 100000) [1]. These materials get magnetized in the presence of an external magnetic field and

unlike paramagnets do not immediately get demagnetized when the external field is removed. Ferromag-

netic materials are the only ones that can be used to produce considerable magnetic forces. These forces can

be noticed and felt and they are the ones that are generally associated with the phenomenon of magnetism

encountered in everyday life. These materials are relevant for the design of magnetic components for power

electronics. Some typical diamagnetic, paramagnetic and ferromagnetic materials found in nature are listed

in Table 2.1.

Ferromagnetic materials can be further divided into two groups depending on their coercive force (Hc)

[1],[3]. These two groups are:

• Hard magnetic materials

• Soft magnetic materials

According to [1], hard magnetic materials are those that have Hc > 10000 A/m. These materials are often

called permanent magnets. Usually they also have very high value for remanent induction Br. Therefore,

these materials are very hard to demagnetize (hence the name permanent magnets). Typical applications of

such materials are for electrical motors and generators, sensing devices and mechanical holding.

Soft magnetic materials typically have Hc < 1000 A/m. Therefore, they are characterized by much

narrower BH loops compared to hard magnetic materials. Moreover, it is much easier to change magnetic

alignment in the structure of these materials. They are widely used in modern electrical engineering and

4](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/b2c598c0-acc4-4f16-a555-962d4c8820c3-160325211659/85/Final_report-18-320.jpg)

![CHAPTER 2. MAGNETIC MATERIALS OVERVIEW AND COMPARISON

electronic applications. In fact, most of magnetic components in power electronics use cores made of these

materials.

Materials that have Hc in the range of 1000 – 10000 A/m are considered to be somewhat between soft

and hard, however there is no general term that would describe such materials [3]. These materials are

mainly used as recording media.

Since soft magnetic materials are the most relevant for power electronics, we will mainly focus on them.

They can be further divided into two groups based on their chemical composition:

• Ferrites (ferrimagnetic materials)

• Iron (Fe) based soft magnetic materials (ferromagnetic materials in narrow sense)

Here it is important to stress the difference between the terms, since often in literature soft magnetic ma-

terials based on iron are referred to as ferromagnetic although they, together with ferrimagnetic materials,

belong to the larger group of ferromagnetic materials. However it is often said that soft magnetic materials

based on iron are ferromagnetic materials in narrow sense [1].

Ferrimagnetic materials (ferrites) are ceramic materials made from oxides of iron and metals like man-

ganese (Mn), zinc (Zn) and nickel (Ni). Their main advantage is high electrical resistivity and relatively low

losses at high frequencies. However, these materials have quite low saturation flux density.

Ferromagnetic materials are made of metal alloys of iron and metals like silicon (Si), nickel, chrome

(Cr) and cobalt (Co). They have higher saturation flux density than ferrites, but also much higher electrical

conductivity (therefore higher losses due to eddy currents). This group of materials can be further divided

into several subgroups based on the manufacturing technology and material properties:

• Iron based alloys

• Powder iron

• Amorphous alloys

• Nanocrystalline alloys

The order in which these different material groups are listed corresponds to chronological order in which

they appeared and in which they have been manufactured and used in power electronics. Iron based alloys

are metal alloys of iron and silicon, nickel or cobalt. Powder iron cores are made from small iron (or other

material containing iron) particles which are mutually electrically isolated. Amorphous alloys are iron or

cobalt based alloys with special crystalline structure. They do not have crystal structure characteristic for

metals, but amorphous structure typical for glass or liquids. Nanocrystalline alloys are two phase materials

which have an amorphous alloy as a minority phase and FeSi crystals embedded into this amorphous phase.

Manufacturing processes as well as characteristics of these materials are given in the following sections.

Figure 2.1 illustrates described classification of magnetic materials

5](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/b2c598c0-acc4-4f16-a555-962d4c8820c3-160325211659/85/Final_report-19-320.jpg)

![CHAPTER 2. MAGNETIC MATERIALS OVERVIEW AND COMPARISON

Material Chemical comp. Curie temp. [◦C] Initial perm. Saturation flux density [T]

Magnesil 3%Si 97%Fe 750 1.5 K 1.5 – 1.8

Supremalloy 79%Ni 17%Fe 4%Mo 460 10 –50 K 0.66 – 0.82

Permalloy 80 78%Ni 17%Fe 5%Mo 460 12 – 100 K 0.65 – 0.82

Orthanol 50%Ni 50%Fe 500 2 K 1.42 – 1.58

Supermdur 49%Co 49%Fe 2%V 940 0.8 K 1.9 – 2.2

Table 2.2: Iron based alloys produced by Magnetics (data taken from [2] and [10]).

kilograms) the most used magnetic materials [2].

The main reason why silicon is added to iron is to reduce the conductivity and therefore reduce eddy

current loses. In addition, adding silicon reduces magnetostriction, and hence reduces the acoustic noise

caused by mechanical stress in material as a result of changing magnetic field. However, adding silicon also

has some negative effects. It reduces the saturation flux density, and can make the material lifetime shorter.

Also, adding more silicon results in a material that is very brittle. According to [1] the maximal percentage

of silicon that can be added to steel and that the material still keeps useful properties is 6.5 %. However,

iron-silicon alloy mostly used today is the one with 3 % silicon content.

Special kind of iron-silicon alloy is grain oriented silicon steel. This material has much higher perme-

ability and much lower loses in one direction than in the other. This is used when forming cores out of

this material. Namely it is always good to have lower loss and higher permeability in the direction along

the laminations, where the magnetic flux passes, than in the orthogonal direction. This property is called

anisotropy. When a magnetic material has the same magnetic properties in all directions it is called isotropic

and when this is not the case it is called anisotropic. In the last years there have been a lot of improvements

in grain oriented silicon steel manufacturing. As a result there are grain oriented silicon steel materials that

can have quite low loses in the lamination direction compared to other materials in the iron based alloys

group. Silicon steel material that is isotropic is called Non-oriented silicon steel.

Iron-nickel alloys can be made of different proportions of nickel. Today there are three different types

of iron-nickel alloys that are produced. The alloy with 80 % Ni content has very high initial permeability

(typically up to 100 K). Alloy with 50 % Ni has the highest saturation flux density in the group of iron-nickel

alloys (close to 1.6 T). And the alloy with 36 % Ni has the highest electrical resistivity in this group, also

this material has one of the smallest thermal expansion coefficient of all the magnetic materials used today.

Iron-cobalt alloys are usually made of 50 % Co. These materials have extremely high saturation flux

density (up to 2.2 T). They are used for electromagnet pole tips.

Today the greatest manufacturers of iron based alloys are Magnetics [10], Vacuumschmelze [11] and

TDK [12]. Table 2.2 gives some of the iron based alloys produced by Magnetics and lists some of their

magnetic properties. As the table shows, iron based alloys have quite high saturation flux density and offer

quite a wide range of different initial permeability values. Saturation flux density of 50 % cobalt alloy has

in fact the highest saturation flux density value among all commercially available soft magnetic materials.

In addition, these materials typically have Curie temperature greater than 450◦C and can therefore be used

at high temperatures (typically up to 150◦C in order to have a high margin to Curie temperature). Due to the

fact that these materials have been manufactured and used for many years now, their manufacturing process

has developed so that they are relatively inexpensive compared to other magnetic materials. In addition

cores of various sizes and shapes are readily available. Cores made of iron based alloy laminations are not

brittle. They are quite strong and not sensitive to mechanical wear.

7](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/b2c598c0-acc4-4f16-a555-962d4c8820c3-160325211659/85/Final_report-21-320.jpg)

![CHAPTER 2. MAGNETIC MATERIALS OVERVIEW AND COMPARISON

Cores are formed from metal ribbons, where laminations are electrically insulated. This is achieved by

coating the metal ribbon with a thin layer of electrically insulating material. Materials that also have bind-

ing properties (behave like glue) are used so that the laminations would stick together after core formation.

Toroids are then simply formed by winding the coated ribbon tape. For other core shapes (such as E shapes

for example), the core formation process is a bit more complex. For these cores building parts are formed

(parts of the shape that can be easily made by stacking laminations – like I shape for example) and then

these building parts are glued together. The laminations from which the cores are formed have defined eddy

current loses, Curie temperature, saturation flux density, mechanical and thermal properties. However, for

most of the materials the BH curve can be modified and therefore, initial permeability and core loses can be

controlled before the cores are formed.

The process in which the final BH curve of the material is formed is called annealing. In this process the

cores are heated up to high temperature, while at the same time they are exposed to external magnetic field.

During this process, final steps of crystallization in the laminations take place and depending on how long

this process lasts and what was the direction of the external magnetic field, the final BH loop is shaped. If the

lines of the external magnetic field are orthogonal to the core laminations (transversal field annealing), the

final BH curve has more round or elongated shape and when the external magnetic field is parallel to core

laminations (longitudinal field annealing), final BH curve has square shape. Figure 2.2 shows three typical

BH loop shapes that can be obtained. Nickel and cobalt alloys always need to be annealed. The same goes

square round elongated

Figure 2.2: Different BH curve shapes obtained by annealing [9].

for grained oriented silicon steel. However, there are some types of iron–silicon alloys (non-oriented silicon

steel) whose BH curve can not be altered by annealing.

After annealing the laminations and stacking them to form the cores, the cores can be considered fin-

ished. They have all the magnetic, mechanical and thermal properties well defined. However, often these

cores are further processed in order to make their use easier. This is done by further coating the cores (al-

though for iron based alloys cores often come without any coating). The most usual coating material is

nylon or plastic. Often the cores are stored in aluminum case which can be coated or not. All this is done

to give further mechanical support for the laminated core and to better facilitate automated core winding.

Figure 2.3 illustrates manufacturing process for cores made of iron based alloys.

9](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/b2c598c0-acc4-4f16-a555-962d4c8820c3-160325211659/85/Final_report-23-320.jpg)

![CHAPTER 2. MAGNETIC MATERIALS OVERVIEW AND COMPARISON

Alloy material

mixing and melting

Raw materials:

Fe, Si, Ni, Co

Hot & cold

metal rolling

Liquid

metal

0.02 – 6.4 mm

tick metal

ribbon

Core winding and

insulating

laminations

Finished coresAnnealing process

Cores consisting of many

Thin, electrically isolated

laminations

Fe-Ni and

Fe-Co alloys,

Grain oriented

silicon steal

Non-oriented silicon steal

Figure 2.3: Iron based alloy cores – manufacturing process.

2.3 Powder Iron

Classification and properties

Powder iron cores are made from very small particles of iron (or other materials containing iron) that are

bound together and electrically isolated. This significantly reduces electrical conductivity of the material (10

to 100 times compared to iron based alloys) and hence eddy current losses are reduced. The fact that cores

are made of small isolated particles means that these cores have an air gap that is distributed throughout

the core. The distance between the particles (or the thickness of isolation between them) determines the

size of the distributed air gap and also the permeability of the material. A with a wide range of different

permeability are offered.

According to [2], iron powder cores were patented and their production began at the beginning of the

20th century. Since that time, manufacturing process of iron powder cores has not changed much, but the

materials used have been thoroughly researched and improved. Today iron powder cores are extensively

used in many fields of power electronics and electrical engineering.

According to their chemical composition all powder iron materials can be divided into 4 groups:

• Molypermalloy (MPP)

• High flux (HF)

• Sendust

• Pure iron powder

Here one clarification is in order. We refer to the whole group as powder iron in this thesis because of

historical and consistency reasons. However, as can be seen pure iron powder is only one subgroup, while

also other materials are classified as powder iron. Due to the fact that the pure iron powder appeared first

and as the manufacturing process is very similar for all the subgroups, in literature all these materials are

10](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/b2c598c0-acc4-4f16-a555-962d4c8820c3-160325211659/85/Final_report-24-320.jpg)

![CHAPTER 2. MAGNETIC MATERIALS OVERVIEW AND COMPARISON

Material Chemical comp. Curie temp. [◦C] Initial perm. Saturation flux density [T]

MPP 80%Ni 20%Fe 450 14 – 550 K 0.7

High Flux 50%Ni 50%Fe 360 14 – 160 K 1.5

Sendust 85%Fe 9%Si 6%Al 740 26 – 125 K 1

Pure Iron Powder 100%Fe 770 4 – 100 K 0.5 – 1.4

Table 2.4: Iron powder materials (data taken from [2] and [4]).

MPP High flux Sendust Iron Powder

Core loss Lowest Moderate Low High

Perm. vs. DC bias Better Best Good Good

Temperature stability Best Very Good Very Good Fair

Relative cost High Medium Low Lowest

Table 2.5: Comparison of different iron powder materials (adapted from [4]).

referred as powder iron [1], [2]. So the same group name is kept in this thesis.

Molypermalloy (MPP) powder cores are made of 80 % nickel and 20 % iron. These cores can have

extremely high initial permeability (up to 550 K). In addition this material has the smallest loses compared

to other iron powder materials. However, the saturation flux density is smaller than for other materials.

Also, its relative cost is the highest in this group. These cores are mainly used for in-line noise filters, high

Q filters and resonant circuits [4].

High flux (HF) powder cores are made of 50 % nickel and 50 % iron. They have the highest saturation

flux density in the group (twice higher than MPP). However, they have higher core loses when compared to

MPP. Main applications of this material are for switching regulator inductors, in-line noise filters, fly back

transformers, power factor correction (PFC), and pulse transformers [4].

Sendust powder cores are made of 85 % iron, 9 % silicon and 6 % aluminum. This material has high

saturation flux density (1 T). It has losses lower than HF and a price that is lower both than prices for MPP

and HF. One of the advantages of this material is that it has almost no magnetostriction which makes it

useful in applications operating at audible frequencies [4].

Pure iron powder cores are made from 100 % iron particles. This was the first, material to be produced

and used in this group. This material has high saturation flux density and is cheaper compared to all three

materials mentioned before. However, it also has much higher losses. This material is mostly used for

electromagnetic interference filters and low-frequency chokes in switched-mode power supplies [5]. Table

2.4 lists some of the magnetic properties of these materials.

Table 2.5 summarizes advantages and disadvantages of different iron powder materials.

Biggest manufacturers of powder iron cores are Magnetics and Micrometals [13]. Furthermore, there

is a great number of smaller companies producing powder iron cores with almost the same specifications

as for the cores from these two manufacturers. The main advantage of these materials is that they have a

high saturation flux density, offer a great variety of initial permeability values (even up to 550 K), and have

lower losses compared to iron based alloys (although pure iron powder has loses that are comparable to loses

of iron based alloys). In addition, all the materials apart from pure iron powder have more than 10 times

lower electric conductivity and therefore much lower eddy current loses. Because of all this, these materials

are well suited for high frequency applications. They are relatively inexpensive and cores are available in

11](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/b2c598c0-acc4-4f16-a555-962d4c8820c3-160325211659/85/Final_report-25-320.jpg)

![CHAPTER 2. MAGNETIC MATERIALS OVERVIEW AND COMPARISON

Advantages Disadvantages

+ High saturation flux density Bsat (typ. in the

range 0.8 to 1.5 T)

+ Wide initial permeability range (typ. 300 up

to 550 K)

+ Low core losses (only for certain materials)

(typ. 0.02 up to 250 W/kg @ 10 kHz, 0.5 T)

+ Low audio noise due to magnetostriction

+ Inexpensive

+ Cores produced in many different shapes

– High electric conductivity (typ. 2·104 to 1.5·

106 S/m)

– Can not stand high temperatures (typ. oper-

ating temperature < 110◦C)

– Fragile and sensitive to mechanical stress

– Brittle

– No large cores available

Table 2.6: Advantages and disadvantages of iron powder cores.

many shapes. However, big cores are not available. In addition, magnetostriction is quite low (and for

some material types almost not existing), so there is no audio noise problem. One of the advantages often

mentioned by manufacturers is that these materials exhibit soft saturation (no abrupt change in the slop of

the BH curve when saturating), which can be a great advantage in certain applications [4], [5].

Although these materials have lower electric conductivity than iron based alloys, it is still quite high

compared to ferrites and amorphous based alloys. In addition, due to the way the cores are manufactured

they can not stand very high temperatures. The main reason for this is that binding materials used to form the

cores are very sensitive to high temperatures. Therefore, exposing cores to high temperatures for long time

significantly reduces material lifetime. Manufacturers usually give a maximal temperature value that does

not affect the lifetime of the material (typically in the range of 90 to 110◦C [4],[5]). Furthermore, the cores

are quite sensitive to mechanical stress and can easily break. Table 2.6 lists advantages and disadvantages

of powder iron materials.

Manufacturing process

Manufacturing process for iron powder cores is not complex, and has not changed too much since the time

these materials were produced for the first time. This contributes to their relatively low price. Manufacturing

process starts with raw material preparation. For pure iron powder, iron with low carbon content is used.

For other materials, metals consisting of appropriate proportion of nickel and iron or silicon and iron are

used. These raw materials are then milled to obtain the powder with uniform particle size. Typical size of

powder particles after milling is in the range of 0.5 – 15 µm.

The next step in manufacturing process is the creation of the isolation layer around each of the particles.

This is achieved by treating the powder with acids, which creates a layer of oxide around each particle.

The amount of acid used determines the thickness of electrically isolating oxide layer around particles. On

the other hand this thickness determines the size of the distributed air gap (and therefore material initial

12](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/b2c598c0-acc4-4f16-a555-962d4c8820c3-160325211659/85/Final_report-26-320.jpg)

![CHAPTER 2. MAGNETIC MATERIALS OVERVIEW AND COMPARISON

permeability) as well as the electrical conductivity of the material. Therefore, by controlling the amount of

acids added, it is possible to control the size of the air gap and electric conductivity. In this process various

acids are used. The acid to be used to get the best performance is still a topic of extensive research.

After the powder has been treated with appropriate amount of acids, cores are formed from the powder.

This is done by adding binding materials and by pressing. Mostly used binding material is resin binder,

which can not stand high temperature. This is the main reason for lower maximal operating temperature

that these materials have compared to other magnetic materials. However, ways on how to improve binding

material properties are constantly researched and it is reasonable to expect improvements in this aspect of

the manufacturing process. Cores are finally formed by pressing the powder mixed with binding materials.

Cores formed in such a way are not very strong and are quite sensitive to mechanical wear. This is the main

reason why there are almost no big iron powder cores available, as they would break very easy.

Due to this disadvantage, if non coated cores would be used, parts of the core would start to fall off due

to external mechanical influences (during the processes of core packaging, transportation and eventually

winding). Therefore, iron powder cores always need to be coated. Most usual coatings are epoxy coating

and parylene coating. Both these materials are sort of plastics that are electrical isolators. Figure 2.4

illustrates the steps in the manufacturing process of powder iron cores.

Material milling

Raw materials:

Fe with low carbon

content or other

materials made of

Fe and Ni or Si

Treatment with

acids

Iron powder

Iron powder

oxide

Adding binders

and forming cores

by pressing

Finished cores

Finishing

(core coating)

Iron powder

cores

Figure 2.4: Iron powder cores – manufacturing process.

2.4 Amorphous and Nanocrystalline Alloys

Amorphous alloys are made of iron or cobalt and materials like boron (B) and silicon. These alloys have

special chemical, mechanic and magnetic properties. Atoms in their structure are in complete disorder and

there is no regular crystal structure that is characteristic for normal metals. Such amorphous structure is

typical for liquids, molten metal, or glass. Therefore, amorphous alloys are often called metallic glasses [2].

These alloys are produced in a form of tin ribbons directly from melt in a process of rapid solidification.

Cores are then formed by winding electrically isolated ribbons.

Nanocrystalline alloys are two phase materials. They are made of an amorphous minority phase in which

ultra fine Fe-Si crystals are embedded. The typical crystal size is 10 –15 nm. Amorphous phase makes some

20 – 30 % of nanocrystalline material, which gives typical distance between crystals of about 1 – 2 nm [7].

Nanocrystalline alloy cores are made of amorphous alloy cores which are subject to crystallization during

13](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/b2c598c0-acc4-4f16-a555-962d4c8820c3-160325211659/85/Final_report-27-320.jpg)

![CHAPTER 2. MAGNETIC MATERIALS OVERVIEW AND COMPARISON

annealing process. Figure 2.5 illustrates the difference between normal crystalline structure characteristic

for metals and amorphous and nanocrystalline structure.

Normal crystalline structure

characteristic for metals

Amorphous structure Nanocrystalline structure

Figure 2.5: Comparison between normal, amorphous and nanocrystalline structure [11].

Both material groups are quite new. Amorphous alloys were discovered in the late sixties and their com-

mercial production began in the seventies. Nanocrystalline alloys were discovered at the end of eighties-

beginning of nineties and their commercial production began at the end of nineties. The possibilities for

improving the properties of these materials as well as their manufacturing process are topics of active re-

search.

Amorphous alloys are usually classified into two groups based on the metal that dominates the alloy

content:

• Iron based amorphous alloys

• Cobalt based amorphous alloys

Iron based amorphous alloys have iron as their main constituent. These materials have quite high saturation

flux density (up to 1.6 T) and find many applications both at low and high frequencies. At low frequencies

they are used for high efficiency industrial transformers. According to [1] transformers made of this mate-

rial achieve efficiency of up to 99.5 % due to their low loses. In high frequency range these materials are

mainly used for fly back and push-pull transformers, active power factor correction common mode chokes

and power supply inductors. Main manufacturer of iron based amorphous alloys is Metglas [14].

Cobalt based amorphous alloys mainly contain cobalt. These alloys have much lower saturation flux

density compared to iron based alloys (typically around 0.7 T). In addition, they are much more expensive,

as cobalt is more expensive than iron. These materials are mainly used for anti-theft devices, magnetic field

sensors, magnetic shielding and magnetic switches. Cobalt based amorphous alloys are mainly produced

by Metglas and Vacuumschmelze. There is also a number of smaller companies that offer amorphous cores

with identical specifications as for the ones from Metglas.

Nanocrystalline alloys are usually consisting of many elements in different proportions. Some of the

mostly used materials are Finmet (from Metglas) which has chemical formula Fe73.5Cu1Nb3B9, Vitrop-

erm (from Vacuumschmelze) with chemical formula Fe73.5Cu1Nb3B7 and Nanoperm (from Magnetec [15])

14](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/b2c598c0-acc4-4f16-a555-962d4c8820c3-160325211659/85/Final_report-28-320.jpg)

![CHAPTER 2. MAGNETIC MATERIALS OVERVIEW AND COMPARISON

Material Chemical composition Curie temp. [◦C] Init. perm. Sat. flux density [T]

Amorphous Alloys

2605SC 81%Fe 13.5%B 3.5%Si 370 1.5 K 1.5 – 1.6

2605SA1 Fe based alloy 370 20-35 K 1.56

2714A 66%Co 15%Si 4%Fe 205 2 K 0.5 – 0.65

Vitrovac 603 Co based alloy 205 3 K 0.8

Nanocrystaline Alloys

Vitroperm Fe73.5Cu1Nb3B7 460 30 – 80 K 1.0 – 1.2

Nanoperm Fe73.5Cu1Nb3B7 600 0.5 – 100 K 1.2

Finmet Fe73.5Cu1Nb3B9 570 30 – 100 1.23

Table 2.7: Amorphous and nanocrystalline alloys (data taken from [2] and [14]).

which has the same chemical composition as Vitroperm. These materials generally have lower saturation

flux density when compared to iron based amorphous alloys, but higher when compared to cobalt based

alloys. Furthermore, due to the fact that they contain FeSi crystals, they have higher electrical conductivity

than amorphous alloys. However, these materials offer very wide range of initial permeabilities. In fact they

have the highest product of initial permeability and saturation flux density among all the magnetic materials.

This means that magnetic components made of these materials have the smallest dimensions compared to all

other magnetic materials. Main applications of nanocrystalline cores are common mode chokes, magnetic

amplifiers and precise current sensing devices. These materials are also used for various switched mode

power transformers. Nanocrystalline materials are slowly replacing ferrites in many applications. Table 2.7

lists some amorphous and nanocrystalline alloys and gives their magnetic properties.

Using amorphous and nanocrystalline alloys has many advantages. Main advantage of amorphous alloys

is that amorphous crystal structure leads to much lower electrical conductivity than with metals that have

normal crystal structure. In addition these materials have quite low hysteresis losses. All of these makes

them very suitable for use at high frequencies. Moreover these materials offer quite high saturation flux den-

sity (up to 1.6 T). Cores made of amorphous ribbons are not brittle and they are not sensitive to mechanical

wear. Moreover, these cores can withstand constant working temperatures up to 130◦C.

However, these cores are very expensive compared to cores made from more traditional magnetic mate-

rials. In addition, there are not many different core shapes available. Cores are mainly produced as toroids

and U shaped cores. Magnetostriction is very strong with these materials and therefore they produce very

high noise at audio frequencies. Also these materials do not offer very wide initial permeability range and

there are no amorphous cores with high permeability available. Main advantages and disadvantages of amor-

phous alloys are listed in Table 2.8.

Nanocrystalline alloys also have quite high saturation flux density. However, it is slightly lower than

for amorphous alloys (typically up to 1.2 T). In the last years it has been realized that using other elements

than silicon to form crystals inside amorphous phase could result in higher saturation flux density. This is a

topic of intensive research and it is reasonable to expect improvements in this aspect of nanocrystalline alloy

production. These materials also offer wide range of initial permeability values. In fact it is recognized that

using these materials results in cores that are much smaller compared to cores made from all other magnetic

materials. These materials can also stand high temperatures up to 130◦C. Contrary to amorphous alloys,

due to the fact that they contain FeSi crystals, these materials emit little or no noise due to magnetostriction.

However, the presence of FeSi crystals has also negative sides. The greatest one is that electric conduc-

15](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/b2c598c0-acc4-4f16-a555-962d4c8820c3-160325211659/85/Final_report-29-320.jpg)

![CHAPTER 2. MAGNETIC MATERIALS OVERVIEW AND COMPARISON

not available. Table 2.9 lists main advantages and disadvantages of nanocrystaline alloys.

Manufacturing process

Manufacturing processes for amorphous and nanocrystalline alloys are similar. This is because nanocrys-

talline alloys are obtained out of amorphous materials by initializing crystallization process during anneal-

ing. Same as for other material groups, manufacturing process starts with raw material preparation. De-

pending on the chemical structure of the final alloy different elements are used. Amorphous alloys contain

mainly Fe, B and Si. For nanocrystalline alloys Cu and niobium (Nb) need to be added. Cu is added as its

atoms serve as starting points around which Fe-Si crystals are later formed, while Nb prevents the crystals

of growing too much. Similar as for iron based alloys, raw materials are melted and turned into liquid metal.

However contrary to manufacturing process of iron based alloys, where the ribbons were made from the

molten metal that cooled down slowly, amorphous ribbons are made from molten metal in the process of

rapid solidification.

During rapid solidification process, amorphous alloys are obtained from molten metal which is cooled

down very quickly (typical cooling speed is 106 K/s) which does not allow crystals to be form. Because of

this fast solidification, atoms behave like frozen and retain similar structure as they had when the metal was

in liquid state. In this process the molten metal is first heated up to 1300◦C by an induction heater. The melt

is then projected through a ceramic nozzle directly onto a fast spinning (around 100 km/h) water cooled

roller whose temperature is always controlled to be around 20◦C. As a result amorphous ribbon which is

typically 0.02 mm thick and can have width in the range of 17 – 25 mm is obtained. Figure 2.6 illustrates

rapid solidification process.

Figure 2.6: Rapid solidification process [11].

17](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/b2c598c0-acc4-4f16-a555-962d4c8820c3-160325211659/85/Final_report-31-320.jpg)

![CHAPTER 2. MAGNETIC MATERIALS OVERVIEW AND COMPARISON

Material Chemical comp. Curie temp. [◦C] Initial perm. Saturation flux density [T]

K MnZn ferrite > 230 1.5 K 0.48

R MnZn ferrite > 230 2.3 K 0.5

P MnZn ferrite > 230 2.5 K 0.5

F MnZn ferrite > 250 5 K 0.49

W MnZn ferrite > 125 10 K 0.43

H MnZn ferrite > 125 15 K 0.43

Table 2.10: Ferrite materials produced by Magnetics (data taken from [2]).

brittle and very hard materials. They are composed of various oxides, having iron oxide as their main

constituent. General chemical formula of ferrites is MeFe2O3, where Me represents one or more divalent

transition metals. Depending of what Me actually is, ferrites can be classified in two groups [2]:

• Manganese-zinc ferrites (Me = MnZn)

• Nickel-zinc ferrites (Me = NiZn)

Manganese-zinc ferrites are more widely used than nickel-zinc ferrites, and they are produced in greater

variety of different materials. They have higher initial permeability, but also higher electrical conductivity

than nickel-zinc ferrites. They are mainly used in applications where the frequency is less than 2 MHz.

Nickel-zinc ferrites have extremely low electrical conductivity (typically 10−5 S/m) . This makes them

suitable for applications with frequencies from 1 – 2 MHz up to several hundreds of MHz. However, these

materials have lower initial permeability than manganese-zinc ferrites.

Main manufacturers of ferrite cores are Magnetics, Epcos [16] and Feroxcube [17]. There is also a great

number of smaller companies producing ferrites. Table 2.10 lists some of the most popular ferrite materials

from Magnetics. As can be seen from the table, ferrites have quite low saturation flux density compared to

other magnetic materials. In addition, they do not offer wide range of initial permeability values, as very

high permeability is not available. In addition, mechanical properties of ferrites are not so good. They are

very brittle materials that are extremely hard to process and cut. Also they do not have very high Currie

temperatures and their magnetic properties significantly depend on temperature.

Nevertheless, ferrites have very low electric conductivity compared to all other magnetic materials (typi-

cally in the range 1·10−5 −1 S/m). Also, they have quite low loses. All of these makes them well suited for

high frequency applications. This is the main reason why ferrites are so widely used in modern day power

electronics. In addition, ferrite cores are available in many different shapes and sizes at relatively low price.

Ferrites do not suffer from problems with producing noise due to magnetostriction. Table 2.11 lists all the

advantages and disadvantages of ferrites.

Manufacturing process

Raw materials in the ferrite core production process are oxides and carbons of main constituents. The first

phase in manufacturing process is weighting and mixing of the raw materials which are in the form of

powder. The mixing can be dry, or water can be added in order to make a slurry mass that is then mixed

19](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/b2c598c0-acc4-4f16-a555-962d4c8820c3-160325211659/85/Final_report-33-320.jpg)

![CHAPTER 2. MAGNETIC MATERIALS OVERVIEW AND COMPARISON

Advantages Disadvantages

+ Inexpensive

+ Available in many different core shapes and

sizes

+ Low core losses (typ. 5 up to 100 W/kg @

10 kHz, 0.5 T)

+ Almost no audio noise due to magnetostric-

tion

+ Very low electric conductivity (typ. in the

range of 1 · 10−5 to 1 S/m)

– Low saturation flux density Bsat (typ. in the

range 0.3 to 0.5 T)

– No wide range of initial permeability avail-

able (typ. 0.1 K up to 20 K)

– Not so high Currie temperatures, magnetic

properties deteriorate significantly with tem-

perature increase

– Very strong and extremely hard to process

and cut

– Brittle

Table 2.11: Advantages and disadvantages of ferrites.

more easily. In case when wet mixing is used, water needs to be first evaporated before the next step in

the manufacturing process. Mixed raw materials are then exposed to high temperatures in what is called

calcining process. The main purpose of this phase is to eliminate any impurities present in the mixture as

the quality of the final product greatly depends on the presence of impurities in the raw material. Mixed

powder mass is then milled in order to obtain powder with uniform particle sizes. Organic binders are

added to this powder and cores are formed by pressing. Pressing is done by using combined action of

top and bottom punches in a cavity so that a part with uniform density is formed. Today, tools that allow

simultaneous production of many cores exist. Also, quite complex core shapes can be produced nowadays.

Since the finished ferrite cores are so hard that they can not be further cut or shaped, the final core shape has

to be formed during this phase. As a result of pressing, so called green cores are obtained. In order to obtain

ferrite cores, green cores need to be subjected to sintering.

Sintering is a process characteristic for ceramic production. It is the most important step in the cycle

of ferrite manufacturing as during this process ferrite material achieves its final mechanical and magnetic

characteristics. During sintering process equilibrium of time, temperature and atmosphere is achieved in

order to turn green core into ferrite material. Sintering consists of three phases. The first one is the burnout

phase in which the temperature is gradually increased from room temperature up to 800◦C. The atmosphere

in which this is done is air. The main purpose of this sintering phase is to burn out any left impurities,

binders or lubricants and to eliminate any moisture. Next step is the actual sintering process in which

the temperature is further increased up to 1000 − 1500◦C depending on the actual material. While the

temperature is increased, non oxidizing gas is introduced into the chamber in order to reduce the content

of oxygen in the atmosphere. During the last phase of sintering, in which the cores are cooled down, the

oxygen level is reduced to zero. Figure 2.8 illustrates a typical sintering cycle. During sintering, the size of

the cores is reduces by 20 – 30 %. Therefore, green cores always need to be larger than the end products.

However the actual amount of core shrinkage is not certain and therefore ferrite cores always have up to

±2 % uncertainty on their final size [6]. Figure 2.9 illustrates the manufacturing process for ferrites.

20](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/b2c598c0-acc4-4f16-a555-962d4c8820c3-160325211659/85/Final_report-34-320.jpg)

![CHAPTER 2. MAGNETIC MATERIALS OVERVIEW AND COMPARISON

Figure 2.8: Sintering process cycle [8].

Material

preparation and

weighting

Raw materials:

Oxides and

carbons of main

constituents

Milling to specific

grain size

Raw materials

with right

proportion Powder with

uniform grain

size

Adding organic

binders and forming

cores by pressing

Finished cores

Finishing

(core coating)

Green cores

Sintering

process

Figure 2.9: Manufacturing process of ferrites.

21](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/b2c598c0-acc4-4f16-a555-962d4c8820c3-160325211659/85/Final_report-35-320.jpg)

![Chapter 3

Core Loss Modeling

As already said, designing magnetic components, such as transformers and inductors, requires some specific

knowledge about the electrical and magnetic properties of the magnetic material that is used. One of the

most important properties that should be known is the core loss behavior. Core loss depends on the mag-

netic material used, core geometry and size, shape of the exciting flux density waveform, excitation signal

frequency, magnetic field strength DC bias and operating temperature. Therefore, it is an important factor

that determines the choice of magnetic material, core size and shape.

In modern day power electronics it is very important to reduce the size and increase efficiency of power

electronic systems. Since transformers and inductors occupy a lot of space and produce considerable amount

of losses, ways to reduce loses in these components have become an important research issue. The first step

in making any improvement in this direction is to derive an accurate core loss model. However, core loss

modeling is not a trivial task and is still a topic of active scientific research.

This chapter gives a short introduction on physical origin of core loses. It describes some of the most

usual ways to model core loses that are used today and compares different modeling approaches, giving

advantages and disadvantages for each method. At the end of the chapter an accurate and easy to use, hybrid

core loss modeling approach is described.

Physical Origin of Losses

In order to understand physics behind core losses, one has to look at the process of magnetization. This pro-

cess occurs due to alignment of electron magnetic moments under the influence of external magnetic field.

Each electron of the atoms in the crystal structure of magnetic material has a magnetic (orbital) moment

which is a consequence of its rotation around the atom nucleus. When an external magnetic field exists,

these magnetic moments start to orient themselves in the direction parallel to the lines of external mag-

netic field. As a result, complete atoms in the structure start behaving like small magnets that are aligned

parallel to the external magnetic field. However, the alignment of these atomic magnets does not happen

homogenously in the entire structure, but only within certain regions called ferromagnetic (or Weiss) do-

mains. These domains usually have laminar patterns and their size can vary from 0.001 mm3 to 1 mm3

[1]. Each of the domains is characterized by an overall magnetic moment which is a result of summing

together many atomic magnets. Domain magnetic moments are oriented in such a way that the total energy

23](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/b2c598c0-acc4-4f16-a555-962d4c8820c3-160325211659/85/Final_report-37-320.jpg)

![CHAPTER 3. CORE LOSS MODELING

is kept minimal. This means that the adjacent domains have opposite magnetic moments. Weiss domains

are mutually separated by the so called domain (or Bloch) walls. Organization of the Weiss domains in a

magnetic material is illustrated in Figure 3.1.

Figure 3.1: Illustration of Weiss domains and domain wall movement [18].

In order to change global magnetization of the material, domain walls need to move. Therefore, magne-

tization change is highly localized and not uniform through the material. This means that the magnetization

change is spatially distributed. In addition, presence of imperfections in magnetic materials causes rapid

movements of the domain walls, the so called Barkhausen Jumps. Therefore, the magnetization is also

discrete in time, as the local velocity of the domain walls is different than the change rate of the external

magnetic field. Discrete nature of magnetization in terms of space and time means that there is a rapid local

change of magnetization even if the external magnetic field is changing very slowly. Associated with these

changes are local energy losses caused by eddy currents and spin relaxation. Globally, loses are determined

by local and time distribution of these local losses. In addition, macroscopic eddy current losses contribute

to total core losses. They are caused by currents in the material induced by the external magnetic field.

Therefore, core losses on a macroscopic scale are caused by the damping of domain wall movements by

eddy currents and spin relaxation on a microscopic scale and macroscopic eddy current losses.

Ways to Model Core Losses

Detailed knowledge on physical background of core losses does not help much in their modeling. Losses

depend on very chaotic space and time distribution of domain wall movement and therefore it is almost

impossible to derive physical equations that could precisely model losses. Since the model derivation from

the first principles is not possible, there are several other approaches to model core losses developed by the

electrical engineering community. Models that are often found in the literature and that are used in practice

can be divided into four groups:

24](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/b2c598c0-acc4-4f16-a555-962d4c8820c3-160325211659/85/Final_report-38-320.jpg)

![CHAPTER 3. CORE LOSS MODELING

1. Hysteresis models (like Preisach and Jiles-Atherton)

2. Empirical equations (based on Steinmetz Equation)

3. Loss–separation approach

4. Loss map

Hysteresis models are mathematical core loss models that find their bases in the physical processes behind

core losses. They can be generally divided into two groups. Jiles-Atherton model [21] is based on macro-

scopic energy calculation. It consists of a differential equation that can model core losses. Parameters of the

model need to be determined iteratively. The advantage of this model is that it leads to good understanding

of the magnetization process. The main drawback of the model is that there is a great number of parameters

that need to be estimated. Second model is the so called Preisachs model [22]. In this model, a statistic ap-

proach is used for describing space and time distribution of domain wall movements. A weighted function is

used for representing material characteristics. The main disadvantage of this model is that the identification

of the parameters in this function is very hard. It requires great experimental effort without offering high

accuracy [18].

Empirical equations for modeling core loses are mainly based on the so called Steinmetz equation which

was formulated (in a bit different form than it is used today) more than a century ago [23]. This equation

describes core losses per unit volume as a function of excitation signal frequency and flux density amplitude:

Pv = kfα ˆBβ

, (3.1)

where Pv represents time-average power loss per unit volume in W/m3, f is the frequency of the applied

sinusoidal excitation signal in Hz and ˆB is peak induction in T. Parameters k, α and β are material dependent.

These parameters are often called Steinmetz parameters. Steinmetz equation has been widely used as a

starting point for modeling core loses for many years now. Manufacturers sometimes directly give Steinmetz

parameters as a means for design engineers to calculate core losses. Moreover, Steinmetz equation has been

widely used by electric engineers even in cases when manufacturers provide raw data on losses per unit

volume (or mass). In this case many design engineers use the data to estimate Steinmetz parameters and then

calculate the losses in operating point of interest by using equation 3.1. However, although widely accepted

and used in electrical engineering community, Steinmetz equation has three serious drawbacks. The first one

is that the parameters k, α and β are only valid for a limited frequency and flux density range. Therefore

manufacturers often provide couple of parameter sets for different ranges. However, calculating losses at the

borders of these ranges may lead to significant errors. Another big disadvantage is that Steinmetz equation

is only valid for sinusoidal excitations. This is a significant limitation when having in mind that in modern

day power electronics mainly non-sinusoidal excitation signals are used. Third disadvantage is that, by

Steinmetz equation, core losses are modeled only as a function of frequency and flux density. However,

many experimental findings show that core losses can also significantly depend on core temperature and DC

bias of the magnetic field strength [25] – [27].

There has been a lot of attempts to extend the Steinmetz equation in order to overcome these drawbacks.

Most important improvement is the one that extends the model so it can be used for greater variety of flux

density waveforms. This extension was motivated by the finding that the losses due to domain wall motion

directly depends on dB/dt. In [18] – [20], the so called improved Generalized Steinmetz Equation (iGSE)

has been introduced. According to this equation core loses per unit volume can be calculated as:

Pv =

1

T

T

0

ki

dB

dt

α

(∆B)β−α

dt, (3.2)

25](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/b2c598c0-acc4-4f16-a555-962d4c8820c3-160325211659/85/Final_report-39-320.jpg)

![CHAPTER 3. CORE LOSS MODELING

where T is the period of the exciting signal and ∆B is peak-to-peak flux density ripple. Parameters α and

β are the same parameters as used in Steinmetz equation and ki is related to the k in Steinmetz equation by

the following relation:

ki =

k

(2π)α−1 2π

0 |cosθ|α

2β−αdθ

(3.3)

The iGSE equation allows quite accurate loss estimation for a great variety of flux density waveforms.

According to this equation no losses occur when the flux remains constant. However, this contradicts ex-

perimental findings which show that core loss still exists even when the flux density is constant [28], [29].

In [28] it has been assumed that losses at constant flux density occur due to relaxation effects. These

losses are termed relaxation losses and it is assumed that they occure due to fast changes in magnetization,

when the matherial has to progresivly move towards the new thermal equilibrium. In the same work the

iGSE equation is further extended so that the relaxation losses are taken into account. Extended equation is

termed improved-improved Generalized Steinmetz Equation (i2

GSE). According to this model, core losses

per-unit-volume are calculated as:

Pv =

1

T

T

0

ki

dB

dt

α

(∆B)β−α

dt +

n

l=1

QrlPrl, (3.4)

where n represents the number of stepped voltage changes in the excitation signal, Qrl is the function that

further describes the flux density change:

Qrl = e

−qr

dB(t+)

dt

dB(t−)

dt , (3.5)

where dB(t−)/dt represents the flux density change rate before the switching, dB(t+)/dt is the flux den-

sity change rate after the switching and qr is material dependent parameter which has to be determined

experimentally. For each stepped voltage change, Prl is given by the equation:

Prl =

1

T

kr

dB(t−)

dt

αr

(∆B)βr

(1 − e−

t1

τ ), (3.6)

where t1 represents the time to the next stepped change and kr, αr, βr and τ are material dependent param-

eters that can be determined experimentally by measuring loss energy for trapezoidal flux waveforms with

different lengths of the constant flux period. Figure 3.2 shows the meaning of the variables in equations

3.4/3.5/3.6.

As can be seen, the only difference to the Equation 3.2 is that there is an additional term that should

compensate for the losses occurring due to relaxation process. With this extension, losses can be modeled

for any flux density waveform encountered in modern day power electronic systems. However, the depen-

dence of the losses on temperature and magnetic field strength DC bias is not modeled. There has been

several works on extending the Steinmetz model so that dependence on pre-magnetization can be taken into

account. In [25] a model in which ki and β in the Equation 3.2 would be modeled as functions of pre-

magnetization DC bias is proposed. However, a complete analytical model that would describe losses as a

function of frequency, flux density, DC bias and temperature still does not exist.

In loss separation approach, core loses are divided into three parts. It is assumed that losses can be

separated into static hysteresis losses (Ph), dynamic eddy-current losses (Pcl) and the so called excess losses

(Pexc):

Pv = Ph + Pcl + Pexc (3.7)

26](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/b2c598c0-acc4-4f16-a555-962d4c8820c3-160325211659/85/Final_report-40-320.jpg)

![CHAPTER 3. CORE LOSS MODELING

t1

dB(t-)/dt

dB(t+)/dt

t

B Change point for which the

contribution is calculated

Figure 3.2: Definition of variables in i2GSE model.

This model is a result of a common belief that existed in electrical engineering community for a long time

that core loses are caused by two independent physical effects: static hysteresis and eddy-currents. However,

as explained before this lacks theoretical justification, since the losses are caused by microscopic domain

wall movements and can not be so easily divided at macroscopic scale. Since modeling losses only as a sum

of these two terms can lead to very big errors, excess loss term is added in order to compensate for the error.

Analytic form only exists for calculating eddy-current loses, while other two terms need to be determined

experimentally [30]. Two main disadvantages of such a model are that it lacks physical justification and that

extraction of the model parameters can be very difficult.

Modeling approach based on loss map implies extensive core loss measurement. In this modeling ap-

proach the loss map stores information on loss per volume for many operating points described by flux

density ripple amplitude (∆B), excitation signal frequency (f), pre-magnetization DC bias (HDC) and tem-

perature (T). Measurements are usually repeated for great variety of excitation signal waveforms. Losses

for a particular working point are then calculated by interpolation between closest operating points for which

measurements are available. If measurement points are selected densely enough, this approach leads to very

accurate results. The main disadvantage is that extensive measurements are necessary in order to achieve

good accuracy. Ways to model core losses by using a loss map are described in [24] – [27].

General problem with modeling core losses is that manufacturers do not provide data which could be

sufficient to derive most of the analytic models presented here. Therefore in order to extract model parame-

ters, usually extensive measurements have to be done. At present there is no universal core loss model that

would be precise and widely accepted and used both by manufacturers and engineers. All of the modeling

approaches described above have certain disadvantages. Therefore, in order to make a precise and useful

core loss model, some of these models need to be combined. In the following section one such hybrid

model is described. It was found to be quite accurate. This model is used as a basis for building magnetic

component design environment presented in this thesis.

27](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/b2c598c0-acc4-4f16-a555-962d4c8820c3-160325211659/85/Final_report-41-320.jpg)

![CHAPTER 3. CORE LOSS MODELING

Hybrid Core Loss Model

In [31], an approach which combines loss map and i2

GSE is proposed. It is proposes that core losses should

be measured and stored in a loss map. This should be done for various operating points described by peak-

to-peak flux density ripple (∆B), excitation signal frequency (f), temperature (T) and pre-magnetization

DC bias (HDC). Measurements should be performed with sinusoidal flux waveforms for low frequencies

(less than 1 kHz) and with triangular, 50 % duty cycle flux waveform for high frequencies (above 1 kHz). In

addition, the loss map should contain the initial BH relation, which can be taken from material datasheet or

can be estimated from a measured differential BH curve. Also it is proposed that a set of parameters αr, βr,

kr, τ and qr should be contained in the loss map (these parameters are as in Equations 3.5 and 3.6). These

parameters can be estimated experimentally by measuring core losses for specific flux density waveforms.

Core losses per unit volume are then calculated by using such a loss map and the i2

GSE model.

This hybrid model can be used for calculating losses for an arbitrary flux density waveform. For instance

signals that are often found in power electronic devices today are those that consist of a fundamental, low

frequency, sinusoidal part and a high frequency, piecewise linear signal that is superimposed to it. Such flux

density waveforms are typical in power factor correction applications for example. The proposed model

is very good in modeling losses for such a complex flux waveform. The flux density waveform for which

the losses should be calculated is broken up into the fundamental waveform, which is usually sinusoidal,

and the piecewise linear flux waveform segments. The losses per unit volume are then calculated for the

fundamental and for each linear segment and then summed up in order to get total losses. For it, piecewise

linear waveforms are translated into triangular flux waveforms with same ∆B, HDC and same flux density

slope dB

dt . This has to be done in order to have correspondence with the loss map in which loss values are

stored for symmetric triangular waveforms. For each of the linear segments, an operating point is defined:

(∆B∗, f∗, H∗

DC, T∗). The loss dependence on temperature and pre-magnetization DC bias is obtained by

linear interpolation. The dependence on frequency and flux density ripple is obtained for the fundamental

(sinusoidal) signal by Equation 3.1 and for the piecewise linear segments by Equation 3.3. The necessary

parameters α, β and k (or ki) are extracted from the loss data stored in the loss map. To this end, mea-

surement points that are closest to the operating point of interest need to be identified. All together nine

measurement points are needed for interpolation. For extraction of α, β and k (or ki) three points are needed

and this has to be multiplied by three for the linear interpolation in T and HDC. First, a linear interpola-

tion in temperature and DC bias is done. This is done for all three ∆B/f pairs of interest. This leads to

losses for three points with different ∆B and f values that are close to the values of the operating point

of interest. The temperature and DC bias values as in the operating point of interest has been interpolated:

(∆B1, f1, H∗

DC, T∗), (∆B2, f1, H∗

DC, T∗), (∆B1, f2, H∗

DC, T∗). Out of these three points α, β and k (or ki)

are extracted by solving a system of three nonlinear equations (Equation 3.1 for low frequency measure-

ment data and Equation 3.2 for high frequency measurement data). The interpolation process is illustrated

in Figure 3.3. Core losses per unit volume are then calculated by Steinmetz equation in case of fundamental

and in case of piecewise linear segments by the i2

GSE equation.

It has been shown that this modeling strategy results in a very accurate loss calculation even in cases

when loss map is not very dense. Therefore, this approach offers very good accuracy at a moderate mea-

surement effort. In addition, in [31] a way for calculating losses of the complete inductors and transformers

based on this core loss modeling approach is given, i.e. it is shown how to take the core shape into consid-

eration. Furthermore, it is shown how to calculate copper losses.

28](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/b2c598c0-acc4-4f16-a555-962d4c8820c3-160325211659/85/Final_report-42-320.jpg)

![CHAPTER 3. CORE LOSS MODELING

Interpolation in temperature and pre-magnetization DC bias Interpolation in frequency and flux density ripple

Figure 3.3: Illustration of the interpolation process for the loss map data [31].

29](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/b2c598c0-acc4-4f16-a555-962d4c8820c3-160325211659/85/Final_report-43-320.jpg)

![CHAPTER 5. CORE LOSS MEASUREMENT SYSTEM

System error Way to detect

Desired signal frequency outside al-

lowed range

User enters frequency value greater than 200 kHz or smaller than

1 kHz for high frequency excitation and higher than 1 kHz or

lower than 50 Hz for sinusoidal excitation

Desired temperature outside allowed

range

User enters desired core temperature value that is higher than

160◦C or a positive value lower than 30◦C

Average current too high Reference value of the average current to be written to the DSP

is greater than 25 A

DC link voltage too high DC link voltage that should be set is higher than 450 V for high

frequency excitation and 300 V for sinusoidal excitation

DC link voltage too low DC link voltage that should be set is lower than 3 V

DC link in current limitation mode Measured current of the DC power supply is equal to 1.7 A

Unknown error There is no voltage or current on the CUT when the program

expects that excitation signal should exist

Table 5.8: List of errors that the software can detect with short explanation on how they are detected.

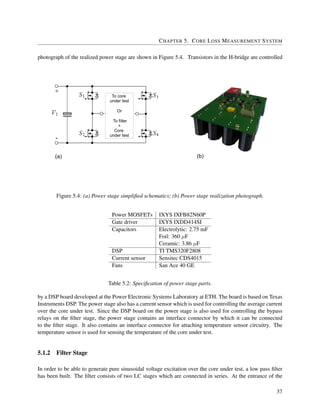

When the system is brought to the desired operating point, measurements can be taken. Before taking the

measurements, the oscilloscope has to be set. In the single operation mode, the user can set the oscilloscope

manually, or the settings can be made automatically. The button Set oscilloscope automatically is connected

to the function that does the setting. Since the losses are calculated through the integration of the BH curve,

current and voltage measurements have to be taken for exactly one period or for a time interval that is equal

to integer multiple of the signal period. Therefore, for signals that have frequencies lower than 10 kHz,

horizontal oscilloscope resolution is set so that exactly one period is visible in the oscilloscope screen. For

higher frequencies, horizontal resolution is set so that 10 full periods are visible on the oscilloscope screen.

The oscilloscope has a limited set of scales for setting the horizontal axes. Therefore, the set of frequencies

for which the automatic oscilloscope setting is possible is also limited. Table 5.9 lists frequency values for

which the automatic setting is possible. The oscilloscope vertical settings are set so that the best possible

f [kHz]

High frequency excitation 1 2 5 10 20 50 100 200

Sinusoidal excitation 0.05 0.1 0.2 0.5

Table 5.9: List of frequencies for which the automatic oscilloscope setting is possible.

resolution is obtained while still having the whole signals visible on the oscilloscope screen.

Button Get results is used for taking the measurement and calculating core losses. The function that

is connected to this button takes the current and voltage measurement from the oscilloscope and delays

measured current in order to compensate for the deskew time. Losses per unit volume are then calculated

according to the equations 5.1, 5.2 and 5.3. This is repeated three times and the actual core loss value is

taken as a mean value. Upon taking the measurements, the results box is populated with the values that

were actually measured. Measured voltage and current, as well as the calculated flux density, magnetic field

strength and core loss are stored to a temporary Matlab file. The results can then be saved permanently by

the user. In case the data is not saved, the temporary file will be overwritten after the next measurement.

56](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/b2c598c0-acc4-4f16-a555-962d4c8820c3-160325211659/85/Final_report-70-320.jpg)

![CHAPTER 6. CORE LOSS MEASUREMENT DATABASE

- 1 5 0 - 1 0 0 - 5 0 0 5 0 1 0 0

- 0 . 4

- 0 . 3

- 0 . 2

- 0 . 1

0

0 . 1

0 . 2

0 . 3

0 . 4

H [ A / m ]

B[T]

N 8 7

B H c u r v e f= 5 0 0 H z T = 6 0 ° C

in it ia l B H r e la t io n f= 5 0 0 H z T = 6 0 ° C

1 0

- 1

1 0

0

1 0

3

1 0

4

1 0

5

1 0

6

B

p p

[ T ]

P

v

[W/m3]

N 8 7

f= 5 k H z H D C = 0 A / m T = 2 3 ° C

f= 2 0 k H z H D C = 0 A / m T = 2 3 ° C

f= 5 0 k H z H D C = 0 A / m T = 2 3 ° C

2 0 3 0 4 0 5 0 6 0 7 0 8 0 9 0 1 0 0 1 1 0 1 2 0

1 0

3

1 0

4

1 0

5

T [ ° C ]

P

v

[W/m3]

N 8 7

f= 5 k H z B p p = 0 . 2 T H D C = 0 A / m

f= 2 0 k H z B p p = 0 . 2 T H D C = 0 A / m

f= 5 0 k H z B p p = 0 . 2 T H D C = 0 A / m

0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8

0 . 2 0 3 5

0 . 2 0 4

0 . 2 0 4 5

0 . 2 0 5

0 . 2 0 5 5

0 . 2 0 6

0 . 2 0 6 5

0 . 2 0 7

0 . 2 0 7 5

0 . 2 0 8

t

1

[ u s ]

E[J]

N 8 7

B p p = 0 . 1 T t 2 = 2 5 u s T = 2 3 ° C

Figure 6.4: Examples of some plots made for N87 ferrite material from EPCOS. Top left plot shows the BH

curve of the material; top right shows core losses as a function of peak-to-peak flux density ripple for

different signal frequency values; bottom left shows core loss as a function of temperature at different

signal frequencies; bottom right shows dependence of loss energy from zero voltage time in a sweep

measurement done with three level voltage excitation.

70](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/b2c598c0-acc4-4f16-a555-962d4c8820c3-160325211659/85/Final_report-84-320.jpg)

![Chapter 7

Magnetic Component Design Software

The magnetic component design software already existed before the start of this master thesis project. In

this project it has been connected to the core loss measurement database in order to complete the design

environment. Also the software was slightly improved by adding the relaxation loss model that did not

exist before. This chapter gives a short overview of the design software and describes the extensions of the

software in detail.

The magnetic component design software can be used for calculating core losses for four different core

geometries. The hybrid core loss model described in Chapter 3 is used. Also, winding loss calculation for

solid wire is possible, with the prospect of extending the software so that calculation would be possible for

litz wire or foil windings. Winding losses are calculated by using the models for skin effect and proximity

effect losses. In addition, based on the calculated losses, the software can calculate expected temperature

for both the core and the windings. The software is also capable of calculating inductance values for four

implemented core geometries. Excitation signals for which losses and temperature can be calculated can be

selected from a list of predefined signal waveforms (where square, sinusoidal and trapezoidal flux density

waveforms are available) or they can be imported from circuit simulation software such as Simplorer or

Matlab. Figure 7.1 shows how the graphical user interface of the design software looks like. Detailed

description of the design software can be found in [32].

7.1 Software Extensions

Magnetic component design software has been extended so that it can use the data from the database as a

loss map. In order to form the loss map, the loss measurements from the database are fused together into a

hyper-matrix. This is done by using methods of the class for interacting with the database. Used methods are

listed in Appendix F. The software also uses the information on the initial permeability of the material that

is stored in the database. In addition, initial BH relation that the software needs for inductance calculation

is extracted from one of the material BH curves stored in the database. Although, such an approximation of

the initial BH relation is not very accurate in the area where the strength of magnetic field is close to zero,

it is the best approximation that can be made from a dynamic BH loop measurement. This is necessary for

materials for which manufacturers do not provide the initial relation data. Initial BH relation is calculated

by assigning to each H value, the mean of the two B values that correspond to it in the BH curve. Figure

71](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/b2c598c0-acc4-4f16-a555-962d4c8820c3-160325211659/85/Final_report-85-320.jpg)

![CHAPTER 7. MAGNETIC COMPONENT DESIGN SOFTWARE

- 1 5 0 - 1 0 0 - 5 0 0 5 0 1 0 0 1 5 0

- 0 . 4

- 0 . 3

- 0 . 2

- 0 . 1

0

0 . 1

0 . 2

0 . 3

0 . 4

H [ A / m ]

B[T]

N 8 7

M a t e r ia l B H c u r v e

E x t r a c t e d in it ia l B H r e la t io n

Figure 7.2: BH curve for EPCOS N87 ferrite with initial BH relation extracted from the curve.

For a particular sweep operating point defined by the flux density peak-to-peak ripple (BPP) and time length

of positive and negative voltage period (t2), this equation becomes:

∆E = kr

BPP

t2

αr

(Bpp)βr

(7.3)

The value for ∆E can be calculated from the measurement data by subtracting the measured energy for

t1 = 0 from energy measured for biggest t1 in the sweep measurement. Figure 7.3 illustrates the way to

calculate ∆E. By forming equation 7.3 for three different operating points, a system of three nonlinear

equations with three unknown parameters is formed. The relaxation loss model parameters are obtained by

solving this system and by using Equation 7.1 for calculating τ.

The parameter qr can be extracted from the sweep measurement data obtained with two level voltage

excitation with variable duty cycle. This parameter is used to correct the error occurring when the core

losses are calculated by only using the iGSE for low duty cycle values. If we denote the core loss calculated

by only using the iGSE, for a given duty cycle value from the sweep by PiGSE(D), we will see that for low

duty cycle values actually measured results are higher than the calculated values. On the other hand, the

measured losses are always lower than the upper loss limit given by the equation:

Pmax(D) = PiGSE(D) + Pr, (7.4)

where Pr represents the contribution of the relaxation loss, given by Equation 3.6. According to the i2

GSE

model, core losses for a given duty cycle are calculated by the following equation:

P(D) = PiGSE(D) + e−qr

D

1−D Pr (7.5)

73](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/b2c598c0-acc4-4f16-a555-962d4c8820c3-160325211659/85/Final_report-87-320.jpg)

![CHAPTER 7. MAGNETIC COMPONENT DESIGN SOFTWARE

0 10 20 30 40 50 60

0

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

t

1

[µs]

E[µJ]

∆B = 50mT, t

2

= 10µs

∆B = 100mT, t

2

= 10µs

∆B = 100mT, t2

= 5µs

τ

2∆E.

Figure 7.3: Dependence of measured sweep energy from zero voltage time period with illustration on how

to calculate ∆E. Shown measurement results are for N87 EPCOS material.