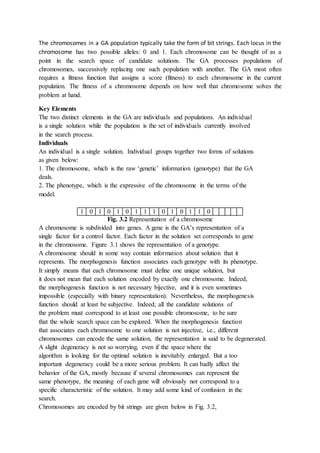

Genetic algorithms (GAs) were developed in the 1960s-1970s by Holland and his colleagues to study natural adaptation. GAs use operations like selection, crossover and mutation to evolve solutions to problems iteratively. Selection allows fitter solutions to reproduce more, crossover combines parts of solutions, and mutation randomly changes parts of solutions. Together, these operations mimic natural evolution to help GAs explore the search space and find optimal solutions.