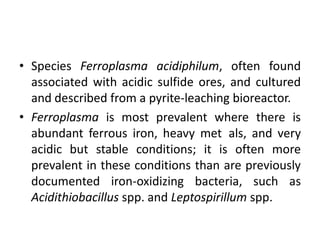

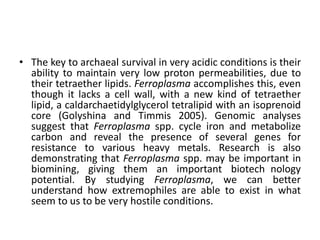

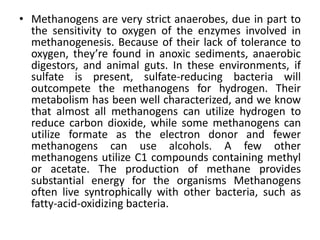

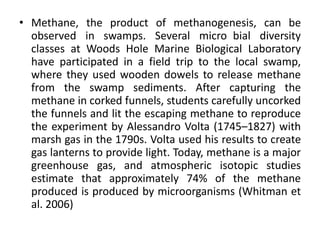

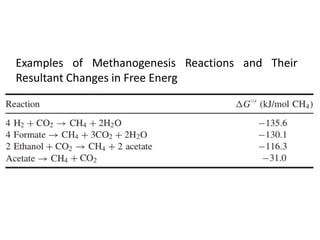

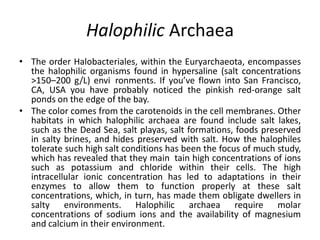

Extremophiles are organisms that thrive in extreme conditions of pH, temperature, or salinity. Some bacteria and archaea live in extremely hot or cold temperatures, while others live in very salty or acidic/alkaline environments. One example is Nanoarchaeum equitans, a dwarf archaeon that lives in temperatures between 70-98°C. Methanogens are a group of archaea that produce methane through anaerobic metabolism. Halophilic archaea thrive in hypersaline environments through adaptations like transport proteins that pump ions across their cell membranes. Acidophiles maintain pH homeostasis through active proton pumps and passive DNA/protein repair systems that protect against acid damage.