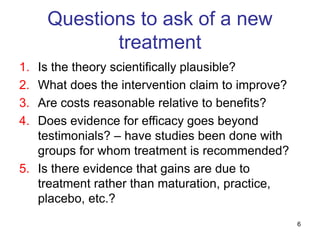

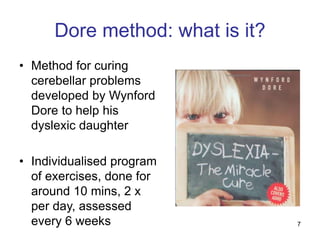

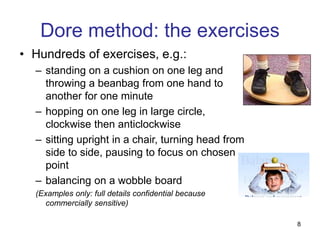

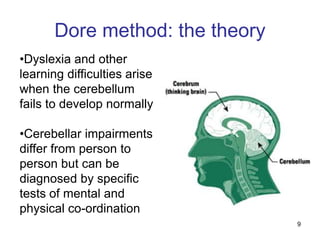

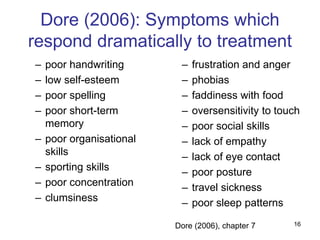

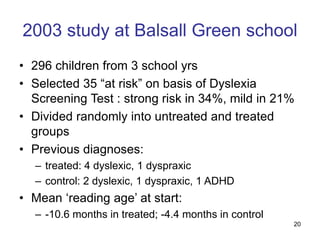

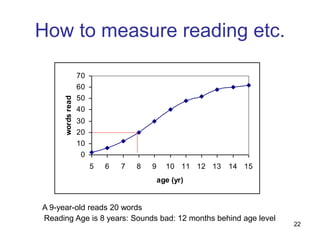

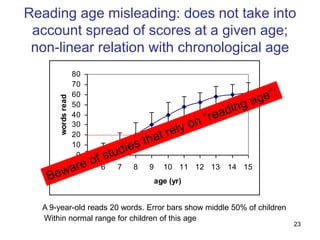

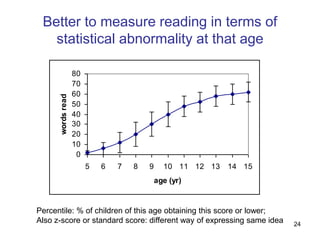

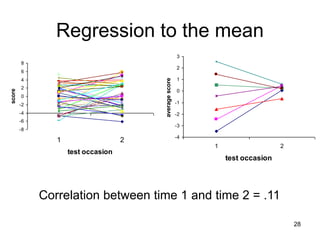

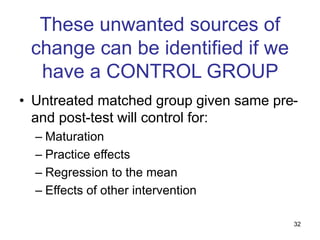

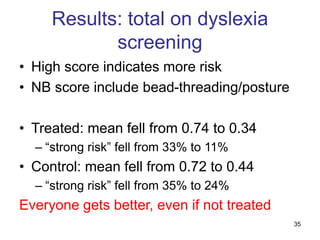

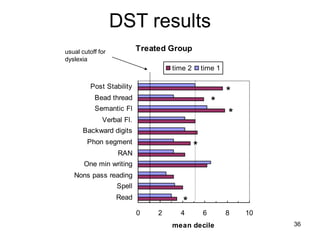

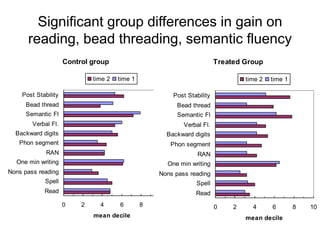

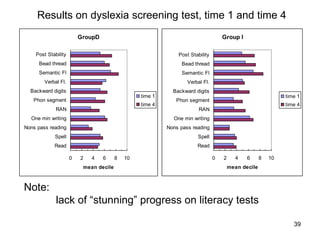

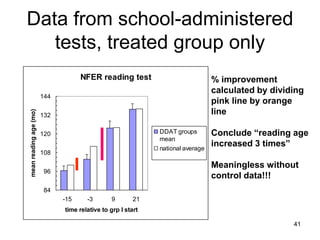

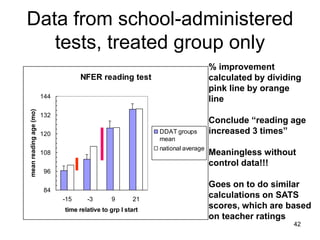

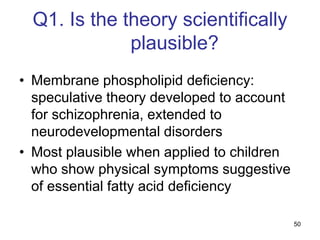

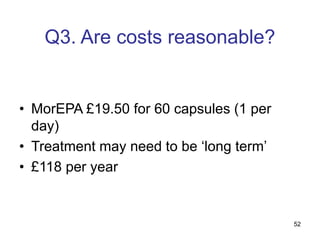

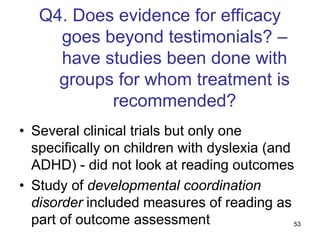

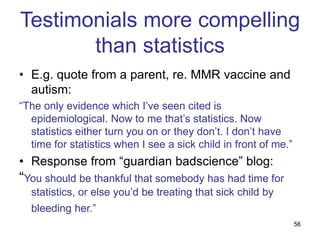

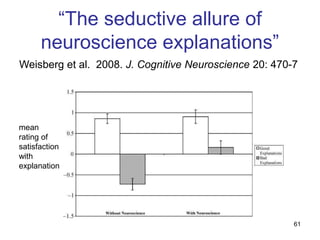

The document discusses various approaches to treating reading disabilities, particularly dyslexia, highlighting traditional phonological interventions and alternative methods like the Dore method and fish oil supplementation. It raises critical questions regarding the scientific plausibility of these methods, their claimed benefits, and the validity of their supporting evidence, ultimately questioning the efficacy of motor training and alternative treatments without robust control groups. It concludes that while some treatments may seem promising, the actual improvements in literacy may not be significantly attributable to the interventions based on available data.