The document explores ethical issues in biotechnology, focusing on the distinctions between ethics and morality, the importance of ethical considerations in various fields such as agriculture and medicine, and the debate surrounding modern biotechnological advancements. It discusses different ethical approaches, including normative and descriptive ethics, alongside principles of bioethics like beneficence, non-maleficence, autonomy, and justice. Additionally, it highlights the public's varying moral concerns and acceptance towards biotechnology-related topics through surveys conducted across different cultures.

![81

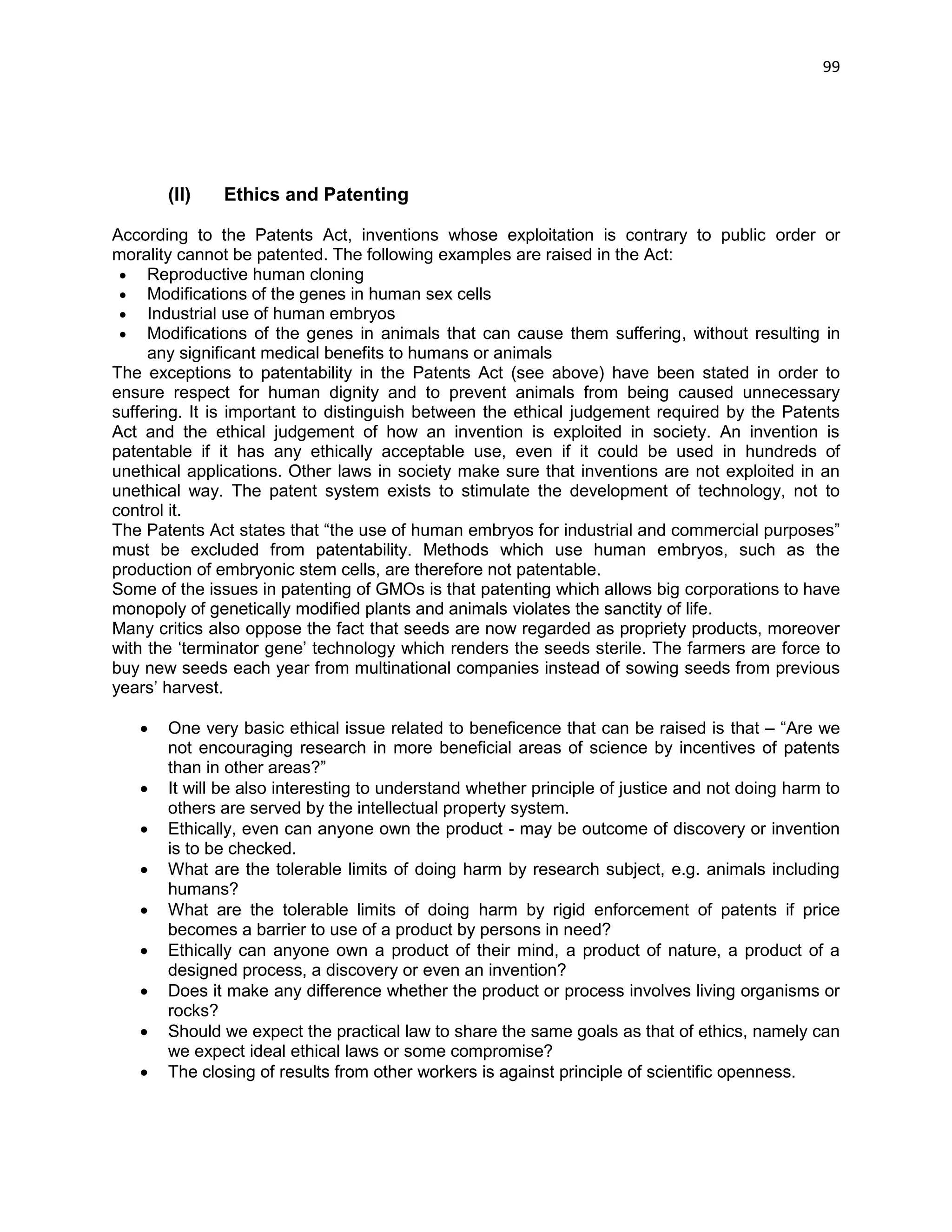

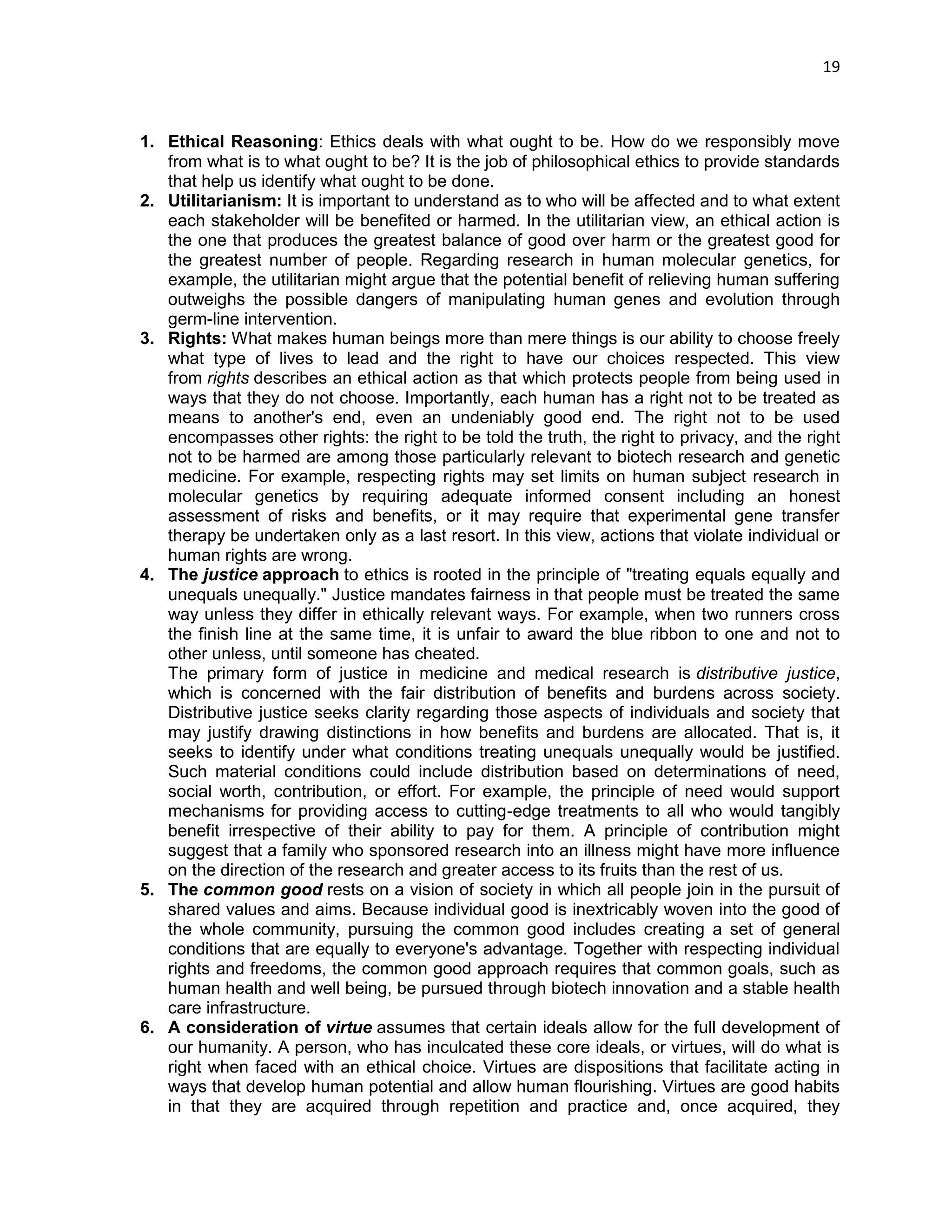

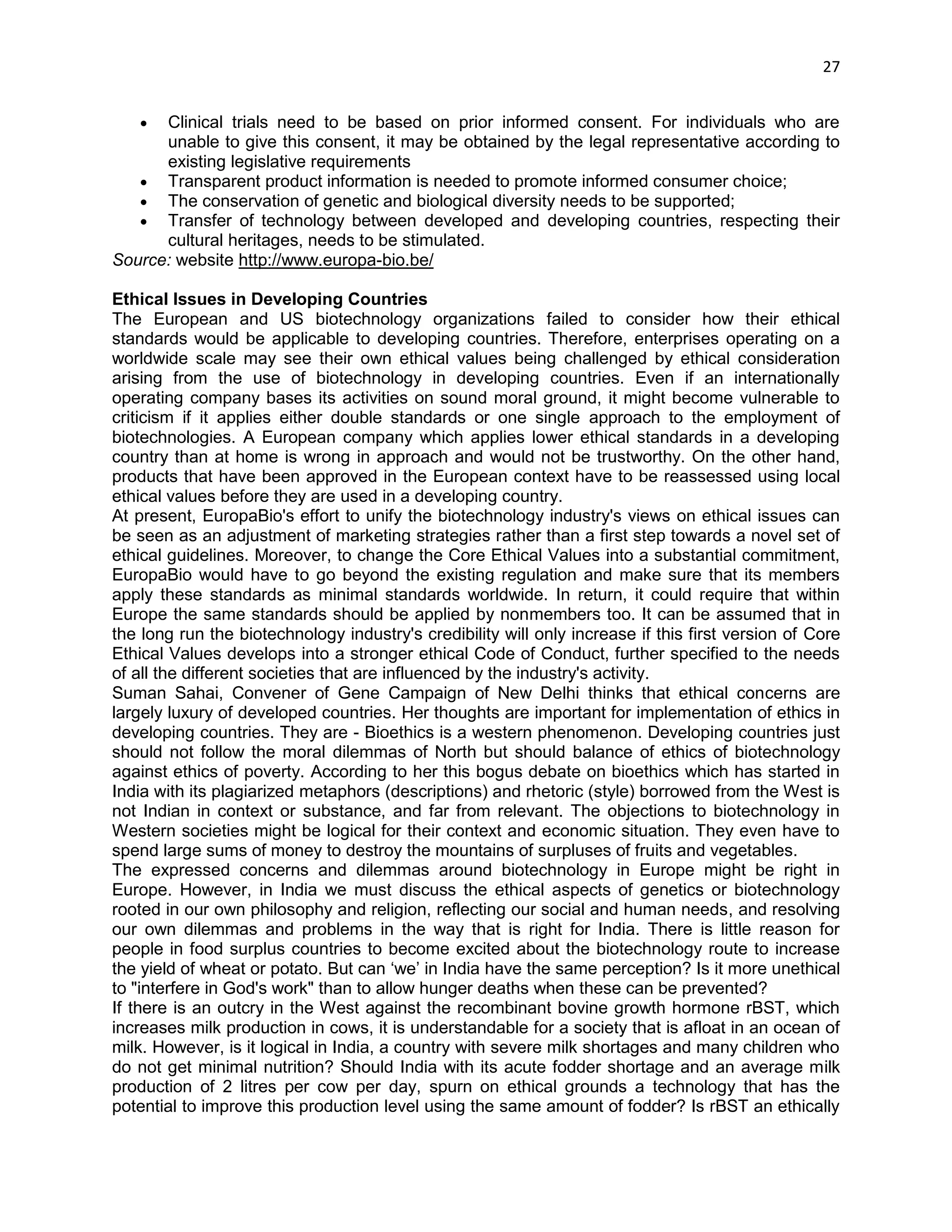

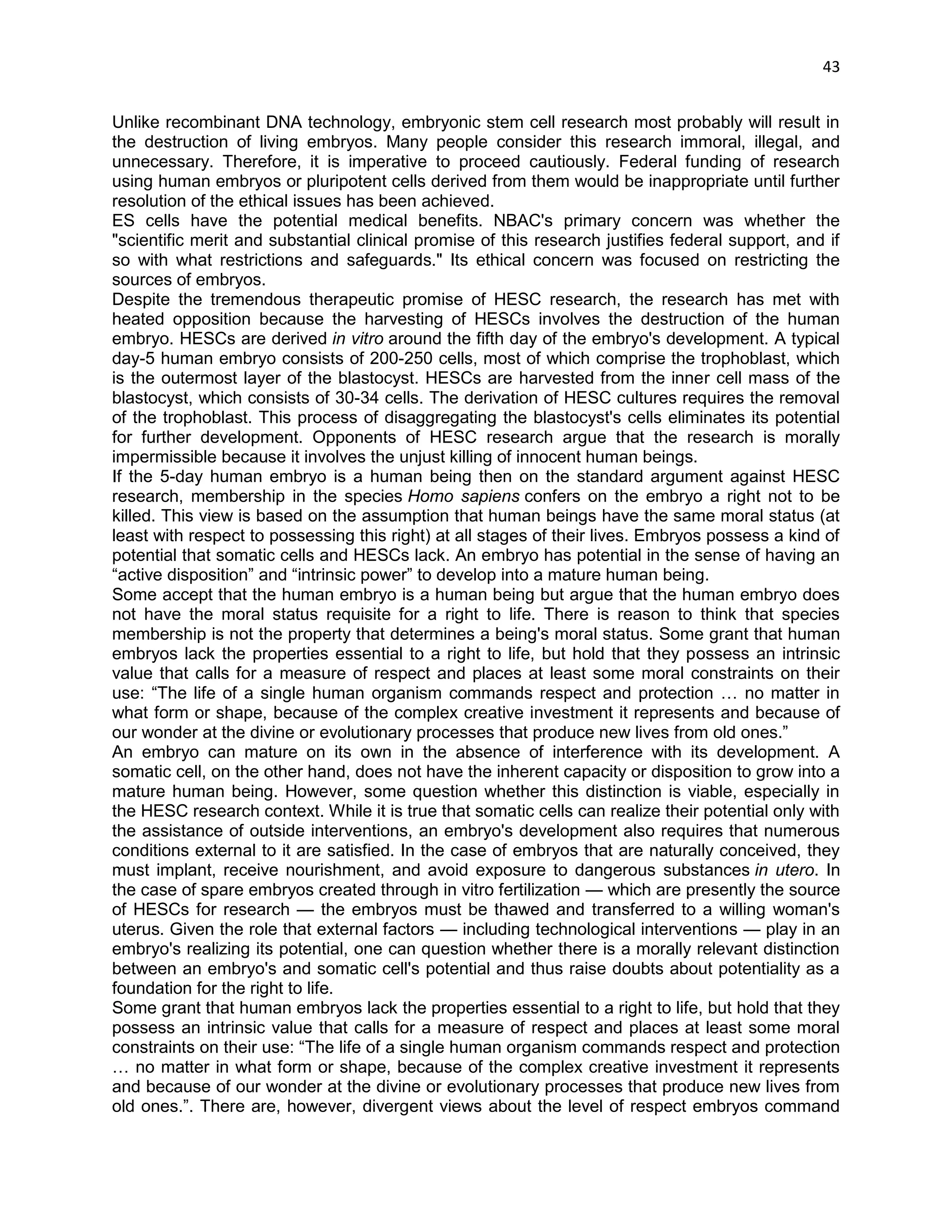

In the post-marketing era, phase IV trials are done to collect additional information on the drug‘s addition risks and benefits and study its optimal use. Even after a drug is available for prescription, its use is carefully monitored and unexpected side effects are reported.

Phase Zero

Development costs for new drugs are rising dramatically. A large factor in the increased costs is that many drugs are failing late in development [Phase III trials]. The approval rate for innovative new drugs is declining. Some of these failures can be attributed to poor or poorly understood pharmacokinetic (PK) parameters and the fact that regardless of how well characterized a compound's behavior is in vitro or in animal models, these systems are imperfect representatives of human physiology. Some 30%–40% of new drugs fail due to poor performance at the transition from animal to human trials. To mitigate the risks and costs associated with late-stage failures, companies have recently looked to a new method of testing compounds earlier in humans: Phase Zero. These micro-dosing studies involve the administration of sub-pharmacologic or sub-therapeutic doses (on the order of micrograms) of a drug candidate to humans, who are monitored to generate a preliminary ADME or PK profile. It is hoped that giving companies earlier, safer data on how the drug is processed in the body will dramatically accelerate the more expensive clinical testing phase. Although the Phase Zero approach is not appropriate for all compounds, when thoughtfully applied, Phase 0 techniques help developers select only the most promising drug candidates for further development by mitigating the risk of failure due to poor PK and bioavailability characteristics in humans. For early-stage pharma and biotech firms, Phase Zero testing is a cost-effective way to increase value by providing first-in-human data earlier in the development/investment cycle.

European Agency for the Evaluation of Medicinal Products (EMEA) put out a position paper in early 2003 which supported the use of microdosing as nonclinical safety studies in support of further clinical studies, and it defined a microdose as 1/100th the dose required to present a pharmacologic effect, and no more than 100 grams. FDA went a step beyond the EMEA paper by issuing a draft guidance document relating to exploratory Investigational New Drug (IND) applications and which included reference to the use of microdosing as part of this process.

The EMEA position paper deals only with microdose studies that allow only single, nonpharmacologic doses and provide information only on pharmacokinetics. The FDA guidance also discusses the option of performing repeat-dose clinical studies using doses designed to induce pharmacological effects. These latter types of studies provide much more information regarding potential efficacy.

The new guidance should save companies millions of dollars in development costs in short order. In the traditional IND, he explains, preclinical toxicology and safety requirements cost more than $650,000 and can take as long as six months to perform. However, a human microdosing experiment can be initiated with less than $150,000 in preclinical toxicology and safety testing, which can be completed within one month.

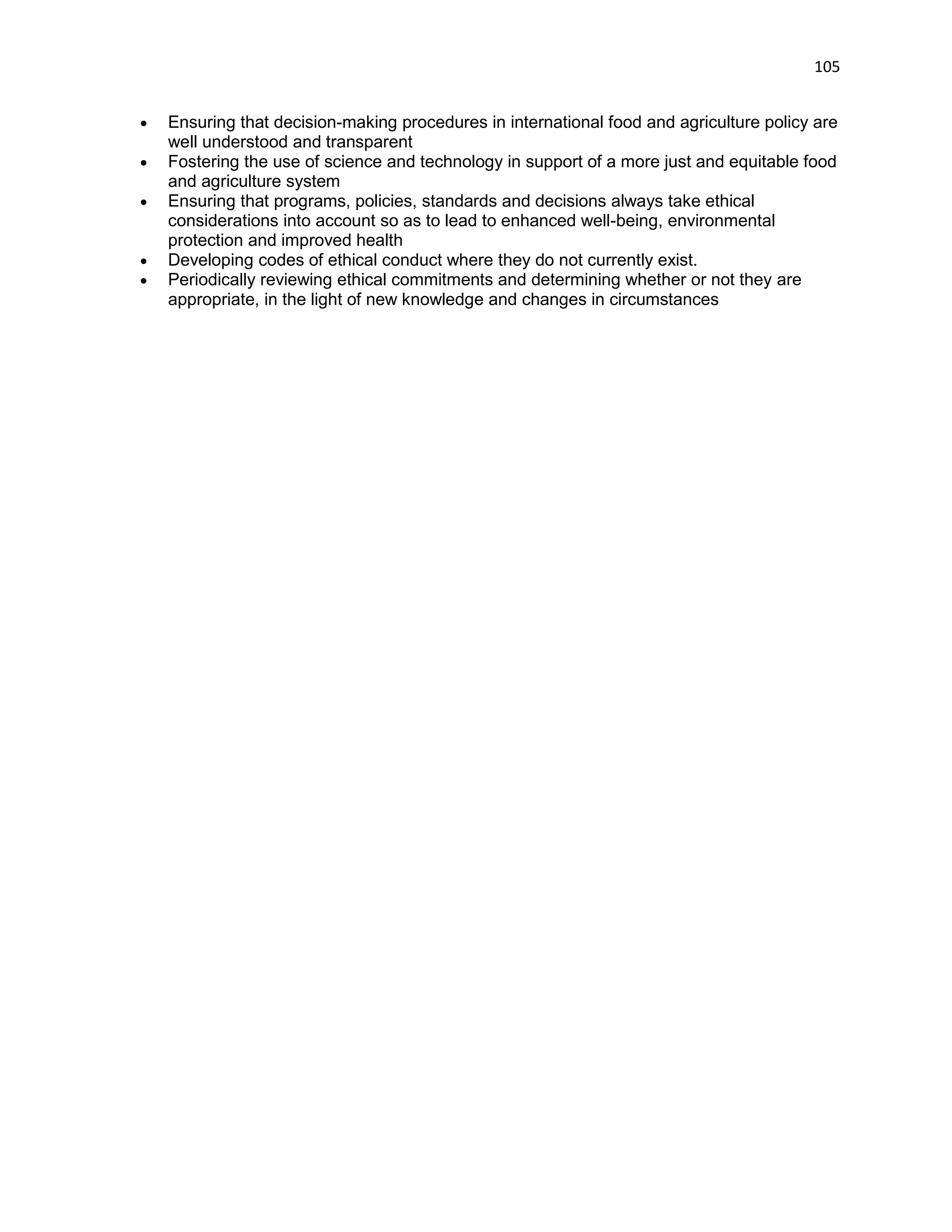

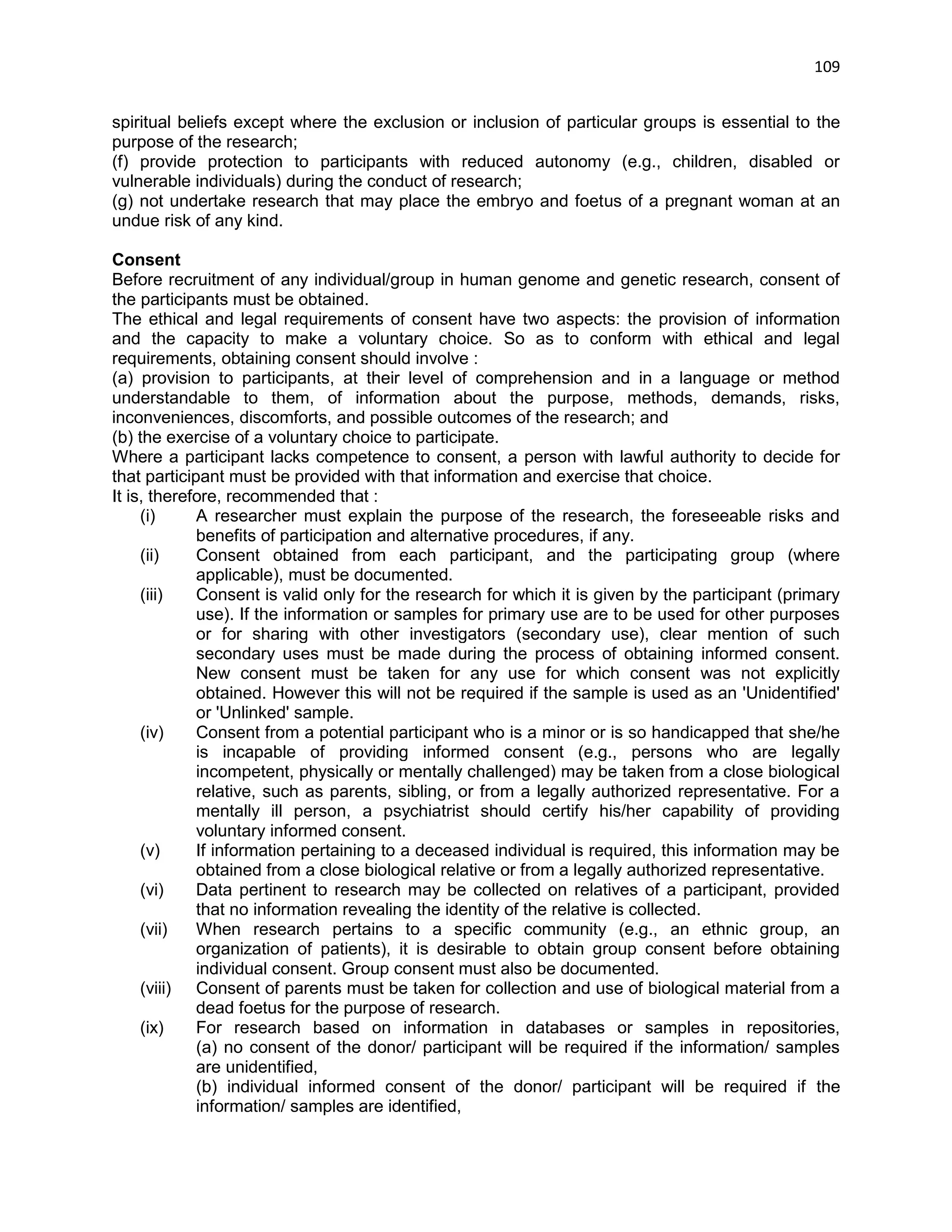

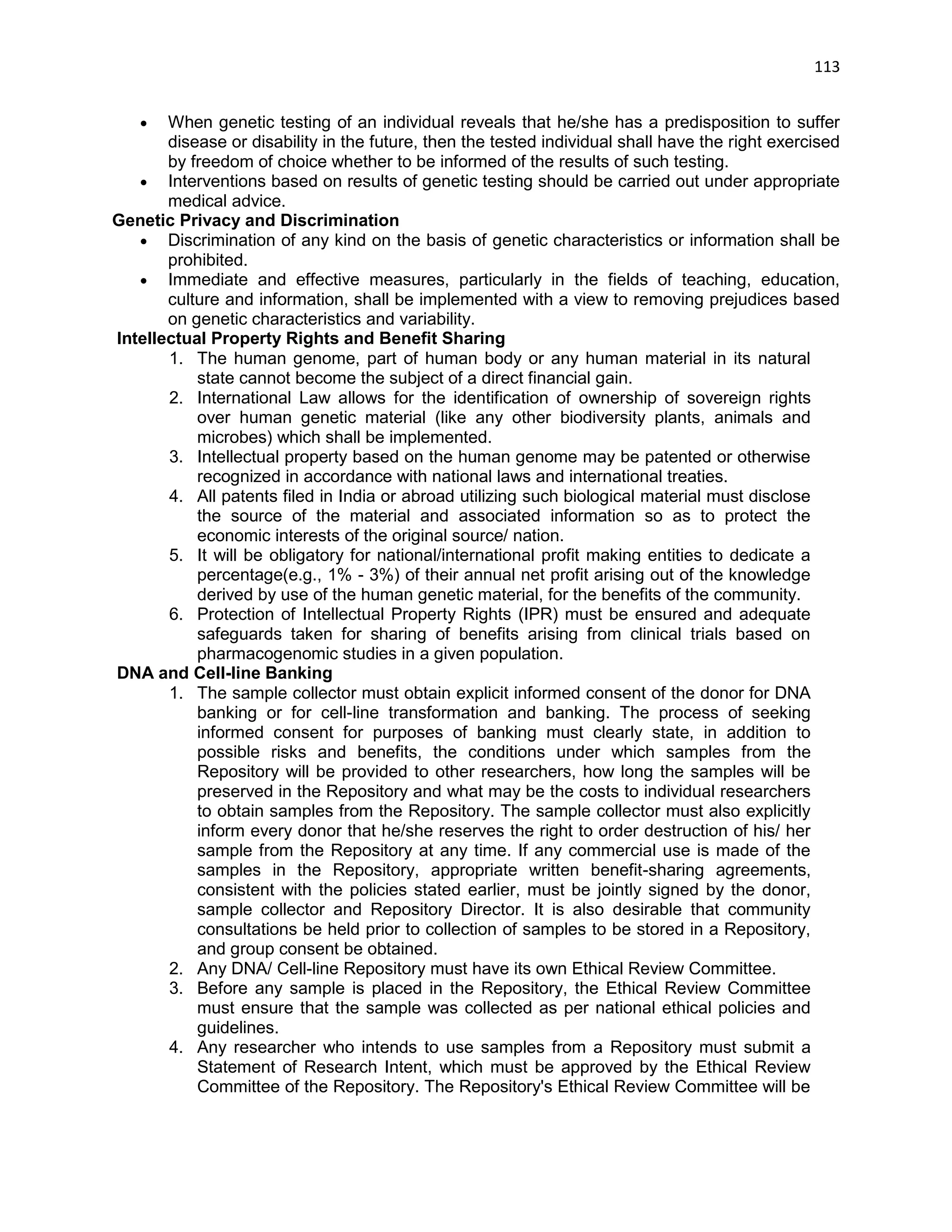

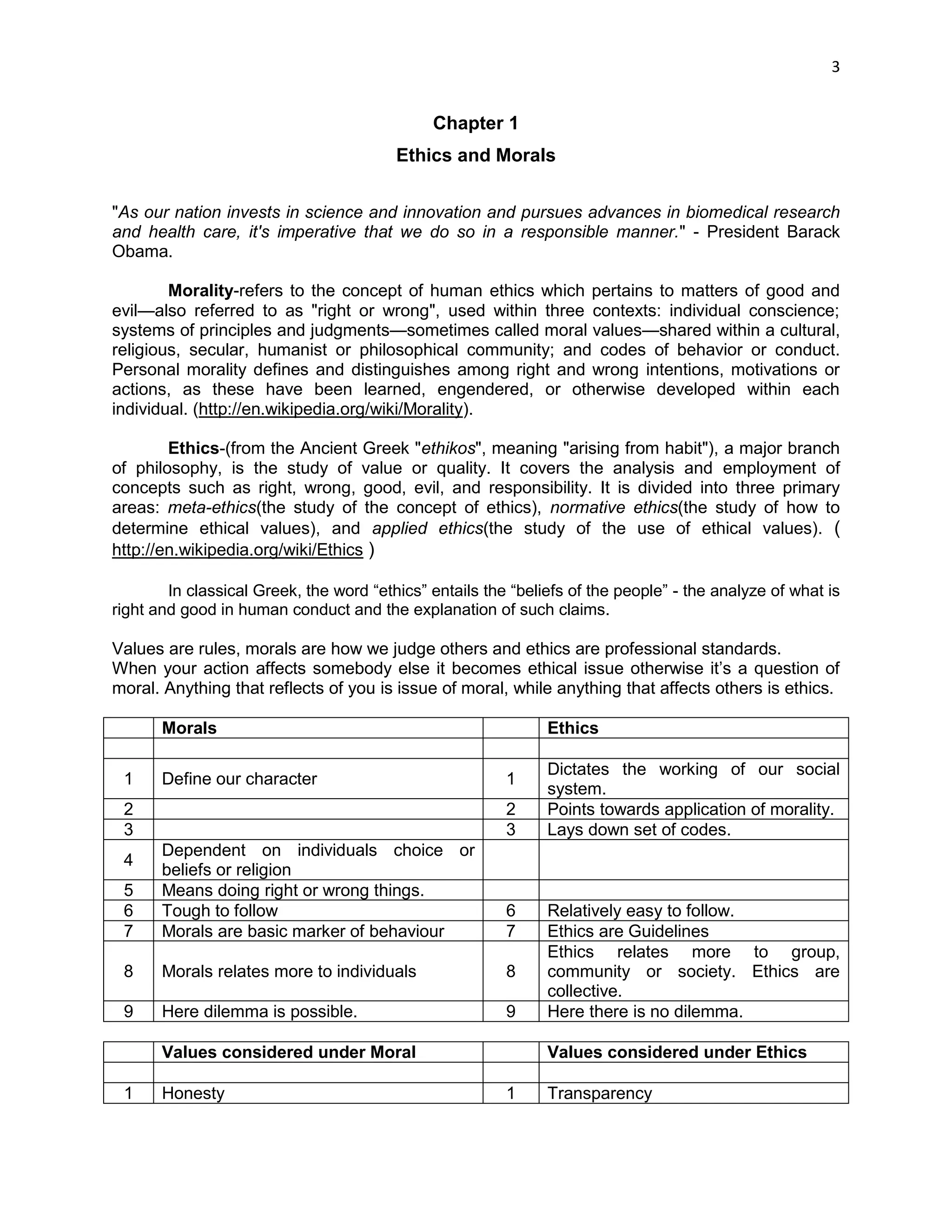

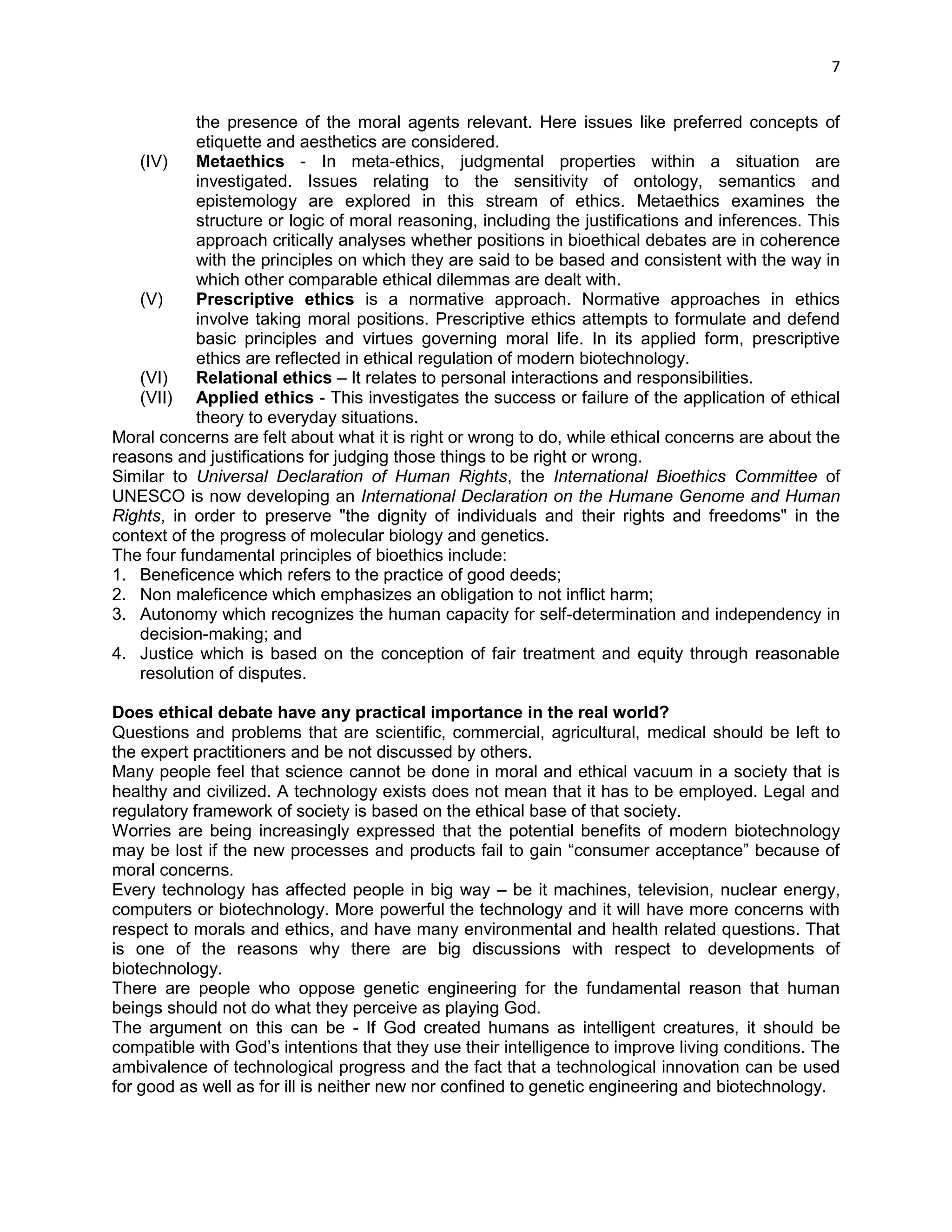

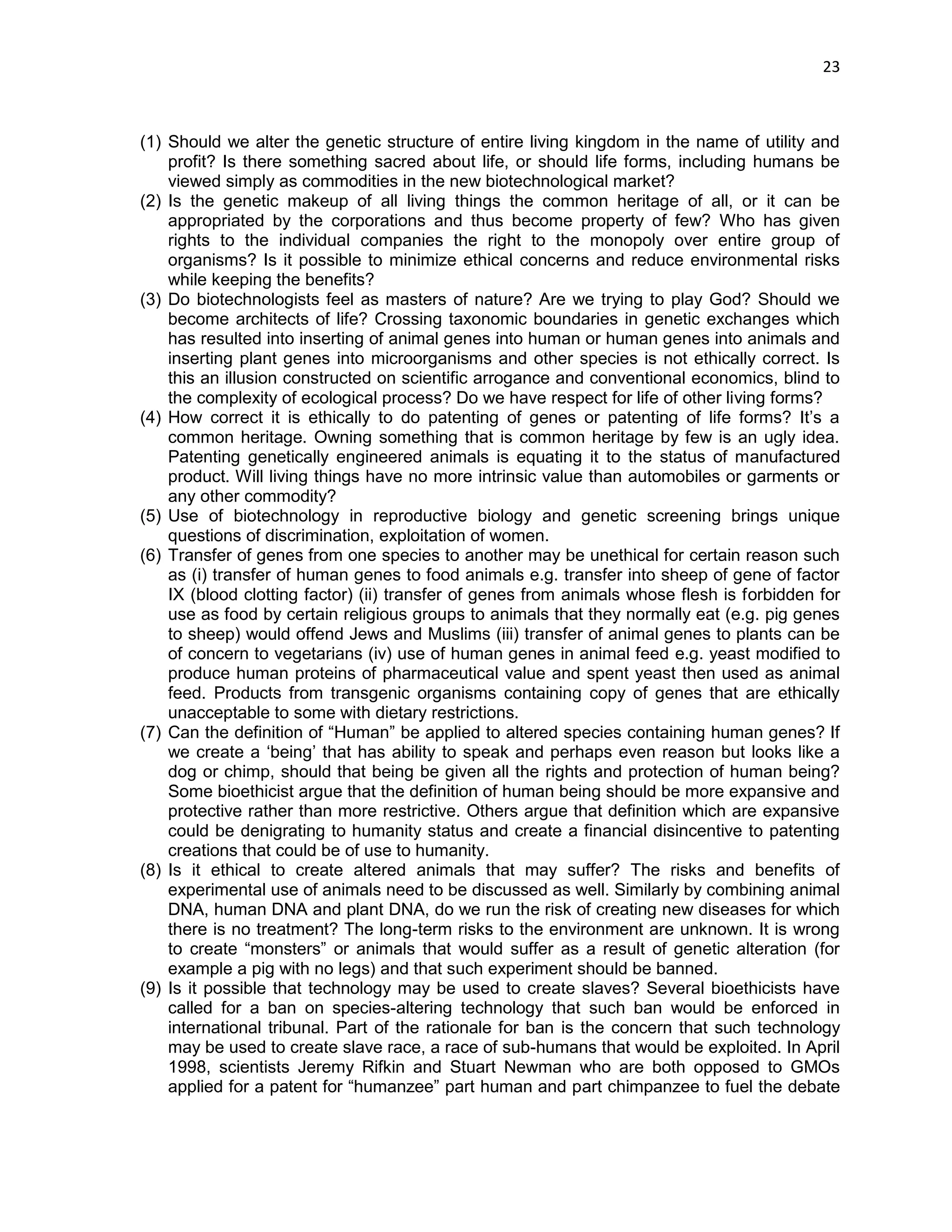

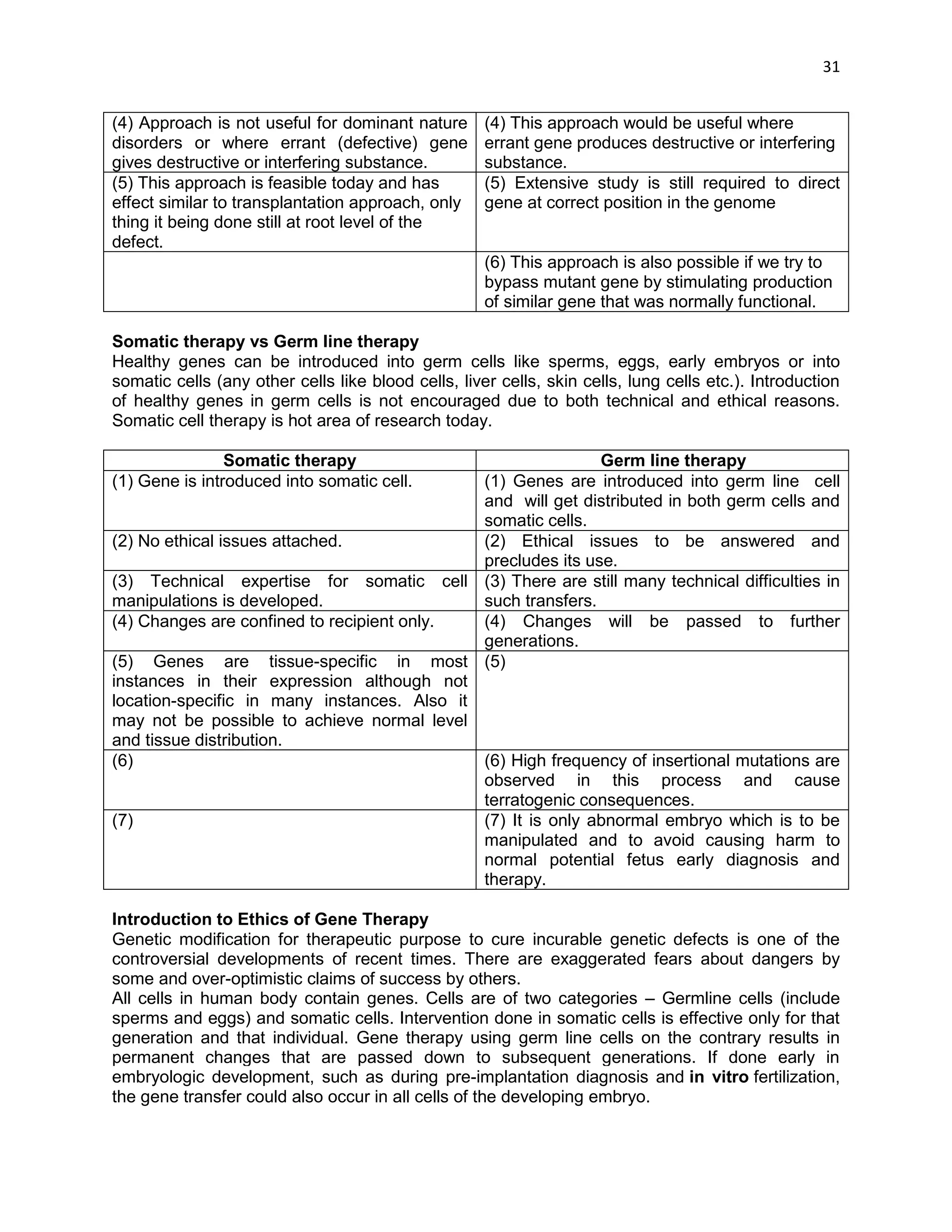

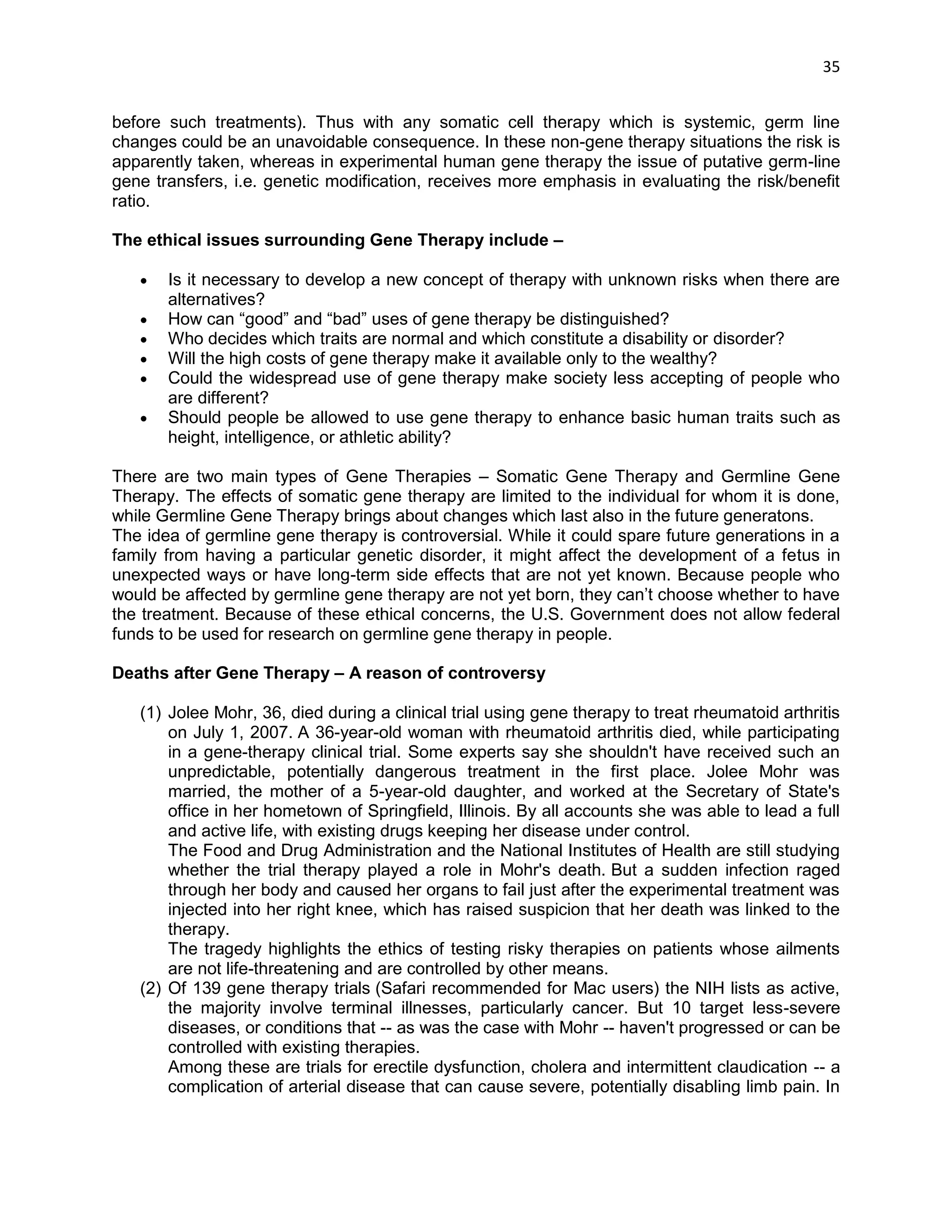

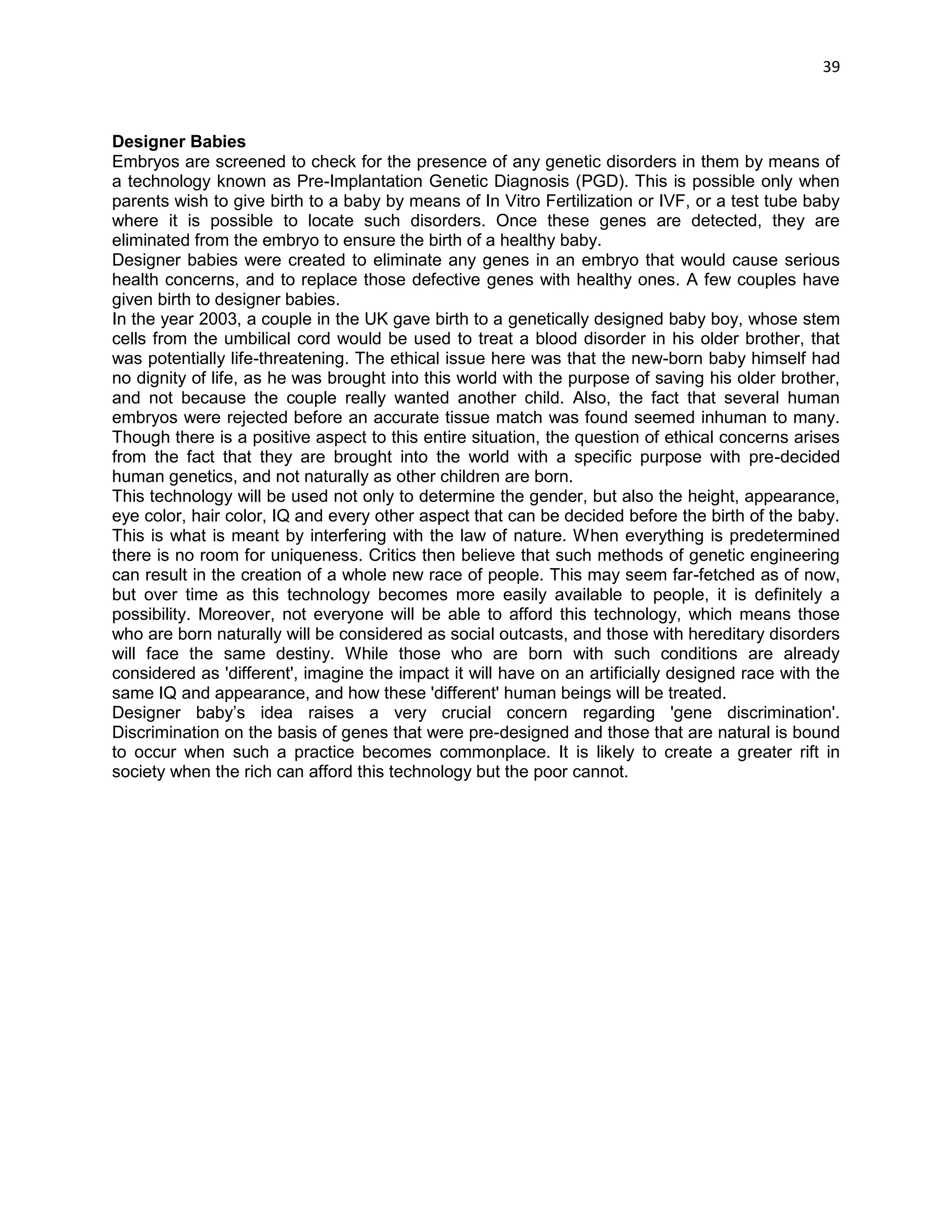

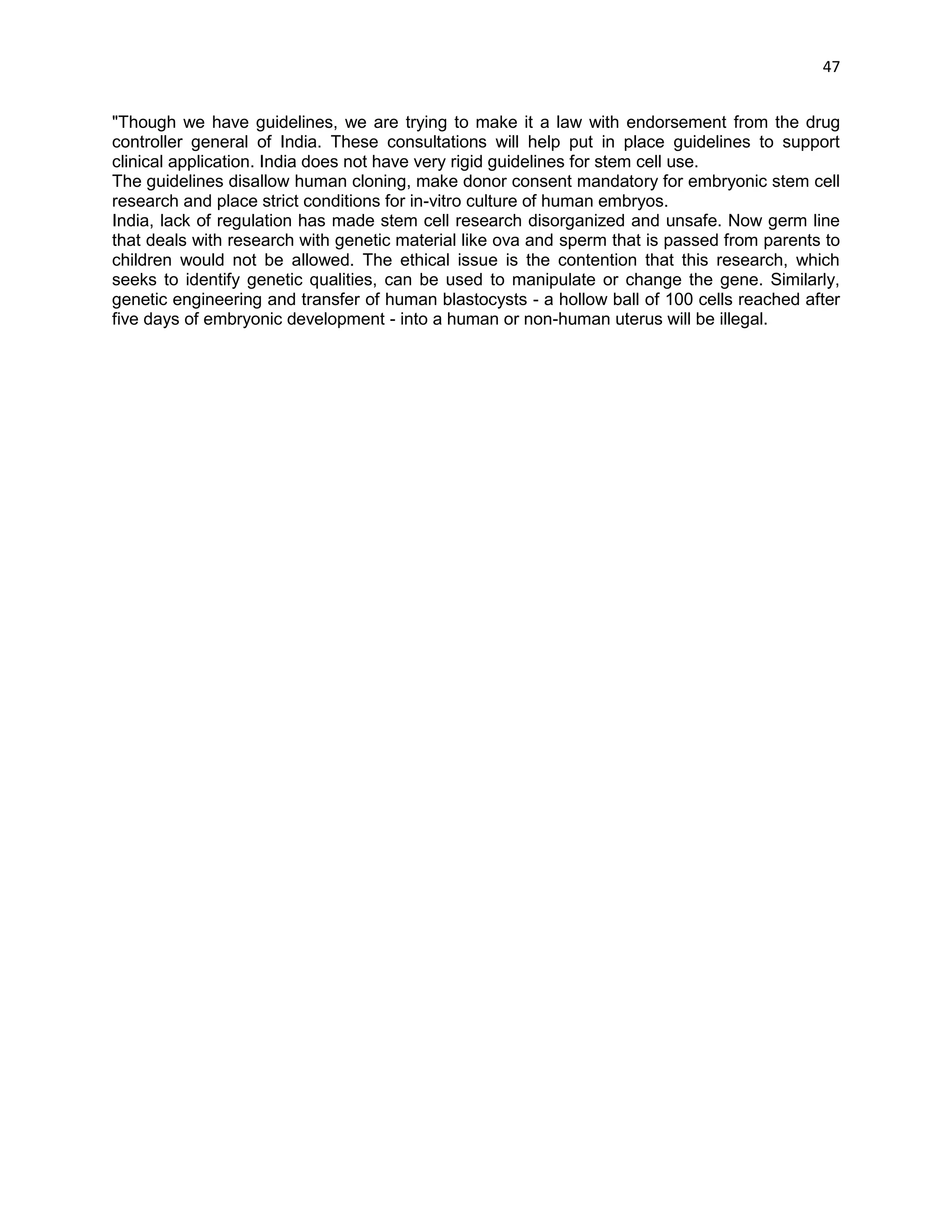

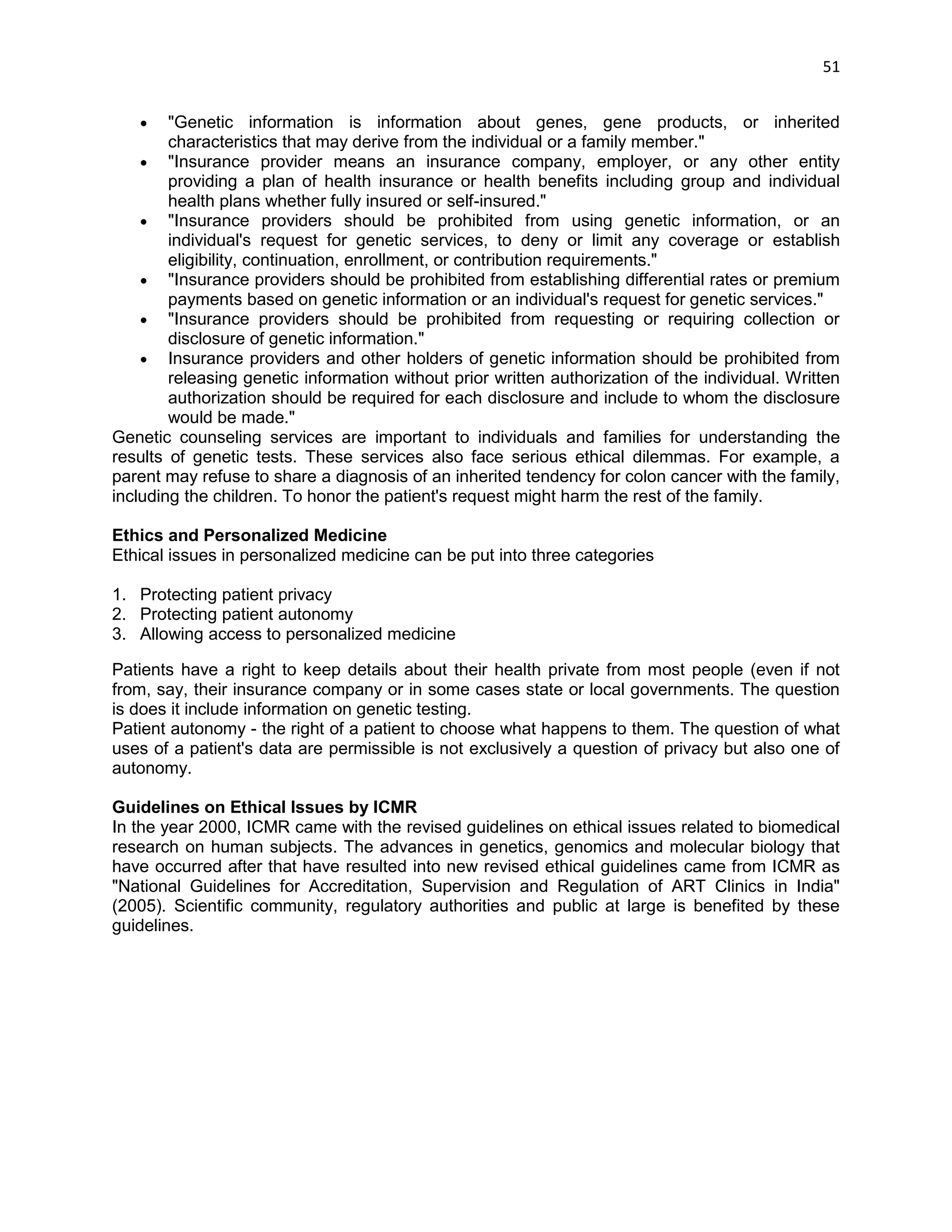

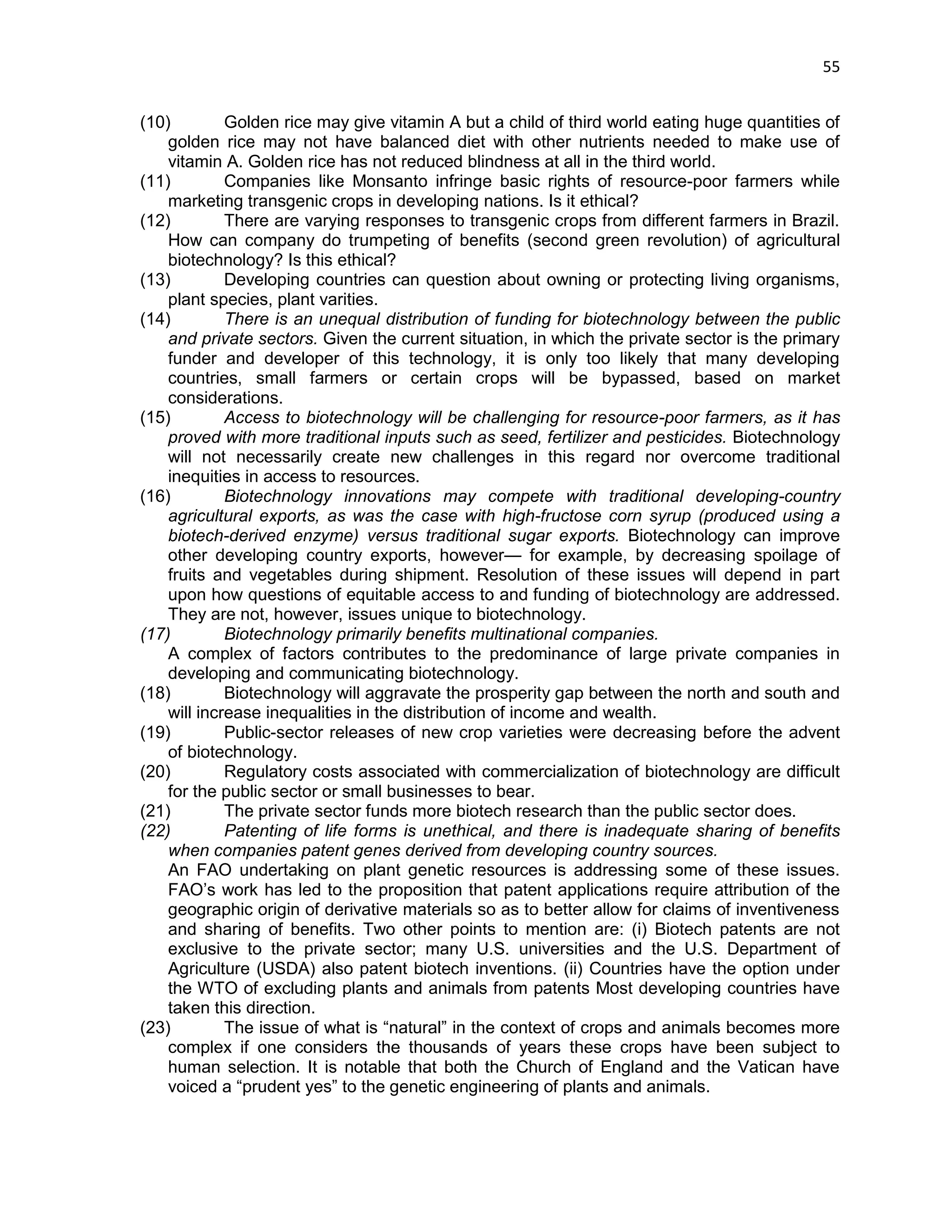

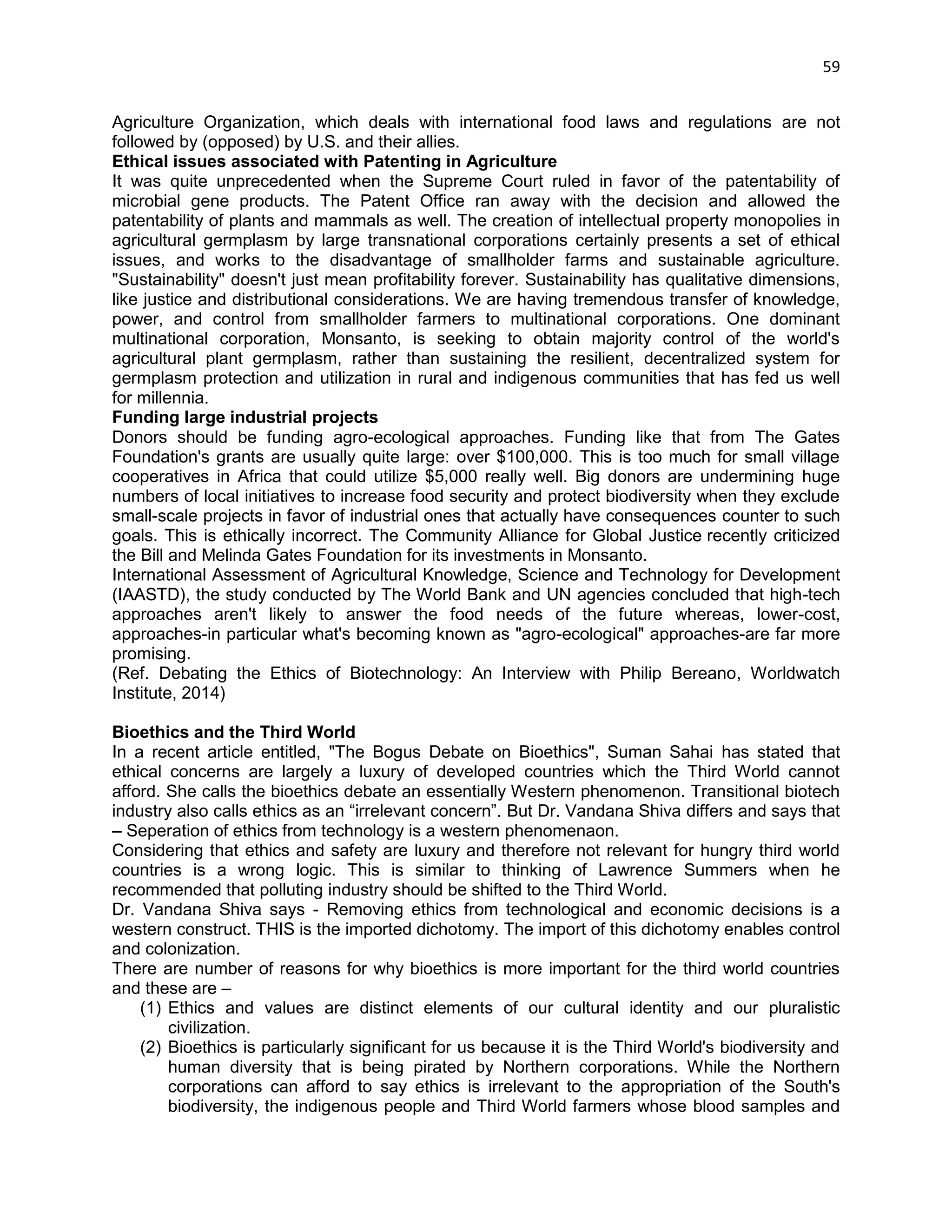

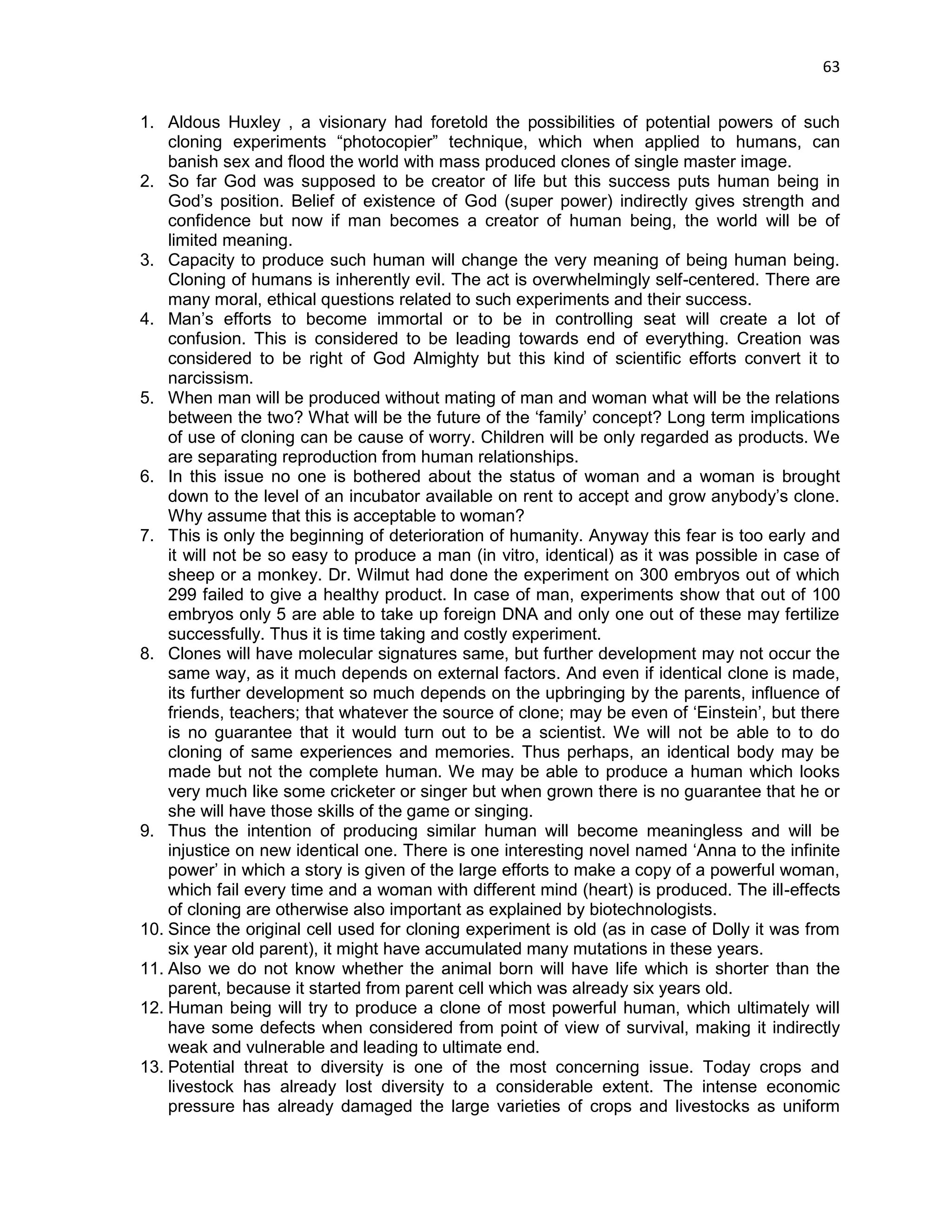

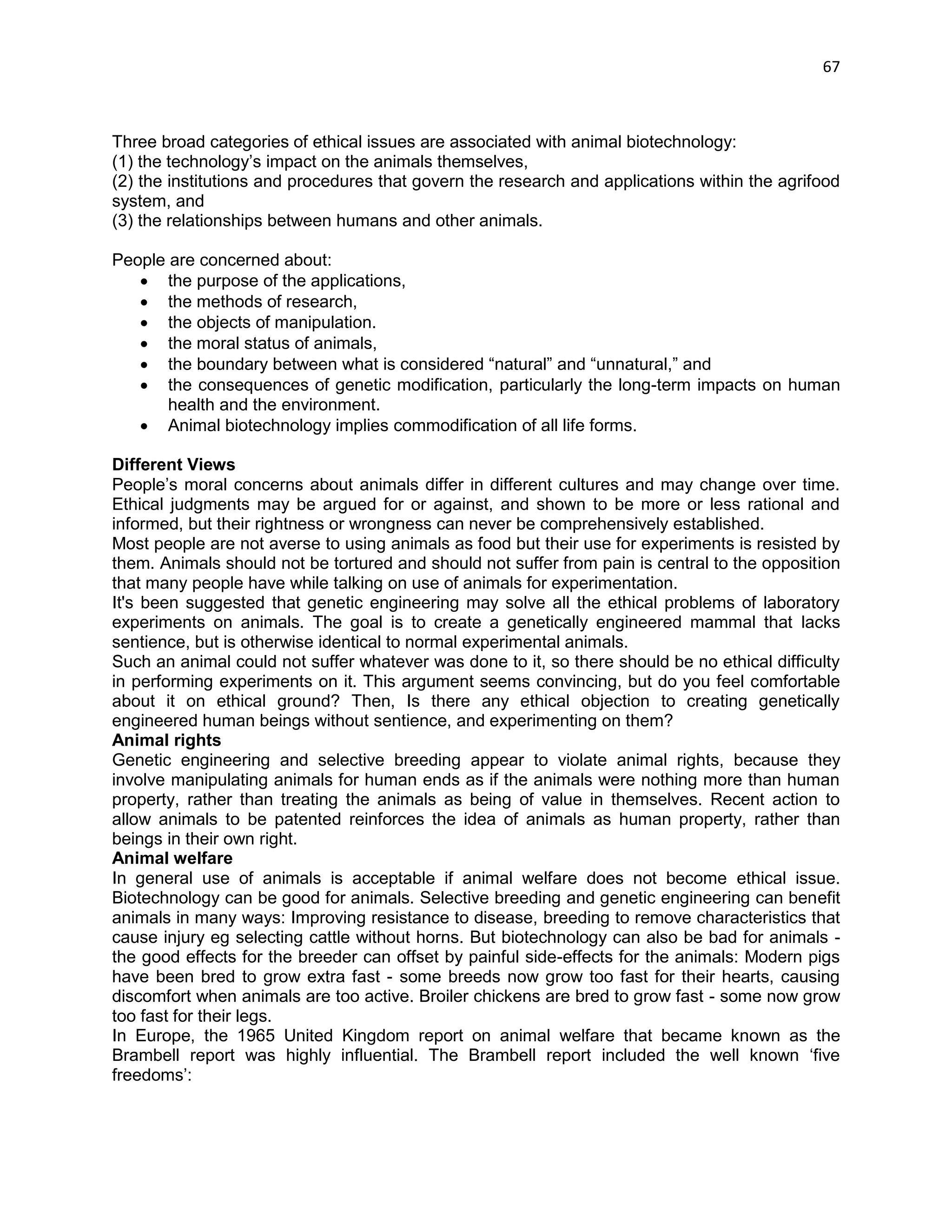

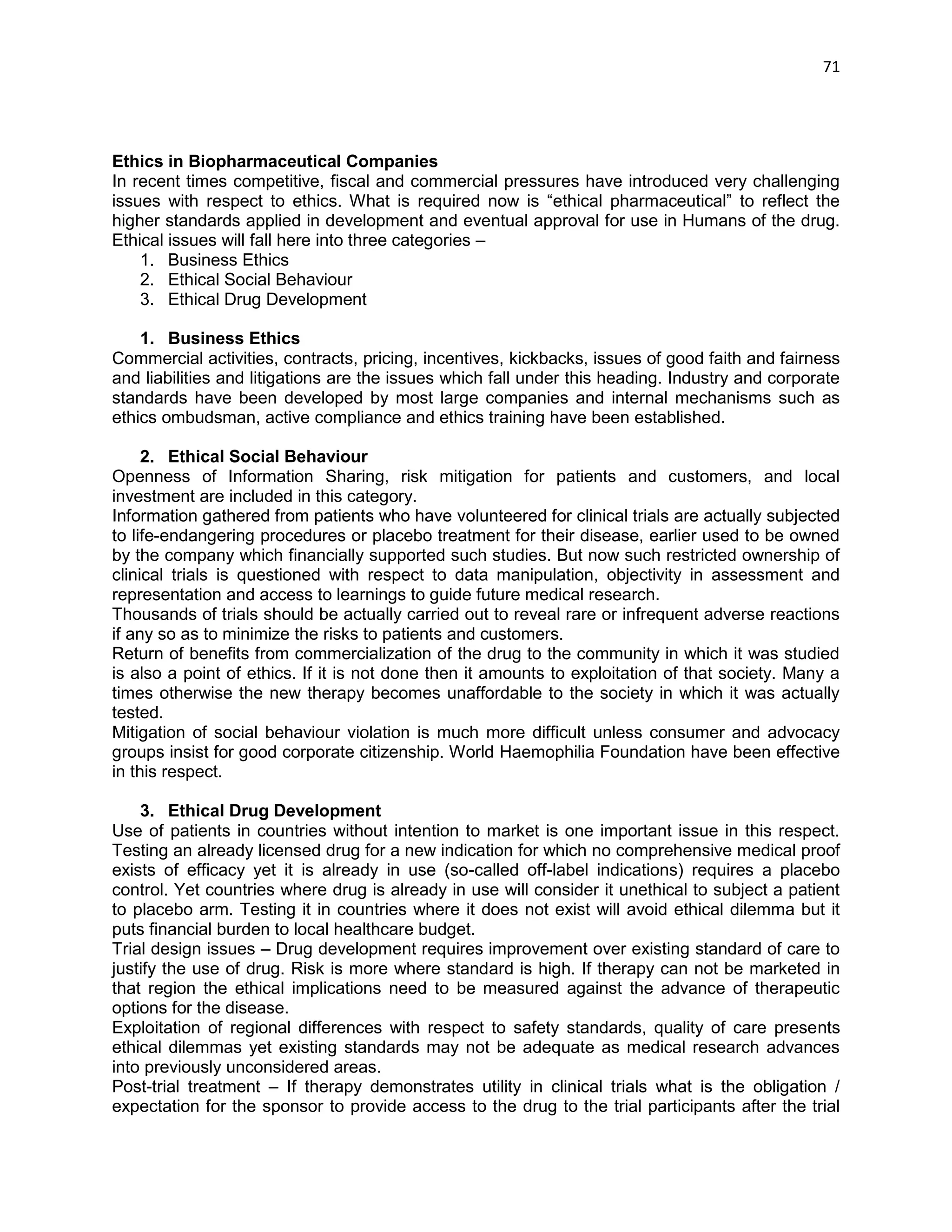

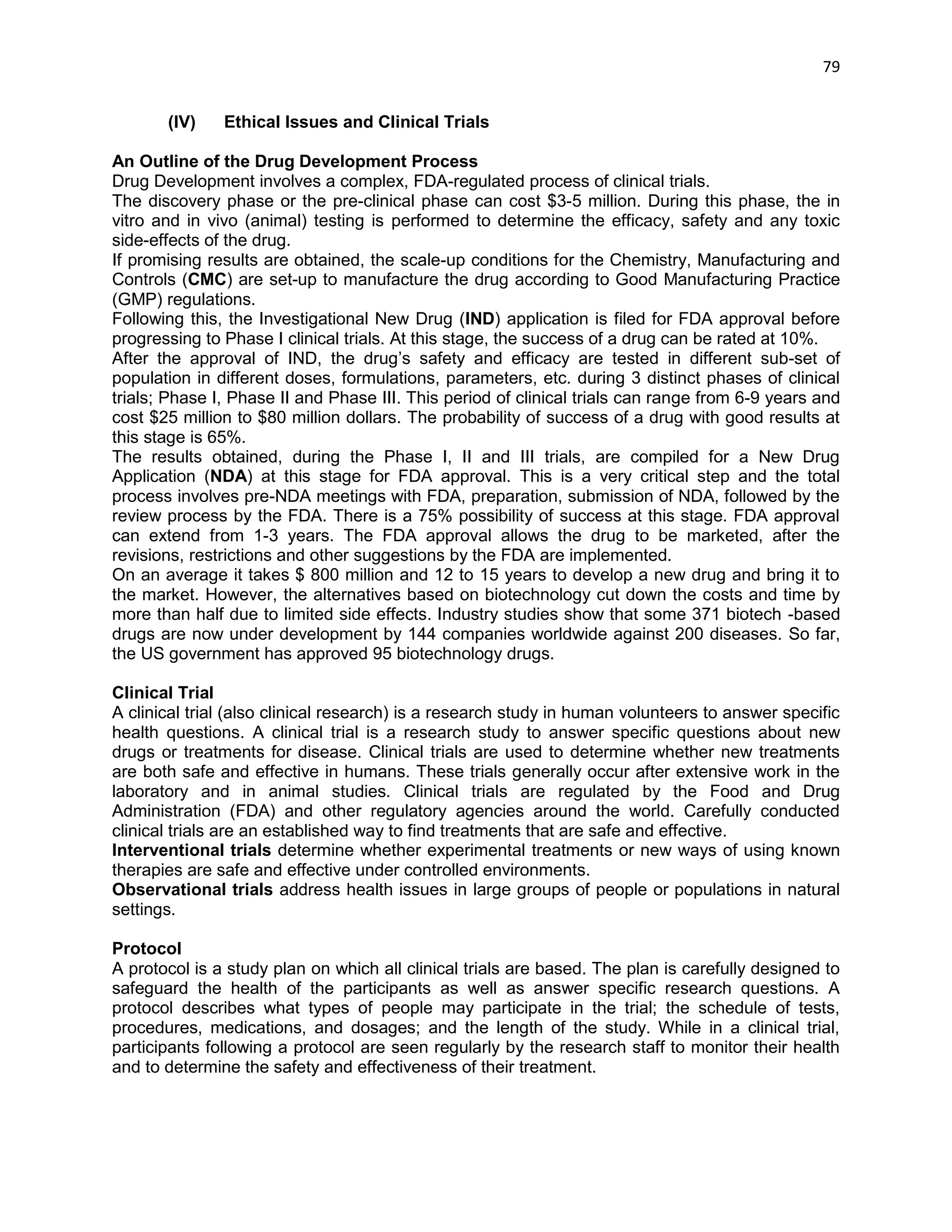

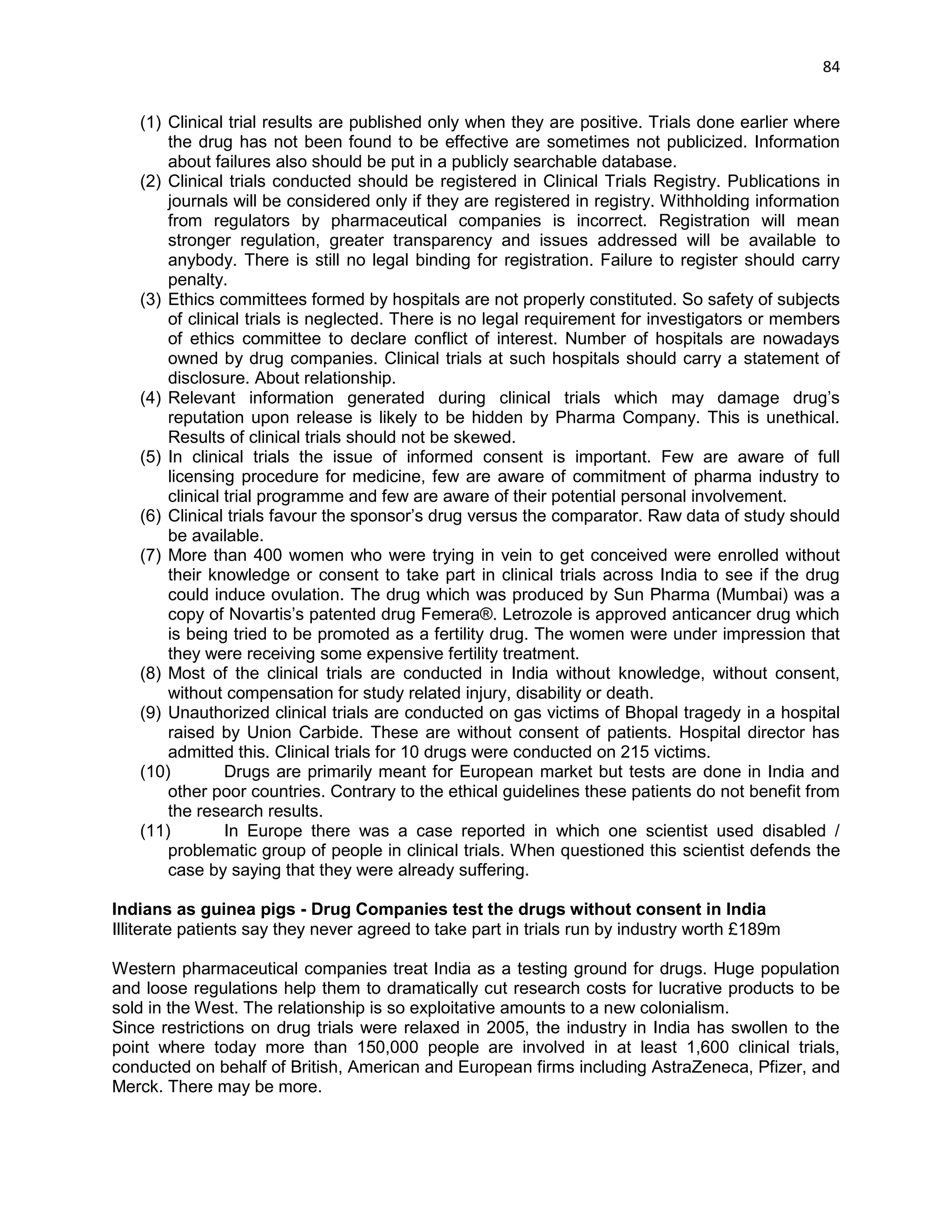

Phase of Clinical trial

Target Group

Period Normally Required

Preclinical Studies

On laboratory animals

6.5 years

Phase I Clinical Trial

20-100 Healthy Human Volunteers

1.5 years

Phase II Clinical Trial

100-500 Patient Human Volunteers

2.0 years

Phase III clinical trial

1000-5000 Patient Human Volunteers

3.5 years

Phase IV Clinical trial

Post Marketing Testing](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/ethicalissuesinbiotechnologyandrelatedareas-141211030119-conversion-gate01/75/Ethical-issues-in-biotechnology-81-2048.jpg)

![87

Indian government officials claim the system includes checks and balances which are being continually improved. According to Dr Vishwa Katoch, director general of the Indian Council of Medical Research, there has been a remarkable improvement in the functioning of the ethics committees. In the last 15 years.

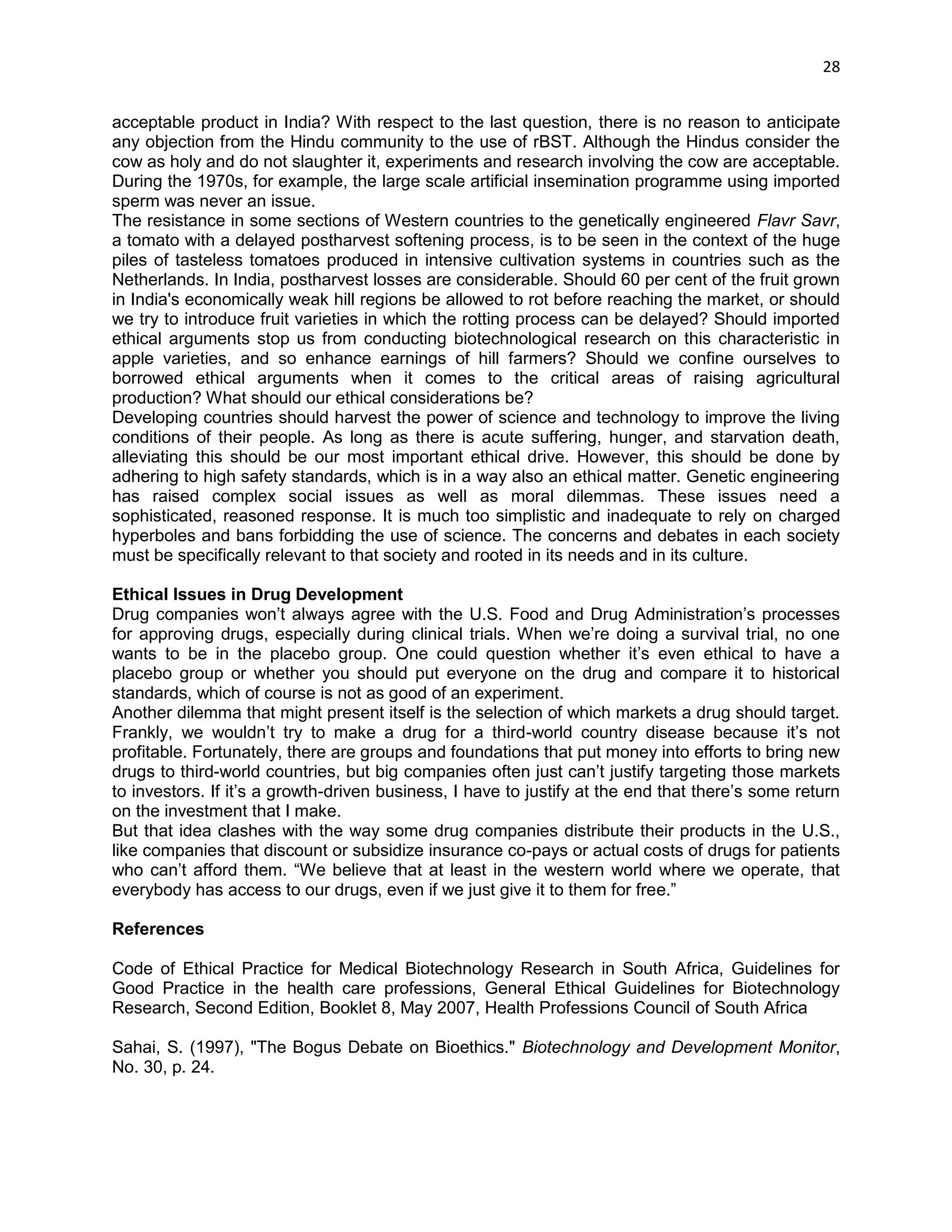

Case study: Sarita Kudumula, 13 - Parents only knew Sarita had been in a study after she died

The teenager (13-year-old Sarita Kudumula) who died had been part of a study carried out in a remote part of the southern Indian state of Andhra Pradesh (AP) to test the feasibility of vaccinating large numbers of young women against the Human Papiloma Virus (HPV), which is sexually transmitted and is one of the causes of cervical cancer. The trial, administered in conjunction with the state government, was led by a US-based NGO, Path, which received millions of dollars from the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation. Samples of an anti-cancer vaccine, Gardasil, produced by US company Merck, were provided free of charge. Officials wished to know whether the vaccine could be introduced as part of a national immunization programme. Up to 74,000 women in India reportedly die from the disease every year.

It seems unlikely that Sarita died as a result of her participation in the study. No one knows exactly what led to her death or those of six others involved in the study in AP and the western state of Gujarat, where another drug, Cervarix, produced by GlaxoSmithKline, was used instead of Gardasil. Both Path and Merck insist that Gardasil is safe. A post-mortem carried out after the girl's death suggested she had committed suicide – a conclusion her parents refuse to accept. A subsequent investigation by the federal government – which suspended the trial after the deaths sparked controversy – concluded it was unlikely the girls had died as a result of having been given the vaccine. The parents of hundreds of other tribal girls, were not informed their daughters were taking part in a trial – something that is in breach of guidelines laid down by the Medical Research Council of India, which demands that those participating in trials give "informed consent".

"Nobody came to ask us for permission," said Sarita's father, a farmer, sitting outside his thatched hut in the village of Anjipakka, as he remembered his daughter, who died in January 2010. "She enjoyed the hostel. She was a bright student and took part in all the social activities. She was intelligent. She wanted to become a doctor."

When The Independent visited the pink-painted Government Girls' Ashram and High School in the nearby town of Bhadrachalam, the hostel warden confirmed that health officials had come to the hostel and outlined their plan to vaccinate 300 girls. He said that because it was a government project, he had been told he could authorize the trials without parental permission. "We did not show any forms or ask for the signatures of the girls or the parents," he said. The warden claimed the vaccination programme went off without a hitch.

While the government inquiry did not link the vaccine to the death of the girls or suggest there had been a "major violation of ethical norms", members of the enquiry panel were concerned that tribal girls had participated in the study without consent. "The most significant deficiency in the implementation of the trial was the obtaining of consent," said one finding.

Officials at Path's India office say the study was carried out after the vaccine was already licensed and was not strictly a clinical trial. "Among over 23,000 girls vaccinated [in AP and Gujarat] through the project, seven girls passed away, but the deaths occurred weeks or months following vaccination," said Tarun Vij, Path's country head. Regarding consent, he said: "The state government authorized the wardens to provide this consent for girls who were living at residential schools."

Spokesmen for the Gates foundation, Merck and GlaxoSmithKline all emphasized that the drugs involved in the studies are safe. A GlaxoSmithKline spokesman added that the trials were carried out according to the same standards wherever they were conducted in the world. On the issue of consent, Gates foundation spokesman Chris William said: "The implementing partner on the ground (the state of AP) made the decision to empower headmasters to provide consent](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/ethicalissuesinbiotechnologyandrelatedareas-141211030119-conversion-gate01/75/Ethical-issues-in-biotechnology-87-2048.jpg)

![90

unusually high. After the inspection, warning letters were sent out to both companies. What action was taken, if any, is unknown.

In another of the three trials, an antibiotic study carried out by Quintiles on behalf of Wyeth, now a part of Pfizer, 32 out of 34 patients were gas victims. Participants in the "Tiger" trial suffered five "serious adverse events" and three deaths. The deaths were classed as "unrelated" to the investigational drug without independent or laboratory tests, and were not eligible for compensation. BMHRC made a profit of 1,936,158 rupees.

Pfizer insists it conducted only two trials there; the hospital says it received money for four. Pfizer said the studies were "conducted by doctors at the hospital" and were carried out "with the informed consent of the study participants and with oversight by the hospital's ethics committee. The standards were no different than for trials conducted in the US, the EU, or elsewhere in the world." Compensation is always approved by principal investigators, ethics committee and regulator.

The Oasis-6 cardiac trial, in which six Bhopal patients died, highlights the problem of assigning responsibility. GSK purchased the test drug, fondaparinux, from the French company Sanofi- Synthelabo (now Sanofi-Aventis), in 2004 when the trial had already started in India. Under its contract, GSK say Sanofi remained responsible for the conduct of the study, while it was responsible for evaluating the data. A CRO was employed in India; the study co-ordinator was in Canada. Sanfoi claims that Sanofi's clinical trials are conducted ethically and are in line with Good Clinical Practice guidelines, and are conducted under the supervision of the institutional ethics committee.

In one trial it was observed that Principal investigator of the trials had his wife on the ethics committee which was clear case of serious conflict of interests.

Patients from a cardiology study known as PLATO, on behalf of AstraZeneca said that they were never told that they had participated in the trial.

Quintiles, the world's biggest CRO, actively recruited patients at BMHRC in four studies and conducted preliminary work in three others. It said in a statement that "clinical staff visited the sites on a regular basis to ensure the studies were conducted as dictated by the protocol and in accordance with international and national ethical guidelines."

References:

Jennifer Miller, Biotech Companies sued for violating patients privacy & other ethics violation, (2008). http://www.businessweek.com/ap/financialnews/D8U2NDU03.htm

Andrew Buncmbe, Nina Lakhani, Without consent: how drugs companies exploit Indian 'guinea pigs', ‗The Independent‘, 14 November 2011.

Nina Lakhani, From tragedy to travesty: Drugs tested on survivors of Bhopal, ‗The Independent‘, 15 November 2011.

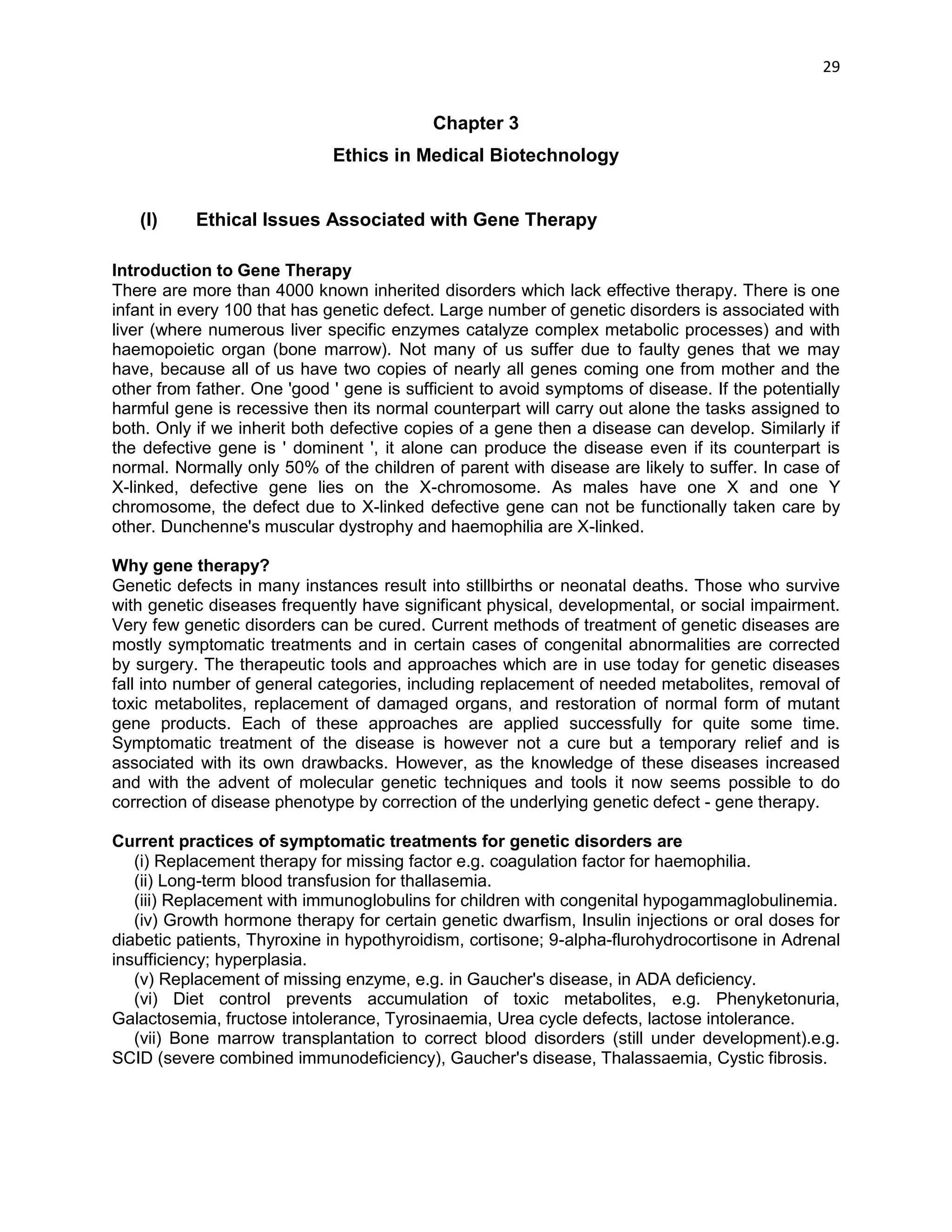

[B] What exactly is the HIV vaccine? [/B]

The preventive vaccine under development is described as a 'modified vaccinia Ankara (MVA) vaccine'. Genetic material from six HIV genes (env, pol, gag, rev, nef and tat) from an Indian isolate of subtype C (accounting for 80 % of infections in India) is inserted in an MVA viral 'vector' -- or transport mechanism for the HIV DNA. Scientists say that vaccinia Ankara is a harmless version of a pox virus; it was also the basis for smallpox vaccines. The vaccine is constructed from pieces of HIV DNA, which cannot form a whole virus, and so there is no risk that recipients of the vaccines could become infected with HIV.

The idea is that when the immune system recognises the HIV genetic material contained in the vaccine, it will stimulate the production of cytotoxic T lymphocytes, specific immune cells that kill](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/ethicalissuesinbiotechnologyandrelatedareas-141211030119-conversion-gate01/75/Ethical-issues-in-biotechnology-90-2048.jpg)

![91

other cells infected with HIV. Thus the preventive vaccine would prepare the immune system to react fast if the person becomes infected with HIV, and control the virus before it is able to take hold. This approach is based partly on research to understand how it is that some people don't get infected with HIV despite repeated exposure to the virus; it was found that they had naturally high levels of these HIV-specific 'killer cells', which presumably enable them to resist infection.

Trials of HIV vaccines are being carried out world-wide, though it will be many years before a vaccine will reach the market. IAVI-sponsored research has produced two candidate vaccines currently under trial in Africa. Glaxo Smith Kline has a protein-based vaccine poised to enter trials. The Phase III trial by the Bangkok Vaccine Evaluation Group of VaxGen's gp120 vaccine, in a cohort of 2545 intravenous drug users, is ongoing.

Some activist groups have given a cautious welcome to the announcement of an HIV vaccine for India. They raise three basic questions: 1) Will all efficacy be maximised and risks minimised? 2) Will the programme move carefully to ensure that vulnerable groups are not exploited, and that human studies are appropriate, done with fully informed and voluntary consent of participants, and do not harm them physically or socially? 3) How will vaccine research and development proceed effectively when preventive programmes are in chaos, and drug treatment is a luxury for the very, very rich?

Partners of commercial sex workers and intravenous drug users - people at high risk of getting infected with HIV -- have been identified for the vaccine trials in Maharashtra, Tamil Nadu and the North-East.

IAVI is a non-profit organisation founded in 1996 to help develop preventive HIV vaccines for use throughout the world. According to its website (www.iavi.org), its work is concentrated in four areas: "creating global demand for AIDS vaccines through advocacy and education; accelerating scientific progress; encouraging industrial involvement in AIDS vaccine development; and assuring global access". IAVI's funders include USAID, the World Bank, UNAIDS and various private foundations.

Boston, USA-based Therion Biologics Corporation is essentially in the development of therapeutic vaccines for cancer, according to Mark Chataway of IAVI. According to Therion's website, it is also developing preventive AIDS vaccines in a programme supported entirely by the United States National Institutes of Health. It has four such candidate vaccines in development, one of which is in Phase I clinical trials.

IAVI and the Indian government have committed themselves to ensuring that AIDS vaccine clinical trials in India will be conduced with community participation and adequate infrastructure, and after addressing the ethical issues concerning clinical trials. The government says the process will be transparent and it will ensure that participants' consent is voluntary and informed. It says that meetings planned with the various stakeholders are meant to solicit their support to expedite vaccine research.

The April 16 announcement raises a number of issues that merit informed public discussion. A few of them are mentioned below:

[B]AIDS vaccine trials pose a number of ethical problems, particularly in countries like India [/B]where a higher estimated incidence of HIV (than for example in the US) permits smaller sample sizes and faster results. They are conducted on groups whose vulnerability is the very reason they are at higher risk of HIV.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/ethicalissuesinbiotechnologyandrelatedareas-141211030119-conversion-gate01/75/Ethical-issues-in-biotechnology-91-2048.jpg)

![92

[B]These trials depend on healthy participants getting exposed to the virus due to their behaviour[/B]; a significantly higher incidence of HIV in the control group is needed to prove the vaccine's efficacy. Researchers experience a conflict of interests: between this technical requirement and their obligation to provide preventive advice on safer sex and injecting practices, as well as condoms and clean needles or bleach.

[B]Researchers will also have to ensure that participants truly understand that the experimental vaccine is not proven effective[/B], and they should presume that it offers no protection. Further, participants will not know if they have received the experimental vaccine or a placebo which offers no protection at all.

[B]What will the standard of care be for participants who become sero-positive during the AIDS vaccine trial?[/B] The Helsinki Declaration requires that participants in a trial be provided the best known prophylactic and therapeutic care. Will the government commit to providing the highest possible standard of treatment - life-long triple anti-retroviral therapy -- as available to research participants in the developed world?

[B]None of the vaccines under development are expected to have 100 per cent efficacy[/B]. In fact, a vaccine of just 50 per cent efficacy may be considered acceptable for a country with a high prevalence of HIV, because of the number of infections it could reduce. Before trials begin, we will need to know more about the estimated efficacy of the vaccine currently poised for trials in India. Second, given the controversies on HIV figures in India, we will need to know by what calculation it was considered acceptable. Finally, how will the programme ensure that vaccinated people truly understand the limits of protection?

[B]Ensuring availability:[/B] The NACO-ICMR-IAVI venture envisages that once a vaccine is developed and clears Phase I clinical trials, Therion would transfer the technology to an Indian pharmaceutical for further production and trials. The licensed vaccine would be sold in this region at 'manufacturing cost (excluding all development costs) plus a small margin'. This may still be unaffordable to the majority of people at risk of HIV. The programme needs to tell us exactly how it will make any AIDS vaccine available to the poorest of the poor, who would need it the most.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/ethicalissuesinbiotechnologyandrelatedareas-141211030119-conversion-gate01/75/Ethical-issues-in-biotechnology-92-2048.jpg)

![94

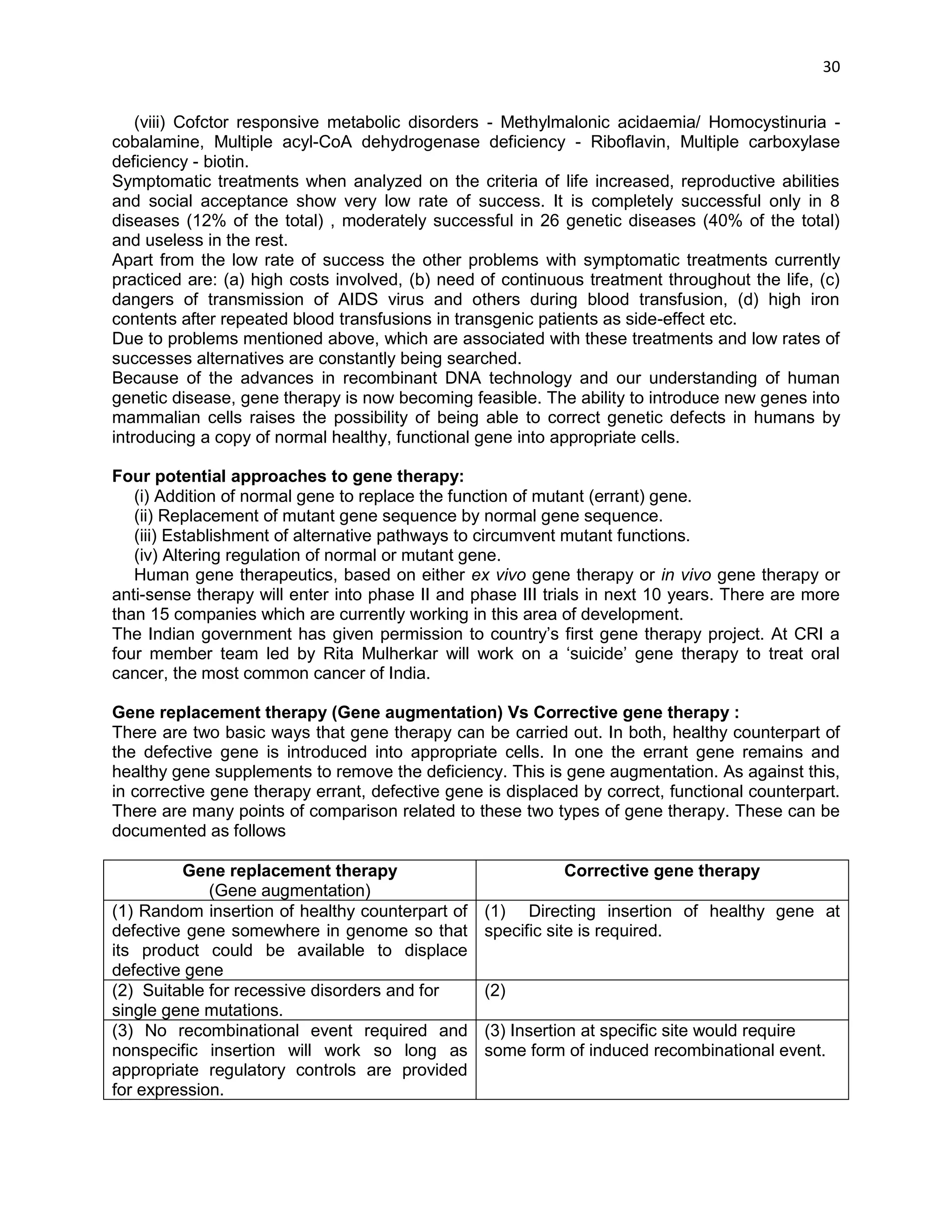

The first reports on synthetic biology raise the question whether synthetic biology opens up radically new ways of fabricating life, and as a side-effect will change how we conceive of ourselves:

The production and/or modification of simple living organisms and their potential use to fabricate more complex ones raises the questions as to how far we want to assign a mere instrumental value of such organisms and our relation to the biosphere itself. In this regard, the ethics of synthetic biology, addressed within the framework of ecological ethics, raises questions of uncertainty, potentiality, and complexity. There are many different approaches to environmental ethics, mostly grouped as ‗anthropocentric‘, ‗biocentric‘, and ‗ecocentric‘. The EGE described the ethical debate on eco-centric theories in its Opinion on Modern developments in agriculture technology. It is important to underline that such theories have advocated the intrinsic value of the biosphere or the ethical dimension of nature.

Eco-centric environmental ethics questions the traditional ethics of rights and obligations, and asks instead in what kind of world we may wish to live in. Taken as such, ecological ethics advocates the change of traditional, if not modern values and goals at individual, national and global levels, and integrate the protection of the environment in a new view towards human beings, life, and nature.

Eco-centric theories apply to the use of synthetic biology to manufacture or modify life forms, as well as ecological considerations for synthetic biology in environmental protection. The relevance of such arguments should be considered in relation to uses of synthetic biology, although some theories of eco-centric ethics may intrinsically oppose synthetic biology when interacting with existing life forms or when (in a futuristic and hypothetical sense) synthesising complex organisms.

Anthropocentric theories, on the contrary, justify making instrumental use of nature for human purposes, although it is underlined that there are limits to human activities affecting the environment because they may damage the well-being of human beings now and in the future, since our well-being is essentially dependent on a sustainable environment. Anthropocentric ethics argues strongly that humans ought to be at the centre of our attention and that it is right for them to be so. Anthropocentric approaches to synthetic biology focus much more on consequential considerations and issues related to potential consequences from the use of synthetic biology for human beings (risk assessment and management and hazard considerations). Where do we draw the line between what is certain, what could be certain and what remains, at least for the time being, uncertain?

Specific ethical issues raised by synthetic biology concern its potential applications in the fields of biomedicine, biopharmaceuticals, chemicals, environment and energy and the production of smart materials and biomaterials.

Risk versus Benefits

While thinking about ethical issues it is the risk-benefit analysis that is important. Likely benefits that we know now range from better production of vaccines to environmentally friendly biofuels to developing, in the near term, semi-synthetic anti malarial drugs. And these benefits are substantial. The risks are all prospective; they're not current, because the field is still in its infancy. But probably the primary risk that needs to be overseen is introducing novel organisms into the environment, [and] how they will interact with the environment.

"Do-it-yourselfers"

The "do-it-yourselfers" are individuals who work not in institutional settings. Do-it-yourself biology is an important and exciting part of this field and it showcases how science can engage people across our societies who don‘t have university or industrial affiliations. At the same time,](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/ethicalissuesinbiotechnologyandrelatedareas-141211030119-conversion-gate01/75/Ethical-issues-in-biotechnology-94-2048.jpg)