The document discusses several key issues in media law and ethics including:

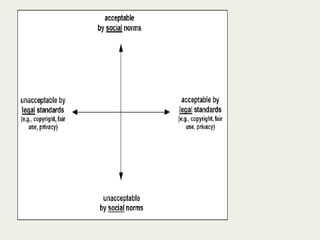

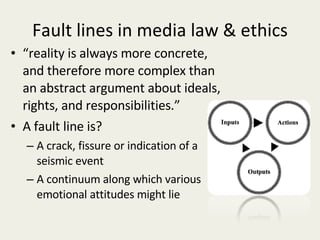

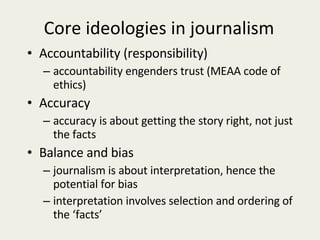

1. The relationship between legal and ethical issues in journalism and how they are often difficult to separate.

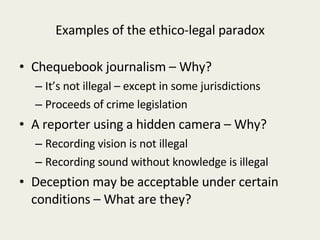

2. Examples of ethical dilemmas journalists may face such as chequebook journalism and using hidden cameras.

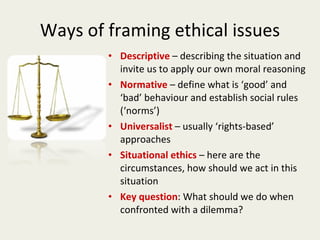

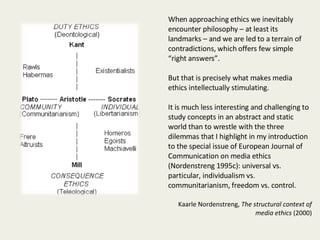

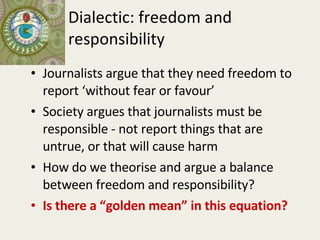

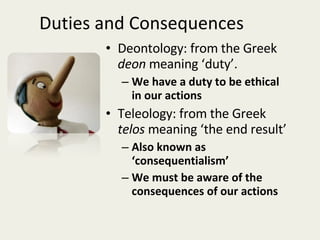

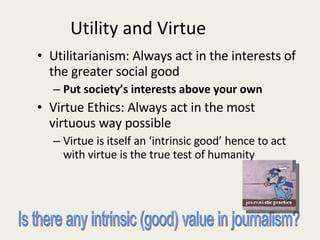

3. Different approaches to framing ethical issues such as descriptive, normative, universalist, and situational ethics frameworks.

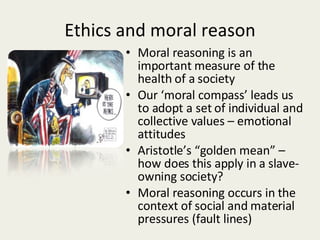

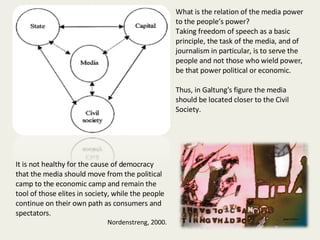

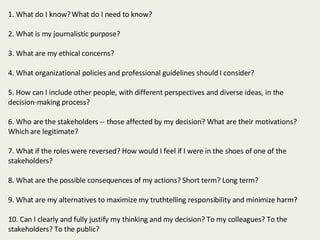

4. The importance of moral reasoning in journalism and how it is shaped by social and material pressures.