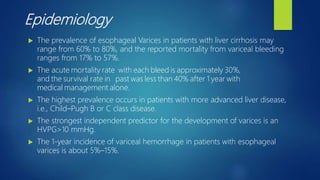

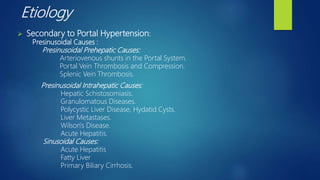

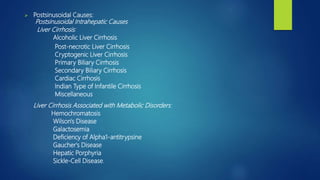

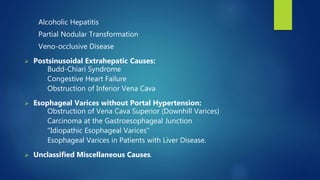

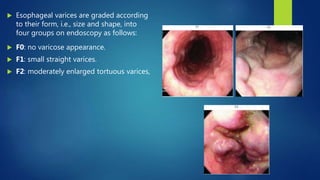

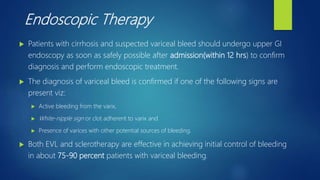

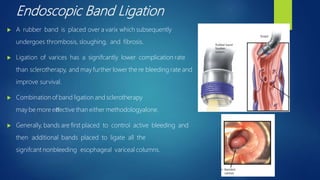

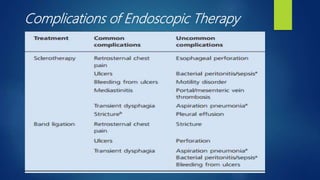

Esophageal varices, caused by increased venous pressure related to portal hypertension, present a serious risk of hemorrhage, particularly in patients with liver cirrhosis. Diagnosis typically involves endoscopic evaluation, while management includes pharmacological intervention, endoscopic therapy, and potentially surgical options, especially in acute cases. Secondary prophylaxis is crucial for patients who have experienced variceal bleeding to prevent recurrence.