The document discusses the challenges and obstacles to reforming the criminal justice system in America, focusing on both ideological and financial barriers. It highlights the influence of the crime control industrial complex and the profitability of crime, exacerbated by global criminal industries, as significant impediments to change. The text also reflects on societal attitudes toward crime, emphasizing the need for evidence-driven policies and interdisciplinary approaches to effectively address crime control and its underlying social issues.

![He expressed concern

that America had created a massive, expensive, and influential

military machine that had

the potential to artificially encourage the country to go to war,

in part to justify its own

existence; that military elites have the power to potentially

influence the country to use its

military might in part because of the economic necessity created

by the military industrial

complex. Criminologists have built upon Eisenhower’s rich

military industrial complex

concept by applying it to a series of criminal justice issues.

Journalist Eric Schlosser (1998) applied Eisenhower’s military-

industrial complex concept

to the economics of prisons. Schlosser defined the prison

industrial complex as “a set

of bureaucratic, political, and economic interests that encourage

increased spending on

imprisonment, regardless of the actual need” (Schlosser, 1998,

p. 1). Similarly, this concept

can be applied more broadly to crime control in general. Thus,

we can define the crime

control industrial complex as “a set of bureaucratic, political,

and economic interests that

encourage increased spending on [crime control] regardless of

the actual need” (Schlosser,

1998, p. 1).

Any systemic reforms to the criminal justice system must

overcome possible resistance

from the crime control and prison industrial complexes. Thus,

as suggested by Karl Marx,

economic dynamics are likely central to the future of criminal

justice policy in America.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/eriks-221030165405-61f7a461/85/Erik-S-LesserStringerGe-docx-6-320.jpg)

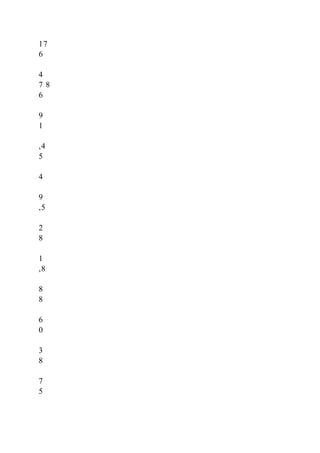

![mirror than by the reality reflected. (Reiman, 2007, p. 62)

Reiman contends that the criminal justice system and the media

present an image of the

“typical criminal” who is “a he . . . young . . . predominately

urban . . . disproportionately

black . . . [and] poor” (Reiman, 2007, p. 63). This image of the

typical criminal discour-

ages a critical examination of the role of social class in the

criminal justice system. It dis-

courages a vigorous study of the harms of white-collar crime.

Debunking these popular

misconceptions about crime and criminal justice is essential to

creating fair and effective

criminal justice policy.

10.3 Crime Reduction: According to the Evidence

One of the reoccurring themes throughout this textbook has

been the social condi-tions that influence criminality. When

society considers how to reduce crime, social structural factors

play a central role. Thus, many criminologists advocate address-

ing larger social structural issues in American society as a

method to reduce crime and

its attendant harms. Society’s response to crime is just that—a

response. An alternative is

coL82305_10_c10_307-338.indd 319 7/5/13 4:23 PM

Section 10.3 Crime Reduction: According to the Evidence

CHAPTER 10

proactive interventions, those that are put into place to prevent

rather than react to prob-](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/eriks-221030165405-61f7a461/85/Erik-S-LesserStringerGe-docx-31-320.jpg)