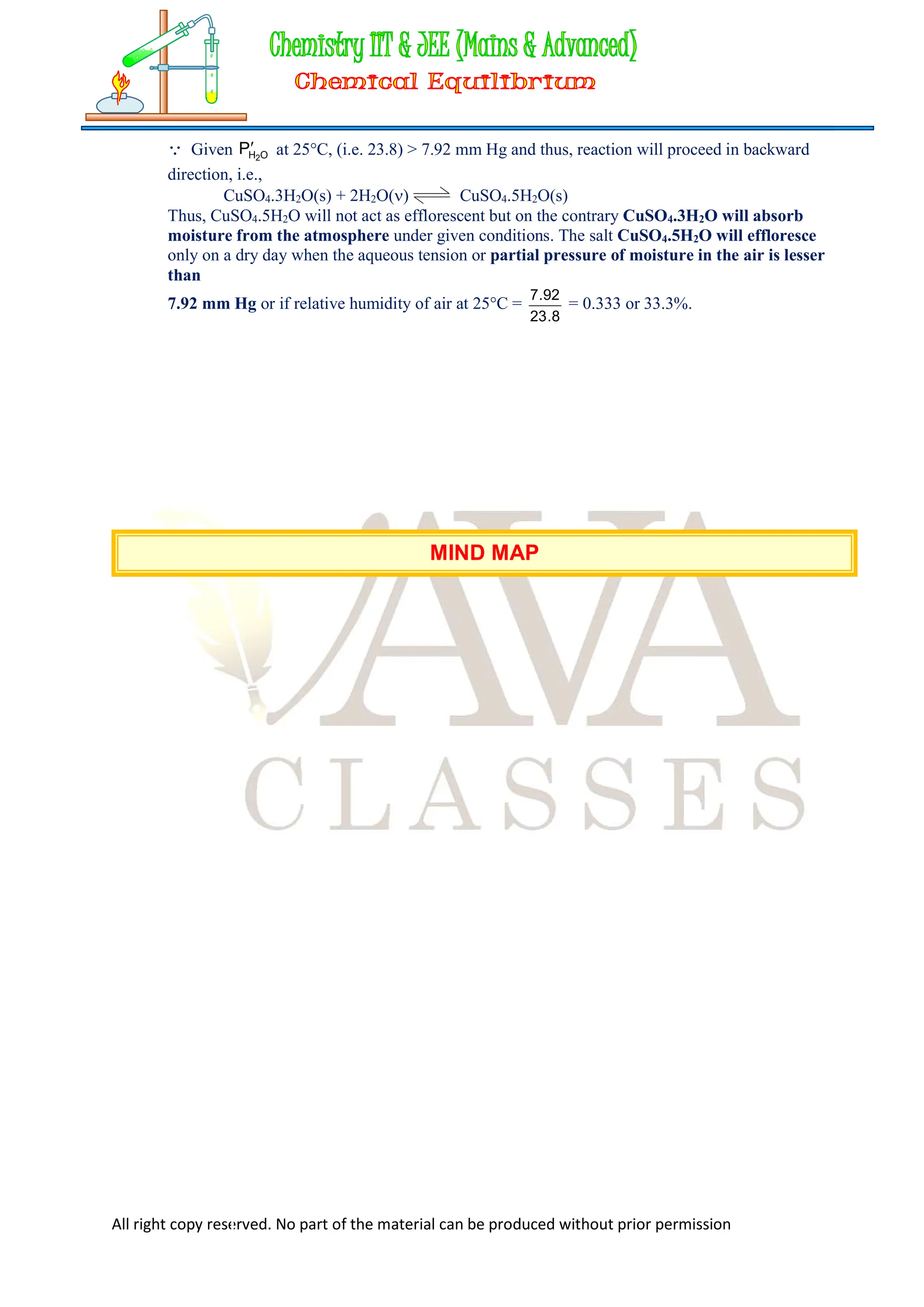

The document discusses the concept of equilibrium in physical and chemical contexts, defining stable and unstable equilibrium and explaining dynamic equilibrium in reversible chemical reactions. It also covers the characteristics of chemical equilibrium, the law of mass action, and the relationships between equilibrium constants for various types of reactions, including how changes in conditions affect equilibrium states. It highlights the importance of understanding reactants and products, as well as the distinctions between homogeneous and heterogeneous equilibria.

![[Type here]

All right copy reserved. No part of the material can be produced without prior permission

Key Features

All-in one Study Material (for Boards/IIT/Medical/Olympiads)

Multiple Choice Solved Questions for Boards & Entrance Examinations

Concise, conceptual & trick – based theory

Magic trick cards for quick revision & understanding

NCERT & Advanced Level Solved Examples](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/chemicalequilibrium-240508121455-3fc1524e/75/Equilibrium-in-Physical-Processes-Class-11-Free-Study-Material-PDF-1-2048.jpg)

![All right copy reserved. No part of the material can be produced without prior permission

80% of the mixture would be converted to HI. If HI is heated at 440C, only 20% would be

converted into H2 and I2. This is an unfailing criterion of a chemical equilibrium.

If one of the conditions (temperature, pressure or concentration) under which an equilibrium

exists is altered, the equilibrium shifts and a new state of equilibrium is reached.

A catalyst does not alter the position of equilibrium. It accelerates both the forward and

reverse reactions to the same extent and so the same state of equilibrium is reached but

quickly. So a catalyst hastens the attainment of equilibrium.

If the reactants and the products in a system are in the same phase, the equilibrium is said to be

homogeneous.

For example,

H2(g) + I2(g) 2HI(g)

represents a homogeneous equilibrium in gaseous phase and

CH3CO2H(l) + C2H5OH(l) CH3CO2C2H5(l) + H2O(l)

represents a homogeneous equilibrium in solution phase.

A phase is a homogeneous (same composition and properties throughout) part of a system,

separated from other phases (or homogeneous parts) by bounding surfaces.

Any number of gases constitute only one phase.

In liquid systems, the number of phases = number of layers in the system. Completely miscible

liquids such as ethanol and water constitute a single phase. On the other hand, benzene - water

system has 2 layers and so two phases.

Each solid constitutes a separate phase, except in the case of solid solutions. [A solid solution, e.g.,

lead and silver, forms a homogeneous mixture.]

If more than one phase is present in a chemical equilibrium, it is said to be heterogeneous

equilibrium.

For example,

CaCO3(s) CaO(s) + CO2(g)

represents a heterogeneous equilibrium involving two solid phases and a gaseous phase.

The law of mass action (given by Guldberg and Waage) states that the rate of a chemical

reaction is proportional to the product of effective concentrations (active masses) of the reacting species,

each raised to a power that is equal to the corresponding stoichiometric number of the substance

appearing in the chemical reaction.

By the rate of a chemical reaction we mean the amount of reactant transformed into products in

unit time. It is represented by dx/dt.

Active mass means the molar concentration, i.e., the number of moles in

1 litre. Suppose 3 moles of nitrogen are present in a 4 litre vessel, the active mass of nitrogen

= 3/4 = 0.75 mole/litre. Active mass of a substance is represented by writing molar concentration in square

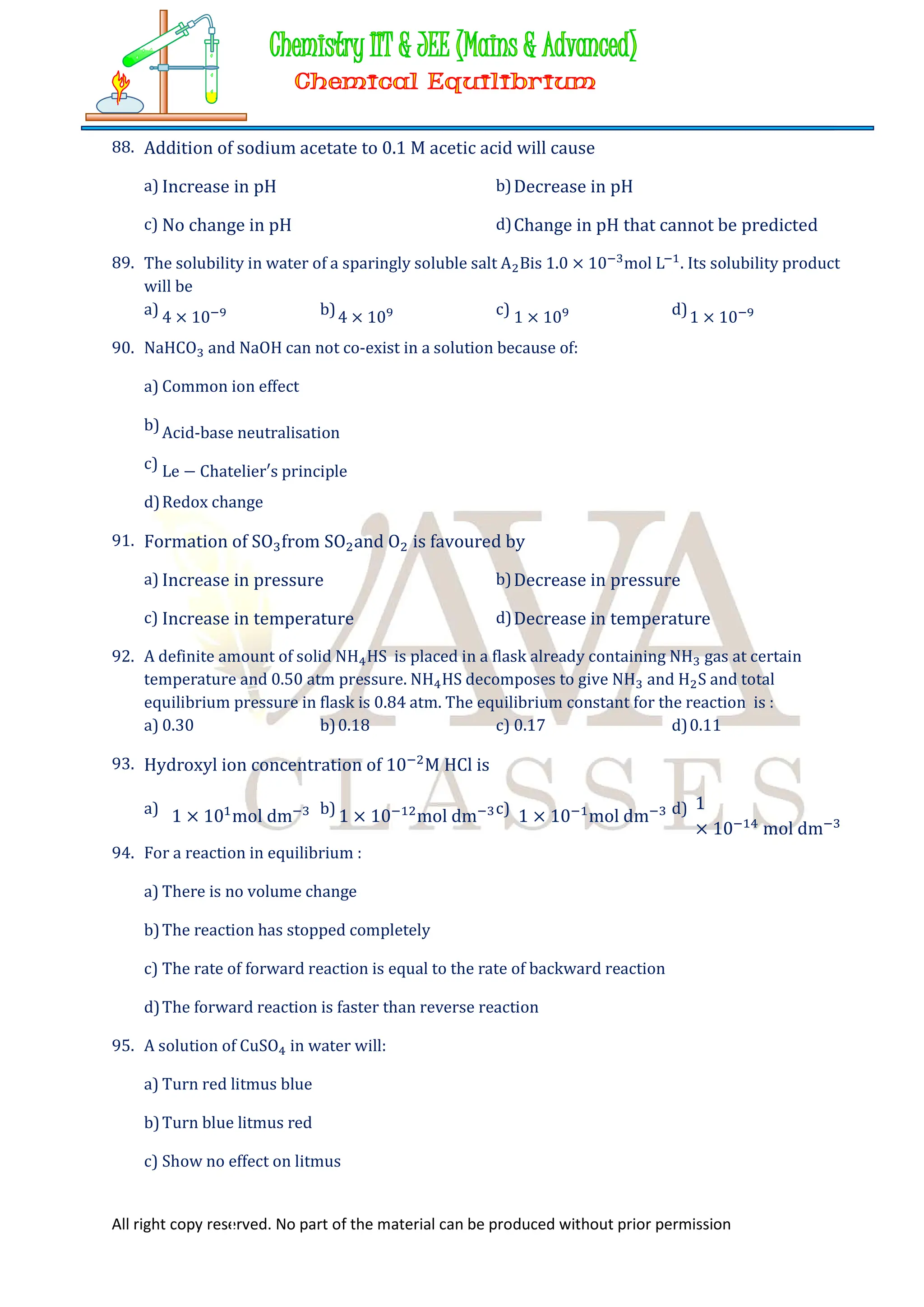

brackets.

Active mass of reactant molarity

Active mass of reactant = molarity

where is the activity coefficient.

a = molarity

THE LAW OF MASS ACTION

3](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/chemicalequilibrium-240508121455-3fc1524e/75/Equilibrium-in-Physical-Processes-Class-11-Free-Study-Material-PDF-4-2048.jpg)

![All right copy reserved. No part of the material can be produced without prior permission

For very dilute solutions, the value of activity coefficient is unity.

activity(a) = molarity.

Thus, in place of activity of any reactive species, molarity can be used for dilute solutions.

In IITJEE Syllabus, only dilute solutions are there, so everywhere we would be using the term molarity in

place of active mass of a species.

(i) Let us have an equilibrium reaction as

X(g) + Y(g) Z(g)

For this reaction, which is in equilibrium, there exist an equilibrium constant (Keq)

represented as

]

Y

[

]

X

[

]

Z

[

K eq

For the given equilibrium, irrespective of the reacting species (i.e, either X + Y or Z or X +

Z or Y + Z or X + Y + Z) and their amount we start with, the ratio,

]

Y

[

]

X

[

]

Z

[

is always

constant at a given temperature. This really looks amazing. Isn’t it? Let us see, how such

a thing is possible.

We have learnt that at the equilibrium, rate of forward and reverse reactions are equal

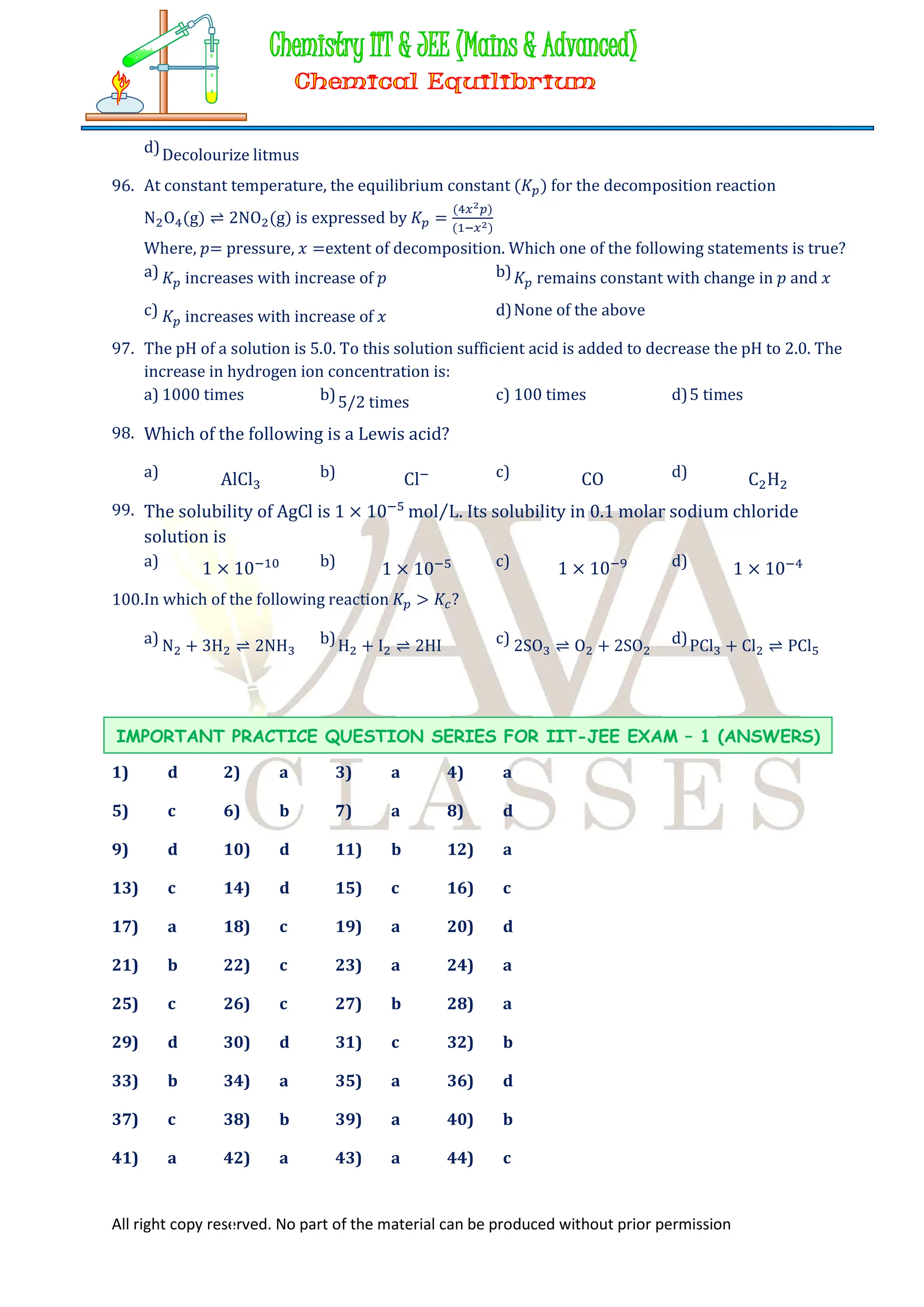

and we also know the law of mass action. Using this, we can write

Rate of forward reaction [X] [Y]

Rate of forward reaction = kf [X] [Y]

where kf is the rate constant for the forward reaction.

Similarly, rate of reverse reaction [Z]

Rate of reverse reaction = kr [Z]

where kr is the rate constant for the reverse reaction.

At equilibrium,

Rate of forward reaction = Rate of reverse reaction.

kf [X] [Y] = kr [Z]

]

Y

[

]

X

[

]

Z

[

k

k

r

f

Since, kf and kr are constants at a given temperature, so their ratio

r

f

k

k

would also be a

constant, referred as Keq.

]

Y

[

]

X

[

]

Z

[

Keq

As Keq is the ratio of rate constants for forward and reverse reaction, so the value of Keq

would always be a constant and will not depend on the species we have started with and

their initial concentrations.

The given expression involves all variable terms (variable term means the concentration

of the involved species changes from the start of the reaction to the stage when

equilibrium is reached), so the ratio

]

Y

[

]

X

[

]

Z

[

can also be referred as KC.

EQUILIBRIUM CONSTANT, 𝑲𝒆𝒒 , 𝑲𝑪 , 𝑲𝑷 𝑨𝑵𝑫 𝑲𝑷𝑪

4](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/chemicalequilibrium-240508121455-3fc1524e/75/Equilibrium-in-Physical-Processes-Class-11-Free-Study-Material-PDF-5-2048.jpg)

![All right copy reserved. No part of the material can be produced without prior permission

]

Y

[

]

X

[

]

Z

[

KC

Thus, for the given equilibrium, it seems that Keq and KC are same but in actual practice

for some other equilibrium, they are not same.

Assuming that the gases X, Y and Z behave ideally, we can use ideal gas equation for

them.

PV = nRT

cRT

RT

V

n

P

RT

P

c

RT

P

]

Z

[

and

RT

P

]

Y

[

;

RT

P

]

X

[ Z

y

x

RT

P

RT

P

RT

P

K

Y

X

Z

C =

Y

X

Z

P

P

RT

P

Y

X

Z

C

P

P

P

RT

K

The LHS of the above expression is a constant since KC , R and T, all are constant.

This implies that RHS is also a constant, which is represented by KP.

Y

X

Z

P

P

P

P

K

Thus, expression of KP involves partial pressures of all the involved species and

represents the ratio of partial pressures of products to reactants of an equilibrium

reaction.

(ii) Now, let us change the phase of reactant X from gaseous to pure solid. Then the

equilibrium reaction can be shown as

X(s) + Y(g) Z(g)

Its equilibrium constant (Keq) would be

]

Y

[

]

X

[

]

Z

[

Keq

Concentration of Y and Z is their respective number of moles per unit volume of the

container (as the volume occupied by the gas is equal to the volume of the container).

The concentration of X is the number of moles of X per unit volume of solid. As we know,

the concentration of all pure solids (and pure liquids) is a constant as it is represented by

d/M (where d and M represents its density and molar mass). This ratio of d/M will be a

constant whether X is present initially or at equilibrium. This means that the concentration of X

is not varying, but is a constant, which can be merged with Keq to give another constant, called

KC.

]

Y

[

]

Z

[

]

X

[

Keq ](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/chemicalequilibrium-240508121455-3fc1524e/75/Equilibrium-in-Physical-Processes-Class-11-Free-Study-Material-PDF-6-2048.jpg)

![All right copy reserved. No part of the material can be produced without prior permission

]

Y

[

]

Z

[

KC

Thus expression of KC involves only those species whose concentration changes during

the reaction.

The distinction between Keq and KC is that the expression of Keq involves all the

species (whether they are pure solids, pure liquids, gases, solvents or solutions)

while the KC expression involves only those species whose concentration is a

variable (like gases and solutions). Thus, expression of KC is devoid of pure

components (like pure solids and pure liquids) and solvents.

Y

Z

Y

Z

C

P

P

RT

P

RT

P

K

Since, LHS of the expression is a constant, so the ratio

Y

Z

P

P

would also be a constant,

represented by KP.

Y

Z

P

P

P

K

(iii)Now, let us change the phase of reactant X from pure solid to solution and add another

gaseous product. The equilibrium reaction can now be represented as

X(soln.) + Y(g) Z(g) + A(g)

]

Y

[

]

X

[

]

A

[

]

Z

[

Keq

We have seen above that concentration of Y, Z and A is a variable but what about the

concentration of X now. Let us see. X in solution phase means some moles of X (solute)

are dissolved in a particular solvent. The concentration of X is thus given as the number

of moles of X per unit volume of solution(volume of the solution has major contribution

from the volume of solvent and the volume of solute hardly contributes to it). Let the

number of moles of X taken initially are ‘a’, which are dissolved in ‘V’ litre of solvent. So,

the initial concentration of X is

V

a

. Now at equilibrium, the moles of X reacted with Y be

‘x’. Thus the concentration of X now becomes

V

a x

. This shows that the concentration

of X changes during the reaction and X is thus a variable.

Thus, given expression of Keq involve all variable terms, so the ratio

]

Y

[

]

X

[

]

A

[

]

Z

[

can also be

referred as KC.

]

Y

[

]

X

[

]

A

[

]

Z

[

KC

Now, if we try to express the concentration of X, Y, Z and A in terms of partial pressures,

we would be able to do it only for Y, Z and A but not for X, since it is a solution. As the

concentration of X cannot be expressed in terms of its pressure or vapour pressure and](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/chemicalequilibrium-240508121455-3fc1524e/75/Equilibrium-in-Physical-Processes-Class-11-Free-Study-Material-PDF-7-2048.jpg)

![All right copy reserved. No part of the material can be produced without prior permission

constants, so it should be kept as concentration term only in the equilibrium constant

expression.

RT

P

]

X

[

P

P

RT

P

]

X

[

RT

P

RT

P

K

Y

A

Z

Y

A

Z

C

Y

A

Z

C

P

]

X

[

P

P

)

RT

(

K

The LHS of the expression is a constant (as KC, R and T all are constant), which implies

that the RHS will also be a constant. But RHS of the expression can neither be called KP

(as all are not partial pressure terms) nor KC (as all are not concentration terms), so such

expression that involves partial pressure and concentration terms both are referred as

KPC.

Y

A

Z

C

P

P

]

X

[

P

P

K

Thus, KP can exist only for that equilibrium which satisfies these two conditions.

(a) At least one of the reactant or product should be in gaseous phase and

(b) No component of the equilibrium should be in solution phase (because when

solution is present, the equilibrium constant would be called KPC).

(iv)Let us consider a different equilibrium reaction of the type,

n1A(g) + n2B(g) m1C(g) + m2D(g)

The equilibrium constant, Keq would be

2

1

2

1

n

n

m

m

eq

]

B

[

]

A

[

]

D

[

]

C

[

K

Since, in this expression all the terms involved are variables, so the ratio

2

1

2

1

n

n

m

m

]

B

[

]

A

[

]

D

[

]

C

[

would also be a constant called Kc.

2

1

2

1

n

n

m

m

C

]

B

[

]

A

[

]

D

[

]

C

[

K

The concentration terms can be replaced by

RT

P

for each gaseous species.

Thus,

2

n

B

1

n

A

2

m

D

1

m

C

C

RT

P

RT

P

RT

P

RT

P

K

Rearranging the expression gives

2

1

2

1

2

1

2

1

n

B

n

A

m

D

m

C

)

n

n

(

)

m

m

(

C

)

P

(

)

P

(

)

P

(

)

P

(

)

RT

(

K

…..(i)

The LHS of the expression is a constant since KC, R, T and all stoichiometric coefficients

are constant. So, RHS of the expression would also be a constant called as KP (as the

RHS involved all partial pressure terms).](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/chemicalequilibrium-240508121455-3fc1524e/75/Equilibrium-in-Physical-Processes-Class-11-Free-Study-Material-PDF-8-2048.jpg)

![All right copy reserved. No part of the material can be produced without prior permission

The reaction quotient is defined as the ratio of concentration of the reacting species at any point

of time other than the equilibrium stage. It is represented by Q. Thus, inserting the starting concentrations

of H2, I2 and HI in the equilibrium constant expression gives

)

146

.

0

(

)

243

.

0

(

)

98

.

1

(

]

[

]

H

[

]

H

[

Q

2

0

2

0

2

2

0

I

I

= 110.5

where the subscript 0 indicates initial concentrations (before equilibrium is reached).

As we know that every reaction has a tendency to attain equilibrium, so Q value should approach

Kc value. In the present case, Q value is greater than Kc value, so value of Q can approach Kc value only

when HI starts converting into H2 and I2. Thus, when Q > Kc, the net reaction proceeds from right to left to

reach equilibrium.

To determine the direction in which the net reaction will proceed to achieve equilibrium, we

compare the values of Q and Kc. The three possible cases are as follows:

(a) Q > Kc: For such a system, products must be converted to reactants to reach equilibrium. The

system proceeds from right to left (consuming products, forming reactants) to reach equilibrium.

(b) Q = Kc: The initial concentrations are the equilibrium concentrations. So, the system is already

at equilibrium.

(c) Qc < Kc: For such a system, reactants must be converted to products to reach equilibrium. The

system proceeds from left to right (consuming reactants, forming products) to attain equilibrium.

7.1 NATURE OF REACTANTS AND/OR PRODUCTS

The value of equilibrium constant depends on the nature of reactants as well as on the products. By

changing reactant(s) or product(s) of a reaction, the equilibrium constant of the reaction changes.

For example,

N2(g) + O2(g) 2NO(g) ;

]

O

[

]

N

[

]

NO

[

K

2

2

2

1

C

N2(g) + 2O2 2NO2(g) ; 2

2

2

2

2

2

C

]

O

[

]

N

[

]

NO

[

K

Although the reactants are same in the two reactions but the products being different, the value of

equilibrium constant for the two reactions will be different. If we start with ‘a’ and ‘b’ moles of N2 and O2

respectively in both the reactions, carried out in same vessel (V litre capacity), the extent of two reactions

occurring will be different and thus, the KC for the two reactions differ.

Similarly for reactions,

H2(g) + I2(g) 2HI(g)

H2(g) + Cl2(g) 2HCl(g)

The values of the equilibrium constant for the two reactions will be completely different as one of

the reactant in the two reactions is different.

7.2 TEMPERATURE

The variation of equilibrium constant with temperature is given by the relation

log .

T

1

T

1

R

303

.

2

H

K

K

2

1

1

2

This can be obtained by the help of Arrhenius equation.

The Arrhenius equation for the rate constant of forward reaction is

kf =

RT

/

)

f

(

a

E

f e

A

………(2)

FACTORS AFFECTING EQUILIBRIUM CONSTANT

7](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/chemicalequilibrium-240508121455-3fc1524e/75/Equilibrium-in-Physical-Processes-Class-11-Free-Study-Material-PDF-10-2048.jpg)

![All right copy reserved. No part of the material can be produced without prior permission

(a) When H is positive (endothermic reactions), an increase in temperature (T2 > T1) will make

2

T

K > 1

T

K , i.e. the reaction goes more in the forward direction and with decrease in

temperature, reaction goes in reverse direction.

(b) When H is negative (exothermic reactions), an increase in temperature (T2 > T1), will take

2

T

K < 1

T

K i.e., the reaction goes in the reverse direction and with decrease in temperature,

reaction goes in the forward direction.

(c) The calculation of equilibrium constant from kinetic consideration is only one of the many

approaches. Since equilibrium constant is a thermodynamic quantity its definition and

calculation involve detailed thermodynamical consideration which is beyond the scope of IIT

JEE syllabus.

7.3 STOICHIOMETRY OF THE EQUILIBRIUM REACTION

The value of KP and KC depends upon the stoichiometry of reaction since the law of mass reaction

makes use of the given stoichiometric coefficients of the reaction.

N2(g) + 3H2(g) 2NH3(g)

KC =

3

2

2

2

3

H

N

NH

………(i)

)

g

(

H

2

3

)

g

(

N

2

1

2

2 NH3(g)

C

K = 2

/

3

2

2

/

1

2

3

]

H

[

]

N

[

]

NH

[

………(ii)

From equation (i) and (ii)

C

C K

K

Thus, in general if an equilibrium reaction is multiplied by ‘n’, the equilibrium constant of the new

reaction would become nth

power of the equilibrium constant of old reaction.

(KC)new = n

old

C )

K

(

7.4 MODE OF WRITING A CHEMICAL EQUATION

The value of KP and KC also depend on the method of representing a chemical equation.

For example,

N2(g) + 3H2(g) 2NH3(g)

KC =

3

2

2

2

3

H

N

NH

When the equilibrium reaction is reversed,

2NH3(g) N2(g) + 3H2(g)

C

K

=

C

2

3

3

2

2

K

1

]

NH

[

]

H

[

]

N

[

Now, if we write the equilibrium reaction as,

NH3(g) ½N2(g) + 3/2 H2(g)

C

K

=

C

3

2

/

3

2

2

/

1

2

K

1

]

NH

[

]

H

[

]

N

[

DEGREE OF DISSOCIATION

8](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/chemicalequilibrium-240508121455-3fc1524e/75/Equilibrium-in-Physical-Processes-Class-11-Free-Study-Material-PDF-12-2048.jpg)

![All right copy reserved. No part of the material can be produced without prior permission

at equil.

V

a x

V

b x

V

2x

KC =

x

x

x

x

x

x

2

b

a

4

V

b

V

a

V

2

]

[

]

H

[

]

H

[

2

2

2

2

I

I

Let PT be the total pressure at the equilibrium.

T

T

2

T

2

2

H

2

H

P

P

b

a

b

P

b

a

a

P

b

a

2

)

P

(

)

P

(

)

P

(

K

x

x

x

I

I

=

x

x

x

b

a

4 2

Thus, Kp = Kc

Also from the relation, Kp = Kc(RT)n

Since, n for this equilibrium reaction is zero,

Kp = Kc

Illustration 1

Question: In an experiment it was found that when 20.55 moles of hydrogen were heated with

31.89 moles of iodine at 440C, the equilibrium mixture contained 2.06 moles of

hydrogen, 13.40 moles of iodine and 36.98 moles of HI. Calculate the equilibrium

constant for the reaction H2(g) + I2(g) 2HI(g).

Solution: In the problem, initial moles of H2 and I2 are given. The moles of H2, I2 and HI are also given

at equilibrium, so the initial moles are not needed in the problem to calculate Kc. Let the

volume of the container be ‘V’ litre.

KC =

40

.

13

06

.

2

98

.

36

V

40

.

13

V

06

.

2

V

98

.

36

]

[

]

H

[

]

H

[ 2

2

2

2

2

I

I

= 49.54

Illustration 2

Question: A sample of HI was found to be 22% dissociated when equilibrium was reached. What

will be the degree of dissociation if hydrogen is added in the proportion of 1 mole for

every mole of HI originally present, the temperature and volume of the system being

kept constant?

Solution: The degree of dissociation () is the fraction of 1 mole of HI that has dissociated under the

given conditions. If the % dissociation of HI is 22, the degree of dissociation is

100

22

= 0.22.

2HI(g) H2(g) + I2(g)

Moles at equil. 1 /2 /2

1 0.22 = 0.78 0.11 0.11

KC =

2

2

2

78

.

0

11

.

0

11

.

0

]

H

[

]

[

]

H

[

I

I2

= 0.0199](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/chemicalequilibrium-240508121455-3fc1524e/75/Equilibrium-in-Physical-Processes-Class-11-Free-Study-Material-PDF-14-2048.jpg)

![All right copy reserved. No part of the material can be produced without prior permission

Let us now add 1 mole of hydrogen when we start with 1 mole of HI. Let x be the

degree of dissociation.

2HI(g) H2(g) + I2(g)

Moles at equil. 1 x

1

2

x

2

x

KC =

2

2

2

1

2

1

2

]

H

[

]

[

]

H

[

x

x

x

I

I2

= 0.0199

x = 0.037 or –2.4 (not admissible)

Degree of dissociation = 0.037

% of dissociation = 3.7

(Introduction of H2 suppresses the dissociation of HI)

(ii) Thermal dissociation of PCl5

When PCl5 is heated in a closed vessel at a steady temperature (above 200C), the

following equilibrium is established.

PCl5(g) PCl3(g) + Cl2(g)

Moles at equil. 1

Let be the degree of dissociation. Then at equilibrium we will have (1 – ) mole of PCl5,

mole of PCl3 and mole of Cl2. If ‘V’ litres is the capacity of the vessel, then molar

concentration of various species would be

[PCl5] =

1

V

; [PCl3] =

V

; [Cl2] =

V

KC =

V

1

V

V

]

PCl

[

]

Cl

[

]

PCl

[

5

2

3

=

2

1

V( )

Let PT be the total pressure of the equilibrium system.

KP =

T

T

T

5

PCl

2

Cl

3

PCl

P

1

1

P

1

P

1

P

P

P

= 2

T

2

1

P

KP KC (since n is not zero)

Illustration 3

Question: 0.1 mole of PCl5 is vapourized in a litre vessel at 200C. What will be the concentration

of chlorine at equilibrium if the equilibrium constant KC for the dissociation of PCl5 at

this temperature is 0.0414?

Solution: PCl5(g) PCl3(g) + Cl2(g)

Moles at equil. 1 x x x

Let x moles of chlorine be present at equilibrium

[PCl5] =

1

1

.

0 x

= 0.1 – x ; [PCl3] = x ; [Cl2] = x

KC = 0.0414 =

]

PCl

[

]

Cl

[

]

PCl

[

5

2

3

=

x

x

1

.

0

2](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/chemicalequilibrium-240508121455-3fc1524e/75/Equilibrium-in-Physical-Processes-Class-11-Free-Study-Material-PDF-15-2048.jpg)

![All right copy reserved. No part of the material can be produced without prior permission

x = 0.0469 moles/litre

[Cl2] = 0.0469 moles/litre

Illustration 4

Question: What will be the degree of dissociation of PCl5 when 0.1 mole of PCl5 is placed in a 3 L

vessel containing chlorine at 0.5 atm pressure and 250C? (KP = 1.78)

Solution: KP =

5

2

3

PCl

Cl

PCl

P

P

P

= 1.78

Let x be the amount of PCl5 dissociated at equililbrium.

V

RT

P 3

PCl

x

;

V

RT

P 2

Cl

x

+ 0.5 ;

V

RT

)

1

.

0

(

P 5

PCl

x

1.78 =

V

RT

)

1

.

0

(

5

.

0

V

RT

V

RT

x

x

x

=

x

x

x

1

.

0

5

.

0

3

523

082

.

0

x = 0.0574 mole

Degree of dissociation () of PCl5 is the fraction of 1 mole that has dissociated.

=

1

.

0

0574

.

0

= 0.574.

(iii) Thermal dissociation of dinitrogen tetroxide

Between 22C and 150C, N2O4 undergoes thermal dissociation and the gas mixture

consists of N2O4 and NO2 in reversible equilibrium.

N2O4(g) 2NO2(g) (endothermic)

If 1 mol of N2O4 is enclosed in a vessel of volume ‘V’ litre and at equilibrium, is the

degree of dissociation of N2O4, then

[N2O4] =

1

V

; [NO2] =

2

V

KC =

V

1

V

2

]

O

N

[

]

NO

[

2

4

2

2

2

4

1

2

V( )

T

2

T

4

O

2

N

2

2

NO

P

P

1

1

P

1

2

)

P

(

)

P

(

K = 2

T

2

1

P

4

where PT is the total equilibrium pressure.

KP KC (since n is not zero)

Illustration 5

Question: The equilibrium constant KP for the reaction N2O4(g) 2NO2(g) at 497C is found

to be 636 mm Hg. If the pressure of the gas mixture is 182 mm, calculate the percentage

dissociation of N2O4. At what pressure will it be half dissociated?

Solution: KP = 2

T

2

1

P

4

](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/chemicalequilibrium-240508121455-3fc1524e/75/Equilibrium-in-Physical-Processes-Class-11-Free-Study-Material-PDF-16-2048.jpg)

![All right copy reserved. No part of the material can be produced without prior permission

636 = 2

2

1

182

4

636 – 6362

= 7282

13642

= 636

2

=

636

1364

= 0.4663 ; = 4663

.

0 = 0.6829

% dissociation of N2O4 = 0.6829 100 = 68.29

When the gas is half dissociated, = 0.5

Let the pressure be T

P mm Hg.

636 =

2

T

2

)

5

.

0

(

1

P

)

5

.

0

(

4

T

P = 477 mm

(iv) Synthesis of ammonia (Haber’s process)

N2(g) + 3H2(g) 2NH3(g) ; H = 46 kJ mol1

Suppose we start with 1 mole of nitrogen and 3 moles of H2 in a vessel of capacity ‘V’

litres and heat the mixture at a steady temperature (250C) under pressure.

Let x moles of N2 react. Then

N2(g) + 3H2(g) 2NH3(g)

Molar conc. at

V

1 x

V

)

1

(

3 x

V

2x

equilibrium

KC = 3

2

3

2

2

2

3

V

)

1

(

3

V

1

V

2

]

H

[

]

N

[

]

NH

[

x

x

x

= 4

2

2

)

1

(

27

V

4

x

x

KP =

3

2

H

2

N

2

3

NH

P

P

P

= 3

T

T

2

T

P

2

4

)

1

(

3

P

2

4

)

1

(

P

2

4

2

x

x

x

x

x

x

=

2

T

4

2

2

P

)

1

(

27

)

2

4

(

4

x

x

x

where PT is the total pressure at equilibrium.

KP KC (as n is nonzero)

Illustration 6

Question: For the reaction

N2(g) + 3H2(g) 2NH3(g) ; H = 46 kJ mol1

Calculate the value of KP. Given KC = 0.5 lit2

mol2

at 400C.

Solution: KP = KC(RT)n

n = 2 – 4 = 2](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/chemicalequilibrium-240508121455-3fc1524e/75/Equilibrium-in-Physical-Processes-Class-11-Free-Study-Material-PDF-17-2048.jpg)

![All right copy reserved. No part of the material can be produced without prior permission

KP = 0.5(0.082 673)2

= 2

)

673

082

.

0

(

5

.

0

= 1.641 104

.

Illustration 7

Question: 1 mole of nitrogen is mixed with 3 moles of hydrogen in a 4 L container. If 0.25% of N2

is converted into ammonia by the following reaction

N2(g) + 3H2(g) 2NH3(g)

Calculate the equilibrium constant KC in concentration units. What will be the value of

KC for the following equilibrium?

1

2

N2(g) +

3

2

H2(g) NH3(g)

Solution: N2 + 3H2 2NH3

Initial 1 3 0 moles

Let x moles of N2 react at equilibrium.

Then 1 – x 3 – 3x 2x moles at equilibrium

KC =

3

2

V

3

3

V

1

V

2

x

x

x

=

4

2

2

)

1

(

27

V

4

x

x

=

4

2

2

)

0025

.

0

1

(

27

4

)

0025

.

0

(

4

KC = 1.496 105

litre2

mole2

KC =

3

2

2

2

3

]

H

[

]

N

[

]

NH

[

For the equilibrium 2

2 H

2

3

N

2

1

NH3, the equilibrium constant would be

2

/

3

2

2

/

1

2

3

c

]

H

[

]

N

[

]

NH

[

K

=

c

K 5

c 10

496

.

1

K

= 3.86 103

litre mol1

9.2 HOMOGENEOUS EQUILIBRIA IN SOLUTION PHASE

Formation of ethyl acetate

This equilibrium can be represented by the equation

C2H5OH(l) + CH3COOH(l) CH3COOC2H5(l) + H2O(l)

Although for each species, we write l in the parenthesis but they are not pure liquids. Once

the liquids are mixed, they form a homogeneous solution. Thus, the concentration of each species

changes during establishment of equilibrium. If the system behaved ideally,

]

COOH

CH

[

]

OH

H

C

[

]

O

H

[

]

H

COOC

CH

[

K

3

5

2

2

5

2

3

c

Let the total volume of the solution be ‘V’ litre and the initial number of moles of acetic

acid and that of ethanol be ‘a’ and ‘b’ respectively.

Let ‘x’ moles of acetic acid react at equilibrium. Then ‘x’ moles of ethyl acetate and ‘x’

moles of water would be formed. At equilibrium,

[CH3COOH] =

V

a x

; [C2H5OH] =

V

b x

; [CH3COOC2H5] =

V

x

; [H2O] =

V

x](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/chemicalequilibrium-240508121455-3fc1524e/75/Equilibrium-in-Physical-Processes-Class-11-Free-Study-Material-PDF-18-2048.jpg)

![All right copy reserved. No part of the material can be produced without prior permission

KC =

)

b

(

)

a

(

V

)

b

(

V

)

a

(

V

V

2

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

Illustration 8

Question: Determine the amount of ester present under equilibrium when 3 moles of ethyl alcohol

react with 1 mole of acetic acid, when equilibrium constant of the reaction is 4.

Solution: CH3COOH + C2H5OH CH3COOC2H5 + H2O

1 – x 3 – x x x

KC = 4 =

)

3

(

)

1

( x

x

x

x

= 2

2

4

3 x

x

x

3x2

– 16x + 12 = 0

x = 0.903 or 4.43 (inadmissible)

Amount of ester at equilibrium = 0.903 mole.

9.3 EQUILIBRIUM CONSTANT FOR VARIOUS HETEROGENEOUS EQUILIBRIA

Heterogeneous equilibrium results from a reversible reaction involving reactants and products that

are in different phases. The law of mass action applicable to a homogeneous equilibrium is also

applicable to a heterogeneous system.

(a) Decomposition of solid CaCO3 into solid CaO and gaseous CO2

Let ‘a’ moles of CaCO3 are taken in a vessel of volume ‘V’ litre at temperature ‘T’ K.

CaCO3(s) CaO(s) + CO2(g)

Moles initially a 0 0

Moles at equilibrium a x x x

Keq =

]

CaCO

[

]

CO

[

]

CaO

[

3

2

As CaCO3 and CaO(s) are pure solids, so their d/M is a constant and their concentrations do not

change as long as they are present. Thus the equilibrium expression can be rearranged as

Keq ]

CO

[

]

CaO

[

]

CaCO

[

2

3

It can be seen that left hand side of the equation is a constant represented by Kc.

Kc = [CO2] =

V

x

……..(i)

Assuming CO2 gas to behave ideally at the temperature & pressure of the reaction, the molar

concentration of CO2 can be written using ideal gas equation as

RT

P 2

CO

.

Kc =

RT

P 2

CO

Kc(RT) = 2

CO

P

Since Kc, R and T are constants, their product will also be a constant referred as Kp.

Kp = 2

CO

P =

V

RT

x

……..(ii)

From equation (i) and (ii), it is clear that whenever the equilibrium would be attained at ‘T’

K, in a vessel of volume ‘V’ litre, the moles of CO2 present at equilibrium should be

x (which can exert a pressure equal to )

P 2

CO If rather than starting with ‘a’ mole of CaCO3, we](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/chemicalequilibrium-240508121455-3fc1524e/75/Equilibrium-in-Physical-Processes-Class-11-Free-Study-Material-PDF-19-2048.jpg)

![All right copy reserved. No part of the material can be produced without prior permission

start with x moles of CaCO3 in the vessel of volume ‘V’ at ‘T’K, then the entire CaCO3 would

have decomposed to give CO2 but the equilibrium can not be maintained as there would be no

CaCO3 left. Further if the moles of CaCO3 taken in the same vessel at same temperature were less

than x, the equilibrium would never be attained. Thus, any amount (moles) of CaCO3 more than x

would be sufficient to establish the equilibrium. So the minimum moles of CaCO3 required would

be x, as any moles more than this would be sufficient to establish the equilibrium. So the minimum

moles of CaCO3 required to attain equilibrium under given conditions would be x.

The given equilibrium can be made to move in the forward direction by either removing

some moles of CO2 or by increasing the volume of the container or by increasing the temperature

of the reaction (as the reaction is endothermic). Addition of solid CaCO3 or CaO to the equilibrium

mixture will not affect the equilibrium at all.

For such equilibria, at any temperature, there will be a fixed value of the pressure of CO2,

which is called as dissociation pressure. The dissociation pressure of heterogeneous equilibria is

defined as the total pressure exerted by the gaseous species in equilibrium with the solid species.

The relation giving the variation of Kp with temperature is

log

2

1

1

T

p

2

T

p

T

1

T

1

R

303

.

2

H

)

K

(

)

K

(

Illustration 9

Question: Consider the following heterogeneous equilibrium,

CaCO3(s) CaO(s) + CO2(g).

At 800°C, the pressure of CO2 is 0.236 atm. Calculate

(a) Kp and (b) Kc for the equilibrium reaction at this temperature.

Solution: For the given equilibrium, partial pressure of CO2 is nothing but equal to Kp.

Kp = 2

CO

p = 0.236 atm

For an equilibrium reaction,

Kp = Kc(RT)n

As n = 1, so Kc =

1073

0821

.

0

236

.

0

RT

Kp

Kc = 2.68 103

moles/litre

(b) Reaction of solid phosphorous with gaseous Cl2 to form liquid PCl3

P4(s) + 6Cl2(g) 4PCl3(l)

The equilibrium constant is given by

6

2

4

4

3

eq

Cl

P

PCl

K

Since, pure solids and pure liquids do not appear in the equilibrium constant expression, thus

expression can be rearranged as

6

2

4

3

4

eq

Cl

1

PCl

P

K

Kc = 6

2 ]

Cl

[

1

Alternatively, we can express the equilibrium constant in terms of the pressure of Cl2.

Kp = 6

2

Cl )

p

(

1

(iii) Dissociation of ammonium hydrogen sulfide](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/chemicalequilibrium-240508121455-3fc1524e/75/Equilibrium-in-Physical-Processes-Class-11-Free-Study-Material-PDF-20-2048.jpg)

![All right copy reserved. No part of the material can be produced without prior permission

Let the moles of NH4HS(s) taken in a vessel of volume ‘V’ litre be ‘a’ at temperature ‘T’K.

At equilibrium, x moles of NH4HS dissociates to give NH3(g) and H2S(g).

NH4HS(s) NH3(g) + H2S(g)

Moles initially a 0 0

Moles of equilibrium a x x x

Keq =

]

HS

NH

[

]

S

H

[

]

NH

[

4

2

3

As the concentration of NH4HS is a constant, so it can be merged with Keq to get KC.

Keq [NH4HS] = [NH3] [H2S]

KC = [NH3] [H2S] =

2

V

V

V

x

x

x

Assuming H2S and NH3 to behave ideally at the given temperature and pressure of the

reaction, the molar concentration of the gas can be written as .

RT

P

[NH3] = [H2S] =

RT

P

RT

P S

2

H

3

NH

KC =

RT

P

RT

P S

2

H

3

NH

KC(RT)2

= S

2

H

3

NH P

P

Since, LHS of the expression is a constant, it can be represented by another constant, KP.

KP = .

P

P S

H

NH 2

3

If the dissociation pressure measured for NH4HS be PT atm, then

S

H

NH 2

3

P

P =

2

PT

KP =

4

P

2

P

2

P

2

T

T

T

We have so far considered relatively simple equilibrium reactions. Let us take a slightly

complicated situation, in which the product molecules(s) in one equilibrium system are involved in a

second equilibrium process.

A(g) + B(g) C(g) + D(g) ;

]

B

[

]

A

[

]

D

[

]

C

[

K 1

C

C(g) + E(g) F(g) + G(g) ;

]

E

[

]

C

[

]

G

[

]

F

[

K 2

C

Overall reaction: A(g) + B(g) + E(g) D(g) + F(g) + G(g) ;

]

E

[

]

B

[

]

A

[

]

G

[

]

F

[

]

D

[

K 3

C

In this case, one of the product molecule, C(g) of the first equilibrium reaction combines with E(g)

to give F(g) and G(g) in another equilibrium reaction, so in the overall reaction, C(g) will not appear on

either side.

MULTIPLE EQUILIBRIA

10](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/chemicalequilibrium-240508121455-3fc1524e/75/Equilibrium-in-Physical-Processes-Class-11-Free-Study-Material-PDF-21-2048.jpg)

![All right copy reserved. No part of the material can be produced without prior permission

The equilibrium constant )

K

( 3

C of the overall reaction can be obtained if we take the product of the

expressions of )

K

( 1

C and )

K

( 2

C .

]

E

[

]

B

[

]

A

[

]

G

[

]

F

[

]

D

[

]

E

[

]

C

[

]

G

[

]

F

[

]

B

[

]

A

[

]

D

[

]

C

[

K

K 2

C

1

C

3

C

2

C

1

C K

K

K

Thus, if a equilibrium reaction can be expressed as the sum of two or more equilibrium

reactions, then the equilibrium constant for the overall reaction is given by the product of the

equilibrium constants of the individual reactions.

When more than one equilibrium are established in a vessel at the same time and any one of the

reactant or product is common in more than one equilibrium, then the equilibrium concentration of the

common species in all the equilibrium would be same.

For example, if we take CaCO3(s) and C(s) together in a vessel of capacity ‘V’ litre and heat it at

temperature ‘T’ K, then CaCO3 decomposes to CaO(s) and CO2(g). Further, evolved CO2 combines with

the C(s) to give carbon monoxide. Let the moles of CaCO3 and carbon taken initially be ‘a’ and ‘b’

respectively.

CaCO3(s) CaO(s) + CO2(g)

Moles at equilibrium a x x (x y)

CO2(g) + C(s) 2CO(g)

Moles at equilibrium (x y) (b y) 2y

Thus, as CO2 is common in both the equilibrium so its concentration is same in both the

equilibrium constant expressions.

Equilibrium constant for first equilibrium, 1

C

K = [CO2] =

V

y

x

Equilibrium constant for second equilibrium, 2

C

K =

2

2

CO

CO

=

)

y

V

V

2

(

2

(x

y)2

=

y)

V(x

4y2

POINTS TO BE REMEMBERED FOR WRITING EQUILIBRIUM CONSTANT EXPRESSIONS

The concentration of the reacting species in the solution phase is expressed in mol/litre.

The concentration of the reacting species in the gaseous phase can be expressed either in mol/litre

or in atm.

The concentration of pure solid, pure liquids (in heterogeneous equilibria) and solvents

(in homogeneous equilibria) are constant and do not appear in the equilibrium constant expression

of a reaction.

Kp and Kc are related as, Kp = Kc(RT)n

where n = number of moles of gaseous product number

of moles of gaseous reactant.

It is not customary to write units of equilibrium constants (Kp and Kc) but when mentioned, the

units of Kp are (atm)n

and units of Kc are .

litre

moles

n

In quoting the value of equilibrium constant, we must specify the balanced equation and the

temperature at which equilibrium is established.

If a reaction can be expressed as the sum of two or more reactions, the product of the equilibrium

constants of the individual reactions gives the equilibrium constant for the overall reaction.

SIMULTANEOUS EQUILIBRIA

11](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/chemicalequilibrium-240508121455-3fc1524e/75/Equilibrium-in-Physical-Processes-Class-11-Free-Study-Material-PDF-22-2048.jpg)

![All right copy reserved. No part of the material can be produced without prior permission

Since n = 0, there is no effect on changing the pressure. High temperature favours forward

reaction.

Dissociation of PCl5

PCl5(g) PCl3(g) + Cl2(g) ; H = +ve

Conditions favourable for forward reactions are (i) low pressure, (ii) high temperature. Oxidation

of carbon monoxide by steam:

CO(g) + H2O(g) CO2(g) + H2(g) ; H = –ve

n = 0 and so pressure has no effect. Low temperature favours forward reaction and so by

employing excess of steam.

Illustration 10

Question:For the gaseous equilibrium at high temperature,

PCl5(g) PCl3(g) + Cl2(g); H = 87.9 kJ

explain the effect upon the material distribution of (a) increased temperature (b)

increased pressure (c) higher concentration of Cl2 (d) higher concentration of PCl5 and

(e) presence of a catalyst.

Solution:(a) When the temperature of a system in equilibrium is raised (by addition of heat), the

equilibrium is displaced in the direction which absorbs heat. Hence increasing the

temperature will cause more PCl5 to dissociate.

(b) When the pressure of a system in equilibrium is increased, the equilibrium is displaced in the

direction of the smaller volume. One volume each of PCl3 and Cl2, a total of 2 gas volumes

(on the product side) from only 1 volume of PCl5. Hence a pressure increase will promote

the reaction to form more PCl5.

(c) Increasing the concentration of any component will displace the equilibrium in the direction

which tends to lower the concentration of the component added. Increasing the concentration

of Cl2 will result in the consumption of more PCl3 and the formation of more PCl5 and this

action will tend to offset the increased concentration of Cl2.

(d) Increasing the concentration of PCl5 will result in the formation of more PCl3 and Cl2 or

more dissociation of PCl5.

(e) A catalyst accelerates both forward and backward reactions equally. It speeds up the

approach to equilibrium but does not favor reaction in either direction.

The relation between vapour density and the degree of dissociation can be established only for a

gaseous equilibrium whose KP exists. For example,

A(g) nB (g)

Initial conc. c 0

Conc. at equilibrium c(1 ) nc

Total concentration at equilibrium = c c + nc = c [1 + n] = c [1 + (n – 1)]

Assuming that all the gaseous components at equilibrium behave ideally, we can apply ideal gas

equation.

RT

M

w

nRT

PV

P

RT

P

RT

V

w

M

V.D =

P

2

RT

….(i) [since molar mass = 2 V.D]

RELATION BETWEEN VAPOUR DENSITY AND DEGREE OF DISSOCIATION

13](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/chemicalequilibrium-240508121455-3fc1524e/75/Equilibrium-in-Physical-Processes-Class-11-Free-Study-Material-PDF-27-2048.jpg)

![All right copy reserved. No part of the material can be produced without prior permission

As pressure of the system is given by,

V

nRT

P , so putting the value of P in equation (i) gives

V.D =

n

2

V

V

nRT

2

RT

where is the density of the gas or gaseous mixture expressed in g/litre.

If the equilibrium reaction is established in a closed vessel, then vapour density will be inversely

proportional to the number of moles of the gaseous species as the density of the gaseous mixture () is a

constant.

reactant

gaseous

of

moles

Initial

m

equilibriu

at

gases

of

moles

Total

m

equilibriu

at

density

Vapour

density

vapour

Initial

Let the initial vapour density and vapour density at equilibrium be ‘D’ and ‘d’ respectively, then

for the given equilibrium

c

)]

1

n

(

1

[

c

d

D

or )]

1

n

(

1

[

d

D

or )

1

n

(

1

d

D

d

n

d

D

)

1

(

)

(

where ‘n’ represents the number of moles of gaseous product given by 1 mole of the gaseous reactant.

Knowing D, d and n, the degree of dissociation () can be calculated.

The vapour density measurement is used for the determination of degree of dissociation of only

those equilibria in which 1 mole of the gaseous reactant gives more than one mole of gaseous products.

Because when one mole of the gaseous reactant gives only one mole of gaseous product, then ‘D’ and ‘d’

would be same and ‘’ can not be determined.

As you might be aware, every process in nature occurs in order to reduce the energy of a system.

This is because reduced energy state has fewer tendencies to undergo change thereby it brings stability.

When an object falls from a certain height, the process reduces the potential energy of the system. Where

as, if the object is to be taken to a certain height the potential energy increases. That’s why the former

occurs on its own, while for the latter work has to be done.

Chemical reactions too occur with decrease in energy. One might of course wonder how does an

endothermic reaction occur? Well, even endothermic reactions occur with decrease in energy! This

statement may contradict the very definition of endothermic reactions. Not so if you read on.

The energy that decreases in a chemical reaction, which brings about stability, is called Free

Energy. It is the decrease in free energy that causes a reaction to happen. For endothermic reactions also,

the free energy decreases, even though the total energy increases. This can be understood by figuring out

what is free energy?

Free energy of a system, say for example a molecule like CH4, is the total intrinsic electrostatic

potential energy of the system. In a CH4 molecule, there are in total 10 protons

(6 of C and 1 each of H) and 10 electrons (6 of C and 1 each of H). If we were to calculate the total

electrostatic potential energy of the system by calculating the potential energy of all charges due to all

other charges and adding the sum, the result would be the free energy of CH4 molecule.

For this, one needs to know the distance between all the charges, which is not practically possible. But the

concept of free energy is very useful to understand the direction of reactions. Free energy represents the

RELATION BETWEEN FREE ENERGY CHANGE & EQUILIBRIUM CONSTANT

14](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/chemicalequilibrium-240508121455-3fc1524e/75/Equilibrium-in-Physical-Processes-Class-11-Free-Study-Material-PDF-28-2048.jpg)

![All right copy reserved. No part of the material can be produced without prior permission

stability of a system. Lower the value of free energy; more are the attractive forces in the system and

consequently more is the stability. If one were to ask why methane is a tetrahedron then a safe answer

would be that it is the tetrahedral shape that allows methane to have the least possible free energy. With

temperature free energy is likely to change as bond distances and angles may get altered.

Let us consider a reaction,

A + B C + D

Free Energy per mole 3 6 2 5

(in kJ)

No. of mole 2 3 4 1

If we look at this reaction we can see that the total Free Energy on the left is

[2 (3)] + [3 (6)] = 24. On the other hand, the free energy on the right side is [4 (2)] + [1 (5)] = 13.

This means that the left side of the reaction has greater instability than the right side. So to bring about

stability, the free energy lowers itself by moving the reaction to the forward direction. The corollary of this

is that the reverse reaction does not occur because this would bring about instability. As the forward

reaction occurs the number of mole of A & B decreases while that of

C & D increases. This makes the number on the left side smaller and that of the right side bigger. Finally a

stage is reached when the free energy of the left and the right become equal. This is the stage when

equilibrium is established. At this juncture the reverse reaction starts to occur (because free energy while

going reverse is not taking the reaction to the side of instability) with the same speed as that of the forward

reaction.

Therefore, free energy change is zero when the reaction is at equilibrium (G = 0).

When the concentration of all reactants and products is 1 mole/litre, the change in Free Energy is

represented as

0

G

. For the reaction shown

0

G

= 2.

Thus, G is the free energy change at any given concentration of reactants and products.

If all the reactants and products are taken at a concentration of one mol per litre, the free energy change of

the reaction is called

0

G

(standard free energy change). Remember that

0

G

is not necessarily the free

energy change at equilibrium.

G° = 0

f

G

of products 0

f

G

of reactants

and G = Gf of products Gf of reactants.

If G = ve, reaction goes in the forward direction

G = +ve, reaction goes in the backward direction

G = 0, reaction is at equilibrium

It has been proved (proof not required) that

0

G

= RT ln K.

where T is always in Kelvin, and if R is in joules,

0

G

will be in joules, and if R is calories then

0

G

will

be in calories.

[Note: K may either be KC or KP or any other equilibrium constant. The use of this relation between

0

G

and equilibrium constant (K) will also be seen in the lesson “Electrochemistry”.]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/chemicalequilibrium-240508121455-3fc1524e/75/Equilibrium-in-Physical-Processes-Class-11-Free-Study-Material-PDF-29-2048.jpg)

![All right copy reserved. No part of the material can be produced without prior permission

KP =

)]

2

1

(

c

[

)]

1

(

c

[

P

c

2

c

P

P

P

2

T

2

2

2

AB

2

AB

2

B

KP =

2

1

)

1

(

2

P

2

T

3

Since, is small as compared to unity, so 1 ~ 1 and

2

1

~1.

KP =

2

PT

3

(a)

Example 6:

For the equilibrium,

H2O(s) H2O(l)

which of the following statement is true?

(a) The pressure changes do not affect the equilibrium.

(b) More of ice melts, if pressure on the system is increased.

(c) More of liquid freezes, if pressure on the system is increased.

(d) The pressure changes may increase or decrease the degree of advancement of the reaction

depending upon the temperature of the system.

Solution:

For heterogeneous physical equilibrium, with the increase of pressure, equilibrium shifts

in the direction of physical state having higher density. This means that for the equilibrium,

H2O(s) H2O(l), more ice would melt on increasing the pressure of the system as density of

water is more than ice.

(b)

Example 7:

For the reaction,

NH2COONH4(s) 2NH3(g) + CO2(g)

The equilibrium constant Kp = 2. 9 105

atm3

at T K. The total pressure of gases at

equilibrium when 1.0 mole of reactant was heated at T K will be

(a) 0.0194 atm (b) 0.0388 atm

(c) 0.058 atm (d) 0.0667 atm

Solution:

NH2COONH4(s) 2NH3(g) + CO2(g)

Moles initially 1 0 0

Moles at equib. (1 x) 2x x

Total moles of gaseous species at equilibrium = 3x

Equilibrium pressure = PT

3

P

P

,

P

3

2

P T

2

CO

T

3

NH

2

CO

2

3

NH

p P

)

P

(

K =

3

P

P

3

2 T

2

T

27

P

4

10

9

.

2

3

T

5

PT = 0.058 atm](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/chemicalequilibrium-240508121455-3fc1524e/75/Equilibrium-in-Physical-Processes-Class-11-Free-Study-Material-PDF-32-2048.jpg)

![All right copy reserved. No part of the material can be produced without prior permission

(c)

Example 8:

In an equilibrium reaction, x moles of the gaseous reactant ‘A’ decompose to give 1 mole

each of gaseous ‘C’ and ‘D’. If the fraction of A decomposed at equilibrium is independent of

the initial concentration, then the value of x would be

(a) 1 (b) 2 (c) 3 (d) 4

Solution:

The fraction of A decomposed at equilibrium is independent of initial concentration means the

equilibrium constant expression is free from concentration term. The equilibrium reaction is

xA(g) C(g) + D(g)

Initial conc. c 0 0

Conc. at. equil. c(1 )

x

c

x

c

KC =

x

x

x

x

)

1

(

c

c

c

A

D

C

=

x

2

x α)

c(1

c

2

The expression of KC would be free from concentration term only when value of x is 2 as the

power of concentration term in the numerator is 2.

Thus, putting x = 2, gives

2

2

2

C

α)

c(1

4

c

K

= 2

2

α)

(1

4

(b)

Example 9:

At a certain temperature the following equilibrium is established,

CO(g) + NO2(g) CO2(g) + NO(g).

One mole of each of the four gases is mixed in one litre container and the reaction is allowed

to reach equilibrium state. When excess of baryta water is added to the equilibrium mixture,

the weight of white precipitate obtained is 236.4 g. The equilibrium constant, Kc of the

reaction is

(a) 1.2 (b) 2.25

(c) 2.1 (d) 3.6

Solution:

CO(g) + NO2(g) CO2(g) + NO(g)

Moles initially 1 1 1 1

Moles at equib. 1 x 1 x 1 + x 1 + x

CO2 + Ba(OH)2 BaCO3 + H2O

Moles of BaCO3 =

197

4

.

236

= 1.2

Moles of CO2 at equilibrium = 1.2

or, 1 + x = 1.2 ; x = 0.2

25

.

2

8

.

0

2

.

1

1

1

K

2

2

c

x

x

(b)

Example 10:

The approach to the following equilibrium was observed kinetically from both directions.

[PtCl4]2

+ H2O [Pt(H2O)Cl3]

+ Cl

At 25°C, it was found that](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/chemicalequilibrium-240508121455-3fc1524e/75/Equilibrium-in-Physical-Processes-Class-11-Free-Study-Material-PDF-33-2048.jpg)

![All right copy reserved. No part of the material can be produced without prior permission

Δt

PtCl

Δ

2

4

= (3.9 105

s1

) [PtCl4]2

(2.1 103

L mol1

. s1

) [Pt(H2O)Cl3]

[Cl

]

The value of Kc (equilibrium constant) for the complexation of the fourth Cl

by Pt(II) is

(a) 53.8 (b) 50 (c) 60 (d) 63.8

Solution:

At equilibrium, the rate of change of concentration of any species (reactant or product) is zero.

The equilibrium reaction for the complexation of the fourth Cl

by Pt(II) is

[Pt(H2O)Cl3]

+ [Cl

] [PtCl4]2

+ H2O

Keq =

Cl

Cl

)

O

H

(

Pt

O

H

PtCl

3

2

2

2

4

Since, water is a solvent in the given reaction, so its concentration remains constant.

O

H

K

2

eq

=

Cl

Cl

)

O

H

(

Pt

PtCl

3

2

2

4

= KC

In the problem, expression of rate of change of concentration of

2

4

PtCl is given, which at

equilibrium is zero.

t

PtCl

2

4

= (3.9 105

) [PtCl4]2

(2.1 103

) [Pt(H2O)Cl3]

[Cl

] = 0

(3.9 105

) [PtCl4]2

= (2.1 103

) [Pt(H2O)Cl3]

[Cl

]

Cl

Cl

)

O

H

(

Pt

PtCl

3

2

2

4

= KC = 5

3

10

9

.

3

10

1

.

2

= 53.8

(a)

Example 11:

Enough solid NH4HS and LiCl.3NH3 are heated in a closed vessel at 100°C and the following

equilibria are established.

LiCl.3NH3(s) LiCl.NH3(s) + 2NH3(g)

NH4HS(s) NH3(g) + H2S(g)

If Kp for the first equilibrium at 100°C is 9 atm2

and the total pressure of the system is 12

atm, then the Kp for second equilibrium would be

(a)9 atm2

(b) 27 atm2

(c)3 atm2

(d) 81 atm2

Solution:

LiCl.3NH3(s) LiCl.NH3(s) + 2NH3(g)

NH4HS(s) NH3(g) + H2S(g)

Since both equilibria are attained simultaneously, thus

2

NH3

P = 9 3

NH

P = 3 atm

3

NH

P + S

H2

P = 12

S

H2

P = 9 atm

For second equilibrium reaction,

Kp = 3

NH

P S

H2

P = 9 3 = 27 atm2

.

(b)

Example 12:](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/chemicalequilibrium-240508121455-3fc1524e/75/Equilibrium-in-Physical-Processes-Class-11-Free-Study-Material-PDF-34-2048.jpg)

![All right copy reserved. No part of the material can be produced without prior permission

When 800 ml of 1 M AgNO3 solution is mixed with 127 g Cu taken in a vessel of 2 L capacity,

the equilibrium established is 2Ag+

+ Cu(s) 2Ag(s) + Cu2+

. The moles of Cu2+

at

equilibrium are 0.2. The value of equilibrium constant (Kc) would be

(a)1.25 (b)1

(c)0.5 (d)0.4

Solution:

2Ag+

+ Cu(s) 2Ag(s) + Cu2+

Moles initially 0.8 2 0 0

Moles at equilib. 0.8 2x 2 x 2x x

Kc = 2

2

]

Ag

[

]

Cu

[

= 2

V

2

8

.

0

V

x

x

= 2

)

2

(0.8 x

x

V

Kc = 2

)

4

.

0

8

.

0

(

8

.

0

2

.

0

=

4

.

0

4

.

0

8

.

0

2

.

0

= 1.

(b)

Example 13:

A reaction has Kp = 0.33 atm. On decreasing the volume of the container, the reaction would

(a) move forward to reach equilibrium (b) move reverse to reach equilibrium

(c) remain in equilibrium (d) cannot be predicted

Solution:

Kp = 0.33 atm

The unit of Kp shows that reaction is of the type nA(g) (n + 1)B(g)

and Kc =

1

n

B

V

n

n

A

n

V

= n

A

1

n

B

)

n

(

V

)

n

(

and on decreasing the volume of the container, the value of Qc increases and reaction moves in

backward direction.

(b)

Example 14:

For the equilibrium reaction 2HI(g) H2 (g) + I2(g), the degree of dissociation

(a) is constant at a given temperature

(b) depends upon the total pressure of the system

(c) depends upon the initial mole of HI

(d) none of these

Solution:

2HI(g) H2(g) + I2(g)

c

c(1 ) c/2 c/2

Kc = 2

2

2

2

)

α

1

(

c

4

α

c

= 2

2

)

α

1

(

4

α

At constant T, Kc is a constant, so will remain constant.

(a)

Example 15:

In an equilibrium mixture containing N2O4(g) and NO2(g) at a certain temperature, the NO2

is found to be 25% by volume. The molecular weight of the equilibrium mixture is](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/chemicalequilibrium-240508121455-3fc1524e/75/Equilibrium-in-Physical-Processes-Class-11-Free-Study-Material-PDF-35-2048.jpg)

![All right copy reserved. No part of the material can be produced without prior permission

SOLVED SUBJECTIVE EXAMPLES

Example 1:

PCl5(g) PCl3(g) + Cl2(g). Calculate the moles of Cl2 produced at equilibrium when

1.00 mol of PCl5 is heated at 250°C in a vessel having a capacity of 10.0 L. At 250°C,

KC = 0.041 for this dissociation.

Solution:

The equilibrium reaction is

PCl5(g) PCl3(g) + Cl2(g)

Initial conc.

10

1

= 0.1 0 0

Conc. at equilib. 0.1 x x x

KC =

]

PCl

[

]

Cl

[

]

PCl

[

5

2

3

=

)

1

.

0

( x

x

x

= 0.041

2

)

0041

.

0

(

4

)

041

.

0

(

041

.

0 2

x = 0.047

Moles of Cl2 produced at equilibrium = 0.047 10 = 0.47

Example 2:

At 46°C, Kp for the reaction,

N2O4(g) 2NO2(g)

is 0.66 atm. Compute the percent dissociation of N2O4 at 46°C and a total pressure of

380 torr. What are the partial pressures of N2O4 and NO2 at equilibrium?

Solution:

At equilibrium, let the partial pressure of NO2 be P atm and the total pressure be PT atm. Then the

partial pressure of N2O4 would be (PT P) atm.

N2O4(g) 2NO2(g)

KP =

P

P

P

)

P

(

)

P

(

T

2

4

O

2

N

2

2

NO

PT = atm

5

.

0

760

380

0.66 =

P

5

.

0

P2

P2

+ 0.66P 0.33 = 0

Solving quadratic equation in P gives,

P = 0.332 atm.

4

O

2

N

P = 0.5 0.332 = 0.168 atm

2

NO

P = 0.332 atm

Since each mole of N2O4, which dissociates produces 2 mole of NO2, the percent dissociation of

N2O4 is given by

100

2

332

.

0

168

.

0

2

332

.

0

100

O

N

of

pressure

Initial

decreased

O

N

of

pressure

4

2

4

2

= 50%](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/chemicalequilibrium-240508121455-3fc1524e/75/Equilibrium-in-Physical-Processes-Class-11-Free-Study-Material-PDF-39-2048.jpg)

![All right copy reserved. No part of the material can be produced without prior permission

Example 3:

For the gaseous reaction of XO with O2 to form XO2, the equilibrium constant at 398 K is

1.0 104

lit/mole. If 1.0 mole of XO and 2.0 mole of O2 are placed in a 1.0 L vessel and

allowed to come to equilibrium, what will be the equilibrium concentration of each of the

species?

Solution:

The equilibrium reaction is

2XO(g) + O2(g) 2XO2(g)

since the unit of Kc given is lit/mole.

2XO(g) + O2(g) 2XO2(g)

Initial conc.

V

1

V

2

0

Conc. at equilib.

V

2

1 x

V

2 x

V

2x

KC =

2

)

2

1

(

V

4

V

2

V

2

1

V

2

]

O

[

]

XO

[

]

XO

[

2

2

2

2

2

2

2

x

x

x

x

2

1 104

=

2

)

2

1

(

1

4

2

x

x2

Since, the value of equilibrium constant is very small (1 104

), so 2x can be ignored with respect to 1.

1 2x ~ 1

1 104

= 2

4 2

x

x = 7.07 103

We can see that the value of x is very small, so the assumption made was correct as it is within

1.4% of the actual value. Thus, the assumption made is correct and acceptable.

[XO] = 1 0.01414 = 0.985 M

[O2] = 2 0.00707 = 1.992 M

[XO2] = 0.0141 M

Example 4:

At a certain temperature, the equilibrium constant for the gaseous reaction of CO with O2 to

produce CO2 is 5.0 103

lit/mole. Calculate [CO] at equilibrium, if 1.0 mol each of CO and

O2 are placed in a 2.0 L vessel and allowed to come to equilibrium.

Solution:

The equilibrium reaction would involve 2 moles of CO, 1 mole of O2 and 2 moles of CO2 as the

unit of KC is lit/mole.

So the equilibrium equation is

2CO(g) + O2(g) 2CO2(g)

The equation, CO(g) + ½ O2(g) CO2(g) would have an equilibrium constant with units

(lit/mole)1/2

.

2CO(g) + O2(g) 2CO2(g)

Initial conc.

2

1

= 0.5

2

1

= 0.5 0

Conc. at equilib. 0.5 x 0.5

2

x

x](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/chemicalequilibrium-240508121455-3fc1524e/75/Equilibrium-in-Physical-Processes-Class-11-Free-Study-Material-PDF-40-2048.jpg)

![All right copy reserved. No part of the material can be produced without prior permission

KC =

]

O

[

]

CO

[

]

CO

[

2

2

2

2

= 5 103

5 103

=

2

5

.

0

)

5

.

0

( 2

x

x

x2

Since, the value of equilibrium constant is pretty high so we can assume that almost entire CO goes

to CO2. Thus, value of x would be close to 0.5. But concentration of CO, (0.5 x) would not be

zero but would be a small value. Let this value be y. Then the concentration of O2 at equilibrium

would be

2

y

25

.

0 .

5 103

=

2

y

25

.

0

y

)

5

.

0

(

2

2

As value of y is very small,

2

y

can be easily ignored with respect to 0.25.

5 103

=

25

.

0

y

)

5

.

0

(

2

2

y = 1.4 102

[CO] = y = 1.4 102

M

Example 5:

In a study of the gaseous reaction,

A(g) + 2B(g) 2C(g) + D(g),

A and B are mixed in a reaction vessel kept at 25C. The initial concentration of B is 1.5

times the initial concentration of A. After the equilibrium has been established, the

equilibrium concentrations of A and D were equal. Calculate the equilibrium constant at

25C.

Solution:

Let the initial mole of A be 1, so the initial moles of B would be 1.5.

Let x moles of A reacted at equilibrium and ‘V’ be the total volume of the system.

A(g) + 2B(g) 2C(g) + D(g)

At equilibrium (1 – x) (1.5 – 2x) 2x x

At equilibrium, [A] = [D], 1 – x = x, 1 = 2x; x =

1

2

KC = 2

2

2

2

2

1

2

1

2

1

1

]

B

[

]

A

[

]

D

[

]

C

[

= 4

Example 6:

In a mixture of N2 and H2 in molar ratio of 1: 3 at 30 atm and 300°C, the percentage of

ammonia by volume under the equilibrium is 17.8. Calculate the equilibrium constant (Kp)

for the reaction,

N2(g) + 3H2(g) 2NH3(g)

Solution:

Let the initial number of moles of N2 and H2 be 1 and 3 respectively. (This assumption is valid as

Kp will not depend on the exact number of moles of N2 and H2, taken initially. One can start even

with x and 3x).](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/chemicalequilibrium-240508121455-3fc1524e/75/Equilibrium-in-Physical-Processes-Class-11-Free-Study-Material-PDF-41-2048.jpg)

![All right copy reserved. No part of the material can be produced without prior permission

Amount of ethanol at equilibrium = 46

3

1

1

= 30.67 g

Amount of ester at equilibrium = 88

3

1

1

= 117.33 g

And amount of water at equilibrium = 18

3

1

1

= 24 g

Example 9:

In a vessel, two equilibrium are simultaneously established at the same temperature

as follows,

N2(g) + 3H2(g) 2NH3(g) …..(1)

N2(g) + 2H2(g) N2H4(g) .….(2)

Initially the vessel contains N2 and H2 in the molar ratio of 9 : 13. The equilibrium pressure is

7P0, in which pressure due to ammonia is P0 and due to hydrogen is 2P0. Find the values of

equilibrium constants (KP’s) for both the reactions.

Solution

Let the initial pressure of N2 and H2 is 9P and 13P respectively.

N2(g) + 3H2(g) 2NH3(g)

9P – x – y 13P – 3x – 2y 2x

N2(g) + 2H2(g) N2H4(g)

9P – x – y 13P – 3x – 2y y

Pressure due to NH3 = 2x = P0

2

P0

x …..(i)

Pressure due to H2 = 13P 3x – 2y = 2P0

13P –

2

3

P0 – 2y = 2P0

13P – 2y =

2

7

P0 …..(ii)

Total pressure at equilibrium

9P x y + 13P 3x 2y + 2x + y = 7P0

9P

2

P0

+

2

P

2

P

7 0

0

= 7P0 [Putting the value from equation (i) and (ii)]

9P = 7P0

2

5

P0

9P =

2

9

P0

P =

2

P0