1) Metaphors, similes, and analogies help readers understand unfamiliar concepts by comparing them to familiar concepts. Metaphors state one thing is another, while similes state one thing is like another. Analogies argue the relationship between two things is so close understanding one illuminates the other.

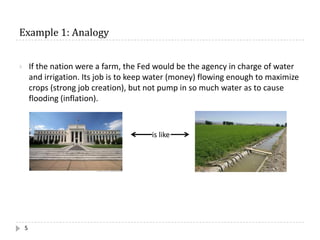

2) Examples show analogies used to explain the Federal Reserve and shell theory of the nucleus. Metaphors can also drive creative problem solving, as shown by Smeaton's use of ship and tree trunk metaphors in designing a lighthouse.

3) While metaphors facilitate understanding, they can also constrain thinking if they establish paradigms preventing other frames of reference.