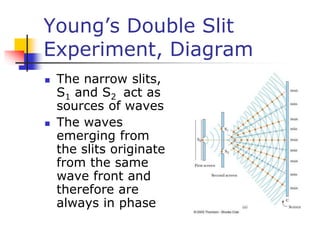

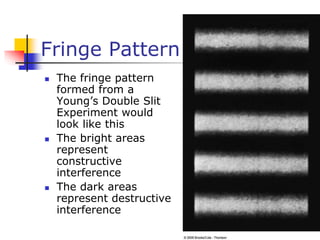

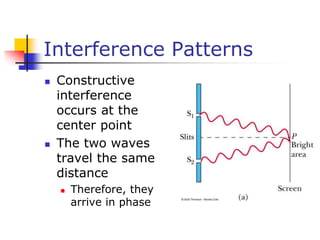

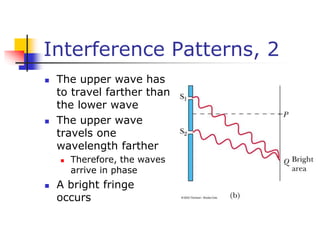

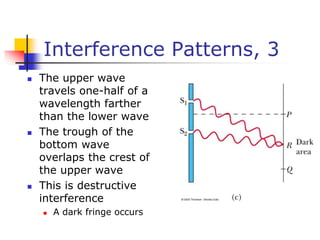

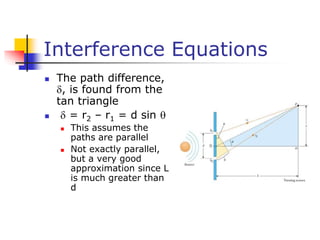

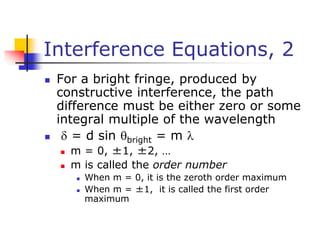

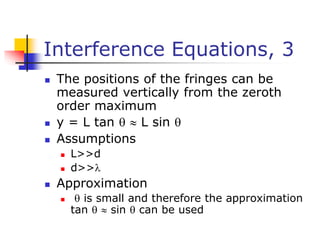

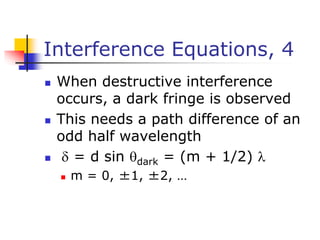

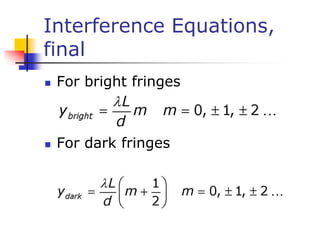

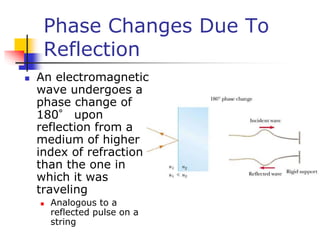

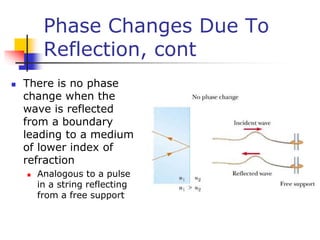

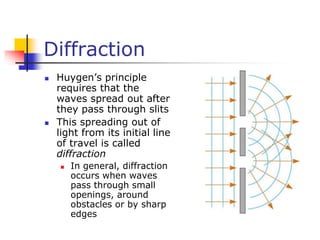

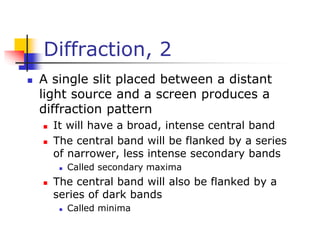

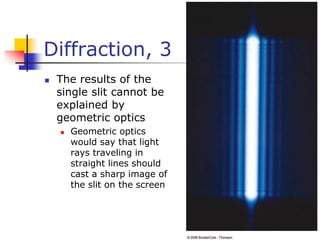

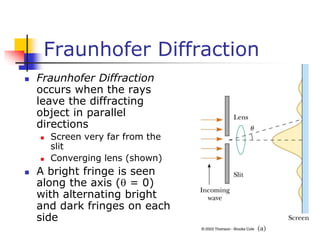

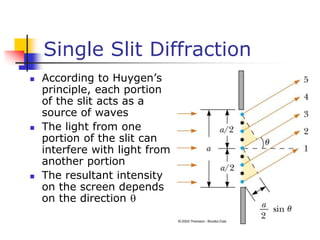

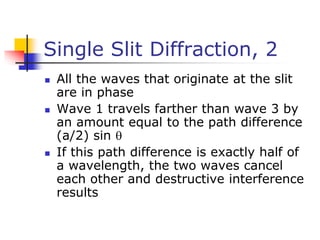

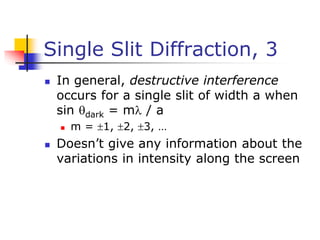

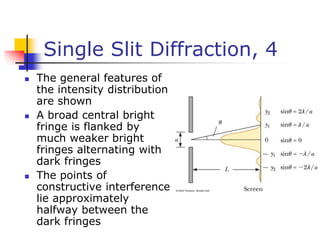

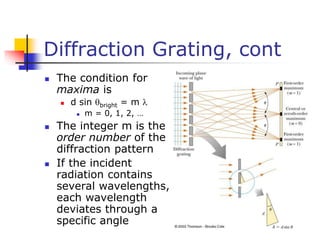

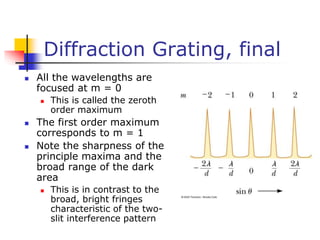

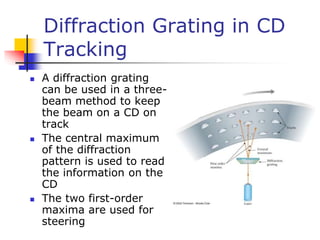

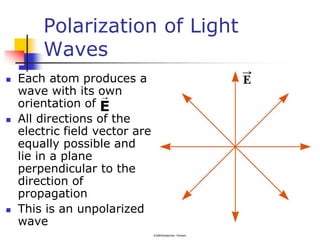

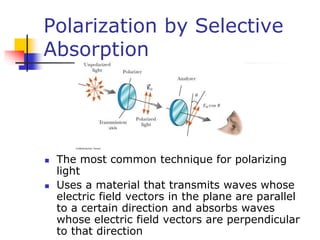

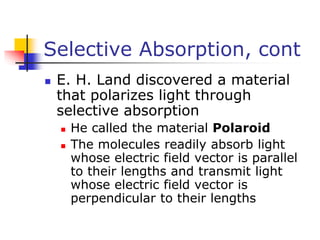

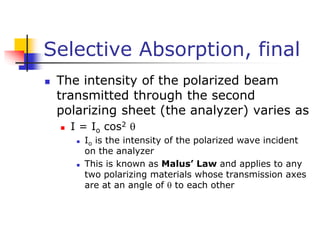

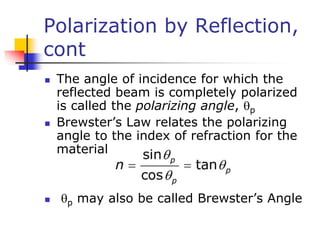

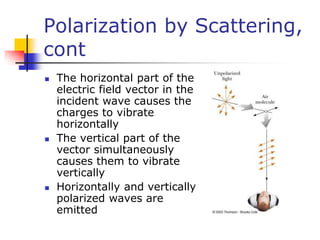

This document discusses key concepts in wave optics including interference, diffraction, polarization, and the wave nature of light. It summarizes Young's double slit experiment and how it demonstrated the wave nature of light by producing an interference pattern. It also discusses single slit diffraction, diffraction gratings, conditions for constructive and destructive interference, and how polarization occurs through selective absorption and reflection.