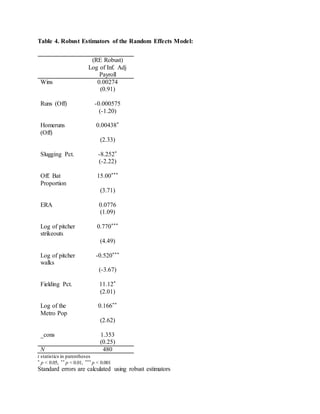

This document is a student paper that analyzes whether professional baseball team payrolls are linked to on-field performance. The student will create an econometric model using data on all 30 MLB teams from 2000-2015. Previous research has found mixed results on the relationship between market size and payroll. The student hypothesizes that controlling for market size is important. Descriptive statistics are provided on the key variables of logged and inflation-adjusted team payrolls and wins. The analysis will test whether factors like wins are correlated with higher payrolls.

![Work Cited

Averbukh, M., Brown, S., & Chase, B. (2015). Baseball Pay and Performance (PDF) [PDF].

Retrieved March 09, 2016, from https://ai.arizona.edu/sites/ai/files/MIS580/baseball.pdf

Hakes, J. K., & Turner, C. (2011). Pay, productivity and aging in Major League

Baseball. Journal of Productivity Analysis, 35(1), 61-74.

Hall, S., Szymanski, S., & Zimablist, A. (2002). Testing Causality between Team Performance

and Payroll. Journal of Sports Economics. Retrieved April 12, 2016, from

http://jse.sagepub.com/content/3/2/149.full.pdf html

Hoaglin, David C., and Paul F. Velleman. "A critical look at some analyses of major league

baseball salaries." The American Statistician 49.3 (1995): 277-285.

Tao, Y. L., Chuang, H. L., & Lin, E. S. (2015). Compensation and performance in Major League

Baseball: Evidence from salary dispersion and team performance. International Review

of Economics & Finance.

United States, U.S Census Bureau. (2010). Population Change for Metropolitan and

Micropolitan Statistical Areas in the United States and Puerto Rico: 2000 to 2010 (CPH-

T-2). DC.

United States, U.S Census Bureau. (2015). Annual Estimates of the Resident Population: April 1,

2010 to July 1, 2015 - United States – Metropolitan and Micropolitan Statistical Area;

and for Puerto Rico: 2015 Population Estimates. DC.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/02a0a1f3-94b4-40e8-b897-c891cc8f4202-160602131212/85/Econometrics-Paper-16-320.jpg)